I was lurching about Lower Manhattan on a May 2010 Saturday, completing my FNY self-imposed assignment — to locate every possible overlooked, forgotten-about and uncared-for detail in sight, photograph it, upload into my computer, prepare them for the internet (they’re always too large), research them, and assemble a page about them, which is viewed by approximately 2300 people a day.

Lower Manhattan, which I consider everything below Fulton Street, is literally where the City of New York began in the mid-1620s, when the Dutch made a permanent settlement after the Italians, the Spanish, et al. had given it the once-over and decided to pass. The British, though, correctly deduced this was a prime spot especially as a port, and forced out the Nethermen as a ruling body in 1664. Dutch families left some strange place names, and a winding street layout conceived well before the gridiron system imposed in the 1800s.

Wall Street, as seen from Broad; right, vice versa. Since 9/11/2001 Wall Street and part of Broad have been closed to traffic, but only lately have the DOT/NYPD found ever more ingenious ways to pen in the tourists and assert control over the space, which is the real object.

GOOGLE MAP: FNY LOWER MANHATTAN

I wandered all around the Financial District, somewhat aimlessly, without a real objective — when I spied something Forgottenworthy, I grabbed it. This took up the greater portion of about 4 hours. The FD, while it will always be home to NYC’s financial industry (some say the greedheads) — finance, along with tourism, is the chief driver of NYC’s profit these days. NYC’s role as a port, as well as a manufacturing center, has faded dramatically the past three decades, and I’d imagine the majority of New Yorkers work white collar now. The city seems determined to drive out the remaining industry it has and convert it to residential and entertainment: witness the evisceration of the Meatpacking District and the city’s unending efforts to drive out the metal and scrap workers of the Iron Triangle, Queens, mobbed up or not. (I call it the Eloization of New York, after the H.G. Wells Time Machine characters of the future who mostly lazed about eating fruit, only to provide meat for the Morlocks.)

Since I sense a rant coming on, I’ll get back to the photos.

18 Beaver Street (at New Street) caught my eye not only for the old school Yip’s Restaurant sign but what I found on the pediment at the top. It was likely before this particular 3-story building was constructed, but 18 Beaver was once the home of Thomas Williams, scion of the family of “the oldest and largest firm in the world dealing in mahogany and other imported cabinet woods.”

The girl on the pediment is likely Hebe. I am not trying to be insulting — Hebe (pronounced AY-bay) was the ‘cupbearer of the gods’ in classic myth. One of the little details that Beaux Arts architects, who no doubt studied the classic myths in school, provided on buildings to make them beautiful. A trifle, lost from the practices of today.

The building next door, 20 Beaver, is over a century old and has a varied history, according to The Masterpiece Next Door:

20 Beaver Street looks like a Federal-style (right? Federal?) warehouse. Some net-sleuthing connects the site (and probably the building itself) to the Holmes & Haines cabinetmaking company starting at some indeterminate point early in the 1800s. By 1901, it is home to George A. Kessler & Co.; Kessler was a wine merchant written about in numerous New York Times articles, including this one about his escape from the Lusitania disaster and another on a mad expensive $300-a-plate “polar party.” Later it became home to Samuel Lakow‘s custom office furniture business.

While the Lakow office furniture wall-dog ad has been expunged from North Moore and Hudson Streets, Mr. Lakow will apparently have a presence at 20 Beaver for as long as it stands.

26 Beaver Street used to be the headquarters of Norton Lilly International, a major shipping concern that is still in business, though apparently without an office in NYC. Downtown used to be a center for shipping snd steamship company offices; the Cunard Building is nearby on 25 Broadway. Here’s a brief history of Norton Lilly.

Right in front is a now-rare Type 1 BC Bishop Crook. There are only about 3 or 4 of these remaining — I profiled the one on Centre and Grand Streets in May 2010. They first appeared in NYC streets in the Nineteen Oh’s.

I’m a big fan of the “ladder rest” crossbar on older Bishop Crook species; later models did away with this hommage to gaslights. This one has been outfitted with a 1980s-era Mission Bell lume, which looks too big for it.

Before my mother worked in Manufacturers Hanover HQ (now JP Morgan Chase) at 4 New York Plaza in the early 1970s (JPMC just sold the building, actually) I seem to remember her working at 75 Broad Street, the International Telephone Building.

