When NYC had a more rural character and was dotted with farms a couple of centuries ago, grist mills, in which grain is ground into flour, were primary engines of commerce. Though none are left within the five boroughs, maps nonetheless are stocked with lanes and roads called Mill, some major, some minor — Manhattan (1), Brooklyn (5, no less) and Staten Island (3) all have Mills or Old Mills in them, and all likely led, at one time, to actual mills — most are near the water. I was recently ambling genially down car-choked Cropsey Avenue in Bath Beach, Brooklyn (the subject of a future FNY page) when I happened upon a time machine that brought me back to the rural Kings County of the mid-1800s.

Brooklyn and Kings County were not always one and the same. The town of Brooklyn once clustered around the downtown section and Brooklyn Heights; in the 17th Century Dutch and English settlers founded what eventually became the six towns of the county: Brooklyn (Breukelen), Bushwick, Flatbush, Flatlands, Gravesend, New Utrecht and New Lots. Brooklyn, the dominant town, incorporated as a city in 1855 and gradually annexed the other towns so that, by 1894, the city of Brooklyn encompassed Kings County — only to consolidate with Greater New York in 1898.

The original town of Gravesend was first settled in 1643, making it not only the oldest settlement in Brooklyn, but the oldest in Long Island, and the original town’s square shape has never been compromised as Brooklyn grew up around it. Dutch provincial governor of New Netherland William Kieft donated a small tract of land in what became Gravesend to a British immigrant, Lady Deborah Moody, and her son, Sir Henry, in 1643.

Amazingly the square town plan of Gravesend has survived the imposition of Brooklyn’s street grid surrounding it, much as Jersey City’s Bergen Square has. And, even though seemingly more of Gravesend’s historic buildings are erased ever year, some of the old roads of Gravesend, such as Lake Place and our subject today, Mill Road, are still in place.

Villages of Gravesend

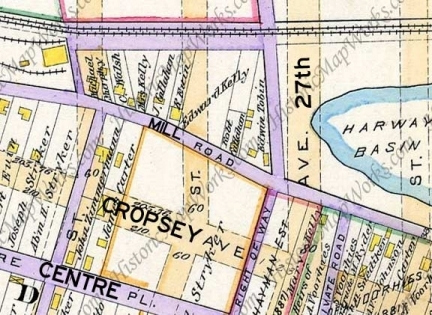

This 1873 Beers atlas plate shows the villages of Unionville and Guntherville that year. The present location is the Bath Beach section of Brooklyn, along Cropsey Avenue between about 25th and 28th Avenues, none of which was mapped out at the time.

Of the 7,000 acres of land in the original Gravesend, 3,500 were farm land, 300 woodland, and the balance salt meadows and a ridge of sandhills near the seashore. Directly opposite Gravesend, on the other side of Lower New York Bay, are the Navesink Highlands; along these highlands and the Navesink River the sand is of a reddish color, hence the name of Red Bank in the neighborhood. On the Long Island shore the sand is of a grayish color and this fact may have led the settlers to name the shore “Granuwezande” or Grauesand, as the name is often written in the old documents, i.e.,”Grayishsand.” The Dutch Church was organized in 1763 and a church edifice was erected, which was replaced by a second one in 1833, and this one again by a third in 1894. Shortly after the conquest the town was made the seat of justice, a courthouse was erected, and the Courts of Session of the West Riding were held there.

In 1810 Gravesend village contained twenty houses, the Reformed Dutch Church and a schoolhouse. A lighthouse was designed to be erected at Coney Island. There were two tidemills. The taxable property was valued at $178,477. The population was 520, which rose to 810 in 1840. The settlement in Sheepshead Bay was originally known as “The Cove” and later as Sheepshead Bay. Other neighborhoods were Unionville and Guntherville, on Gravesend Bay, South Greenfield on the King’s Highway, and on the head of Gerrettsen’s Creek, extending over the Flatlands line. Hopefarm.com

The map shows Mill Road issuing southeast from the right of way of the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad (it is the road just south of the hatched line designating the railroad). The BB&CI was the first steam railroad in Kings County and was organized by Charles G. Gunther, the mayor of NYC (which then encompassed Manhattan only) from 1864-1866. The railroad originated at 5th Avenue and 25th Street –then as now the main entrance to Green-Wood Cemetery — and ran southwest, south and southeast to Coney Island. Gunther was forced to build a roundabout route to avoid landowners’ (mostly farmers at the time) opposition. A second steam RR to Canarsie was founded in 1865, and Andrew N. Culver’s straighter, and therefore more successful, steam railroad, was founded in 1875. All three of these steam railroad lines, with some changes in routes, were succeeded by elevated and subway lines.

Guntherville was likely named for Charles G. Gunther, who owned property in the area (note the “C.G. Gunther” south of Mill Road in the center of the map). The name was favored for only a few years, however, and the town was absorbed into Bath Beach after landfill joined it to the rest of the area.

Another section of the 1873 Beers atlas gives a more general look at the lay of the land as it was back then. Today’s Bath Beach neighborhood is built on considerable landfill. In that era, creeks large and small infiltrated what is today bone-dry, and the land was marshy and little-populated. Hubbards Creek wound through Bath Beach in 1873, and the unmarked Harway Basin cut off a small spit of land at left. Mill Road was the main route to get to this narrow peninsula. I have marked the current crossroads of Mill Road and 27th Avenue to demonstrate how different the modern map is from this.

