In deep and dark November I took a walk straight up Mulberry Street for its entire length, which I had never previously done. It skirts the west edge of Chinatown and cleaves the heart of Little Italy, before ending at Bleecker Street, edging into the south end of NoHo. It’s one of three major north-south streets, along with Mott and Elizabeth, between Centre/Lafayette Streets and the Bowery. It’s teeming with street life with shoppers, tourists and residents and is among the most crowded real estate in New York City.

Little Italy originated in the 1880s, when immigrants from primarily, but not exclusively, Naples and Sicily arrived in New York City and settled in the streets between East Broadway and Houston and Centre/Lafayette Streets and the Bowery. After World War II there was an italian diaspora, as immigrants and their families moved to the outer boroughs and surrounding suburban areas, ultimately leaving a couple of blocks on Mulberry that still have a strong Italian flavor, chockablock with restaurants and coffee/pastry shops; tourism keeps these areas strong.

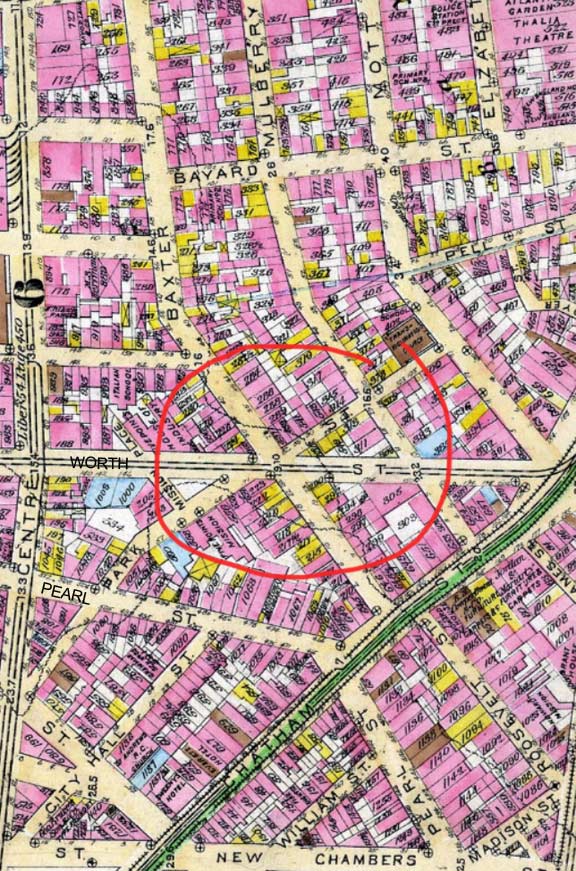

Today, Mulberry Street begins at Worth Street, but until the 1920s, it extended south one block further, to Park Row, indicated as Chatham Street on this 1885 map. Back then, Mulberry Street was the eastern end of Manhattan’s Five Points, so-called because its center was at the complicated intersection of Worth, Baxter (formerly Orange) and Park (now Mosco). From all accounts, it was a “most wretched hive of scum and villainy” as Obi-Wan Kenobi would say.

Five Points would by all accounts put the West 42nd Street of the 1970s and 1980s to shame for its collection of thieves, brigands, prostitutes, murderers and fiends. “The Deuce” of the 1970s’ 42nd Street had nothing on Five Points, which centered around a 1792 brewery on Cross Street near its intersection with Anthony and Orange Streets, at first known as Coulter’s Brewery, but by 1838 had become a rooming house known as the Old Brewery.

From Kenneth Dunshee’s 1952 account in As You Pass By:

The Old Brewery was a five-story building, old and dilapidated. Along one wall an alley led to a single large room in which more than seventy-five men and women of assorted nationalities and races lived together. This was the Den Of Thieves. The name was appropriate. Along the other wall ran another filthy lane called Murderer’s Alley worse than the first.

Upstairs there were about 75 other chambers, housing more than 1,000 people…men, women and children. The section was a warren, with underground passages and murderous cul-de-sacs, into which the police dared venture only in large numbers, for the Old Brewery for a period of more than fifteen years averaged a murder a night.

Five Points was too tough, too unlawful, too unsavory to last, even in the New York of a century ago. The Old Brewery was razed, the last of the gangs destroyed. Today it bears little resemblance to the bull-baiting, rip-roaring hell it was in 1850.

