In May 2016 I decided to walk up Pearl Street’s entire length from Battery Park to Tribeca. It’s an oddly positioned street, as far as downtown goes, first running northeast, then gradually turning northerly and even westerly. Its entire length once ran to Broadway and Thomas Street, though it has been trimmed back from that due to mid-20th Century constructions. Because of the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s two separate landmarked districts, Pearl Street, unlike most downtown Financial Street ways, looks much as it did in the 19th Century along some stretches; other streets downtown run through concrete, masonry or glass canyons.

“Pearl” is the street’s original name. It is on the southeast section of the original Dutch street plan of Manhattan laid out in the early to mid 1600s and in those days was called Parelstraat or Parelstraet, “pearl” found by the massive oyster beds found in New York Harbor, which produced jewelry as well as sustenance to the area economy into the 20th Century before the waters became polluted and the oyster beds dried out.

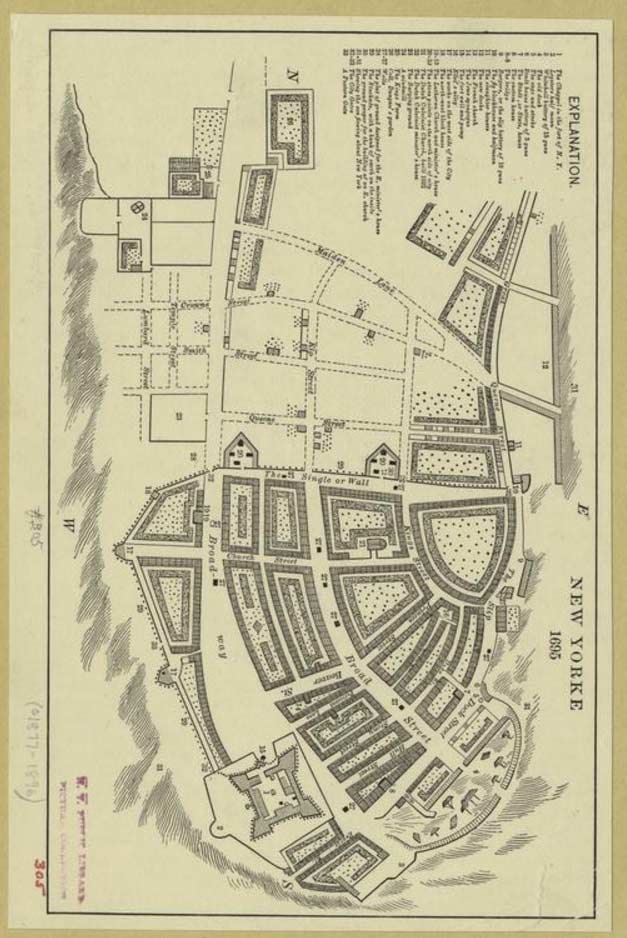

This map was produced in 1695, about 30 years after the British sailed in with a massive fleet and conquered Manhattan Island without a shot fired. Soon after that the Dutch streets were given British names. On this map some of the street names used today had already been assumed such as Broadway, Broad Street, and Beaver Street.

