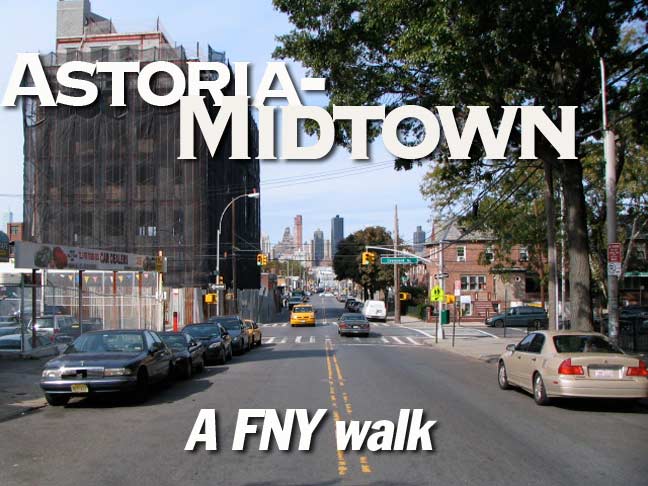

Hello ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, welcome to Forgotten New York Walks, a new FNY category and the first since FNY Slices was instituted in July 2007. Walks will feature what the title indicates, a walk from one neighborhood to the other — especially when the two neighborhoods are completely disparate. In 2007 I did a page about a walk from Penn Station to Long Island City via the Wards Island and Triboro (RFK) Bridges, and placed it in Street Scenes. The glut of pages in Street Scenes has been a bit of a problem with FNY for some time — I think it has 3 times the pages of its closest competitor — so I think a new category like FNY Walks is a good way to ease the problem, in part.

FNY Walks also marks the debut of a new FNY category plate. I create these in Photoshop using the FNY logo (employing the Fragile font and in use from Day 1 in 1998) and Frankie, a weathered-look knockoff of Franklin Gothic, also used as a FNY font. I don’t like to use too many fonts, though an old fashioned font called Attic Antique is used on my ForgottenTours pages.

I hope to make FNY Walks a bit breezier and not so logorrheic, though my tendency is to ramble on to cram as much information in as I can. Let’s see how the first page goes.

WAYFARING: Astoria to Grand Central Terminal

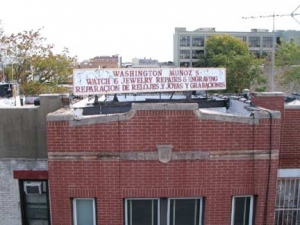

I took the BMT Astoria (N train) to 36th Avenue and alit on the platform. I was attracted immediately to the roof sign on one of the buildings on 31st Street, which the el runs over. The serif letters may be stenciled onto the surface.

Many of Queens’ subway and el stations carry the former names of the street. These were originally placed on signs when the line was built, or the names changed, so people who were more used to the names than the numbers would know where the station was. Queens began changing its named, and occasionally numbered, streets to a uniform number system in the 1910s and grandfathered it in throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s. The names are now kept for tradition’s sake more than anything else.

This 1909 map predates by about a decade the construction of the el on Debevoise Avenue, now 31st Street. 36th Avenue was once Washington Avenue. Also note the diagonal Old Ridge Road, with the trolley line (see below)

Much like Greenpoint Avenue in Brooklyn, a couple of miles southwest, residences are side by side with live poultry slaughter abattoirs on 31st Street.

An internet search indicates American Elevator was established in 1983 but its plastic letter sign seems older than that. This style is a particular favorite of mine.

I have never gotten a call from a woman saying she’s naked in midtown, but there is yet time. I thought this was a phone sex ad but it’s actually an online serial from Elle Magazine.

Turning west on 37th Avenue, there’s a substantial 9/11/01 themed mural on the SW corner of 30th Street. A remnant of an aboriginal Astoria route called Old Ridge Road can be seen running south from 37th Avenue between 29th and 30th, and serendipitously the green Citigroup tower is smack in the middle of the shot. A careful inspection of the Old Ridge Road pavement shows an odd rail or two from the days when a trolley line used it; see above map.

37th Avenue and Crescent Street, which kept its name due to its slightly bowed path through Long Island City and Astoria. A leftover Shepard Fairey Obama campaign poster can be seen in the window of this very narrow brick building that is over a century old.

Pressing further into the enclave known as Ravenswood, you notice a preponderance of auto body repair shops, fender hammerers, and flat fixers. The area is primarily industrial, though it had formerly been the home of magnificent mansions overlooking the East River to Manhattan. Since 1951 the Ravenswood Houses have been the primary residential region here.

