Hunt’s Point in the Bronx, an enclave relatively cut off from Longwood by the Amtrak railroad cut and Bruckner Expressway, is where auto glass, auto parts, light industry and manufacturing are carrying on without pressure from the city. It also brought FNY a much-needed Bronx tour, a borough that has been somewhat neglected lately by the FNY camera — it’s not readily reachable from Little Neck without a couple changes of trains. Your webmaster will try to alleviate the Bronx dearth as I carry on.

Hunt’s Point, not to be confused with Queens’ Hunters Point, is easily definable as it is cut off fron the rest of the Bronx by pedal-to-the metal Bruckner Expressway, the East River, and the Bronx River, which divides it from Soundview and Harding Park. It was settled as early as the 1690s by the Leggett and Hunt colonial families, and for many years it was a rural enclave dotted with opulent mansions owned by Edward Faille, Paul Spofford, Cuban patriot Innocencio Casanova and Benjamin Whitlock. The only trace of them now, and other colonial-era names, are words on street signs…

In the early 20th Century, the coming of high-speed railroad lines, as well as the elevated and subway lines, spelled the conclusion of Hunt’s Point’s rural era of exclusivity. Single-family homes and apartment buildings arose along streets in the northern half of the neighborhood, with industry and railyards along the East River to the south. Two of the largest produce markets in the world, the New York City Produce and Meat Markets, opened in 1967 and 1974 respectively. The old Fulton Fish Market joined them in 2007. They are now surrounded by the Hunt’s Point Industrial Park, hosting over 800 businesses and a large Con Ed plant at the southeast end of the neighborhood at East Bay Avenue.

Like the rest of the Bronx, Hunt’s Point suffered a severe decline in the 1970s and 1980s as poverty, crime, arson and a crack cocaine epidemic caused severe privations. The area lost close to two-thirds of its population by 1985. Hunt’s Point continues to struggle out of this malaise as best it can. The opening of the new Barretto Point Park (see below) is a sign of hope.

Wayfaring: HUNT’S POINT

After getting off the #6 Lexington Avenue local at Longwood Avenue, a block’s walk takes you to the barrier: Bruckner Boulevard and Expressway, and a formidable one it is. It was once a simple two-lane road called Whitlock Avenue; gradual expansion through the years has produced first a surface multi-lane roadway called Eastern Boulevard, renamed (1942) Bruckner Boulevard for a Bronx borough president (1918-1933) Henry Bruckner. Transit czar Robert Moses placed a new Bruckner Expressway on the drawing board in 1951. So it was written, and so it shall be done… and the heavily-trafficked expressway was constructed, in Hunt’s Point, along the railroad between 1956 and 1961.

The Bronx has its share of historic bridges, and there are some very old ones that take various roads over the Amtrak tracks into Hunt’s Point. One such is the 1906 through truss Lafayette Avenue Bridge, shown here.

We’ll touch on the Bronx street plan on this page — it’s rather weird in spots, and quirky in others. Lafayette Avenue begins at the Bruckner and proceeds in fits and starts through four neighborhoods all the way to Eastchester Bay (accompanied by the parallelling Randall Avenue). It is interrupted by the Bronx River and Westchester Creek along the way, but, undaunted, reaches its eventual destination.

The Badabing strip club is the first address you see in Hunt’s Point after crossing the bridge; apparently Tony Soprano has set up his Bronx operations here.

Show Me The Money

From the ForgottenBook: This fortress-like building at Lafayette Avenue and Tiffany Street has produced Mexican, Brazilian, Costa Rican, Ecuadorian and Haitian stock certificates, travelers’ checks and stock certificates, as well as paper money. The company later to become American Bank Note was founded in the 1790s by engraver Joseph Perkins, a Massachusetts native from Newburyport; the company was incorporated in 1858. American Bank Note did produce US currency from 1858 to 1879, and for a short time in 1861 produced Confederate money. The company also entered into printing stock and bond certificates in association with the New York Stock Exchange in the later 19th Century. Its Bronx factory was built in 1911 and it was designated as a NYC Landmark in 2008.

Later, the American Bank Note Building was home to artists’ studios and Wildcat High School, established for troubled students by the Wildcat Service Organization. Developed in 1972 by Mayor John Lindsay as a “program of last resort” for the chronically unemployed, the organization provides job skills and training for the economically disadvantaged. It is also being refurbished and new apartments and new retail constructed.

By 2012 it had gone the luxury condo route, as The Banknote.

For many years the ABNC employed an engraver named Joseph Ford, who was a legal counterfeiter! He duplicated various currencies produced here; his successes in counterfeiting banknotes prompted changes in their manufacture. His son, William, became the world’s most successful portrait engraver (the type that appear in the Wall Street Journal).

