Your webmaster has a history with the Manhattan Bridge — much more than the Brooklyn, as it turns out. As a kid I lived along the BMT 4th Avenue line, the R (local) and N (express) with the West End (then, the B) crashing the party at the 36th Street station, and (what was then) the D joining in at DeKalb. The N and, after 1967, the B and D all crossed the bridge into Manhattan. The Brooklyn Bridge, probably the most iconic and best-known of all NYC’s bridges, was largely a mystery to me — its mass transit lines, elevated trains and trolleys, had vacated it by the middle of the Fab Forties, and the only means of traversing it are by auto, bicycle and sneaker.

The first time I crossed the Brooklyn Bridge was in 1966, in a taxicab with the parents en route to the Port Authority Bus Terminal at 8th and West 41st to board a bus to Atlantic City (we either went to Atlantic City or a lake outside Troy, NY during the summer) and I do not really remember crossing it again until the mid-1980s when I would (very) occasionally bicycle from Bay Ridge to my nightshift job as a type speccer at Photo-Lettering and would use the Brooklyn Bridge, my only option at the time.

For decade after decade the Manhattan Bridge pedestrian walkways, on either side of the bridge outside the subway tracks, were not only out of commission but completely absent: the ribs of the superstructure were there but there was no walkway whatsoever: you’d look out the train window and see the East River where the walkway would be.

When the city finally completed about a decade of subway repair on the bridge, though, they deigned to rebuild the pedestrian walkways…

…and so for ForgottenTour 34 I decided to pay a visit to the Manhattan Bridge walkway, which remains something of a hidden treasure for many New Yorkers more familiar with the famed Brooklyn Bridge walkway — which was saved as a treat for the return trip. ForgottenTour 34 was delayed 2 weeks by the automatic rainstorm — rain has fallen on nine consecutive scheduled ForgottenTour days — but also in character, the makeup date (like the previous two, Tour #4 in St. George, Staten Island and our first Green-Wood Cemetery Tour #24, came out bright and sunny. (Most of the time; some drops fell when we got to Brooklyn).

Porte St-Denis, Rue St-Denis, Paris, France.photo: Adrian Smart

Above we see the Manhattan Bridge’s triumphal arch and colonnade… an attraction the Brooklyn, Williamsburg, Queensboro, and Triboro (soon to be RFK) Bridges lack. The Manhattan Bridge was constructed between 1901 and 1912 (it was proposed as far back as 1892) with Rudolph Modjeski and Othniel Foster Nichols as chief engineers and Leon Moiseiff as design engineer. [Steve Anderson recounts the details behind the bridge’s construction at nycroads.com.]

The grand Manhattan Bridge plaza, which fronts the Bowery at Canal Street, was completed in 1916 and is the design of John M. Carrere and Thomas Hastings, who also built the New York Public Library at 5th Avenue and 42nd Street. They looked to two classic European monuments for inspiration: The Porte St-Denis in Paris (the arch) and the Giovanni Bernini Colonnade at St. Peter’s Church in Vatican City.

The Porte St-Denis and Porte St-Martin in Paris are triumphal arches that celebrate military victories by “the Sun King”, Louis XIV (note the words ‘Ludovico Magno’ atop the arch). The St-Denis arch was completed in 1674 by sculptor Nicolas François Blondel. Bas-reliefs on the top and sides commemorate war campaigns and victories. Both arches greatly influenced the later Arc de Triomphe in Paris and the Manhattan Bridge arch, which as you can see is a close hommage.

The arch differs from the St-Denis arch in that it depicts two allegorical characters on either side of the roadway: the Spirit of Commerce on the north side, and the Spirit of Industry (above) on the south side. Both are the work of sculptor Carl Augustus Heber.

At the top of the arch is a frieze depicting Indians hunting buffalo by sculptor Charles Cary Rumsey, with a buffalo head at the keystone of the arch.

In some ways, the bridge’s sculptors present mixed metaphors. While Rumsey celebrated the Old West (odd, since the bridge points east), the Carrere and Hastings designdoes not allow us to forget the river the bridge crosses: what looks like the Creature of the Black Lagoon presides over a mix of seashells and conchs. Other sea-themed sculptures can be seen on the arch.

The soffit, or underside, of the arch is inlaid with 3 rows of carved rosettes.

For many years the Manhattan Bridge arch was poorly cared for and accumulated a patina of exhaust fumes and general soot. When it was finished in 1916 the auto was still in its infancy as far as a mass means of transportation and trolleys and horsecarts still traversed it; modern-day pedal-to-the-metal motorists cannot safely admire its plaza details, and it’s admittedly difficult for pedestrians to get at it. Thankfully the city power-washed the arch and colonnade a few years ago, and rebuilt the plaza. It’ll never be a place for quiet reflection ever again, but it is again the plaza the Manhattan Bridge, which celebrates its centennial (along with the Lincoln Penny) in 2009, deserves.