It was built in 1929 at South William Street as the headquarters for ITT Corporation, once an international telephone and telegraph giant. During World War II the building was a hub for communications with American submarines operating in the Atlantic Ocean. But ITT moved out long ago, and over the years 75 Broad became a multitenant office building. The building was taken over in default in the late 1980’s, when the future of office properties in the downtown area seemed bleak. NY Times

There are very few buildings in lower Manhattan that were built before 1835. In December of that year a tremendous fire tore through the area, devastating everything, including many structures going back to the Dutch days of the early to mid-1600s. There was a cold wave on at the time, and long before electric power created a ‘heat barrier’ around the NYC area, the air temperature approached twenty below. Fire crews couldn’t get water on the fire before it froze.

However, a walk on South William Street, a short, curving path from Broad Street to where William meets Beaver will reveal a series of buildings that appear to have been built during the Dutch era, with stepped Flemish-style gables. 13 and 15 South William are the most notable, constructed by the very busy C.P.H. Gilbert. However the date of construction, 1903, is conveniently displayed below the roofline.

The two ends of Mill Lane, a short path between Stone and South William, honoring a long-vanished mill, is one of the shortest streets in Manhattan (Edgar, between Trinity Place and Greenwich Street just north of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel exit, takes the title according to the people who measure these things). We’ll see some of these oddments on this page. Mill Lane is much narrower and less trafficked than Edgar, though, and may well be the least-noticed of any street in Manhattan.

I profiled Stone Street in FNY several years ago. I was fooled by its redressing for a movie set, and I thought they had gone whole hog with the throwback treatment. The interesting thing is that Stone Street, except for a chunk removed to build 85 Broad Street in 1983, pretty much looks the way it did in the 1920s, with one obvious exception.

Long before Department of Transportation commissioner [in 2010] Janette Sadik-Khan began closing streets all over town to create pedestrian plazas and bike paths, Stone Street was closed to car traffic to create an outdoor food court and downtown Restaurant Row. Even on the weekends, there is table service right in the middle of the street.

The street can also boast some interesting wrought-iron work, including an elaborate fire escape. A mast that once held both a pendant streetlamp and an orange fire alarm light is still in place.

The new 47-story gray luxury living tower with gold trim at 15 William Street is called the William Beaver House, named for the two streets that intersect here. A piece of the old Delmonico Restaurant can be seen at the left side. (This is a Five Points still in place, as three streets meeting produce five corners). It was designed by Andre Balazs, who also built the Standard Hotel straddling the High Line in the Meatpacking.

I’m sure condo owners will be repairing to the Killarney Rose on nearby Beaver, with its neon sign in Peignot type proclaiming its 1968 lineage.

82 Beaver Street was once the Munson Line headquarters, another steamship line:

The Munson Steamship Line, frequently shortened to the Munson Line, was an American steamship company that operated in the Atlantic Ocean primarily between U.S. ports and ports in the Caribbean and South America. The line was founded in 1899 as a freight line, added passenger service in 1919, and went out of business in 1937. wikipedia

Terrific stanchion lamp, entrance, 87 Beaver/67 Wall.

Somewhat resembling the Fuller, or Flatiron, Building, and dating to the same era, is the Beaver Building at the northeast end of Beaver Street where it meets Wall and Pearl Streets. I hadn’t noticed the brightly colored terra cotta at the top of the building, but The Masterpiece Next Door didn’t. It was once the tallest builing in the immediate area, but it’s dwarfed today. The NY Cocoa Exchange was founded in 1925 and has merged a couple of times since, and is now a part of the Coffee, Sugar and Cocoa Exchange, a subsidiary of the New York Board of Trade.

I have always been fascinated by the ashlar stone basreliefs surrounding the arched entrance to the former Seaman’s Bank for Savings HQ at 74 Wall Street (built 1926), just west of Pearl. It must have been something, though, before the boring metal front and glass doors were installed. The bank published this extraordinary subway map in 1939.

