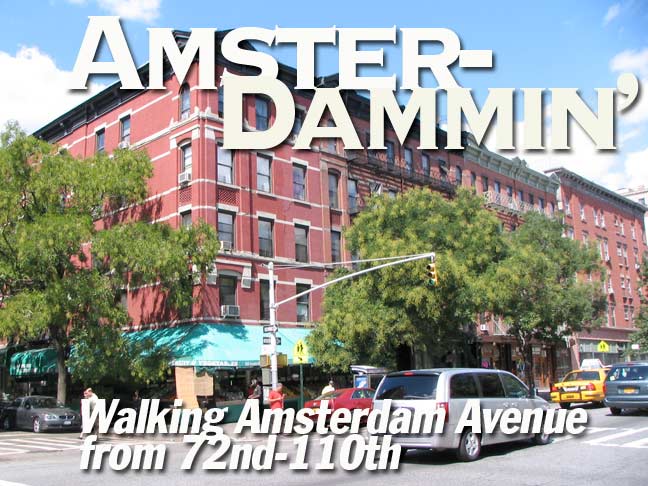

If there is a glaring weakness in the FNY canon it’s upper Manhattan. For whatever reason I have not spent enough time north of Grand Army Plaza or Columbus Circle. To rectify things somewhat, I meandered up Amsterdam Avenue from Verdi Square to Cathedral Parkway in August 2010 and then wavered down 116th Street from Riverside Drive to the new Target center the same month, and the fruits of that labor will soon appear here. A walk up St. Nicholas Avenue from West 110th to Dyckman Street is also a possibility soon. There are entire worlds in Harlem to be explored more fully.

If you consider it together with 10th Avenue, Amsterdam Avenue is the lengthiest north-south roadway on Manhattan Island other than Broadway. Due to Manhattan’s topography, 10th Avenue begins at West Street and the Hudson River and runs straight, with no curves or bends whatever, to Fort George Avenue and High Bridge Park just a short way from the Harlem River on the island’s east side. The roadway was mapped as 10th Avenue in the 1810s, with the stretch north of West 59th renamed Amsterdam Avenue in 1890, though a short stretch of 10th Avenue can be found in Inwood, way uptown.

The renaming was done to honor NYC’s connection with Holland, in which Amsterdam is the largest city and the capital. It was founded in the 12th Century as a dam in the river Amstel, from which it was named. If you believe the Amstel Light beer commercials, you’re never far away from a good time there.

I arrived at the 72nd Street station of the Broadway IRT, which has boasted a classic station house since its construction in 1904 (the post card at right dates from shortly after, and even then the Ansonia (see below) dominated the scene. It’s one of the original 28 NYC subway stations. It had always been the oddest of the express stops since, like 34th Street on both the IND and IRT stations, it was built in such a way to make a cross platform transfer from uptown to downtown trains impossible. This situation was alleviated by the construction of a new stationhouse in 2002, which, with its glass ceiling and panes on either end, has a European, airy design. Look at it on either side, though, and it’s nothing to write home to mother about.

The triangle formed by Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue and west 73rd street is Verdi Square, named for famed composer Giuseppi Verdi (1813-1901) whose operas Aida, La Traviata and Rigoletto, and many others, have been continuously performed since they were written. The Verdi monument was sculpted by Pasquale Civiletti and installed in the square in 1906. The four figures at the base of the statue are four of Verdi’s operas’ most enduring characters: Falstaff; Leonora; Aida; and Othello.

Right: The Ansonia was constructed between 1900-1904 and opened in 1904, along with the subway. Architect Paul Duboy based its design on the grand apartment buildings found in Paris at the turn of the 20th Century. It was named for the Connecticut town where developer William Earle Dodge Stokes’ grandfather, Anson Greene Phillips, founded the Ansonia Brass and Copper Company.

“It looks like a baroque palace from Prague or Munich enlarged a hundred times, with towers, domes, huge swells of metal gone green from exposure, iron fretwork and festoons. Black television antennae are densely planted on its round summits. Under the changes of weather it may look like marble or sea water, black as slate in the fog, white as tufa in sunlight,” observed novelist Saul Bellow in his 1956 book, “Seize The Day.” The City Review

“The apartments were sumptuous, many with oval or circular rooms giving panoramic views over the city. Standard furnishings included specially woven Persian carpets, ivy-patterned ‘art glass’ windows, and domed chandeliers inset with mosaic. There was a Grand Ballroom and several cafés, tea rooms, and writing rooms, a lobby fountain filled with live seals, a palm court, a Turkish bath, and the world’s largest indoor swimming pool.” Peter Salwen, quoted in The City Review linked above.