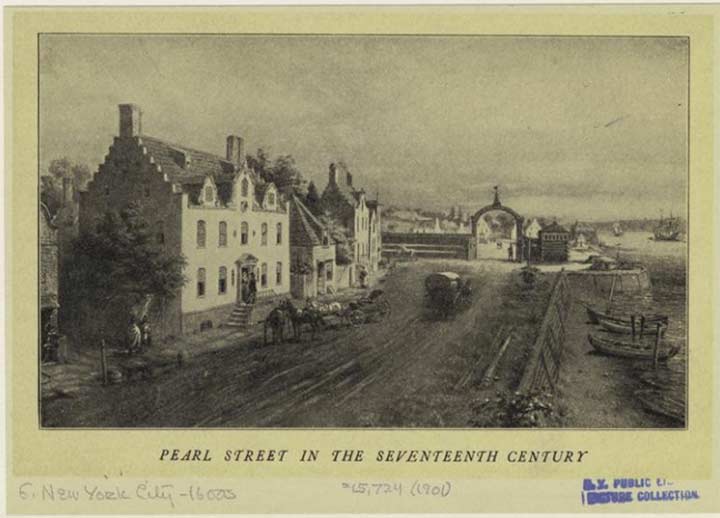

Pearl Street marked the eastern shoreline of Manhattan and so, the British named it Dock Street from the Battery as far as Hanover Square and north of that, Queen Street. After the Revolutionary War the British evacuated Manhattan in 1783 and streets were again renamed to eliminate references to the Crown and so, Queen Street reverted to Pearl. In this engraving the East River is seen at right with the stepped Flemish-style buildings then in vogue lining the street on the left.

In this street plan of 1729, not all the streets yet existed at least along the northern edge. Queen Street runs along the East River and makes the same bends and curves that Pearl Street does even today, even though there is no longer a shoreline to conform to.

Notice the fork in the route near the top. At this point Queen street diverged into Cherry, which ran northeast into what is now the Lower East Side, while the beginnings of a curve to the northwest and west can be seen. Pearl Street continues to follow this path today.

This 1797 map depicts the north end of Pearl Street. It is one of the main streets in an odd area today where the street plans of Downtown and the Lower East Side came together in a confusing pattern. Today most of these streets have been wiped off the map –it happened gradually over decades. The Brooklyn Bridge claimed some, the Southbridge Towers housing project claimed others and the NYPD Headquarters built in the 1970s claimed still more. Today Pearl Street turns west and by about 1812 had assumed the path of Magazine Street, which had been laid out in the late 1700s and named for gunpowder magazines, buildings designed to store the explosive materials used in weapons production.

Note “The Hospital” depicted at Broadway and Pearl. This map was made during the early years of New York Hospital, founded in 1771 and moved uptown in the 1870s; after several mergers it’s now New York-Presbyterian Hospital. The Fresh Water Pond shown is Collect Pond, which wasn’t so fresh by 1797. Eventually it was drained into the Hudson by a canal that is marked by today’s Canal Street. The area surrounding Cross, Orange and Magazine Streets was Five Points, one of Manhattan’s worst slums for much of the 19th Century.

This 1850 map shows the north end of Pearl Street at its longest. Until the mid-20th Century it served as the dividing line bwteeen the small streets scattered around east of City Hall, most of which have now vanished, and the more rigid grid of the Lower East Side.

Pearl Street begins at 17 State Street, the distinctive curved facade seen from the Staten Island Ferry as it approaches Manhattan. It was designed by the Emery Roth architectural firm and opened in 1989. It stands on the site of what was the Seaman’s Church Institute hostel for mariners, which subsequently moved out of its 1991 HQ on Water Street in 2010 in favor of Newark, NJ. Keith Haring’s “Two Dancing Figures” has been accompanying the curved tower since its opening.

Between State and Whitehall, Pearl Street looks nothing like when our next guest was born here…