And from Charles Dickens in America: “Notes For General Circulation” (1842):

What place is this, to which the squalid street conducts us? A kind of square of leprous houses, some of which are attainable only by crazy wooden stairs without. What lies behind this tottering flight of steps? Let us go on again, and plunge into the Five Points. This is the place; these narrow ways diverging to the right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth. Such lives as are led here, bear the same fruit as elsewhere. The coarse and bloated faces at the doors have counterparts at home and all the world over. Debauchery has made the very houses prematurely old. See how the rotten beams are tumbling down, and how the patched and broken windows seem to scowl dimly, like eyes that have been hurt in drunken forays. Many of these pigs live here. Do they ever wonder why their masters walk upright instead of going on all fours, and why they talk instead of grunting?

By the 1920s, most of the vestiges of the old Five Points had been replaced by court houses, and by the 60s, high rise apartments had obliterated the last of its little wood frame and brick buildings. It’s a shame, though, that some of the buildings of this notorious slum couldn’t have been preserved in some way.

On the above map, most of the streets south of Worth have been wiped out, replaced by buildings like the Chatham Towers, the Daniel Patrick Moynihan US Courthouse, and the New York State Supreme Court Building. North of Worth, between Baxter and Mulberry, is…

…Columbus Park, which was built in 1887, replacing some of the old Five Points tenements. The expansive park was designed by Calvert Vaux, co-creator of Central and Prospect Parks. After going by a variety of other names, it was named Columbus Park in 1911 in honor of the many Italians settling nearby.

Mulberry Street was named on maps as early as the late 1700s and while surrounding streets like Mott, Elizabeth, Worth and Hester took their names from local personalities or war heroes, its moniker remembers groves of mulberry plants in the area when it was first laid out.

A one-block stretch of Mosco Street between Mulberry and Mott is all that remains of the formerly somewhat lengthy Park Street (originally Cross Street), which used to run from Centre and Duane Streets all the way northeast to Mott.

In 1982, the remaining stretch was named for community activist Frank Mosco, who was associated with the Church of the Transfiguration on Mott Street and involved himself with youth outreach, lower-income housing and the elderly, and organized the Two Bridges Little League.

I don’t want to get sidetracked on this odd little remnant — but will have some more information on a future page dedicated to it. I will say that the northeast corner, 100 Mosco, is where Frank Mosco himself lived, and 28 Mulberry, the current home of the Wah Wing Sang Funeral Home, began as the Banca Italia in 1888.

An aspect of Columbus Park, and other downtown parks such as Union Square, are their fairly large pavilion buildings, which allowed parkgoers some shade and shelter from the rain. I gather that for approximately 30 years beginning in 1980, after the pavilion had been overrun by homeless and drug addicts as well as pigeon droppings, the pavilion was shuttered until 2010, when it was renovated and reopened, this time with a ping-pong table, along with a coatroom and public bathrooms.

The pavilion, now with netting that does not allow pigeons to roost, affords interesting views south into Columbus Park and north along Bayard Street.

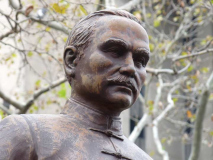

Who is that guy? Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (Sun Yixian) (1866-1925), the first president of the short-lived Republic of China, which ruled China after the Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911 and Japanese occupation during WWII and later, the Communist revolution of 1949. The statue, sculpted by Taiwanese sculptor Lu Chun-Hsiung, was erected in November 2011 to commemorate the centennial of the Republic’s foundation. It was originally meant to be a temporary installation, but later gained permanent status.

Interestingly the park lamps surrounding the pavilion have a Chinatown touch, a pair of dragon heads at the lamplighter’s ladder rest. There are other Chinatown-themed designs for NYC lampposts.

At #46 Mulberry, the date of construction is conveniently displayed at the roofline. I don’t know if the rearing horse is a longstanding or recent addition.

