With little warning or fanfare, the MTA is about to shutter one of its most venerable stations to passenger traffic in just a couple weeks [as of December 2008], the South Ferry terminal, as it prepares to open a state of the art terminal with straight platforms, a center island, and a transfer to the nearby N/R BMT line, enabling riders to proceed on to Brooklyn, or uptown via Trinity Place and Broadway. The new terminal will also permit full trainsets to admit and discharge passengers, which the older South Ferry terminal was unable to do, and will cut down somewhat on noise pollution: the curved tracks made South Ferry one of the system’s “screechiest” stations, and at Chambers Street, the motorman was obliged to loudly and repeatedly announce that anyone wishing to detrain at South Ferry has to move up to the first five cars.

While not one of the Original 28 NYC subway stations (from City Hall to 145th Street) that opened in 1904, South Ferry opened the very next year and boasts architectural and design elements that closely match the ones in those stations, decor by the architectsGeorge L. Heins and Christopher G. LaFarge, who also designed the Cathedral of St. John the Devine and the original buildings in the Bronx Zoo.

After the Original 28 opened on October 27, 1904, the city’s subway engineer William Barclay Parsons, did not rest. Already planned were numerous extensions to the original zigzag route. The South Ferry, Bowling Green, Wall and Fulton Street stations opened downtown in 1905, as southern extensions of the original trunk line. 157th through 242nd on today’s #1 line were finished by 1908 and the IRT was already pushing through to Brooklyn by that time. Subway construction that swift would be impossible today for a variety of reasons — improved safety and work conditions, to name just two.

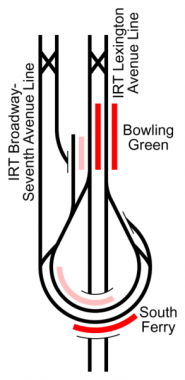

Today, South Ferry is the southern limit of the 7th Avenue line (the #1 train), but this was not always the case: it was originally built for the IRT Lexington Avenue line (today’s #4 and #5 trains), with outer platform and inner loop track: express trains used the South Ferry loop, while locals used the City Hall loop. The 7th Avenue Line, today’s #1, was extended south to South Ferry in 1918 and took over the outer loop platform, with the Lex trains that terminated at South Ferry using the inner.

Today, South Ferry is the southern limit of the 7th Avenue line (the #1 train), but this was not always the case: it was originally built for the IRT Lexington Avenue line (today’s #4 and #5 trains), with outer platform and inner loop track: express trains used the South Ferry loop, while locals used the City Hall loop. The 7th Avenue Line, today’s #1, was extended south to South Ferry in 1918 and took over the outer loop platform, with the Lex trains that terminated at South Ferry using the inner.

The use of the inner loop has been a little complicated over the years.NYCSubway.org:

Essentially a separate station, the South Ferry inner loop platform was built in 1918 for IRT Lexington service when the IRT West Side service was given the outer loop. The inner loop platform was used up till 1977, mostly by a shuttle to the Bowling Green station on the Lexington/Brooklyn IRT. Because of the sharp curve (even sharper than the outer loop), trains could open only their center doors at the inner loop station, and so instead of a full platform face, slightly arched openings were cut into the old walls only where the center doors would be. This also probably simplified the engineering problem compared to removing all of the old wall. Starting in the late 1950s, when the new R-type cars displaced most of the original IRT rolling stock, trains arriving from the Lexington line on nights and weekends were rerouted to share the outer loop, because on the new cars it was not possible to selectively open only the center doors. The weekday shuttle used specially modified cars that opened only center doors, and continued using the inner loop until service ended in 1977. The track past the inner loop is still used to turn the #5 train when it is terminating at Bowling Green and not running to Brooklyn. The inner loop platform at South Ferry is now used for crew quarters, offices, storage, etc. and has a separate entrance from the fare zone upstairs. There was no free transfer between trains on the two platforms.

That NYCSubway page also has some top-secret pictures of the inner loop and its passageways. Map: wikipedia. Closed platform areas are shown in pink.

Joe Brennan tells the whole complicated story of the Bowling Green and South Ferry interchange. The track system today allows 7th Avenue and Lexington Avenue trains to enter each others’ routes, though this is done only when trackwork closes some stations and forces reroutes.