Immediately north of Verdi Square on West 73rd between Broadway and Amsterdam is the former Central Savings Bank, now Apple Bank for Savings. The bank was established in 1859 (as the Roman numerals indicate) as the German Savings Bank and became Apple Bank in 1983. Architects York and Sawyer fashioned the building in 1926 as a mini-Federal Reserve Bank of New York, a building the architects had designed 6 years previously, where 30% of the world’s gold reserves are stored in a basement built into the bedrock.

RIGHT: looking north on Amsterdam Avenue. In the center is a building marked Hotel Lincoln, which perplexes me because the only Hotel Lincoln in Manhattan I was aware of was on 8th Avenue between West 44th and 45th, which hosted big band concerts in the 1940s; it became the old Milford Plaza, which had unforgettable TV ads.

At the northwest corner of Amsterdam Avenue and West 75th Street is this 1889 building originally a stables and then The New York Cab Company, and latterly a parking garage. Blocks between 75th and 77th and Amsterdam and Broadway became a livery district known as Stable Row around 1900; this is one of the few that remain.

At the northwest corner of Amsterdam Avenue and West 75th Street is this 1889 building originally a stables and then The New York Cab Company, and latterly a parking garage. Blocks between 75th and 77th and Amsterdam and Broadway became a livery district known as Stable Row around 1900; this is one of the few that remain.

The New York Cab Company (318 – 330 Amsterdam at 75th St) is a Romanesque Revival style building designed by C. Abbott French and built between 1888-1890. It originally was one of the numerous stables run by a a firm incorporated in 1884 that provided horse-drawn carriage service using practices later adopted by the auto taxi industry, including fixed fares, badged drivers and yellow-painted carriages. With the coming of both the automobile and the subway in the first decade of the 20th century, the stable was converted to a succession of automotive tenants in 1910. A painted sign for Sheridan Square Motors still existed on the western wall of the building as of 2009. The building was landmarked by the city in 2006 with the finding that the building, “…has a special character, special historical and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage, and cultural characteristics of New York City.” Michael Min

Pink Lady: The Hotel Lucerne, 201 West 79th at Amsterdam, was built in 1904, encased in a riot of molding, had been recast as luxury apartments but has returned to its old role as a boutique hotel.

At Amsterdam and West 80th, another example of the casual excellence arhictects could bring, a couple of decades either side of 1900, to multifamily buildings, and art that has ben willfully lost. Right: Saint Agnes Library, 444 Amsterdam north of West 81st:

Beginning in 1893 as a parish library at St. Agnes Chapel on West 91st Street, the St. Agnes Branch also housed a small collection for the Library for the Blind. The following year, in 1894, the chapel’s pastor, in order to keep pace with a rapidly growing community, expanded the library to neighborhood status. St. Agnes Free Library was chartered by the University of the State of New York and moved several times before its consolidation with The New York Public Library in 1901. In 1906, the St. Agnes Branch opened its doors in its present home on Amsterdam Avenue. NYPL

At Amsterdam and West 82nd, I found a very old awning sign for “something & insurance”; when the Google Photo Truck passed by previously, there was a classic red, white and blue plastic letter sign for a La Gran Esquina Barber Shop there.

471-475 Amsterdam is awesome. It is an eleven story, brick and terra-cotta, Utilitarian style warehouse with neo-Renaissance elements designed by George S. Kingsley and built in 1922-1923 between West 82nd and West 83rd.

The original owners were the Metropolitan Fireproof Storage Warehouse Corp. Their M is found among the decorative detail on the front facade. Sofia [Brothers] purchased the property in 1950: “Sofia Brothers interests have added another warehouse to their holdings through the purchase of the eleven-story building at 471-475 Amsterdam Avenue, occupied by the Metropolitan Fireproof Warehouse… The building, constructed in 1925, fronts seventy-four feet on Amsterdam Avenue and Eighty-third Streets. In addition to warehouse space, the building contains exhibition and sales rooms and other facilities. Sofia Brothers, established forty years ago, have three other warehouses in the city.” (New York Times, 5 Dec. 1950).