At #48, Mulberry takes a midblock northern angle, south of Bayard. This is the formerly infamous “Mulberry Bend,” a locus on the eastern end of Five Points as one of NYC’s worst neighborhoods, as described by photojournalist Jacob Riis in “How the Other Half Lives”:

Where Mulberry Street crooks like an elbow within hail of the old depravity of the Five Points, is “the Bend,” foul core of New York’s slums. Long years ago the cows coming home from the pasture trod a path over this hill. Echoes of tinkling bells linger there still, but they do not call up memories of green meadows and summer fields; they proclaim the home-coming of the rag-picker’s cart. In the memory of man the old cow-path has never been other than a vast human pig-sty. There is but one “Bend” in the world, and it is enough. The city authorities, moved by the angry protests of ten years of sanitary reform effort, have decided that it is too much and must come down. Another Paradise Park will take its place and let in sunlight and air to work such transformation as at the Five Points, around the corner of the next block. Never was change more urgently needed. Around “the Bend” cluster the bulk of the tenements that are stamped as altogether bad, even by the optimists of the Health Department. Incessant raids cannot keep down the crowds that make them their home. In the scores of back alleys, of stable lanes and hidden byways, of which the rent collector alone can keep track, they share such shelter as the ramshackle structures afford with every kind of abomination rifled from the dumps and ash-barrels of the city. Here, too, shunning the light, skulks the unclean beast of dishonest idleness. “The Bend” is the home of the tramp as well as the rag-picker.

Though this stretch can no longer be called a slum, a number of its buildings along the east side of Mulberry Street still stand.

This building, on the northeast corner of Mulberry and Bayard, is the former PS 23 — the first of over 100 buildings that schools architect Charles B.J. Snyder would construct in New York City. The school was dedicated in 1891, when the region was still trying to shake off its Five Points reputation. It was innovative as the first fireproof school building in NYC and featured a community center in the basement, also innovative for the time.

The rough-cut brownstone base featured arched doorways and carved medieval motifs. Above, the orange brick façade was broken by paired windows allowing fresh air and sunshine into the classrooms. The windows of the tower stair-stepped upwards following the course of the interior stairwell…

…The Evening World noted “Two advances, called by educators the greatest ever made, marked this structure. It was in this building that the first attempt at fire-proof construction for schools was made. The first floor had no inflammable materials.” [Daytonian in Manhattan]

Despite the building’s apparent inflammability a devastating fire in January 2020 so damaged the building’s top three floors (which may have been untreated) that demolition of much of the building was deemed necessary.

Hai Cang Trading, 71 Mulberry.

They may be eyesores, but these shops on the Chinatown-Little Italy border do bang-up tourist business selling shirts and trinkets.

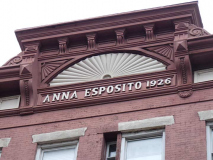

123-125 Mulberry Street, just south of Hester, is home to the Il Cortile restaurant, but I was drawn to the roofline, but I was drawn to #121, which displays “Anna Esposito 1926” on the cornice. The Esposito family was once prominent in Little Italy and I suspect, since this building looks older than it would be if it was built in 1926, that the date marks the birth of Anna. Older photos show the sign as rundown, so it’s been handsomely cleaned up in recent years.

I was drawn to #187 and 189 Hester Street, just east of Mulberry, which are both painted in the red, green and white tricolor found on the Italian flag. At left is Puglia Ristorante, which was the subject of a FNY guest post a few years ago.

I took a detour a block west to 136 Baxter Street at Hester. Readers of FNY may know I’m a fan of stolid brick buildings like this one, former factories or warehouses converted to condos. That happened at this building in 2007, which was named the Machinery Exchange since after its 1915 construction, it served as machinery storage as well as stables for police horses just south of the old NYPD headquarters on Centre Street, itself converted to residential in 1984.

The dome of the old NYPD HQ peeks above Baxter Street. The former NYC Police Headquarters, now Police Building Apartments at 240 Centre between Grand and Broome, and our Bishop Crook across the street at Centre and Grand, come from the same Beaux-Arts era from 1890 to about 1920. While not all Beaux-Arts buildings were public buildings, both of these structures embody the philosophy then espoused that our public buildings, and even our public utilities, should be beautiful; and so they are covered with ornamentation and even some archaic elements that modern-day architects would find wasteful and hardly cost-effective.

It’s hard to believe it, the HQ, constructed from 1905-1909, was empty and abandoned for about a decade from 1973-1983 after the new NYPD HQ in the Foley Square area was built.