These pictures pretty much show the entire length of the South Ferry platform, which only allows five cars to open. Before the 1950s, regular trainsets on the IRT Seventh Avenue were short and this wasn’t a logistical mess, but after that, the longer 10-car trainsets presented a problem. For several decades, the solution has been to allow just the first five cars to platform.

The South Ferry station on the IRT is the subways’ only “rails to sails” transfer point, as service on the Staten Island Ferry is available on the surface. A brand new ferry terminal was opened in February 2005 (after the previous one had burned down in the late 1980s and the city had used a couple of temporary terminals) and the 1951 terminal on the Staten Island side was renovated from top to bottom, with work completed the following year. Ferry service has been free of charge for several years, but with the severe money crunch of the late 2000s, your webmaster wouldn’t be surprised if a fare is in the offing, though I’ve not heard anything regarding that yet.

Early Heins & LaFarge subway stations featured oak ticket booths and oak-cased clocks produced by the Self-Winding Clock Company of New York. There weren’t any tokens or turnstiles in the beginning — you bought a ticket at the booth and presented it to a ticket taker at the gate, who would drop it into an oblong ticket chopper, which at the turn of the crank would chop it into pieces. Believe it or not, I would still see the odd ticket chopper at a couple of stations in the 1980s — I hope they found a home in the MTA Transit Museum.

The ticket booths and choppers may have vanished long ago but Beaux Arts flourishes can stil be found on the station ceiling. The squares once held incandescent bulbs in the center. A few of them stil support light fixtures. Also note the intertwined figure 8 design.

Because the South Ferry station is looped the curves are pitched very steeply. Subway cars, of course, are not curved, and so there are large gaps between the platform and the cars. Gap fillers, or movable platform extensions, are used for safe egress and entrance. The use of gap fillers was necessitated by the IRT’s conversion to cars containing a middle door around 1940; prior to that, the doors on either end of the cars were sufficiently close to the platform to not need them. When the old South Fery station closes, however, gap fillers will still be used at the IRT Lexington line Union Square station downtown platforms and the Times Square shuttle tracks 1 and 3, both of them Original 28 stations. The Brooklyn Bridge uptown and downtown express platforms have been deactivated but can still be seen south of the present platforms.

Forgotten Fan Walter Kehoe: In the days before the automatic platform extenders, there was at least one foreman and probably two or more who had direct line of site with each other. After the train was stopped at the station each of them gave a signal to one or two men that operated a large, about 4-5 foot tall wooden lever that he pulled towards himself to extend the platform to the train he then signaled the other foreman and a whistle was blown and the conductor opened all the doors to the platform. You could open all the doors when they were manually extended as the operator had complete control of the extension. After the doors on the train were closed a signal was given to the operators and the extender lever was pushed by the operator away from himself and the extender was retracted. Then a whistle was blown, signalling to the engineer that all was clear and he then moved the train out of the station.

Here’s a video your webmaster took of the South Ferry gap filler in action. I do not imagine I will be clutching a goldplated stauette at the Kodak Theatre in Hollywood anytime soon.

Note the “screechiness” of the station, and the NYC method of entering the train before the people already on have gotten off.

Original Heins & LaFarge station nameplates are subtly intricate, with pink outerborders, a green inner border with checkerboard, vine and bellflower detail, and finally the brown background with white sanserif letters, all done with hundreds of mosaic pieces. Note that though the letters are sanserif (stations done from 1915 on would use serifed lettering) the R’s still have a little flourish on the end, a design element they didn’t have to include, they just did. The walls have white tiles with brown molding at the top and marblization at the bottom.

Two Unimark-style signs at South Ferry. Unimark was an international design consultancy headed by designers Massimo Vignelli and Ralph Eckerstrom charged with the standardization of subway signage in NYC, and Vignelli’s vision, which included a extraordinarily stylized subway route map, began to take hold in the system in the late 1960s. Subway signs were originally white with black type in the Akzidenz/Standard type font, but gradually evolved to black signs with white Helvetica type for better readability.

Paul Shaw has written the definitive history of NYC subway signage for AIGA, the international design association.