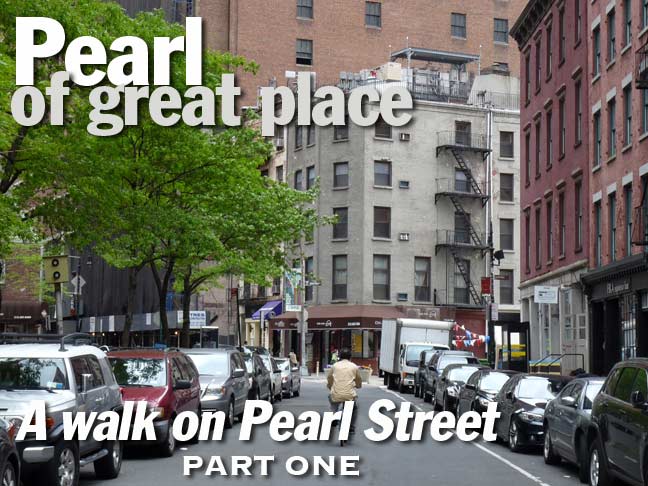

It’s a small, pigeon-splattered plaza in back of #17 State in which, on the aluminum wall behind a glass partition, you’ll find a bust of Herman Melville. It’s fitting that the Seaman’s Institute was here for years, since Melville, who wrote extensively about the sea, was born in a house at #6 Pearl Street in 1819. As a young man, Melville sailed extensively, encountering pirates and cannibals and participating in a mutiny, all of which flavored his writing career upon returning to the States.

From Moby-Dick (1851):

Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. Go from Corlears Hook to Coenties Slip, and from thence, by Whitehall northward. What do you see? – Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries. Some leaning against the spiles; some seated upon the pier-heads; some looking over the bulwarks of ships from China; some high aloft in the rigging, as if striving to get a still better seaward peep. But these are all landsmen; of week days pent up in lath and plaster – tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched to desks. How then is this? Are the green fields gone? What do they here?…

Melville’s most popular work set in NYC was “Bartleby the Scrivener,” set in one of the downtown counting-houses in today’s Financial District, about an enigmatic copier (scrivener) who would “prefer not to” do any of his assigned tasks.

The plaza was also home to New York Unearthed, a quirky museum that consisted of objects dug up during building construction.

Of the 2 million objects that comprised the largest trove of archeological objects from New York City’s past, there was a handful of coffee beans from an 1835 fire, ancient oyster shells, Delftware china brought here by the Dutch, some of it from China; porcelain marbles from the bygone Greenwich Village of Henry James; a coin from 1590 that is believed to be the oldest European object found within the five boroughs; and much, much more. The two-story space was designed by the studio of Milton Glaser, famous for his “I Heart NY” logo. After the museum closed in 2005 because its patron, the South Street Seaport, ended funding, most of the contents were moved to an Albany museum.

Whitehall Street looking north from Pearl Street. The massive Customs House building (officially named for first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, who is buried in nearby Trinity Cemetery), now the George Gustav Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian Smithsonian Institution, looms up ahead. One of the foremost examples of the Beaux Arts style, the Customs House was designed by Cass Gilbert and built in 1907. Before income tax was instituted in 1916, customs, or tax on the importation of goods, provided the bulk of the income for the federal government, and NYC was the nation’s biggest port.

One of the shortest streets in a part of town that has a number of them, Moore Street runs for one block between Water and Pearl north of Whitehall. There was no obvious “Moore” in the area in area records in the colonial era it could have been named for, so tradition holds that it was named for the many ship moorings along Queen Street. All Manhattan territory east of Pearl Street is built on landfill. An extra block of Moore Street east to South Street was wiped out by the New York Plaza complex in the early 1970s.

At left, and seen in photos above, a reverse L-shaped lamppost installed by the Downtown Alliance. The posts appear frequently in southern Manhattan and a group have also found their way to Jackson Avenue in Long Island City.

Fraunces Tavern, at Pearl and Broad streets, is one of Downtown’s most popular tourist attractions and so it’s hardly “forgotten.” It’s a museum and somewhat pricey restaurant combined into one. However, a lot of people who visit NYC, and probably most of the people who work Downtown and pass it every day believe they are walking by the very same Fraunces Tavern where George Washington bade farewell to his charges at the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783. The truth is rather cloudier.

Samuel Fraunces, a West Indian by birth, was famed for his cooking and operated the Queen’s Head Tavern for several decades in the 18th Century, hosting meetings of the Sons of Liberty and later the New York Provincial Congress, but the British occupancy of New York ruined him financially. He was employed by Washington as a steward and chef, and his tavern became a meeting place for the nascent Departments of Treasury, Foreign Affairs and War.