Umberto’s Clam House, 132 Mulberry, relocated here awhile ago from its former outpost at the NW corner of Mulberry and Hester Streets. The restaurant gained infamy in its incarnation there when mobster Joey Gallo was shot dead there in 1972:

Joey Gallo had celebrated his 43rd birthday at the Copacabana nightclub with a group of arty friends that included the actor Jerry Orbach, comedian David Steinberg, and columnist Earl Wilson. The party finished and Gallo, his bodyguard, and four women went to Little Italy in downtown Manhattan, looking for a place to eat. The only restaurant open was Umberto’s Clam House on Mulberry Street, owned by the mobbed up Matthew ‘Matty the Horse’ Ianniello. Robert Daley, Deputy Police Commissioner, said the party ate ‘Italian delicacies.’ Gallo and his bodyguard, Pete Diapoulis, sat with their backs to the door. The assassin (from the Colombo mob family) put four bullets into Crazy Joey Gallo at about 5 a.m. Gallo staggered out the front door onto Mulberry Street, where he collapsed and died. Twenty shots were fired in all. The assassin escaped. Pete Diapoulas was wounded. He refused to talk to the police. The shooting left ‘Little Italy’ (the surrounding neighborhood) in an agitated state. Witness said they saw pistols in tenement windows. Deputy Commissioner Robert Dailey said, ‘He made a mistake, Crazy Joe did. He should have gone home to bed last night.’ Museum Planet

Note that “Crazy Joe,” who is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, had a lot of showbiz friends. The line between fame and notoriety can occasionally be blurred, and what’s right and wrong can sometimes be ignored. Bob Dylan eulogized him in a 1970s song.

There’s also an Umberto’s on Arthur Avenue in that borough’s Little Italy, and when I was a kid, I once had lunch with my mother in an Umberto’s branch at 86th Street and 16th Avenue in Bath Beach, Brooklyn.

At #138 Mulberry, the street makes another slight jog, though this Mulberry bend was far less notorious than the one further south. The pediment on the building marks an owner or architect, G.L. Jaeger. In 1884, German physician Gustav Jaeger was the inspiration for the British clothing line, but I doubt he had anything to do with this building.

Christmas New York is a year-round Christmas-themed shop at #142 Mulberry.

The small 2-story brick building with the pair of dormer windows at #149 Mulberry appears older than its neighbors, and indeed it is: it’s the oldest building on Mulberry save for Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral (see below). It was built in 1816 for NY state Assemblyman and Senator Stephen Van Rensselaer (1764-1839), who attained the rank of major general in the US Army before losing the Battle of Queenston Heights (which reversed US efforts to invade Canada) during the War of 1812.

After moving into the house, Van Rensselaer served on the New York State Constitutional Convention, the Erie Canal Commission, and the US House of Representatives. He amassed a fortune of $10M, worth multibillions in 2018 money. His family owned sprawling estates in New York and plenty of NYC properties, and this modest building was not his primary residence. In 1842, the house was moved from the corner of Mulberry and Grand to its present location. When the environs became Little Italy, the wealthy Stokes family acquired it and turned it into “The Free Italian Library and Reading-Rooms” in 1894.

The building has hosted a succession of restaurants and other businesses over the decades, at present the Aunt Jake’s trattoria.

The Piemonte Ravioli Company was established in 1920 by an immigrant from Genoa. In 1955 Mario Bertorelli from Parma took over the store, which he and his son, Flavio, continue to operate. They array a full line of fresh pasta which they make daily in their warehouse in Woodside. The variety of pastas include: ravioli, tortellini, manicotti, cannelloni, stuffed shells, gnocchi, cavetelli, linguine, fettucini, lasagna. Homemade and dried pastas fill the racks from end to end. The pastas are stuffed with everything from spinach and cheese to seafood, meats, and vegetables. [Place Matters]

Piemonte has two entrances on Mulberry and Grand Streets, interrupted by Alleva on the corner. Both shops feature signage in the Italian flag tricolor. Both 190 and 192 Grand Street were also constructed by Stephen Van Rensselaer, both buildings in 1833 in the popular Federal style of the early 1800s.

Pretty much the epicenter of Little Italy is the corner of Broome and Mulberry, with two of its ancient bastions, Caffé Roma and Grotta Azzurra. Caffé Roma has two old signs, a classic neon and a constantly renewed and repainted building ad, one spelled the Italian way and one in English.