Elsewhere in Gravesend, the quadrangle at Gravesend (McDonald) Avenue and Village Roads North and South was there in 1873 and was already two centuries old. 86th Street was a line on the map, but was on the planning boards and would be a major route within 10 years. The creeks and inlets would be filled in.

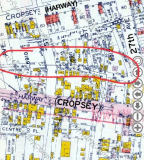

On an atlas from a few years later, we see the grid of planned streets in the region, though few of these streets were likely built yet. Both Harway Basin (the blob of blue east of the peninsula) and Hubbard’s Creek continued to wind through the marshy land. Coney Island Creek, beginning just south of the big “Y”, wound east into Sheepshead Bay. This connection would be landfilled out of existence in the 1920s. Already the name “Guntherville” has gone out of favor.

Just one legacy of the peninsula remains on the present-day map. Cropsey Avenue begins a major turn to the southeast at 24th Avenue and then south to Coney Island. The reason it does this is plain from the map: it curves to traverse the long-lost peninsula, all those years ago as Harway Avenue. Cropsey and Harway Avenues traded names at some point in the 1930s.

The Canal Avenue shown on the map still exists in two tiny sections about 20 blocks apart. One of the abiding Coney Island mysteries for me is why West 18th, 26th and 34th Streets were skipped over on the Coney Island peninsula, but this map indicates that it goes back to the drafting stages.

If we move our time machine to 1890, we see a small community called Gravesend Beach in the place of Guntherville. Purple roads are those already in place, while planned streets are shown in brown. Mill Road ran from Cropsey Avenue, at the northwest extremity of the map, to a dead end on the old peninsula separated from the mainland by Harway Basin. A few north-south lanes, such as Stryker and Hubbard Streets, ran to Gravesend Bay. There was a short parallelling lane, Centre Place. The small yellow boxes are houses. The BB&CI railroad is still plying its old route, and would do so until 1917-1920 when the el familiar to us now was built on 86th Street and Stillwell Avenue.

I zoomed in on the section surrounding Mill Road and 27th Avenue, which was not yet built in 1890, but was on the drafting boards, and added present-day place names. Note the purple line going north from Mill Road just west of 27th Avenue. If you return to the 1873 map above, it’s shown there as well; it served to connect Mill Road and the Gravesend town village quadrangle. It has been called the Road to Gravesend Village and in its final decades, Beach Lane. The easternmost section is still there, as Lake Place.

By 1929 (left) Hubbard and Stryker Streets still existed, and had houses on them (they are just to the west of what is shown here) but the street grid we know today was beginning to be cut through. Many of the houses on the older lanes were moved to the newer ones, such as Bay 43rd and 44th Streets. I have circled Mill Road at the section of it that still exists today. You can see a number of yellow boxes indicating homes. RIGHT: 1949 Hagstrom map. Mill Road is shown pretty much as it exists in 2010. West of the Belt Parkway, vestigial remnants of Hubbard Street and Centre Place are shown. This space is now occupied by Calvert Vaux Park; the great urban planner and architect drowned in Gravesend Bay in 1897. The BB&CI right of way was used by trolleys at this time.

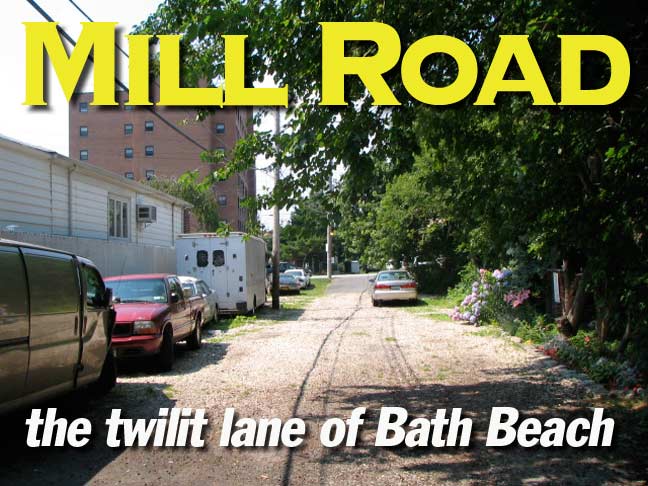

Mill Road today

Two blocks of Mill Road survive today, running from Bay 43rd Street south to 27th Avenue. Looking south from Bay 43rd, Mill Road is weed and grass covered, without any property fronting on it. The section facing Bay 44th has a short paved section that serves as a small parking lot for the Sons of Italy Senior Housing, which fronts on Cropsey Avenue.

Mill Road from Bay 43rd, looking south toward 27th Avenue. Oddly, while the city has telephone wires strung on poles with standard streetlamps attached, the Department of Transportation does not mark Mill Lane at all, meaning it’s not on official city directories. Therefore area residents have designed a makeshift method of identifying the road.

A pair of Mill Road homes. Most of the homes are on the north side of the street, with the south side used for parking and stashing wrecks, like his truck.

The cottage on the left — perhaps better visible in winter (I didn’t want to get any closer since I have found southern Brooklyn residents to be secretive about their properties) is perhaps the most unchanged of any of Mill Road homes. A long-disused cottage is next door.

While this block of Mill Road is asphalt paved most of its length, there is a short unpaved middle section that has been covered with small pebbles. A bungalow at 27th Avenue is heavily aluminum sided.

Mill Road, looking northwest; the senior housing is on the left. The picket-fenced bungalow has another makeshift sign attached to the tree.

Mill Road seen from 27th Avenue. A major road to the Gravesend village center once ran from Mill Road on the right side of the photo.