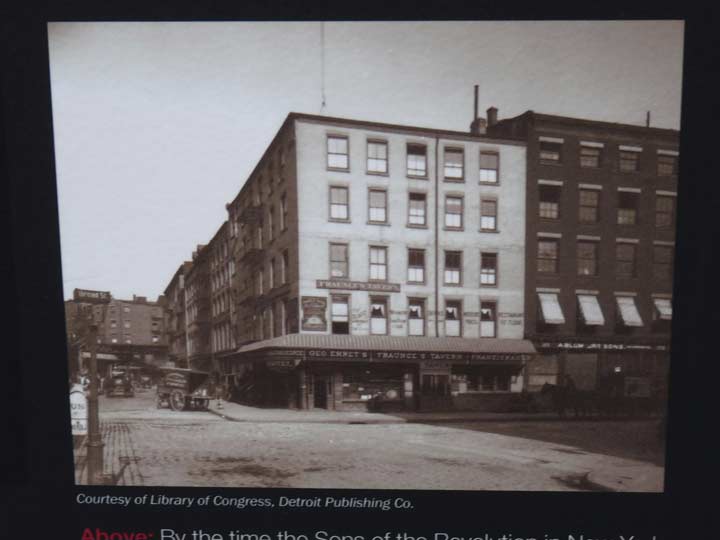

This is a photo of the Fraunces Tavern building shortly before it was slated for demolition in 1902. It was, however, saved and “reimagined” as a Colonial Revival building under architect William Mersereau. The Long Room, in which Washington made his speech, presents a typical 18th Century tavern room. Many tour guides show it as the “Real McCoy” but since of course no photos exist of the tavern as it was in 1783, the restoration was highly conjectural.

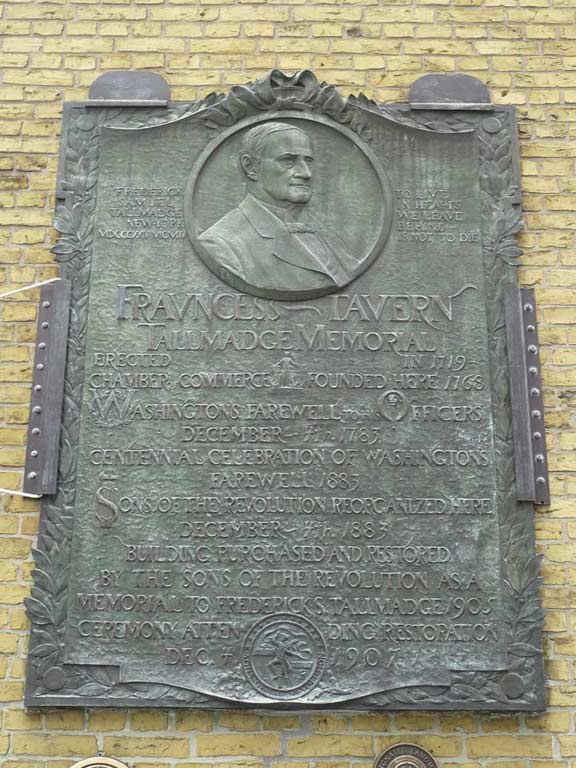

On the exterior of Fraunces Tavern are placed a number of plaques and memorials, some quite intricately made such as this one placed in 1883 to celebrate the centennial of Washington’s speech and the organization of the Sons of the Revolution the same year. The plaque was placed in 1907 after the “reimagining” of the tavern had been completed. The plaque also memorializes Frederick Samuel Tallmadge, Frederick Samuel Tallmadge (c.1823–1904), president of the New York Society of the Sons of the Revolution from 1884 until his death in 1904.

Two plaques recognizing the tavern’s place in history.

Sons of the Revolution is a hereditary fraternal organization which was founded in 1876 and educates the public about the American Revolution. The General Society Sons of the Revolution is the SR’s national organization and is a Pennsylvania non-profit corporation. Located at Williamsburg, Virginia, it is governed by a board of managers, an executive committee, officers, standing committees and their members, and staff. The general society includes 28 state societies and 14 chapters in the United States, as well as societies in France and Mexico. [wikipedia]

The New York branch holds an annual walk in downtown Manhattan early in the morning of July 4th at sunrise that annually sells out.