The pieces de resistance of the South Ferry terminal are the fifteen ceramic plaques depicting a sloop in the harbor. Heins and LaFarge were in the habit of depicting historic or symbolic scenes on station artwork; for example, Astor Place depicts a beaver because John Jacob Astor made his millions in the beaver fur trade; Wall Street, the actual wall the Dutch erected on the site of present-day Wall Street to keep out Indians and British. When Squire Vickers took over subway design in the 1910s, he continued the tradition for awhile, but using tilework instead of ceramics.

Ceramic plaques of this type were manufactured by either the Grueby Faience Company or Rookwood Pottery. It is likely the latter was the case here. South Ferry is one of three stations that received festooned garlands and station monograms, the other two being Fulton and Wall Streets on the Lexington Avenue line.

The city, more specifically the Department of Transportation, has not done right by these plaques, however. Originally they were in brilliant, vivid color — the water was green, the sky blue and the billowing cumulus clouds white. At some time in the past, someone thought they would look better with an overlay of either gold leaf or brown paint. Or is that simple grime and track dust? In any case, they aren’t what they used to be. Hopefully the Transit Museum will move one or two and restore the plaque to its old-time majesty and display it proudly.

Monogram letterplate and paneling. Once again, only three stations in the whole system were bestowed by Heins and LaFarge with this design element. Above: ceramic paneling at the roofline. Some stations got poppies; some, tulips; check the full view of the plaque, above, to see what South Ferry got.

Heins and LaFarge stations are often full of angles and corners. The stairs are divided into two — the one you take is determined by whether you want to sit in the front car or further back, though with the five cars that are accessible, it doesn’t make much difference. Your webmaster usually enters the 5th car and I then walk back as far as I can since I usually exit at Penn Station and the exit is toward the back of the platform. With the R-62 trainsets, though, you can’t walk back all the way because there’s a locked door midway through the train. I exit at Rector and hustle on the platform to the next car and then walk back a few more cars.

The mural found on the staircase landing, South Sails, is by Sandra Bloodworth, presently [2008] the director of the Arts For Transit program. It is a rendering in tile of the Heins and LaFarge plaque, matching it color for color. One of the earlier examples of new art in the subways, it was installed in 1990. Sandra Bloodworth co-authored Along The Way, a compendium of subway artwork (Monacelli, 2006)

The border molding, which continues at the roofline on the staircases, repeats the ceramic molding, monogram, and poppy motif. I don’t know what will become of this piece when the new terminal opens.

Station entrance and fare control area, new ferry terminal. I am not sure if the new platform will be accessed from inside the terminal or not.

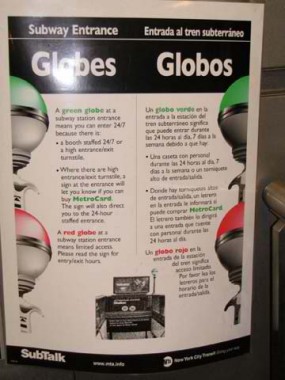

LEFT: explanation of the “globe system” the MTA has for passengers to determine whether a station can be entered. Basically if a station is green, you’re good, but red is only open part of the time. An older scheme (which was somewhat better) had globes fully illuminated in red, green or yellow, with green open all the time, yellow open some of the time, and red exit-only.

LEFT: explanation of the “globe system” the MTA has for passengers to determine whether a station can be entered. Basically if a station is green, you’re good, but red is only open part of the time. An older scheme (which was somewhat better) had globes fully illuminated in red, green or yellow, with green open all the time, yellow open some of the time, and red exit-only.

So, so long to the South Ferry station. When the renovation was first announced a few years ago I thought it would entail a platform extension and a new tunnel allowing a BMT transfer, and the frequent closings and reroutings didn’t dissuade me from that. I should have known, though that the MTA wouldn’t have extended a loop platform which would have been quite difficult to do. We’ll get, therefore, the first new station to open since 1989, when the three stations linking the 6th Avenue line to the Queens Boulevard line were opened.

And, there will be no more architectural extravaganzas like the ones Heins and LaFarge designed. The new station is white and chrome, like an Apple iPod store.

Photographed December 18, 2008; page completed December 21