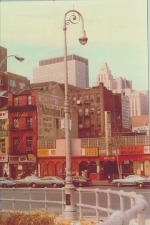

Before we set out across the bridge, let’s look back for a second at the domed 1924 Citizen’s Bank at Bowery and Canal (now one of the ubiquitous Hong Kong-based HSBC branches) and a great telephoto shot by ForgottenFan Tim Skoldberg that captures the verve and pace of Chinatown in 2008. The Manhattan Bridge, arriving at Bowery and Canal Street from Brooklyn, is the main gateway to Chinatown.

The three large suspension bridges spanning Brooklyn and Manhattan are unusual in that none directly connect to major superhighways, though the Brooklyn Bridge contains ramps to the FDR Drive and BQE. As we’ll see below, though, there were plans in that vein for the Manhattan that were thwarted by the citizens of Manhattan.

Before we set out across the bridge, let’s look back for a second at the domed 1924 Citizen’s Bank at Bowery and Canal (now one of the ubiquitous Hong Kong-based HSBC branches) and a great telephoto shot by ForgottenFan Tim Skoldberg that captures the verve and pace of Chinatown in 2008. The Manhattan Bridge, arriving at Bowery and Canal Street from Brooklyn, is the main gateway to Chinatown.

Before we set out across the bridge, let’s look back for a second at the domed 1924 Citizen’s Bank at Bowery and Canal (now one of the ubiquitous Hong Kong-based HSBC branches) and a great telephoto shot by ForgottenFan Tim Skoldberg that captures the verve and pace of Chinatown in 2008. The Manhattan Bridge, arriving at Bowery and Canal Street from Brooklyn, is the main gateway to Chinatown.

The three large suspension bridges spanning Brooklyn and Manhattan are unusual in that none directly connect to major superhighways, though the Brooklyn Bridge contains ramps to the FDR Drive and BQE. As we’ll see below, though, there were plans in that vein for the Manhattan that were thwarted by the citizens of Manhattan.

Lamppost Graveyard

Clockwise from top left:Decorative stanchion in arch holding 1930s “gumball” luminaire; 1950s curved-mast octagonal post with Westinghouse AK-10 “cuplight” luminaire; “Type F” post holding gumball; “crescent moon” unit on original Manhattan Bridge walkway mast; Type 24 A-W Bishops Crook post, Bowery at bridge entrance, 1978

Prior to the plaza’s late 1990s-early 2000s renovation, not only was the arch and colonnade left to the ravages of pollution in traffic, but neglect by the Department of Transportation left the Manhattan Bridge traffic entrance a repository of decades-old lamppost styles, most still fitted with incandescent bulbs. These fossils were all swept away a few years ago, but the bridge is still recalled as the La Brea Tar Pits of NYC lampposts.

The tour was forced to use the northern pedestrian walkway due to filming on the southern walkway for the remake of the 70s subway thriller The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3. The southern walkway is perhaps the preferred once since it features a view of the nearby Brooklyn Bridge, lower Manhattan and the Statue of Liberty.

The massive bridge anchorages are hidden from exterior view by four massive granite colonnades featuring Doric columns. On street level, Cherry Street on the Lower East Side and Water Street in DUMBO pass under the anchorages, though the Water Street passage is closed off at present. Sidewalks, too, pass under arches such as on Adams Street (left).

There is an iron superstructure that covers the middle roadway for a distance on the Manhattan side. While it is purposeless now, it was constructed in the early 1960s as part of the city’s effort (spearheaded by Robert Moses) to build Interstate 478 across the bridge, then north along Chrystie Street, west along Broome and then connecting with the Holland Tunnel to New Jersey. After years of lawsuits and opposition to the building of what was dubbed “LoMex”, the Lower Manhattan Expressway, the expressway was finally cancelled in 1969.

When the Manhattan Bridge walkways were reopened in mid-2001 (south side) and 2004 (north side) some aficinados questioned the inclusion of tall chain link fences in front of the rail proper. 1930s photos by Berenice Abbott show that they weren’t there during the walkways’ first incarnation.

Came the news that one day after our Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridge jaunts, a distraught 35-year-old woman plunged into the East River from the Brooklyn Bridge (whose walkway is accessible to the water via an arduous climb across the metal spans covering the roadway). You just know folks would be easily leaping over a fence as low as this one.

no images were found

East Broadway (left) and the FDR Drive, as seen from the north Manhattan Bridge walkway.

The Manhattan Bridge was built as architecture was beginning to move past Beaux-Arts into more utilitarian modes. But the bridge still has several intriguing decorative elements that can be seen at the two towers (which are supported by two columns apiece). A large plaque listing the bridge builders and NYC officials during construction can be found on the Manhattan tower on the north walkway.

