It all began with a strange (to me) map notation on a Geographia Hudson County atlas, specifically, in Jersey City at Wayne and Monmouth Streets just west of downtown. “Dixon Crucible” it read, and I was drawn there just to see what this was all about.

A crucible is a vessel made of a refractory substance such as graphite or porcelain, used for melting and calcining materials at high temperatures, but it has a broader meaning as a severe test, or a situation or place that severely tests all those that experience it, such as the Depression or my tenure at the World’s Biggest Store. That meaning of the word may or may not have been helped along by Arthur Miller’s Cold War era play.

It turns out that “Dixon Crucible” turns out to be an incredibly handsome collection of brick buildings in a Romanesque style that used to be the world headquarters of one of the worlds’ largest pencil companies, Dixon Ticonderoga. In 1827, Marblehead, MA native Joseph Dixon (1799-1869) went into business manufacturing crucibles, which employ lead and graphite, and early on developed writing tools that employed the dark-colored, lightly greasy substance. Pencils began to oust the quill pen as affordable writing implements during the Civil War era, and Dixon Ticonderoga, its pencils with the familiar yellow color and green metal bands above the eraser, became along with Eberhard Faber the leaders in American pencil manufacturing. By 1871 the company was producing 86,000 5-cent pencils per day.

Dixon didn’t concentrate on strictly pencils, however; he created graphite stove polish, fast-color dyes, developed an early form of photolithography, and even produced steel at the cluster of buildings seen on this page, which were built between 1845 and 1850 along Wayne Street, Monmouth Street, and what is now Christopher Columbus Boulevard. The building seen above was home to the company’s offices.

Closeup of the arched windows on the Monmouth Street side, showing its incredible detail.

Corner of Wayne (foreground) and Monmouth, showing two pedestrian bridges connecting the complex.

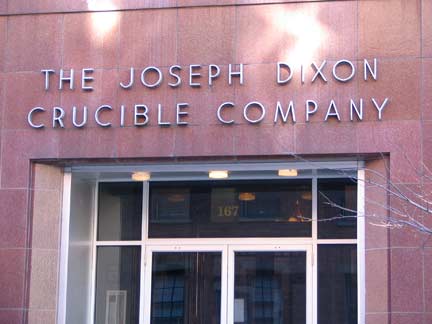

The front of the complex was given an incongruous Moderne front entrance in the 1940s, but that in itself has attained classic status over the decades.

Dixon Ticonderoga, now located near Orlando, Florida, sold its Jersey City locale in 1986 and it was converted to a mixed use complex of 452 apartments, retail units, and a health club, known as Dixon Mills. Jersey City Architect James N. Lindemon did a creditable job preserving the complex’ 19th-Century touches, and even added a couple elements faithful to the spirit of the complex when it was one of America’s leading manufacturers.

The painted green, black and white signs, for example, are faithful to 19th Century style. The Monmouth St. nameplate is the original.

Other old and new touches are the radial-wave luminaired streetlamps and the wonderful pedestrian bridges.

The other buildings in the complex are not as fancy as the Romanesque office building — just good old solid brick construction and an unbroken line of windows. I love architecture like this (I’ve never lived in a building other than a brick building and probably never will) — it just looks impregnable, solid, timeless, and indestructible. This is the NE corner of Monmouth and Columbus. Note the new retro-style sign on the Columbis side, and the McCoy, faded but hanging in there, on the Monmouth side.

A closer look at the Monmouth Street faded sign, and another on the Columbus side, showing the Dixon logo.

I’ve been forever intrigued by factories that have been converted to residences, and high-end or not, I’m happy with what Dixon Mills has done here.

4/16/08