The unheralded 70 Pine Street, the American International Building, AIG (formerly Cities Service Building — Citgo), is among NYC’s tallest at over 950 feet, boasting 66 floors. It was completed in 1932 by architect Henry Dougherty, making it a contemporary of the Empire State Building. It was the first skyscraper featuring double-deck elevators (that have since been altered). At the Pine Street and the Cedar Street entrance around the block, you will find stone miniatures, since the building can’t really be appreciated from down the street –it’s surrounded by so many other tall towers.

In contrast to the Deco AIG Building, the rest of the north side of Pine street between Pearl and William is lined with darkly brownstoned Romanesque Revival buildings, most notable #60and #56.

#60 is the landmarked Down Town Association Building, built in 1886-1887 by architect Charles C. Haight for a private gentlemen’s club. The building has a 2-bay extension on its east side, finished in 1911. The LPC provides a complete description.

#56 Pine, originally the Wallace Building, was completed in 1894 by Swiss architect Oswald Wirz. It was renovated for luxury living in 2005. This too has been given landmark designation:

In choosing the Romanesque Revival style for his building, Wirz used forms suggesting strength and durability, and gave the whole composition a highly individualistic interpretation. At 56-58 Pine Street, the broad, round arches of the first story openings are characteristic features of the Romanesque Revival style. They are linked by groups of truncated colonnettes in polished granite. The deeply set windows, the rough-cut stone found at several locations on the facade, the variety of materials, and the Byzantine-style ornament further distinguish this building as being in the Romanesque Revival style. To all this Wirz added stylized faces and grotesque heads which give this building an unusual decorative character. Set amid the swirling spandrel designs or placed high up on the facade, the faces are not immediately evident, but some study reveals the unique and highly evocative nature of this building. LPC

I continued west along Pine Street, noticing the names above the doors: investment bank A. G. Becker & Co. (based mainly in Chicago)…

and the Caledonian Insurance Company, founded in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1805. The building is part of lower Manhattan’s Insurance District, centered between Pine Street, John Street, Broadway and William Street. Caledonian bought the plot in 1899 and constructed the HQ at 50-52 Pine shortly thereafter. The building is now residential.

Our Lady Of Victory Roman Catholic Church, serving the many Catholic office workers in the area and an increasing number of downtown residents, is a relatively new addition to the north side of Pine at William Street, having been completed in 1946. It was founded by Francis Cardinal Spellman in 1944 and is also known as the War Memorial Church.

William and Cedar Streets, Mutual Life Insurance Company of New York Building, completed 1897. The company later moved uptown and inspired the title of Tommy James’ 1968 classic “Mony Mony“: the story goes that James saw the flashing MONY sign from his hotel room.

True story: I had the track done before I had a title. I wanted something catchy like “Sloopy” or “Bony Maroney,” but everything sounded so stupid. So Ritchie Cordell and I were writing it in New York City, and we were about to throw in the towel when I went out onto the terrace, looked up and saw the Mutual of New York building (which has its initials illuminated in red at its top). I said, “That’s gotta be it! Ritchie, come here, you’ve gotta see this!” It’s almost as if God Himself had said, “Here’s the title.” wikipedia

Detail, Cedar between William and Pearl. The south side of Cedar is actually the backs of the former insurance companies that line the north side of Pine.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 33 Liberty between William and Nassau, literally has more gold bars (belonging to many countries) than Fort Knox stored in five sub-basement levels, and with gold over $1200 per ounce in May 2010, that’s not a bad haul, worth almost $100B. York & Sawyer constructed the fortress in 1935. It is the largest of 12 regional Federal Reserve Banks.

The street closing is due to a March 2010 crane crash at 80 Maiden Lane, home of the NYC Department of Investigation.

Louise Nevelson Plaza, triangle formed by Maiden Lane and Liberty and William Streets. With due respect to sculptor Nevelson (1899-1988), the 1978 installation, Shadows and Flags, has always looked like twisted scrap metal to me. Of course, I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like.

Curving Maiden Lane at Nassau Street. The street follows the course of a now-underground stream; the story goes that young Dutch women used to do the family wash in the stream, hence the name. Note the buildings gently curve along with the street.

