BY SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY contributor

Situated on the edge of the glacial terminal moraine, Kew Gardens offers historic architecture, winding streets, and a village environment. The neighborhood is completely planned out, but has an organic centuries-old feel. A sense of place, a relationship with nature, one that gives residents pride and makes a trip to the grocery feel like a leisurely stroll.

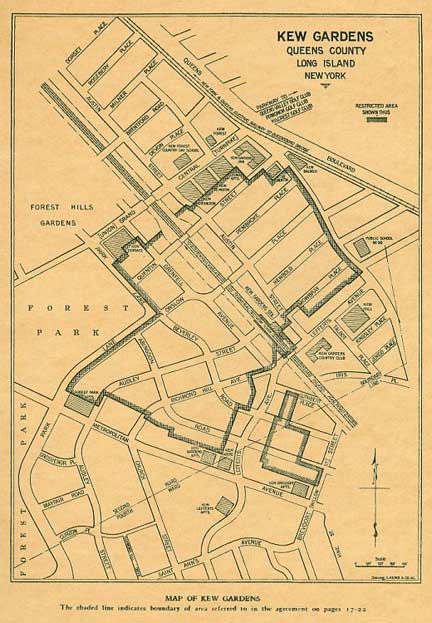

Designed by Richmond Hill builder Albon Platt Man and developed by his son Alrick Hubbell Man, the neighborhood is a combination of winding park-like streets and an alphabetic street grid. On the left is a prewar map of the area.

Like the neighboring Forest Hills Gardens,the early homes of Kew Gardens had strict covenants to prevent overdevelopment. The restricted area on the map to the left was limited to single-family homes, with larger apartment buildings relegated to the neighborhood’s periphery.

By the 1930s, the Kew Gardens Corporation was bankrupt, the early film stars who owned property in Kew Gardens had moved west, and the Kew Gardens Country Club was razed in favor of a movie theater.

In 1937, the streetcar line along Queens Boulevard was supplemented by a subway line, with an express station at Union Turnpike.

At this time, the city was also imposing the numbered grid upon Queens, forcing neighborhoods to ditch their street names in favor of numbers. The Kew Gardens grid once had Ibis, Juno, Kingsley, Lefferts, Mowbray, Newbold, Onslow, Pembroke, and Quentin.

Today, only Lefferts, Mowbray, and Onslow remain as witnesses to the pre-grid period. Mowbray even has house numbers that are unrelated to the overall borough grid. map courtesy Kew Gardens History

For more on Kew Gardens’ and Richomd Hill’s development and history, see Carl Ballenas’ and Nancy Cataldi’s Arcadia Books publication Images of America: Richmond Hill and NYC historian Barry Lewis’ Kew Gardens: Urban Village in the Big City.

The Austin Street Underpass

The Austin Street Underpass snakes below Union Turnpike and Jackie Robinson Parkway. It once had parkway-style wooden lampposts. The street scene has changed little in the past 80 years.

The pedestrian entrance to this tunnel resembles a subway station entrance, minus the bathroom tiles. Its passage resembles a platform.

The Kew Gardens station on the Long Island Railroad has been operating since 1910, with the same station house on the city-bound platform.

Prior to the railroad’s relocation the tracks ran slightly to the north. In 1875, the Hopedale station opened for the new Maple Grove cemetery; it closed in 1884. To the south of the old station [at about today’s 83rd Avenue and Grenfell Street] there was a glacial kettle pond called Crystal Lake.

This 1909 Bromley map shows the holdings of Albon P. Man in what would become Kew Gardens. Metropolitan Avenue (left), Lefferts Boulevard (bottom) Union Turnpike (top) and Newtown Road, now Kew Gardens Road, and Hoffman Boulevard, now Queens Boulevard, are recognizable on the map.

Above the Tracks

Crystal Lake, which was drained and filled by 1909;

Beers Atlas 1873 view of Kew Gardens/Richmond Hill, which shows Man’s vision for the development. Most of the roads were not constructed and the present map looks quite different. map courtesy Kew Gardens History

From the ForgottenBook: The Kew Gardens station house is a handsome, venerable ridge-roofed building, but of even greater interest is the span that takes Lefferts over the tracks: it’s lined on both sides with commercial buildings. A complicated engineering solution encompasses three separate bridges on Lefferts: one for the roadway, and two on each side that support the buildings. According toKew Gardens: Urban Village in the Big City author and PBS-TV host Barry Lewis, the store’s bridges actually run through the buildings’ roofs, with the storefronts hung from the bridges like a curtain on a rod. The engineering principle is similar to that of the circa-1565 Ponte Vecchio (Old Bridge) in Florence, Italy.