Directly across Lafayette Avenue from the Bank Note building is Corpus Christi Monastery, home to a flock of cloistered Dominican nuns. It is thickly walled on its Tiffany and Manida Streets and Spofford Avenue sides; it was designed in 1890 by architect William Schickel.

Gilbert Place, between Hunts Point Avenue and Faile Street north of Lafayette, was named for late 1800s area magnate W.W. Gilbert, the owner of Sunnyslope (see below). The one-block place contains homes typical to the Bronx: attached houses with bowed front rooms. However, noncontextual development, or Bronx crap, is starting to move in.

More of the same general plan on nearby Irvine Street, between Seneca and Garrison Avenues east of Hunts Point Avenue. 899 and 901 have particularly aged doorways.

Hunts Point and Garrison Avenues. Hunt’s Point is the auto glass capital of NYC with dozens of competing shops in the neighborhood.

Long Gone

The Hunts Point railroad station is a relic of a period when local service was offered on high-speed rail lines in the southern and eastern Bronx, and additionally a relic of the days when grand buildings were constructed even on local stops in areas that were not necessarily in the center city. This station served the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad (Amtrak tracks still run underneath Hunts Point Avenue here). It as designed by Cass Gilbert — the architect of the Woolworth Building — in 1908. This is one of a series of deteriorating rail stations in the Bronx along the old NY, NH & H.

The station is home to a variety of businesses; lawyers, travel agencies, pizza, fried chicken, groceries, topless. The “Welcome to Hunt’s Point” sign is a few years old and is on an adjoining building.

Sunnyslope

Many Hunt’s Pointers are unaware that they have a pair of landmarked buildings in their midst — the aforementioned American Bank Note building and the Bright Temple African Methodist Episcopal Church at Lafayette Avenue and Faile Street. It was constructed in the 1860s on the Peter Hoe estate, when Hunt’s Point was part of the town of West Farms in the county of Westchester. According to Barbaralee Diamonstein’sLandmarks of New York, the building was designed in the Picturesque Gothic tradition, and resembles several of the homes mentioned in Calvert Vaux’ Villas and Cottages, though there is no known connection between Sunnyslope, as the building was named, and the co-architect of Central and Prospect Parks. The Hoe family business was printing; Peter’s brother, Colonel Richard Hoe, invented the rotary printing press.

After Hoe sold the estate in 1864, Sunnyslope passed through many hands, in 1919 becoming the Temple Beth Elohim. It has been owned and occupied since 1966 by the Bright Temple AME.

It is one of the very few of the country houses from wealthy estates still standing in the five boroughs.

Hunts Point Avenue is the main north-south artery in the neighborhood. In the early 20th Century it replaced the older Hunts Point Road, which made a rather more winding and circuitous route in the peninsula. Hunts Point Avenue runs from Cramer Square at Southern Boulevard and East 163rd Street southeast to East Bay Avenue and Halleck Street, with East Bay Avenue the main road to the Produce markets.

Bryant Avenue is rather nondescript in Hunt’s Point, but I’m using the photos to illustrate an unusual street naming pattern. Because of the presence of the last resting place of poet Joseph Rodman Drake (see below) city planners decided to name other streets in the area for 19th Century literary superstars. Hence, William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier,Drake, and Fitz-Greene Halleck are remembered here, and maps from the 19th Century show a Payne Street (for John Howard Payne, “Home, Sweet Home”), Bacon Street (for Sir Francis Bacon), Falconer Street (for Scottish poet William Falconer) and Poe Avenue as well. The now-demolished streets were replaced by the Hunt’s Point produce markets.

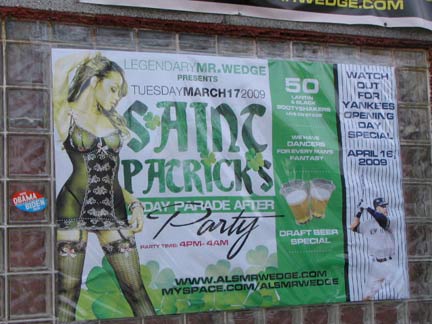

Another of Hunt’s Points strip clubs at the wedge formed by Hunts Point and Bryant Avenues is ready to celebrate March 17th.

At Hunts Point and Randall Avenues, I saw the first Mr. Softee truck of the season (March 14). Many of the trucks, from different companies, have their home bases in Hunt’s Point. On the Deland warehouse on Whittier Street there was a large painted skull, of all things.

And where there are skulls, there are cemeteries…

Cemetery Park

While it’s true that many cemeteries in NYC such as Green-Wood in Brooklyn and Woodlawn here in the Bronx were de facto urban parks after their construction in the mid-19th Century, Drake Park, at Hunts Point Avenue, East Bay Avenue, and Longfellow Avenue, is one of the few NYC parks that contains a cemetery*: the colonial-era burying ground of the Hunt and Leggett families.

