I’ve explored the 4th Avenue IND station at 9th Street in Park Slope before for Forgotten New York, way back in 1999 when the station was almost in ruins. Since then, the station has been cleaned up considerably, but repairs have been carried out only halfway; the project must have run out of money, and surprisingly, there’s been very little news about its completion, and I’ve seen no outcry about it from local residents or politicians. I’ve always been interested in this unusual elevated station and its partner, the Smith-9th Street station, the next station to the west, because they are the only two elevated stations the IND constructed in the 1930s.

One of my favorite subway websites is Vanshnookenraggen, the pseudonym of Andrew Lynch, who writes about a NYC subway system that never was, or one that never will be. Entries talk about subway lines that were never built; Lynch is also a cartographer, and produced detailed system maps of these “lost” systems. One was the IND Second System, which would have placed subways under 2nd Avenue in Manhattan, the northeast Bronx, southeast Queens, places they don’t go today and likely never will. Work actually got started, asome stations were built, but depression, war and new recessions happened; you know the rest.

Well, some sections of this Second System would have been elevated. What would an IND Elevated look like? For those unfamiliar with subway history, the IND was developed by NYC beginning in the 1920s to compete with the IRT (the number lines) and BMT (many of the letter lines) and had a much different design esthetic than the older lines; less ornamentation and mosaics, and a much more utilitarian look. It’s immediately apparent when you compare stations on the A/C/E and F lines, say, to the stations of the 4/5/6 train. As it happens, the 4th Avenue and Smith/9th Stations pointed the way to what prospective IND elevateds would have looked like–concrete-clad viaducts instead of iron pillars, for example.

The IND was built on two trunk lines in Manhattan on 6th and 8th Avenues, and forayed into the Bronx on the Grand Councourse, Queens on Queens Boulevard, and Brooklyn as far as Park Slope, where it originally ran as far as Church Avenue. Today’s A through G lines mostly run on tracks built for the Independent.

In 1940, the city purchased the IRT and BMT and “unified” the subway with the IND. Many more free transfers between lines were instituted, but it wasn’t really until two key connections between the BMT and IND were made at the Manhattan Bridge and in the East River tunnels in the 1960s that trains from the two old rivals could truly intermingle. Though there are plenty of free transfers to the IRT, because the cars and tunnels are narrower on the IRT (which was the “original” subway going back to 1904) there is no such intermingling of IRT cars on former BMT and IND lines to this day. True integration has never been accomplished.

The IND built just two elevated stations in Brooklyn in 1933, the tallest station in the system, Smith/9th (tall enough to let tall masted ships on the Gowanus Canal) to pass beneath it; and the Fourth Avenue station, lower because it is built just west of a tunnel entrance. There had been plans for the IND to build an elevated station that would connect the Roosevelt Avenue station in Queens with the Rockaways which would have been elevated in Glendale and Ridgewood, but the Depression and World War II canceled those plans; in 1956, the Transit Authority reached the Rockaways anyway by rehabbing a Long Island Rail Road trestle over Jamaica Bay that had burned in 1950, and then extending the A train over the former Fulton Street Elevated to meet it.

At the Fourth Avenue IND elevated station (opened July 1, 1933), the tracks are close to the ground, but still high enough to require bridging over the avenue. Engineers came up with a beautiful arch bridge with Art Deco accents. For the first few decades of its existence, the windows on the platforms were clear and allowed a view north to the Williamsburg Building and south toward Bay Ridge.

The windows on the arch bridge had been painted brown for many years, since at least the 1970s; I remember grime-caked windows you could see through as late as the Sixties. The MTA was tired of vandals graffiting and breaking them, so the agency just painted them opaque. Now and then, though, the paint flaked off and permitted a view.

For much of the last decade now the MTA has been rehabilitating the windows and has actually finished with the eastern set, but has installed an opaque covering on the windows, apparently so no one will think about breaking them. I’m not sure when, or if, the western set will reopen, and that set of windows remains covered by plywood.

Three of the original Art Deco-influenced pencil-shaped entrance signs remained in place through years of neglect, and were rehabilitated along with the rest of the station. Details on the arched bridge, as well as the brick viaduct between 3rd and 4th Avenues, also reflect Art Deco design elements.

If you’re not familiar with this area of Brooklyn, it may be a bit hard to believe, but the IND at this point quickly dives back underground, where it stays until it connects with the older Culver Line at Ditmas Avenue. The reason is geography: the land slopes sharply upward here (the Slope in Park Slope).