On the left is Kew Gardens Cinemas, an indie film theater built in 1935. As the neighborhood declined, it slid into a seedy stage, showing porn flicks. In 1999, it reopened as an art house theater. Behind the theater, the massive Shellball Apartments rise above the neighborhood. It’s one of several 1920s developments along the neighborhood’s edge.

Chimneys keep the stores warm on the bridge. Just across the street, the storefront without the awning is the Q Gardens Gallery, where you can find Ron Marzlock, local historian and Queens Chronicle contributor. Marzlock welcomes old photos of Queens, and I always stop by to visit him whenever I’m in Kew Gardens. Underneath the satellite dish is the Austin Ale House, a popular local tavern.

On Austin Street

Austin Street runs along the tracks from Eliot Avenue to Metropolitan Avenue, as a less crowded parallel to Queens Boulevard. The former tennis courts of the country club are presently a rundown sitting area with a film-themed mural. The apartments above the nearby Austin Ale House once housed a young Rodney Dangerfield and waitress Kitty Genovese, who was murdered under shameful circumstances nearby in 1964. The towering Romanesque revival building is The Mowbray, a 1920s development.

The gate behind the Mowbray Apartments was once the Oriole Tea Room, a restaurant. The 1924 apartment building also has ecclesiastical-style decorations on its balconies. The growth of apartments led to the creation of the Kew Gardens Civic Association in 1914. It has been fighting overdevelopment ever since.

Kew Hall Apartments have a circular private driveway and garden inside. Built in 1922, it was based on Manhattan’s Dakota Apartments. The longtime co-op recently turned condo and renamedTalbot Gardens, restoring its full-time concierge and gate. Situated at the corner of Lefferts Boulevard and Talbot Street, the building takes up half a block.

Where Lefferts Begins

A hilltop marks the start of Lefferts Boulevard at Kew Gardens Road. From here, it runs 5 miles down towards JFK Airport. Its southern end was once East Hamilton Beach, a fishing enclave that was razed for the airports expansion in the 1950s. West Hamilton Beach (formerly Ramblersville) is still around.

PS 99, the alma mater of Jerry Springer, faces the local Reformed Church, presently housing a Korean congregation.

Opened in 1875, Maple Grove Cemetery keeper’s house dates to 1880. The cemetery [Kew Gardens road south of 83rd Avenue) dates to a time when “burial parks” were beautiful, with ponds, winding streets, and grove of trees: not like today’s crowded graveyards.

The cemetery led to the creation of a train station, which led to the creation of the neighborhood. Kew Gardens Road is a colonial period route whose traffic had been siphoned off by nearby Queens Boulevard in the late 19th century.

The Classic condos opened in 2008 [Kew Gardens Road and 83rd Drive], an apartment palace fashioned out of the former Chatillon Scale factory, a rare manufacturer in the neighborhood. The factory closed in 2005.

While some local preservationists hoped to see the factory’s Tudor style incorporated into the condo, it has a decidedly Mediterranean palace look. The top is plaster, the bottom is brick.

But that’s still better than the numerous brick boxes around Queens that pass off as “luxury condos” these days.

A private park runs through the Georgian-style Dale Gardens campus (125th and 126th Streets, between Austin Street and Maple Grove Cemetery).

Enjoy the view before it’s gone. As the city continues to phase out local water tanks, the end of Austin Street, at 126th, will no longer be so easily defined.

Water tanks are a common sight in small-town America, but a rarity in this city. Most of the city’s remaining tanks are located in Queens, and Kew Gardens has two of them.