GOOGLE MAP: FNY LOWER MANHATTAN

We’re a little south of the Soho Castiron Building area but 63 Nassau, just north of Maiden Lane, built in the 1840s, is among the first examples of the genre; some experts believe castiron pioneer James Bogardus was the man who installed the castiron front in 1860. It was built for ironmonger Augustus Thomas. There are two bas-reliefs of Ben Franklin, and the two depicting George Washington were mysteriously removed.

[2012: Daytonian in Manhattan has an interesting piece on this buildings, with a wealth of details.]

Liberty Place, originally Little Green Street (in the early 1800s) is another of lower Manhattan’s mysterious one-block streets, running between Liberty and Maiden Lane west of Nassau. There are residences and businesses even on Manhattan’s tiniest routes. Most of the street is shrouded by a construction canopy (most of Lo-Man’s short streets are subject to this fate). 21-23 Maiden Lane can be seen at the north end of this perpetually shady street. London’s Little Green Street is a masterpiece of 18th Century preservation.

The Downtown Alliance black and white downtown signs have been in place for about 10 years, and the design, encompassing a photo of a local landmark (Federal Hall at Nassau and Wall Streets in this case) and house numbers, should be adopted all over town.

Classic yellow and black liquor store sign, Maiden Lane east of Broadway.

I had not noticed that #1 Maiden Lane is named for the now-over 125 year old Bathman’s Jewelers.

On the corner of Broadway and Maiden Lane is NYC’s only working clock embedded in the sidewalk, first placed there in 1899. It has been attacked by vandals and been trodden on for years but it keeps on ticking (with the help of an electric motor.) William Barthman first set up shop in the financial district in 1884. In 1946, the NYPD estimated that fully 51,000 people stepped on the clock daily between 11AM and 2PM.

An organization known as the Maiden Lane Historical Society set up a plaque in 1928 at Barthman’s depicting what Broadway and Maiden Lane looked like that year.

Barthman’s Jewelers no longer is located in the corner store, at the clock. It moved a few doors down to 176 Broadway some years ago.

…[T]he 119-year-old jewelry store sits at what was once the heart of a bustling gem and gold-filled bazaar. In fact, the jewelry trade in New York City dates back hundreds of years, to a time when small workshops and foundries began popping up along Maiden Lane between Broadway and Nassau Street. By 1795, the street had become a jewelers’ hub.

Sales of necklaces, brooches, watches, and chains continued at a steady clip along the narrow cobblestone street well into the next century, experiencing an even greater surge in the late 1800s and early 1900s as a then new diamond trade brought waves of settlers to the city. These jewelers, mostly European Jews, quickly opened their own businesses downtown. Soon Maiden Lane’s narrow sidewalks were overrun, and the buzzing jewelry district swelled to nearby Nassau and Fulton Streets and then inched still farther north to the Bowery and Canal Street.

At the northwest corner of the Bowery and Canal, Manhattan’s jewelry sector continued to flourish, eventually displacing the original Maiden Lane hub. But just as the success of the diamond business grew over time, so too did the city itself. Gradually, more affluent merchants relocated even farther north. After World War II, today’s midtown jewelry hotspot, located on West 47th between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, had been firmly established, having outpaced the downtown concentration of stores. Lower Manhattan Info

One World Trade Center (the Freedom Tower), expected to be completed in 2013, rises at the west end of Cortlandt Street. There are two subway stops on Cortlandt, which is tied with Bowling Green and High Street in Brooklyn as the shortest streets (one block) with subway stops named for them. Both Cortlandt and High streets used to be much longer, but construction ate away at them.

Broadway and John Street, Corbin Building, designed in 1889 by Francis Kimball. Renowned for his decorative use of terra cotta, the Renaissance Revival building is chock full of detail and carved brownstone. It is named for railroading magnate Austin Corbin:

Austin Corbin was a successful businessman who did extremely well on Wall Street. In 1873, Corbin and his family moved to Coney Island on the advice of his son’s doctor, for his son was gravely ill and the doctor recommended the sea and salt air for comfort. After the move, Corbin, then president of the Long Island Railroad, saw potential profits in the development of a seaside resort. He then bought 500 acres and started the Manhattan Beach Improvement Company. In 1877, this company built the Manhattan Beach Hotel, followed in 1880 by the Oriental Hotel. The Manhattan Beach Hotel was located on the far eastern portion of Coney Island (today’s Manhattan Beach). His New York and Manhattan Beach Railroad would eventually serve his hotel. NYCSubway.org