Why elevate two stations in the first place? It was considered more architecturally sound to elevate the subway over the then-busy Gowanus Canal rather than tunnel under it. As a product of that construction, the Smith-9th St. station is the highest elevated station in NYC, rising more than 87 feet above the street. It takes two escalators to get up and down.

Heading in, 4th Avenue reflects the overall IND design formula: off-white glazed brick tiling with simple color tile informational and directional signage. A little-known IND design element held that all IND stations between express stations were tiled the same color, with the color changing at an express station. This rule holds true even here on this elevated stretch, as the Bergen, Carroll, Smith-9th, and Fourth Avenue stations are all tiled in light green. The color changes to yellow at the “express” center-platformed 7th Avenue station, with following stations all tiled yellow until the “express” Church Avenue station, which is maroon.

I’ve placed “express” in quotation marks because the F and G lines, which run here, feature no express service and haven’t, with the exception of local platforms being closed for trackwork, for decades. Recently, the express tracks on the Culver Viaduct, to which this line connects, were in use while the Metropolitan Transit Authority rehabbed several stations.

Prior to the subway unification in 1940, there were free transfers between the IND and IRT/BMT, but they were doled out sparingly. The 4th Avenue Line, Brooklyn’s first subway, opened in 1915 and connected to the Manhattan Bridge, but ran to the Chambers Street station. The tracks were only later connected to the Broadway BMT.

The presence of a “Coney Island” tile sign, pointing to the southbound platform, at the 4th Avenue IND is a puzzlement. In 1933, when the station was built, the end of the line was at Church Avenue, and the line was only connected to the Culver Viaduct on McDonald Avenue in 1954. It’s possible that the city planned to build out this line to Coney Island from the jump, and created the signs in anticipation.

Subway historian Joe Brennan, in Comments:

A major purpose of the IND was to make company-owned elevated railways obsolete– consider Eighth Avenue, Sixth Avenue, Fulton Street, and planned routes like Second Avenue.

The “Coney Island” sign turned out to be very premature, but the IND plan from the start was to continue this route onto the “Culver” elevated over McDonald Avenue to Coney Island. The subway contracts had a provision to let the city “recapture” portions of route from the operating companies. Before 1940 the BMT company was operating the city-owned McDonald Avenue route from its company-owned old (1880s) Fifth Avenue El. The plan was to close that down and route the new subway onto the McDonald Avenue line instead. I do wonder where the Coney Island terminal was going to be, if the city had not bought out the entire BMT system.

The “B.M.T. subway” sign was not about a free transfer. If you changed trains there you paid another nickel. I think this passageway was one of the many free transfers created in 1948.

In the 1970s, the MTA hired a design firm called Unimark, and chief designer Massimo Vignelli, to standardize subway signage. After different colors and fonts were used for several years, black signs with white trim and Helvetica type were settled upon, and the MTA has been quite thorough, especially in the last 30 years, in rooting out earlier signage and sign designs, with many beautiful enamel signs in a variety of fonts and colors eliminated. In the IND, in many cases the MTA has left the simply-worded tile signs in place, but placed somewhat redundant modern signs next to them.

The northbound platform of the station has gotten, thus far, the deluxe treatment with the rehabbed panels. The windows are now glazed polyurethane and aren’t opaque, though they do allow sun rays to streak onto the platform. Combined with the metal “ribs” of the superstructure, the effect is unique in the entire subway system.

At sunset, the colors are diffused into works of art.

It has to be emphasized that the “panorama” only exists on a short stretch of the northbound platform. The rest of it is a brick wall with filled-in windows, which were also originally glass but the city decided to simply cover them over rather than constantly replace the glass after angry vandals continued to break them.

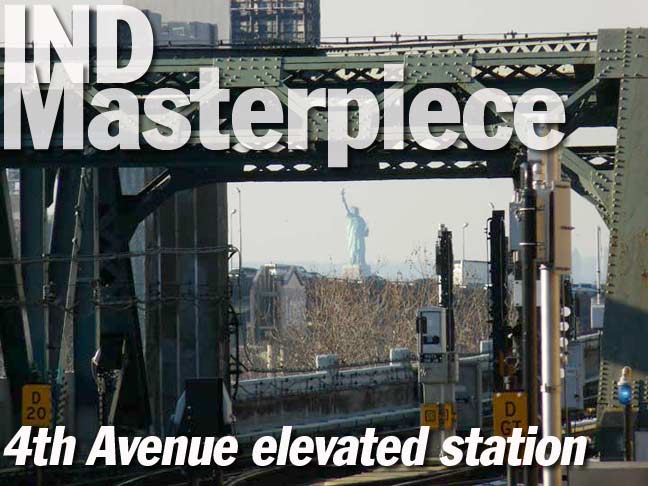

The Statue of Liberty can be clearly glimpsed from the west end of the platform, and through subway windows as it makes the curve on the viaduct west of the Smith-9th Street station. If you use a zoom lens you can obtain a good photo of the station through the ribs of the viaduct that spans 3rd Avenue.

