There are many American Streets in Philadelphia. Or, strictly speaking, there’s one American Street in about twenty different pieces…

William Penn‘s and Thomas Holme‘s original Philadelphia grid pattern, developed in the 1680s, has proven to be a major influence on city plans across the United States; Manhattan’s grid pattern owes a debt to it, and Queens adopted the Philly numbering system in the 1810s with lower numbers near the river, getting larger the further inland you go. In the 325 years since the plan was first adopted, though, Philly has acquired one of the most maddeningly complex street systems possible in a basic grid.

Between each numbered north-south street it’s possible to have up to three interstitial streets, many of which are no more than alleys. The same holds for the named east-west streets. Rarely do all three streets turn up, though, and usually only one or two appear, running for only a block or two. Thus, these streets go on for miles, even though they are broken up and one piece can appear, say, in South Philly and only again in Olney or Fern Rock.

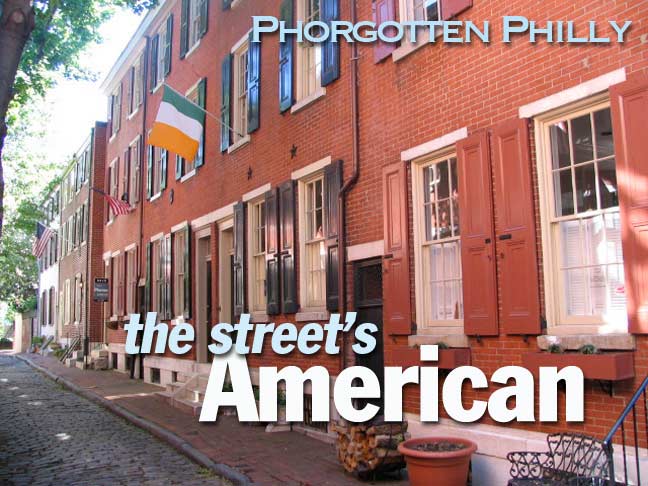

One of these slight lanes is American Street, which is a thin, bricked alley in some neighborhoods, and covered by a freight line in others.

The situation came about in 1854 when several townships and locales were absorbed by Philly proper. To avoid duplication of street names, it was decided to adopt a single name for streets that were in the same spot N-S and E-W.

Prior to the late 1800s, American Street was known, in different spots, as Corn, Strongford, Guilford, Aberdeen, Levant, St. John, and Washington Streets, as well as Ashland between Delancey and Spruce, as shown by the chiseled sign shown here at Delancey and American.

The lightpost nearby, though, display’s the street’s present name.

Here, American Street is typical of so many lanes in Old City, Society Hill, and Queen Village: narrow, Belgian-blocked, and lined with cozy townhouses, many of which still have wood-burning fireplaces.

But glancing down the street I spotted a noticeable difference…many of the homes were displaying unusual flags.

Here’s the 15-star-and striped American flag, in use between 1795 and 1818, adopted when Vermont and Kentucky became states. This was the configuration that was flying at Fort McHenry, MD in the War of 1812, inspiring Francis Scott Key to write the Star-Spangled Banner. In 1818, Congress passed legislation dictating that a star should be added to the flag when a state was admitted, but stars and stripes should be fixed at 13, denoting the 13 original states.Key’s flag is displayed at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

Here’s the An Bhratach Náisiúnta, the flag of the Irish Republic, adopted in 1919 during Ireland’s war of independence from Great Britain. The green on the left, or coming first, represents Irish Catholics, the orange on the right the minority Protestants (for William of Orange) and the white, the truce between the two.

Oddly enough, the flag of the Ivory Coast reverses the colors, with orange on the left, white in the middle, and green on the right.

This flag is the official banner of the Philadelphia Light Horse Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry, a division of the PA. National Guard. It was one of the first patriotic military divisions established (1774) during the American Revolution; the troop fought battles at Trenton, Princeton, Brandywine, and Germantown and served as General Washington’s personal bodyguard; during the Civil War, it fought at Bull Run and Gettysburg. It last deployed overseas in Bosnian conflict in 2003.

The British Union Jack was originally painted in the canton (the corner field) but the artist was instructed to paint thirteen stripes to represent the united colonies; this was the first flag to thus represent the colonies.

This red and gold banner, with lion rampant (standing on the left leg with paws raised) is the Royal Banner of Scotland (not to be confused with the Flag of Scotland featuring St. Andrew’s Cross) and was the national flag of Scotland before its absorption into the United Kingdom in 1707. It is still raised at Scottish royal residences when the British monarch is not present. Many Scots still proudly display it.

The flag is described in heraldic terms as: “Or, a lion rampant Gules armed and langued Azure within a double tressure flory counter-flory Gules.” (a yellow field with a lion rampant with blue tongue and claws within a double-ruled box ornamented with fleurs-de-lis.) The lion is sometimes shown, as here, without the blue in the tongue and claws.

6/9/08