The Bishop Crook lamp on the corner of Pearl and Broad is one of a few remaining downtown “Crooks” from the early 20th Century; at this point, it’s hard to tell them apart from the “retro-Crooks” that started appearing in the 1980s. This one still has a space where the fire alarm lamp bracket had been installed; it was removed a few years ago.

The buildings on the south side of Pearl, along with the north side of Water, the south side of Coenties Slip and the east side of Broad, comprise the Fraunces Tavern Block Historic District. #58-66 Pearl were all built in the mid to late 1820s with the exception of #64 which dates to 1858.

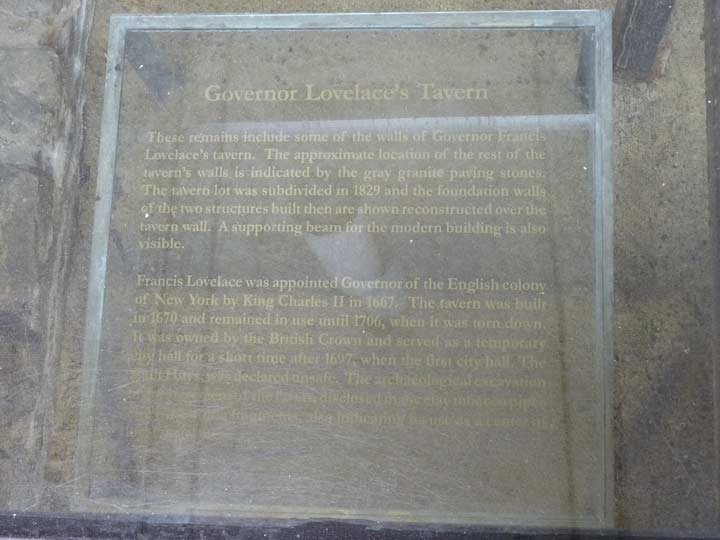

#66 Pearl, at the corner of Coenties Slip. The site is historically and archeologically significant. From the LPC Designation report:

Philipse owned a vast amount of land in Westchester County; his manor in Yonkers still stands. He built the first bridge over Spuyten Duyvil Creek, named Kingsbridge– the inspiration for over a dozen Bronx place names.

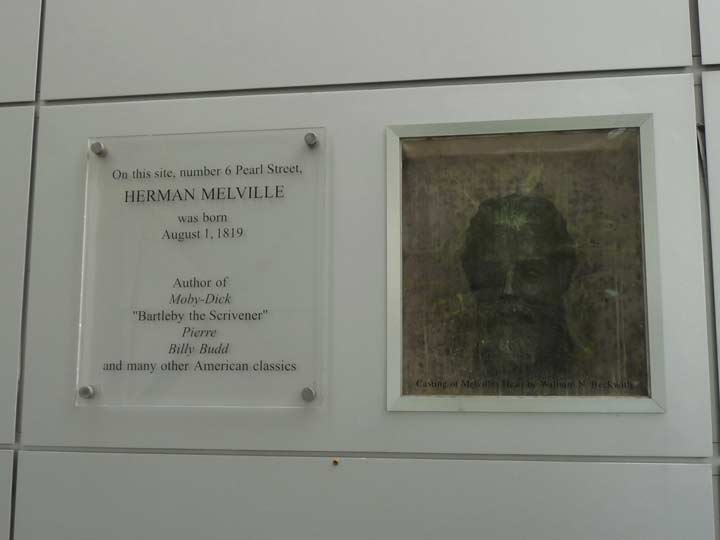

Meanwhile on the west side of Pearl at Coenties Slip, at the 85 Broad Street skyscraper, you can find displayed beneath the sidewalk remnants such as a tavern belonging to Francis Lovelace, New York’s second British governor. The tavern was discovered in 1980 during excavations for 85 Broad; archeologists had been hoping to find remains of the Staat Huys (State House), the old Dutch city hall, but this was the next best thing.