[T]he origins of Sofia Bros. were in the Bronx. In 1900 Theodore Sofia and his wife, Theresa Sofia, lived at 1221 Intervale Ave., the Bronx. They were immigrants from Italy (Theodore in 1879 and Theresa in 1883), and they had eight children ranging in age from 15 years to 4 months, all born in New York. Theodore worked as a street sweeper for the New York City Dept. of Public Works. By 1910 Theodore Sofia had died, and his widow, Theresa Sofia, still lived at 1221 Intervale Ave. The family maintained a boarding and livery stable at this address. This stable was the origin of the Sofia Bros. moving and storage business. The brothers in the business were Charles Anthony Sofia (1885-1962), Frank Sofia (1886-1937), Patrick Sofia (1890-1966), James John Sofia (1892-?), Theodore Charles Sofia (1895-1955), and John Sofia (1899-1985). Mater Familias was Theresa Sofia (1857-1941). In the 1910 U. S. Census all of the boys were working in the stable except John, who was only 10 years old. Much more at Walter Grutchfield’s page

Reminders of its 1920s vintage remain on the building, from the clock and “safety and security” lettering to the classic “hardware” sign under the de rigueur vinyl awning sign on Klosty Hardware.

If I were writing this page just a few years ago, a highlight at Amsterdam and West 73rd would have been the multicolored neon sign at the P&G Cafe. The P&G lost its lease in 2008 and was forced to move (to 380 Columbus at West 78th) and most of the sign couldn’t be preserved because fragile electronic and metal parts were severely rusted from being out in the open for over 50 years. The sign had been designed by P&G owner Steve Chahalis’ grandfather after his return from WWII service.

In August 2011 the P&G announced it was closing in its second location.

At West 83rd and Amsterdam, though, the Hi-Life Bar and Grill survives; like the old P&G it was likely once a shot and a beer joint, but it has adapted to the realities of life on the Upper west side, and added brunch. There’s also a branch on 2nd Avenue and East 78th, also with a neon sign.

Hi-Life’s website states it has been in business since 1991. Question: did it take over a locale with the old sign, or was the sign designed specifically for the venue?

I passed Good Enough to Eat at 483 Amsterdam between West 83rd and West 84th, and was struck by the line, which went all the way down the block. The restaurant has been an Amsterdam Avenue fixture since 1981. As is usual, up and down reviews. Right: The DOME Project, an acronym for Developing Opportunities Through Meaningful Education, is a neighborhood organization formed in 1973 to help area youths who are “economically, socially, and academically challenged to focus on their education as a means to success.”

West-Park Presbyterian Church at the NW corner of Amsterdam Avenue and West 86th Street was built in sections from 1884-1890 as a brownstone romanesque revival by architect Leopold Eidlitz. The congregation was founded in 1853, as a cornerstone indicates; the hyphen in the name is because it was founded as Park Presbyterian and merged with West Presbyterian in 1911. The building was designated by the NYC Landmarks Commission in January 2010 — against the wishes of the congregation, who wanted to convert part of the building into apartments to raise money for the church’s interior restoration.

Schatzie The Butcher, Alan Tony Schatz’ butcher shop has been in business since 1911 and recently [spring of 2010] moved here to Amsterdam and West 87th from its former location east of Central Park on Madison Avenue and 88th. Schatzie is a character… Check the videos here. Barney Greengrass, The Sturgeon King, is on the same block.

Right: Shankman One Hour Cleaners, whose sign is now showing signs of age.

Central Baptist Church, SE corner of Amsterdam and West 92nd Street, constructed 1915-1916. The AIA Guide advises marveling at the crockets (ornamental carvings of buds and flowers) on the finials (the tapered extensions at the top of the tower).

Right: Moderne entrance at 175 West 92nd, on a building that otherwise doesn’t look Moderne.

Awhile ago West 94th between Amsterdam and Columbus got patches of brick paving and traffic control curb treatments, but I’m not sure quite why.

The granite ashlar Holy Name of Jesus Roman Catholic Church (1898; steeple, 1918) and its K-8 grade school (1904) dominate Amsterdam Avenue’s west side between West 96th and 97th Streets. The church was organized in 1868 on the Bloomingdale Road (now Broadway) at what is now West 97th.

Across from the church on the NW corner of Amsterdam and West 96th stands the most monumental CVS drugstore in the city, with some of the biggest Ionic columns you’ll see. The former East River Savings Bank was constructed in 1926-1927 as a classic temple worshiping the power of savings; inscriptions exhorting the public to save money are inscribed on the pediment. As the medallion indicates the bank was founded in 1848 and by a series of mergers became part of Marine Midland Bank, whose assets are now controlled by HSBC.