*Prospect Park does — it incorporates an old Society of Friends cemetery.

There are several very ancient stones in the cemetery belonging to the Hunt family; some have been reinforced with concrete. I am unsure if the stone from 1749 (top right) was here originally — it could have been moved here from elsewhere. There are other stones as recent as the mid-19th Century. Drake Park was created in 1910.

The park’s namesake, Joseph Rodman Drake (1795-1820)was a poet whose work has been mostly forgotten by the 2000s but who had made quite a name for himself in his own era, the early 1800s, with his most famous poems “The Culprit Fay” and “The American Flag.” Drake was born in lower Manhattan, but discovered the then-bucolic fields of Hunts Point as a young man; in fact he would often brave the currents and rowboat here across the East River. While ill with tuberculosis at age 25, he requested to be buried in Hunt’s Point. One of his best friends was Fitz-Greene Halleck, who is likewise little-known today, but was read enough in the 1800s to have a statue in Central Park cast in his likeness.

East Bay Avenue

Hunts Point Avenue near Drake Park. I did mention this was the Bronx Iron Triangle.

New York Recycling Ventures, East Bay and Longfellow Avenues, which recycles between 60 and 80,000 tons a year. I missed the lengthy Longfellow Avenue mural, but the NY Daily News didn’t.

The city has been diligent in replacing Triborough Bridge signs to Robert F. Kennedy Bridge signs, even way out here in Hunt’s Point.

East Bay Avenue and Faile Street.

Death of a Diner

Apparently, the torch has been put to a pair of classic Hunt’s Point diners quite recently as of March 2009. Michael Engle and Mario Monti’s Diners of New York, published in 2008 by Stackpole Books, treats the East Bay at East Bay Avenue and Faile Street as if it were still open, giving out its phone number. Walking past, though, it looks as if it has been closed for more than a year. Some of its old trim remains. It was built by the Kullman diner manufacturer in 1955 (above left photo shows it as it was). We’ll see another deceased classic diner a little later on. The auto wrecker next door is still hanging in.

End of the Bronx

Approaching the East River, the streets become more and more barren, at least on the weekend. There is heavy industry, some manufacturing, and also toxic waste disposal and sewage treatment (seen below). This is the corner of Viele Avenue and Coster Street; Viele Avenue was named for General Egbert Lodovicus Viele (1825-1902), an Army engineer who produced the first draft of what would become Central Park. He was, of course, replaced on the project by Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.

Viele’s relevance here is that he also was among the first to conceive of Hunt’s point as a potential port and commercial center under the name East Bay Corporation, hence that street name. This, too, did not work out; but Viele’s map of Manhattan’s waterways and streams, produced in 1874, is still in use by engineers and builders today.

On the south side of Ryawa Avenue is the Hunts Point Sewage Treatment Plant, constructed in 1951. It is not quite as dramatic as Greenpoint’s Anareobic Digestion Boobs.

The Bronx is dotted with odd street names like Yznaga and Ryawa. It’s likely that “Ryawa” is simply an anagram for one of Viele’s projects, Railway and Water Association or perhaps, Railroad Yard and Warehouse Area.

Barretto Point Park

Barretto Point Park was constructed in 2007 on 5 acres of East River waterfront at Viele Avenue and Tiffany Street; its presence is heartening in that even in NYC’s most out-of-the-way, visitor-unfriendly areas, a brand-new park with views of the towering Manhattan skyscrapers is available. There is even a beach (“La Playita”), but in March, no Bronx bathing beauties were in evidence.

Hopefully this will be your webmaster’s only close approach to Riker’s Island.

Using the zoom lens, I photographed North Brother Island from the park. Look closely and you can just about make out the top of one of the abandoned hospital buildings on the island. In 1886, Riverside Hospital was built here that treated and quarantined people with contagious illnesses. Its mission expanded to include other diseases such as TB, typhus, typhoid fever, and polio. The most famous patient was “Typhoid Mary” Mallon (1869-1938), who was perfectly healthy herself but was a virulent carrier of typhoid fever. After infecting several people between 1900-1907 Mallon was quarantined on North Brother but released on the condition she not work with food. However, she inflicted typhoid fever on 25 others, and was returned to North Brother Island, this time for life. The ill-fated General Slocum tour boat grounded here after catching fire in the East River in June 1904, taking the lives of over 1000, most Lower East Side German immigrants on a church picnic.

South Brother Island was used by early 20th Century Yankee owner Colonel Jacob Ruppert for several years as a personal resort island. The immortal Babe Ruth was known to practice his swing, walloping baseballs into the East River. I’m not sure if anything from Ruppert’s era remains there. Both islands are now protected bird sanctuaries, but they do attract several intrepid urban explorers, such as ForgottenFans K. Jacob Ruppert (a descendant of the Colonel’s) and Marie Lorenz and Moses Gates.