According to legend Coenties Slip takes its name from Conraet Ten Eyck and his wife Antje, who owned the property where the alley stands now in the 1600s. In English, their names would be Conrad and Ann Of The Oaks.

Colonial governor William Kieft built the Stadt Huys, or City Hall, in 1641 because he was tired of entertaining visitors at his home and wanted an inn to send them to. Twelve years later, it became the first city hall of New York. Unfortunately, it is believed that later construction in the area destroyed the building’s foundations. The excavators did not actually find any remains from the Stadt Huys, but they did recover evidence of a building that once stood next to it, the Lovelace Tavern. This tavern served as New York’s second city hall, from 1670 to 1706, when in burned down. Inside the preserved foundation walls, excavators found thousands of pieces of clay pipes, wine bottles, and wine glasses.

The rectangular area of the sidewalk sectioned off by the railings will give you a glimpse of the Lovelace Tavern foundation walls that were unearthed. Under a nearby circular railing is a cistern, also unearthed through the digging, from a home of the Philipses, a family of wealthy merchants who had a residence built at 66 Pearl Street in 1689. The gray stone blocks in the sidewalk mark the limits of the Lovelace Tavern, while the lighter blocks mark the walls of the Stadt Huys, determined from seventeenth-century maps. The cream-colored blocks are supposed to represent yellow Dutch bricks, as can be seen on Fraunces Tavern. Now is a good time to take a look back at the street that you have been following, Pearl Street. Dutch maps indicate that this was the original boundary of the East River; the land that stretches beyond it to the water’s edge today is landfill. [archeology.org]

The good thing about doing multi-part pages is that I can leave off when getting tired. In Part 2: continuing up Pearl Street.

7/3/16

7 comments

Regarding your comment about Moore St. and there apparently not being any Moores for which it was named, I offer the following:

“The family seat on the Hudson was acquired by him partly by purchase from Charles Congreve, Esq., and partly by patent; his residence known as White Hall in later years, was at Moore and Front Streets, New York City. Note: This was NOT the home built before 1661 for the Hon. Peter Sturyvesant, last of the Dutch Governors. this house called Whitehall was near the Fort and burned to the ground ca 1719.” This quote taken from the Geni website, https://www.geni.com/people/Col-John-Moore/6000000009667510234. John Moore was my 4X grandfather. Thank you, GM

I am a descendant of the Coenradt Ten Eyck and enjoyed your writing thoroughly. Coenradt owned two house on the north side of Pearl St. , next west of Staat Huys Lane, which ran between it and the old City Hall. He owned several water lots oppostie, on the south side of Pearl Street and on the east side fo Coenties slip.

My husbands ancestor was a notary ( lawyer) from Holland. He was called for to help iron out differences in the French Indian War. He lived on Pearl Street…. maybe 6?? I’ve got to reread family papers.

As of August 2019, Herman Melville’s birthplace memorial at 17 State Street (6 Pearl Street) has disappeared — expunged by signage for “IP Soft,” a tenant of the office building. IP Soft describes itself on its website as a “disruptive technology company,” which seems accurate as far as Melville is concerned. Keith Haring’s “Two Dancing Figures” also has disappeared, replaced by a forgettable corporate logo.

What an amazing introduction to NYC history through a concrete example of a street. I will take a walk soon following the guidance of this article.

This is fascinating. My father owned the G & H Bar and Grill at 121 Pearl Street from 1940 to late 1950’s. Went there many times as a child and I was thrilled to discover this history, much of which he spoke of and I had forgotten. Thank you.

Would like to see the place where Captain Kidd and his wife Sarah Kidd resided at 119 Pearl St.. I’m reading the book ” The Pirates

Wife” The Remarkable True Story of Sarah Kidd”.

They lived across the street of the “Wall” barrier which was years later torn down and named Wall Street.