There was once a time when every LIRR station had a hotel alongside it. For Kew Gardens, the Homestead Hotel [83 Grenfell Street between Audley Street and 83rd Avenue] served that purpose. The manor-style building opened in 1921. It hosted weddings, too. Today, it is a seniors residence. On the next city-bound station, the Forest Hills Inn is presently an apartment building. Both hotels once attracted crowds of tennis spectators, when the US Open played in Forest Hills. photo left courtesy Kew Gardens History

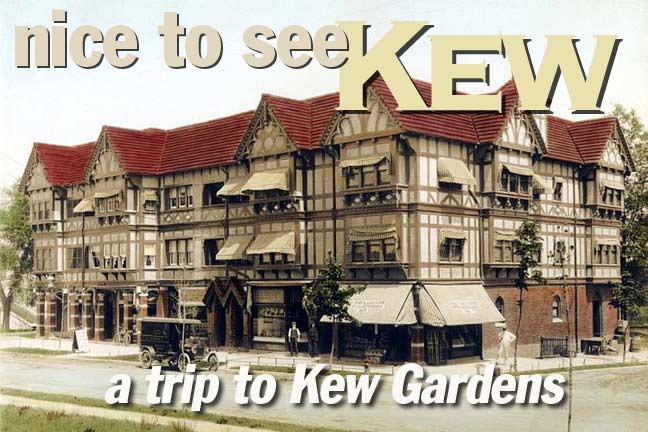

Every village has a center, and for Kew Gardens, it’s the Tudor-style Homestead building [Lefferts Blvd. and 83rd Avenue]. It was built in 1914, but has a centuries-old appearance. Over the years, this building has been reduced in size, but he baker on its corner keeps its name in mind. In 2006, an out-of-context brick box was built behind the Homestead, sandwiched between two Tudors. This is why landmarking is needed here. photo left courtesy Kew Gardens History

The borough’s sole Anglo-Japanese building [84-62 Beverly Road] is in near ruin, with first-floor windows cemented and rain gutters hanging over. On the front door, a hostile handmade sign tells the curious to stay away. A cell phone number is given for “any questions.” I can certainly think of a few polite questions, related to why such monumental neglect is not a crime.

One of a kind homes can be found around the neighborhood, including one bisected by a driveway and one [at 80-55 Park Lane] that coincidentally resembles the Lubavitch headquarters in Brooklyn. In contrast to the home above, these two are lovingly maintained by their respective owners. The house on the bottom was once owned by film star Charlie Chaplin.

Another historic-style corner marks Lefferts Boulevard at Metropolitan Avenue.

Up the block, All Green Towers apartment building has a medieval-style entrance gate.

The avenue once had streetcars along its length, which the Q54 bus route follows today. The nearly straight avenue, built as the Williamsburg(h) and Jamaica Turnpike in the early 1800s, stretches 8.2 miles from Brooklyn’s Williamsburg to Jamaica, where it merges in a triangle with Kew Gardens Road and Jamaica Avenue.

Grosvenor Road [properly pronounced Gruh-ve-ner] shows the dangers of unrestricted development as ugly brick condo boxes elbow their way into a village of Tudor houses. It’s like Banksy defacing a Thomas Kinkade landscape! Sadly, residents hoping to cash in on their homes largely oppose landmarking, arguing that it impedes their freedom to alter their homes. A brick multi-family box is certainly more than an alteration!

[We need landmarking to save houses from their owners — your webmaster]

Don’t assume that I oppose apartment buildings. Windsor Court on the left is an excellent example of a building that fits into the village. But modern developers don’t have any sense of design. At 116th Street and Curzon Road, a lone Tudor house is dwarfed by 21st century condos. Notice how narrow the road is, unable to handle the masses living in the new towers. I presume the namesake is British diplomat Lord Curzon, who demarcated the Russian-Polish border in 1919. It is known as the Curzon Line.

Before Kew Gardens, Albon Platt Man founded Richmond Hill in 1869, a suburb of Victorian homes named after Richmond-on-Thames, a suburb of London. Likewise, neighboring Kew Gardens is named after Kew, ahistoric London botanical garden.

Large porches, round windows, and sizable yards define the oldest homes in both neighborhoods. This winter scene appears as bucolic as 1869, but behind the camera are apartment buildings of a different style.

In Kew Gardens, the English theme is also echoed with the Hampton Court apartments, tucked inside Forest Park. They are named after a palace where Henry VIII once lived.

The highest point in Kew Gardens (outside the cemetery) is on Audley Street, where a water tower has stood in one form or another since the early years of Richmond Hill. It was once surrounded by a golf course, and the clubhouse stood next to the water tower until 2005, when it was replaced by this brick mansion. From the top of the tower, it is possible to see much of Queens, but I chose not to trespass.