Traditionally Mulberry and Broome were Neapolitan territory. In the early 20th Century the Ronca brotehrs from Naples opened a cappuccino, espresso and Italian pastry shop on this corner. The Roncas sold to Vincento Zeccardi in 1952, who renamed it but kept it close to the old Ronca name. His descendants (some of whom were “connected”) continue to run Caffé Roma, maintaining original elements of the place such as a saloon clock over the espresso machine, dark green pressed tin ceiling, and handwritten recipe book. Directly across the street was Umberto’s Clam House, now the Crudo Oyster Bar. Mobster Joey Gallo breathed his last at Umberto’s when it was located nearby on Mulberry Street.

The original Grotta Azzurra (“Blue Grotto”), named for a picturesque sea cave in Capri, opened in 1908 and lasted until 1997, serving fare to the likes of Enrico Caruso and later on, Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack. The restaurant reopened in 2003.

I don’t know much about the magnificent corner building, #390 Broome Street at Mulberry. I can say that until the early 1970s, when SoHo was more manufacturing and industrial in character, there was a real possibility that Broome Street would have been shadowed by an elevated expressway, the Lower Manhattan or Lomex, which would have connected the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges with the Holland Tunnel, but traffic czar Robert Moses’s plan was thwarted. (I wonder if a tunnel is feasible, since the Canal Street traffic is miserable.)

Since I am both a Philistine and have the culinary tastes of a 12-year-old, I’ll skip the clam pizza that Pasquale Jones at Mulberry and Kenmare is renowned for, but don’t let me stop you. I did dig the retro neon sign, which has the curves and proportions of other classic shingle neon signs that have mostly disappeared from the NYC-scape.

On the southeast corner here’s 188 Mulberry on the corner of Kenmare, which is sort of magnificent in its sooted glory; it seems to have not gotten the power-washing that a lot of area buildings have received. On the ground floor is Mulberry Iconic Magazines. I didn’t have my backpack with me, but if I had I may have wandered in to see if they had this month’s Mojo, a British classic rock magazine.

#205 Mulberry is the former NYPD 14th Precinct House, long converted to condominiums and retail. It was built in 1871 and has French Second Empire characteristics such as a slanted roof with dormer windows. The architectural style was popular in the 1870s and 1880s.

Spring Lounge, at the SW corner of Mulberry and Spring Street, has been around since the speakeasy days of the 1920s, despite what the sign says, at first surreptitiously dispensing beer in growlers. It has operated under a variety of names since then such as Chappy’s and Wilson’s 10:30, but has been the Spring Lounge since the 1970s. It attracts interesting neighborhood denizens. “You find this place, get on the sauce and suddenly one quick beer turns into 11 or 12…”

After years as an empty lot, this odd, incongruous building at #47 Prince at the NW corner of Mulberry, designed by hotels architect Gene Kaufman, finally went up in 2016. It was briefly home to the Miss Paradis restaurant.

The McNally-Jackson independent bookstore, on Prince just west of Mulberry, is always a look-in when I’m in the area. They’ve always been seemingly resistant to the charms of Forgotten New York the Book, though, since for 11 years I’ve never found it in the NYC section!

St. Patrick’s “old” Cathedral, 260-264 Mulberry Street between Price and East Houston, is called “old” to differentiate it from its “newer” cousin uptown, St. Patrick’s Cathedral at 5th Avenue and East 50th, designed by James Renwick Jr., opened 1878 and finished in 1888. Old St. Pat’s, NYC’s original Catholic cathedral, is quite a bit older, having started construction in 1809 and completed in 1815, making it one of the oldest buildings in Chinatown/Little Italy. In March 2010 Pope Benedict XVI announced that it would become Manhattan’s first basilica, a church that has been accorded certain specific and ceremonial rites only the Pope can bestow.

In 2010, FNY did a post on the church, so if you’re curious, I’ll direct you there.

Though the churchyard and its graves are gated off and inaccessible, I did manage a few shots over the gates. Among the burials are the Venerable Pierre Toussaint and Stephen Jumel, whose uptown mansion in Sugar Hill is Manhattan’s oldest remaining private residence. The catacombs are occasionally open to the public.

“Dagger John” Hughes, the first Archbishop of the Diocese of New York, was originally interred in the Old St. Patrick’s churchyard. Though his remains were moved uptown to the “new” St. Patrick’s at 5th Avenue, he is memorialized here. “He became known as ‘Dagger John,’ both for his following the Catholic practice wherein a bishop precedes his signature with a cross, as well as for his aggressive personality.”

For some interior views of Old St. Patrick’s, see the Newtown Pentacle.