The Manhattan Bridge employs 21-inch steel cable, the strongest of all East River bridges. Original plans called for it to be a parallel wire suspension cable bridge, then an eyebar/chain bridge before returning to the original plan.

Manhattan Bridge firsts: the first bridge to employ flexible steel towers; first to use a Warren stiffening truss; and first to employ two suspender ropes straddled over the main cables to attach to the floor beams.

The twin roadways on either side of the bridge atop the subway lines were originally used by trolley lines. Trolley service over the bridge ceased in 1929, and the lanes were then taken over by cars.

Subway service on the Manhattan Bridge began in 1915. Originally the Sea Beach Line (today’s N) traversed the bridge on the north set of tracks, with the south side connecting the BMT 4th Avenue line with the Chambers Street station on the Nassau Street line.

In 1967 the track connections over the bridge at both ends were drastically rearranged and altered. As a result, the little-used connection with the Nassau Street line was severed, with the Sea Beach taking over the south end of the bridge and the Brighton Line gaining a new connection to Manhattan. In the 1980s and 1990s, the wages of both placing the subway tracks on the outside edges of the bridge’s undersides resulted in the discovery of major damage to bridge supports. Subway cars, as they cross the bridge, cause the structure to twist slightly, with dire results as the decades passed. The fact that the tracks on the northern end got much more use than the ones on the south end was also a factor in the torsion. To repair the bridge it was necessary to shut down subway service on the south tracks, then the north, for most of the 1990s. Service was restored to full capacity in 2004. (When service on the Broadway Line was stopped in the aftermath of 9/11/01, the J line stepped into the breach, thanks to a connection made with the Broadway Line via the Montague Street tunnel in the 1930s; J trains ran to Bay Ridge for a few weeks in the fall of 2001!) Here are some terrific photos of Manhattan Bridge subway service in nycsubway.org.

Left: detail at tower, showing lighting that lines the “hoods” protecting the walkways from any debris coming from the towers.

At this point in the tour, New York City tour guide, writer, traveler and “guerilla urbanist” Moses Gates described a trip he made scaling the Manhattan Bridge tower. Bridge photographer Dave Frieder has also accomplished the feat. ForgottenFan Steve Duncan, like Gates a guerrilla urban explorer, was also on hand.

Nearing the Brooklyn end (connecting with Jay Street on the south side, Sands on the north) we see some of the new buildings of Dumbo (the former industrial wasteland is quickly becoming a high-rise haven) and the Jehovah’s Witnesses Watchtower Building. The Witnesses, a religious fellowship that sprung from the teachings of evangelist Charles Taze Russell, believe Jesus Christ is God’s (Jehovah’s) son, but consider him separate and not equal to God. The organization owns dozens of properties in Brooklyn Heights, including the massive yellow Watchtower Building shown here.

Making our way toward the Brooklyn Bridge, we spotted a pair of superannuated anomalies — on Tillary Street and Adams, a 1950s-era round Brooklyn Battery Tunnel marker (pointing toward the southbound BQE, which connects to it). This sign must be meant for truckers, since the Brooklyn Bridge, closed to trucks, is the closest Brooklyn-Manhattan crossing. On the BQE Brooklyn Bridge connecting ramps is a flock of 1930s-era Type 41 posts. They were originally fitted with ‘gumball’ lumes and were first employed on the Whitestone Bridge. Look at all the signs! I count nine in the foreground and 3 more on the post in the background.

S. Parkes Cadman Plaza. This 10-acre park between Johnson and Prospect Streets and Cadman Plazas East and West (Washington and Fulton Streets) replaced several square blocks of densely populated downtown Brooklyn in the 1940s. It is surrounded by federal and state courts and the former main branch of the Brooklyn Post Office (since moved to far estern Brooklyn near Starrett City) and the offices of the International Red cross. It was named for influential Brooklyn Congregational radio preacher Samuel Parkes Cadman (1864-1936). He nicknamed the Woolworth Building the “Cathedral of Commerce.”

Your webmaster never saw the streets Cadman Plaza replaced, but I’ve always been put off by the stillness and sterility of the place, which our next attraction does nothing to dispel…

Brooklyn’s massive, austere World War II Memorial stands inside Cadman Plaza north of Clark Street.

The memorial (dedicated in 1951) was designed by Stuart Constable, Gilmore D. Clarke, and W. Earle Andrews, who worked in concert with the architectural firm of Eggers and Higgins. The two larger-than-life sized high relief figures by sculptor Charles Keck (1875-1951) depict a male warrior on the left and a female with a child to the right, and serve as symbols of victory and family.

FNY’s reigning King of Lampposts, Bob Mulero, pointed out Type B posts (left), which can be found by the thousands in NYC parks, and the rarer Type E posts (right) which have lengthier shafts and extra scrollwork.