With the right height and appearance, a modern building can fit into the village, as demonstrated by Anshe Shalom. Translated as “people of peace,” it was built in 1970 for a Conservative Jewish congregation. Responding to local demographic changes, it became Orthodox in 2008, renamed Anshe Shalom Chabad.

Often with synagogues, Reform and Conservative build big, but the children tend to move away or assimilate. In contrast, the Orthodox generally, avoid building large temples, preferring to use their funds for yeshivas (religious schools). The Orthodox are more attached to their shuls and schools, and are often the last to leave a neighborhood.

The landscape of Forest Park has the same verdant setting as Central Park, but it has only a few sculptures in it. Among them is the prophet Job [pronounced joeb] by Polish-born Nathan Rapoport. The statue is a memorial to the holocaust, once owned by local residents Dr. Murray and Sylvia Fuhrman. One of the Job statues was donated to the Yad Vashem memorial in Jerusalem, and the other to Forest Park [at Forest Park Drive and Park Lane].

Job was given a harsh test of his faith, as were those who experienced the holocaust. In the cold snow, I could only imagine the hardship my great-grandparents experienced. Rapoport fled east from the Nazis, surviving the war in Soviet Russia. He later immigrated to New York. His memorial sculptures can also be found in Liberty State Park, Warsaw, and kibbutz Yad Mordechai.

At the northern tip of Forest Park [Park Lane and Union Turnpike] is the Overlook, a knob-like hill that provides views of Forest Hills Gardens. The park’s administration building dates to 1911.The City of Brooklyn purchased land for the park in 1895 and had noted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted survey the park. His signature is the winding Forest Park Drive. The park has a bandshell, greenhouse, carousel, and golf course, among other attractions.

The Crossroads Building of the 1980s [Queens Boulevard and Union Turnpike] was an ugly addition to the skyline, replacing the Kew Gardens General Hospital, which itself was a former hotel.

It also encountered local opposition, but its 300,000 square feet of space, including a garage, community room and numerous law offices. Its location is ideal, with 4 bus lines, an express subway station, and three major highways nearby. I have no idea what the architect was thinking by giving the building wings on its roofline.

In a grotesque parody of the Lefferts Boulevard bridge, the Union Turnpike overpass also has buildings along its shoulders- the massive Park Lane Towers co-op, built in 1975 by developer Samuel Lefrak, who later affected the spelling LeFrak. At a height of 20 floors, many local homeowners opposed their creation, hiring attorney Mario Cuomo to represent them. Unlike his Willets Pointlawsuit, Cuomo lost this one. He later went on to become a 3-term governor.

Newcombe Square is a little semicircle at the split of Queens Boulevard and Kew Gardens Road. Richard S. Newcombe served as the Queens District Attorney between 1925 and 1929.

According to the plaque, he was a “distinguished citizen and public advocate who gave himself unselfishly to the advancement of good government and the advancement of youth.”

In the background are the Kew Bolmer apartments, which mark the first stop on the Q10 bus line. You can take it to JFK Airport. The neighborhood’s midway location between JFK and LaGuardia makes it popular with airline workers.

The mezzanine of the Union Turnpike station mezzanine is bisected by Union Turnpike, and it once had a platform for buses inside the subway station. Those buses caused traffic backups and this unique bus stop was discontinued. Glass bricks separate the platform from the busy highway.

No talk about local subways is complete without mentioning the retired Redbird car stationed outside Borough Hall, literally above the working subway line. [The R-32/R33 IRT ‘Redbirds’ never worked the IND Queens Boulevard line, though.]

This completes our visit to scenic Kew Gardens, the village in the heart of Queens. These photo was taken during the extraordinarily snowy period of Jan. 2011.

All text and most photos by Sergey Kadinsky

All text and most photos by Sergey Kadinsky

Sergey Kadinsky has been living in Queens since age eight. His interest in journalism can be traced back to childhood, when he made a hobby out of writing letters to the editors of local newspapers. He is a writer who aspires to a career in journalism and politics. At times, he has been spotted giving tourist-friendly monologues atop Gray Line buses. He also paints murals that contain maze puzzles. His website is mazeartist.

1/30/11

1 comment

[…] stucco; the roof features curves reminiscent of Japanese architecture — just gorgeous. This Forgotten New York article calls the building in its present state a “near ruin,” with hostile handmade […]

Comments are closed.