#263 Mulberry, across the street from Old St. Patrick’s, is the parish rectory, or priests’ residence. It was built in the mid-1840s, while John Hughes was still the Archbishop; the Second Empire-style mansard roof was likely added in the 1870s.

Tiny Jersey Street is wedged between the New York Public Library Mulberry Branch building and the Puck Building (see below). the alley runs for two blocks, crossing Lafayette before ending at Crosby.

Most of Manhattan’s obscurer alleys, from Extra Place to Cortlandt Alley to Staple Street are aligned north-south against the grid. Jersey Street unusually runs east to west, from Mulberry across Lafayette, ending at Crosby. It was apparently laid out as early as the 1820s and for a short time was called Columbian Alley (a poetic name for the USA is Columbia, for the sailor of the ocean blue in 1492). In 1829, the name was changed to Jersey Street — perhaps one of the neighbors was from the English Channel island of the same name.

The famed Puck Building takes up the entire block between Lafayette, Mulberry, the alley Jersey Street and East Houston. It was built as a printing plant between 1886 and 1893 by the publishers of the satirical magazine published between 1877 and 1918. It has recently been home to both the New York Press weekly and Spy monthly, though both left the building before going out of business (I write for New York Press’ online successor, SpliceToday). Some of the Puck Building was shaved off when Lafayette Street was extended south.

I had never noticed it before, but what is that thing on the Puck Building on the corner, just below the top floor?

One block of Mulberry Street edges into NoHo above East Houston, before succumbing at Bleecker Street.

A look at one of the Bleecker Street IRT #6 train station’s gorgeous wall plaques, before heading to further adventures.

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

12/16/18

18 comments

In Five Points, Park isn’t todays Mosco, Todays Mosco if north of Worth a little bit.

disregard, I was looking at the map wrong.

The joke going around after Crazy Joe was whacked was: “He shoulda gone to Vincent’s”. (Vincent’s Clam Bar was across Mulberry Street.)

One of my ancestors – Archibald Gatfield – owned a house on Mulberry in the 1780s. Mulberry was better known “Slaughterhouse St” during that period.

Memories of the lat 1970s when we were installing the electronic publishing system at the Daily News.

Once a month we’d go downtown for Peking duck and then walk over to get expresso and a sambucca with coffee beans.

By coincidence, was working at the news the day they were filming Superman.

Oh yes, we did similarly have dinner at a place on Doyers St. (King Wu?) or somewhere else in Chinatown and then walk over to Ferrara’s bakery for espresso and cannolis. Chinatown and Italy were entwined.

Anna Esposito was the wife of Salvatore Esposito. Mr Esposito purchase the land to build the front building from the Rensselaer family.

Really cool to read all of this, I just moved into the Anna Esposito building. If anyone has a recommendation for a good book to get a full history of this area during this time I would love to know!

Really interesting to read about this, I just moved into the Anna Esposito building on Mulberry. So much history in this area!

The group floor was once Lucky Luciano’s social club and hangout for mobsters.

Was not during 1988 to 1989 the Italian restaurant named “Cafe 121” located at 121 Mulberry St., aka Anna Esposito building?

Umberto Ianello had a brother that sold printing equipment in Little Italy, does anyone remember his name?

I would like to know why the numerationof Mulberry St. starts with number 20 rather than one?

Anyone knows?

PatrioticsUSA@aol.com

Mulberry once extended further south.

My grandpa is booked in Ellis Island in 1912 as staying in 72 Mulberrry St., however at 72 Mulberry st. by 1891 there already was PS 23

I heard that Mulberry St. numeration had changed, anybody knows anything about it?

PatrioticsUSA@aol.com

My great uncle live on Mulberry when he migrated from Italy. Truly fascinating history of NYC.

What Buildings were standing where Chatham Towers Stands Now ? The elevated train?

The families of my great grandmother lived at 27 Mulberry in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Their names were Merello and Volta. Carlo and Dominica Merello and Lida Volta. My sister and I are

looking to fill in some family history for my sons and grandchildren. When I was a little child, my father would drive by and stop on Mott Street to buy Leche nuts. All relatives from a bygone era

are gone. Families are buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn. Many stories about my great aunt Rose Merello Guarino are online. She was murdered at the Merello summer home in

Midvale. Family moved to Brooklyn in early 1900s.