It’s not in the architectural guidebooks, but 143 West 96th, Kipling Arms, near Amsterdam, is replete with detail around its arched front entrance like various snakes, wyverns, dragons and such. They liked to do that in the era this building was constructed. Not sure if the building was named for the immortal Rudyard, whose poem “If” is among my favorites:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or, being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or, being hated, don’t give way to hating,

And yet don’t look too good, nor talk too wise …

… If you can talk with crowds and keep your virtue,

Or walk with kings – nor lose the common touch;

If neither foes nor loving friends can hurt you;

If all men count with you, but none too much;

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run –

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And – which is more – you’ll be a Man my son!

There’s a handsome brownstone building filling much of the west side of the Amsterdam Avenue block between West 97th and West 98th that has a pet goods store called Little Creatures in one of the street level shop spaces. Most likely the store is named for the 1985 Talking Heads album, but there are in fact a couple of little creatures on the peaked parts of the roofline. Or maybe just a couple of Dutchmen.

We’ve seen Holy Name of Jesus Church previously, but I’ll show it to you again in context with the new condo behemoth at 2628 Broadway between West 99th and 100th, the Ariel East. The blue glass giant has tended to horn in on the sky formerly dominated by the church steeples of HNJ and of St. Michael’s Episcopal Church on the corner of Amsterdam and West 99th. Ariel West, across Broadway, isn’t quite as tall. The towers were built before rezoning prohibited this kind of height from appearing further in the neighborhood.

St. Michael’s, meanwhile, has soldiered on since 1891, a year in which probably no one thought buildings would get much taller than this. The arched openings at the top vouchsafe you a view of the church bells.

Curious about the big blue behemoth, I slouched down 99th to Broadway, where I found the old Embassy Metro as well as a Bloomingdale Road survivor, the Henry Grimm Building, constructed in 1871, when the wagon trail connected several small towns called Harsenville and the still-surviving Manhattanville. The Metro Diner holds down the ground floor.

The theatre has been closed for several years, as its exterior is more or less the same, but the interior has been gutted. Rumors have had it becoming a Gristede’s or an Urban Outfitters, but it awaited a buyer in the summer of 2010.

Returning to Amsterdam Avenue via West 101st, I noticed a mammoth brick building, whose size reminded me of the Sofia Brothers Storage building (above). The winged wheel motif, though, indicates this has always been a parking garage with perhaps auto repair on the ground floor. Lots more detail on this particular garage than you’ll find on any of the heinously ugly parking garages being built today (I haven’t seen a parking garage built after 1950 that wasn’t heinously ugly.)

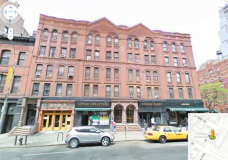

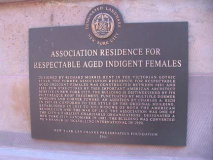

The richly dormered and peaked Residence for Respectable Aged Indigent Females, Amsterdam between W.103rd and 104th, was designed by Richard Morris Hunt and completed in 1883, making it one of the oldest buildings on this stretch of Amsterdam Avenue. The original occupant was organized in 1813 to aid widows of the Revolution and War of 1812, making it one of the USA’s first established charitable concerns. The building came under control of American Youth Hostels, providing affordable lodgings to travelers, in 1990. The building was designated by the NYC Landmarks Commission in 1983.

Richard Morris Hunt was the first American to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and, after his return to New York, he became the most prominent architect in the city. Early in his career, Hunt designed a series of avant-garde buildings, introducing French architectural ideas to America. These include the Stuyvesant (1870-73; demolished), the earliest apartment house planned for the middle class, the Roosevelt Building (1873-74), a cast-iron building with a clearly expressed structure, and the Tribune Building (1873-76; demolished), an early skyscraper that was the third office building in the city that incorporated an elevator. In 1882, Hunt designed William K. Vanderbilt’s mansion on Fifth Avenue at Fifty-second Street, an early example of a mansion designed in direct reference to European historical precedents. He later designed many city mansions and country estates for the Vanderbilts and other wealthy New Yorkers. While many of his homes in Newport and similar summer colonies are extant, few of his city buildings still stand. NYC Architecture

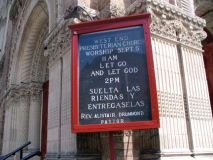

Yet another phantasmagoric church on an avenue full of them is the West End Presbyterian Church at W. 105th, with its gradually tapering campanile. Rapunzel, if you’re up there, let down your hair. The church was designed by Henry F. Kilburn and completed in 1891.

One more example of everyday apartment house excellence of the Upper West Side before I kicked it in the head for the day. Much more from upper Manhattan to come.