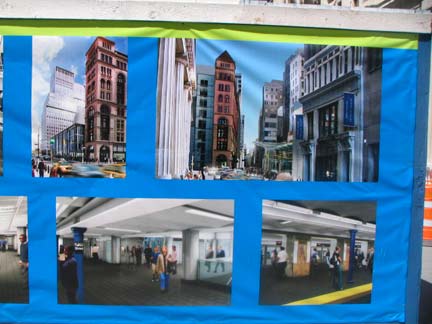

The Fulton Street Transit Center is an ongoing project that will provide easier connections to the many subway lines in lower Manhattan, providing connections between the IND 8th Avenue Line, the BMT Broadway Line, the IRT Lexington Avenue Line and the BMT Nassau Street Line. There will eventually be a glass-walled entrance building with an egg-shaped roof ornament at Fulton Street and Broadway. The Corbin Building was going to be torn down to make way for the project, but preservationists prevailed on the city to save the building. The 19th Century and 21st Century buildings will abut each other and make an odd coupling.

John Street United Methodist Church, the third iteration of a church began by Irish Wesleyan Methodists and first constructed in this site in 1768. This church building (1841) is older than the present Trinity Church building at Wall Street and Broadway, but not as old as St. Paul’s Chapelon Broadway and Fulton Streets (1766). Philip Embury was the founder of the first Methodist society in North America.

A slave named Peter Williams was one of many African American members of Philip Embury’s society. He became sexton of Wesley Chapel and, with James Varick and others, formed what later became the Methodist Episcopal Zion Church.

In 1817 the chapel was torn down to make way for a larger structure, dedicated in 1818. A third (and smaller) edifice was erected in 1841 and is still in use today. United Methodist Church

Dutch Street, a short passage between John and Fulton east of Nassau, turns up on maps as early as 1776 and was first named around 1789. The Old Dutch Church stood nearby on William between Ann and Fulton from 1769-1875 and the street’s name may derive from it, according to Sanna Feirstein’s Naming New York. Since Dutch Street is perpetually shrouded with scaffolding, I’ll show you the street sign, which shows the sailing ships moored at nearby South Street Seaport.

Twisting Gold Street’s oldest section from Maiden Lane north to John Street has been called Rutgers Hill and Golden Hill early in the 19th Century; an important Revolutionary War battle took place there, as well as a long-vanished gold exchange. I have the whole story on this FNY page.

Keuffel and Esser products were staples in the pre-calculator era,since the firm produced slide rules, compasses, telescopes, imported planimeters and other optical instruments for over 100 years. The company was founded in 1867 by immigrants from Germany, William Keuffel and Herman Esser. Though K&E built a large factory building in Hoboken, NJ that was owned by K&E until 1968 their 127 Fulton Street building, constructed in 1878 and topped out at 8 stories in 1892, still proudly bears the name, with the front stylized with a measuring tool motif.

One of the more interesting aspects of K&E was their use of spiders, whose webs privided filaments used in crosshairs of their range finders, as did other firms.

Unusual choice for a corner light post at Fulton and Nassau Streets, as this type is usually found in city parks and it’s unusual to see them festooned with street and one-way signs.

James Gordon Bennett Building, NW corner Fulton and Nassau, another designated landmark:

The Bennett Building, constructed in 1872-73 and enlarged in 1890-92 and 1894, is a major monument to the art of cast-iron architecture. Ten stories high with three fully designed facades fronting Fulton, Nassau, and Ann Streets, it has been described as the tallest habitable building with cast-iron facades ever built. Commissioned as a real estate investment by James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the publish of the New York Herald newspaper, the Bennett Building was originally a six-story French Second Empire structure. Designed by the prominent architect Arthur D. Gilman, whose Boston City Hall was instrumental in popularizing the Second Empire style in America, the Bennett Building appears to be the architect’s only extant work in the style in New York. Gilman was also an important pioneer in the development of the office building, and the Bennett Building is the sole survivor among the major office buildings he designed. Second Empire office buildings flourished in Lower Manhattan after the Civil War; this is one of two such buildings with cast-iron fronts still standing south of Canal Street. In 1889, the Bennett building was acquired by John Pettit, a leading real estate investor who commissioned architect James M Farnsworth to enlarge the building to its present size. LPC report

145 Fulton, between Broadway and Nassau, is a rare peak-roofed building in lower Manhattan. In a former life, it was Whyte’s Restaurant:

In 1904, Edward E. White moved his family from St. Louis to New York City. In 1908, Edward established Whyte’s Restaurant at 145 Fulton Street. He spelled the name with a “y” as a mark of distinction.