A short detour to Henry and Middagh Streets gave us new looks at painted building ads I first saw during FNY’s early days in 1998-1999:

A very large painted ad on the corner of Henry and Middagh Streets proclaims Peaks Mason Mints, and is the former home of the Mason, Au and Magenheimer Candy Company. According to advertisement researcher Walter Grutchfield, the company was in business here between 1892 and 1949 and was founded by confectioners Joseph Mason and Ernest von Au in 1864.

In actuality the sign is a bit misleading since there was no such candy as “Peaks Mason Mints” there were Mason Peaks and Mason Mints. Mason Peaks was a coconut-chocolate combination (like Mounds) while Mason Mints was a chocolate-covered mint patty (like today’s Peppermint Pattie). Mason also made Dots, a fruit or cinnamon-flavored gumdrop, and Crows, a licorice-flavored gumdrop. Both are still distributed by Tootsie Roll, which acquired Mason in 1972.

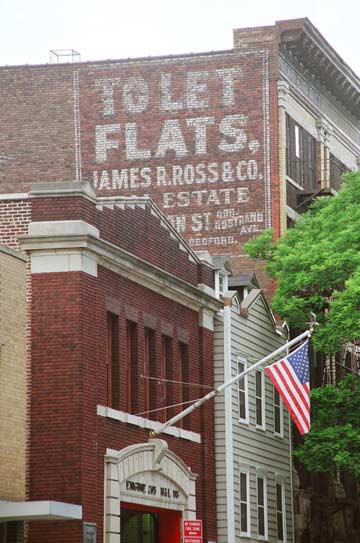

Note the painted ad across Middagh Street from the Peaks Mason sign: it reads “To Let: Flats, James R. Ross & Co. Real Estate.” Its age is revealed in its usage: We haven’t called apartments ‘flats’ in the USA (as they still are in Britain) for several decades; today, the ad would probably read, “Apartments for Rent.”

Cadman Plaza West and our next target, the Brooklyn Bridge. Once CPW gets past the Brooklyn Bridge approach ramps, its moniker changes to Old Fulton Street; it was once contiguous with Fulton Street, which today runs from Adams Street east to the Queens line at Eldert Lane. It was once an Indian trail, then the northern branch of Kings Highway (see this FNY page for more).

Washington Street at the pedestrian entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge, looking north to the Manhattan. Here’s a DUMBO Easter egg for you: walk north along Washington to about Water, then look through the twin tower bridge colums. The Empire State Building will be exactly between the columns.

The Telectroscope (which to your webmaster resembles a large, um, er…) well, it’s a device which, using broadband satellite technology, enables people on either side of the Atlantic Ocean to see each other and even communicate via cellphone and well, hand gestures. It was placed on Old Fulton Street and in London, England by British artist Paul St. George. The Telectroscope was available in both Brooklyn and London between May 22 and June 15, 2008.

The Brooklyn Bridge, constructed between 1870 and 1883 by John Roebling (who perished from tetanus during the construction) and his son, Washington Roebling (who suffered from the bends and supervised construction from his home in Brooklyn Heights, relaying commands via his wife) is perhaps the most storied and most famous bridge in the world. I won’t recount the details of its construction here — I’ll let Steve Anderson do it in NYCRoads; Ken Burns on PBS, or David McCullough in The Great Bridge.

I’ll instead fall back on Forgotten aspects of the Great Bridge and note that the bridge’s distinctive diagonal cables don’t show up on the plaques of the subway station nearest the bridge, the BMT Chambers Street station, probably as a nod to deadlines or expenses.

I can’t say with certainty if the original lightposts on the Brooklyn Bridge resembled the present ones. The current design harkens back to the gaslight era, with footrests for snuffing or lighting gas fixtures. If the original Brooklyn Bridge, finished just as the Edisonian era was dawning, had walkway lamps at all, they were most likely gaslamps. The present stanchions replaced the previous generation in 1982; those lamps were lit by ‘gumball’ lumes lit by incandescent bulbs. They closely resembled the present ones, but with “busier” molding at their bases.

Concluding with a look at the King of All Buildings from the bridge, a look back at Brooklyn, and a greeting from photographer Tim Skoldberg, a former teammate at the World’s Biggest Store. We wound up the proceedings with a few highlights in City Hall Park, inclusing a look at Nathan Hale’s statue from afar. Patriot Hale, when the sculpture was dedicated decaces ago, was thought to have been hanged by the British in the vicinity of what is now City Hall Park; modern scholarship has him killed near where the United Nations is, in the East 40s near the East river.

On a personal note, I was reunited with two cousins at tour’s end, John Cornejo (from Los Angeles) and Moya Whelan (from Vancouver, BC) whom I hadn’t seen since 1988. It was an emotional scene.

Photos, except where noted: Joe DeMarco, Bob Mulero, Tim Skoldberg.