Both Brothers can be seen from Barretto’s fishing pier, part of an old ferry dock.

The Midland Steel Warehouse Corporation operates out of several buildings in southwest Hunt’s Point, including this densely windowpaned building on Oak Point Avenue and Worthen Street.

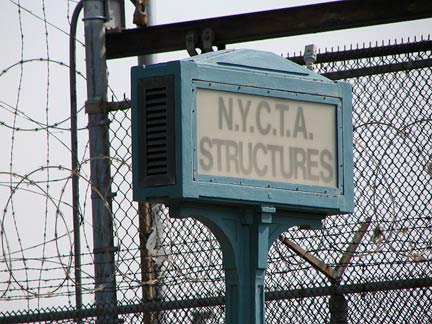

Imagine my surprise to find, across the street on Oak Point Avenue, a pair of Redbird subway cars, R-33 #8912 and 8913, on a short section of elevated rail! This is the NYCTA Tiffany Street Iron Shops, a training site for el structure maintainers. The el here is a replica complete with station platforms for training purposes. I was sure to photograph from the Oak Point Avenue median, to avoid any hassle from the security guard.

The Tiffany Yards are part of the Oak Point Yards, a repair facility — freight facility connected to the Fresh Pond Yards in Queens by the NY Connecting Railroad.

There was one more surprise to be seen here at the Tiffany Yards — an old station marker stanchion has been placed at the entrance. These used to be quite common in the five boroughs but only a couple of them are still in place…

At far left we see one, no longer standing, on Park Avenue at the Grand Central Terminal overpass, with the IRT blue indicator light. RIGHT, the West 190th Street station on Fort Washington Avenue near Fort Tryon Park.

Along Tiffany Street near Oak Point Avenue. This was the first restaurant I had seen on my trip, other than the burnt diners.

The winged wheel was often used to mark garage facilities in the early 20th Century.

Celeste Diner, Leggett Avenue and Barry Street. Again, the aforementioned diner book mentioned the Celeste as being open in 2008. It was a 1960 Kullman.

Bridge and Tunnel Club

The Curse Of Your Webmaster: Several establishments I have frequented over the years have recently met with gruesome consequences. The Tibbett Diner in Riverdale, The Waterfront Crabhouse in Hunter’s Point, and Totonno’s of Coney Island have all suffered severe fire damage in 2008-2009. Of course, Chumley’s, the Greenwich Village tavern where the ForgottenBook Party was held, suffered a wall collapse in 2007 and is slowly rebuilding.

The massive American Bank Note building can be glimpsed from Barry Street and Leggett Avenue. The street is named for Commodore John Barry, the “Founder of the American Navy.”

Hand painted sign, Barry and Leggett.

Jacob Froehlich Millworks, established 1865, Barry Street between Leggett and Oak Point Avenues. Their building doesn’t appear to have been built in 1865 (looks more 1900-1910-ish to me) but it’s a gem– a stolid brick factory with heavy window lintels in a region otherwise populated by low-rise garage facilities.

Preparing to leave Hunt’s Point for now, we cross over the Amtrak tracks on the second classic 1906 truss bridge seen today, this one supporting Leggett Avenue. Oddly I found no lamps of any kind on the bridge — it must be dark at night. When I passed under the bridge riding Amtrak, I had noticed that the masts once carried either crescent-moon or rad-wave incandescent luminaires, but these, too, have disappeared.

Southern Boulevard and Leggett Avenue. I have noticed on Bronx strolls, throughout the borough, that large apartment buildings located at busy intersections are often rounded, not angled as they are in other boroughs.

Anyone know how this came about? Are there bylaws for construction in the Bronx that necessitated this?

Former Ace Theatre, also known as the Congress, Southern Boulevard between East 149th and Avenue St. John. Surprisingly the commenters at Cinematreasures didn’t know much about its history; can any Bronxites fill me in?

Before boarding the train at East 149th, I noticed this object on the sidewalk. It might well have been one of the station marker stanchions I pointed out earlier.

Sources: History in Asphalt; McNamara’s Old Bronx, John McNamara; Landmarks of the Bronx, Gary Hermalyn and Robert Kornfeld, Bronx County Historical Society; The Bronx, It Was Only Yesterday, Lloyd Ultan and Gary Hermalyn, Bronx County Historical Society

photographed March 14, 2009; page completed March 15.

erpietri@earthlink.net

©2009

1 comment

[…] greening the borough. The Bronx is still home to some of the more industrial areas in the city. Hunt’s Point and Port Morris for example, can greatly benefit from more trees, community gardens and urban […]

Comments are closed.