“Built in a kind of Alpine chalet style, Whyte’s strove to retain an Old-World aura, with its dark paneling, gilt-framed portraits, and long oak bar with well-shined brass spittoons. The Bar was a famous watering spot for downtown executives, with groups of insurance men, stockbrokers and politicians taking what seemed to be assigned places at the rail.” With his four sons — Neil, Edward H., Joseph and Frank — Mr. White made the establishment exceedingly popular. Unfortunately, Edward did not live to enjoy the fruits of his labor; he died September 14, 1918. His wife Mary took over as president of the Corporation.

The family sold the Fulton Street Restaurant early in 1929 to a group employed by the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, which they renamed Willard’s. On March 10, 1929, Whyte’s moved to the Lefcourt National Building at 521 Fifth Avenue. Because of the Depression and an annual rent at 521 Fifth of over $100,000/year, the Whyte establishment declared bankruptcy on February 5, 1932. Shortly after, the group that operated the old Fulton Street address (then known as Willard’s) had to close their doors, and the Whyte family returned to 145 Fulton Street and reopened in June of 1932.

After the death of the last son, Frank, December 25, 1943, the restaurant was operated by long-time manager, Raymond Francis Hopper, who became the subsequent owner.

A second Whyte’s was opened circa 1954-55 at 344 West 57th Street. On April 20, 1971, Whyte’s on Fulton Street was forced out because it was unable to renew its lease. At that time, owner Raymond Hopper stated: “Whyte’s uptown restaurant at 344 West 57th Street will continue in operation.” Unfortunately, Mr. Hopper died April 28, 1971. Restaurantware Collectors

Another survivor at Pearl and Fletcher Streets, the Pearl Street Diner, is a Kullman Diner constructed in the 1950s, with possibly its original neon sign.

Only the facade of 211 Pearl, an 1837 townhouse, has been retained to front high-rise luxury living and a parking garage.

Where brick meets brick: Belgian block paving on both Fletcher and Front Streets.

160 Front is emblazoned “New Jersey Zinc” on the decorative metalwork above the front entrance. I thought I’d have a hard time finding any information about this, but Starts and Fits has the lowdown…

The building was designed for the NJ Zinc Company by architect Henry Hardenburgh, constructed in 1918, and was his final project. The metal used on the ornamentation is zinc, as you might expect. NJ Zinc was purchased several years ago by the Horsehead Corporation. Note the horse’s head on the entablature; it predated the purchase.

Concluding this particular swing of lower Manhattan at the east end of John Street, facing the back end ofSchermerhorn Row at South Street Seaport. At one time there was a short inlet here where boats docked, Burling Slip. The city is builing a play area calledImagination Playground here.

Above right: the retro-gaslights (powered by electricity) in the mid-1980s at South Street Seaport are now almost 3 decades old and are getting kind of elderly themselves.

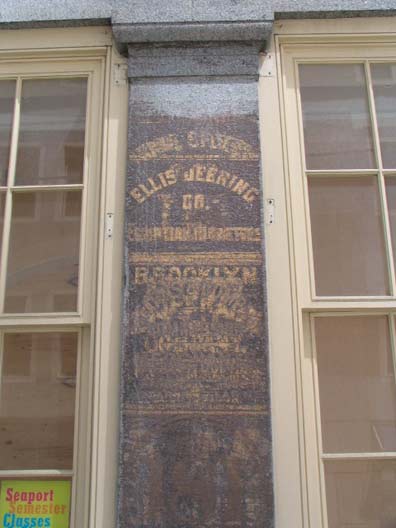

Palimpsest of ancient billboards on Front north of John.

page completed May 20, 2010

©2010 FNY