The Fourth Avenue station is one of the subways’ unremarked-upon masterpieces. However, the city does not apparently have the money or the inclination to complete its excellent rehabilitation work to include the southbound set of picture windows over 4th Avenue, and that’s shame.

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

11/18/18

12 comments

A major purpose of the IND was to make company-owned elevated railways obsolete– consider Eighth Avenue, Sixth Avenue, Fulton Street, and planned routes like Second Avenue.

The “Coney Island” sign turned out to be very premature, but the IND plan from the start was to continue this route onto the “Culver” elevated over McDonald Avenue to Coney Island. The subway contracts had a provision to let the city “recapture” portions of route from the operating companies. Before 1940 the BMT company was operating the city-owned McDonald Avenue route from its company-owned old (1880s) Fifth Avenue El. The plan was to close that down and route the new subway onto the McDonald Avenue line instead. I do wonder where the Coney Island terminal was going to be, if the city had not bought out the entire BMT system.

The “B.M.T. subway” sign was not about a free transfer. If you changed trains there you paid another nickel. I think this passageway was one of the many free transfers created in 1948.

Thx for that info, I amended the article.

Two other stations need help, ASAP, in my opinion. They are:

Chambers Street (J,Z)

3rd Avenue (6)

Chambers Street (J/Z) is a magnificent dungeon, a dignified ruin, like Pompeii and Herculaneum. It’s a time capsule, loaded with relics and remnants from earlier times. The open side platform is a railfan icon, since its appearance is virtually unchanged from the station’s heyday. I would hate for the MTA to totally rehab this station and erase all of its prior glory. Id rather see a restoration, with the open platform refitted to its original glory and left in plain sight for all to enjoy.

I have a Contract Plan book of this station, it may be an original copy. I bought it from the TA at one of the Transit Museum Memorabilia Sales back in the late 80s/early 90s. I haven’t looked at it in years (it’s buried in the garage) but remember it had details of steel and concrete work, the tiling, the signs, the lighting, etc.

A description and depiction of the IND Station Tile Colors can be found here: https://www.nycsubway.org/wiki/IND_Station_Tile_Colors

Just a note. Back when the IND was being planned, the IRT used route names instead of numbers and the BMT had lines numbered 1 (Brighton) to 16 (Canarsie). The IRT got route numbers with the arrival if the R-12 cars in 1948. The BMT switched to letters with the R-27/R-30/R-30a in 1960, in anticipation of the opening of the Chrystie St Connection and merger with the IND. The letters chosen began where the IND left off. Also if you look at photos of R-16 cars, they display front route numbers when they ran on the BMT through most of the 1960s.

Thanks for the shout out! I take the train through here most of the week and have always been annoyed that they never took down the southern construction shed (not to mention the station still looks terrible but I assume they were more concerned with structural problems rather than aesthetic.)

Any way to find out whether they will ever resume rehabilitation of the south side?

The free transfer between the BMT and IND at 4th Ave was not opened until 1959. Prior to that you needed another token to change there.

I’ve noticed that the brick tiles used inside this station and Smith-9th are the large off-white and green tiles, a late 1940s-1950s design also seen in stations like Grant Av and 179th street. I suspect that this appeared during the reconfiguration for the free transfer as mentioned above, and prior to that, the tiles were the original IND designs since the stations opened in 1933, including the retained Manhattan/Coney Island tiled signs.

The platform walls of this station are brick but Smith-9th Sts are concrete I think. Knowing how uniform the IND likes to be and how the canopy beams are similar in both stations, they must both have had old IND tiles a well? Or maybe just the same brick. I wonder. I do love these stations though!

” However, the city does not apparently have the money or the inclination to complete its excellent rehabilitation…”

State runs the MTA, not the city. Have you bought Cuomo’s lies?

It seems to me that the colors change on the IND upon hitting the next express station out from West 4th.

Since the green stations are Bergen, Carroll, Smith-9th, and 4th, and then at express station 7th Ave they change to yellow with brown, I suggest that the express station beginning the green section is Bergen, which was built with (and has occasionally used) a lower level which comes from the 2 center tracks at 7th Ave. So it’s technically an express station.

I think I once went through Lower Bergen and it stopped there, in the 90s when I lived in Park Slope.

If I remember there was a coffee shop as you enter called Carway. Am I right?