Sometimes former NYC Parks Commissioner Henry Stern simply stated the obvious in naming pocket parks, like the one formed by 37th Avenue, 14th and 21st Streets (Ravenswood’s layout skips a few numbers). These are almost the only trees in the immediate area.

Thought this was a great shot, WunderBar on 11th Street just south of 37th Avenue, Big Allis smokestacks in the rear. Officially Ravenswood #3, it is a gigantic power generator on Vernon Boulevard between 37th and 40th Avenues, constructed by the Allis-Chalmers Corp. in 1965. It presently produced about 20% of NYC’s total electric power. It was constructed for Con Edison, but was purchased by Keyspan/National Grid and was in turn sold to TransCanada Corp. in 2008. Con Ed still has a steam generator on the site. Big Allis’ stacks are a defining landmark on the west end of Long Island.

WunderBar opened in early 2009 and is hardly the wurst bierkeller in the neighborhood.

Turning northeast on 11th Street, I spotted what at first seemed to be a horribly disfiguring building front, but it has these tiny terra cotta ornaments above the windows that assuage the effect a little. I thought these 2 bow-front brick houses were identical bookends but one has 3 stories, the other two.

At 36-40 I stumbled on none other than the world headquarters of Troma Films, the world’s #1 shoxploitation movie studios, founded in 1974 by Lloyd Kaufman and Michael Herz. The Toxic Avenger, which came out in 1985, is probably Troma’s biggest moneymaker, inspiring 3 sequels and an animated version.

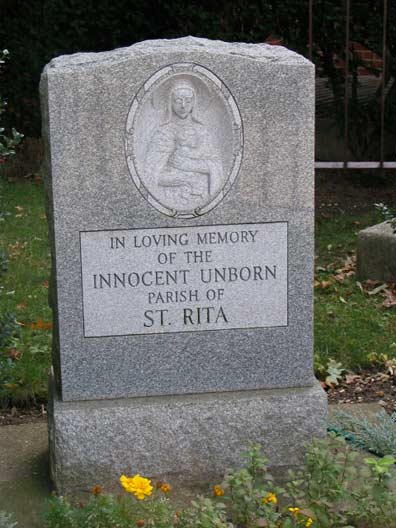

At the corner of 11th Street and 36th Avenue is the parish of St. Rita church. Pastor Jose Carlos da Silva is from Brazil and there are some Portuguese-language Masses on the schedule, indicating a Brazilian populaton in the region. The church was organized in 1900, making 2010 their 110th anniversary.

The handsome brick apartment building at the NW corner of 11th Street and 36th Avenue is marred by a huge pipe coming down the front from the roof. What is the purpose of these pipes, seen on many buildings?

The pipe takes care of exhaust fumes produced by the deli.

Corner grocery, 9th Street and 36th Avenue

At 36th Avenue and Vernon Boulevard is the entrance of the Roosevelt Island Bridge, the only means of vehicular entry onto the island. Until its opening in 1955 the only means of getting to the island were by boat; a trolley line also stopped on the Queensboro Bridge and an elevator allowed passengers to enter the island which, until the mid-1970s, was home only to hospitals.

Taking a last look while still in Queens (Roosevelt Island is politically in Manhattan) I embarked on the new pedestrian crossing. The curved ‘cage’ type railing is designed to save pedestrians from falling into the East River, but also somewhat impedes miscreants from throwing objects over the fence into the river. The new sidewalks are in fact somewhat soft, with a little ‘give’ to them, and were probably designed that way in a concession to runners.

Maroon is the favored color in bridge spans when being repainted for the last couple of decades, even though years in the bright sun tend to fade it to pink. The crossing gates come down whenever the bridge is raised. The 59th Street/Quensboro Bridge is in view from the south side of the Roosevelt Island Bridge.

The new cage-type fence is not photography friendly, and authorities such as the NYPD and the federal government frown on bridge photography as a whole, but a glimpse of thin-layer side of the East River, and the RFK/Triboro Bridge, is possible via a narrow space between fence divisions. Right: new bucket-style walkway lamp, mounted on bridge girder.

Since the reconstruction, the best view can be had by looking across the roadway to the south side of the bridge. Finally, the Roosevelt Island apartment towers come into view. Most were built from 1973-1976 according to a plan devised by the Urban Development Corporation, and prominent architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee were hired to build the island’s new residential town, as well as Main Street and twin promenades on either side of the island.

There must have been a true Wild West feel to the place in the 1970s. Ruins of the old penitential past of the island, as its use as a quarantine area, still abounded; the ruined Smallpox Hospital is still there on the southern tip. A small section of the old 1839 Blackwells Island Asylum, called the Octagon for its 8-sided tower, stood like the statue of Ozymandias. It is now the centerpiece of a magnificent upscale apartment complex.

A look back at Ravenswood from the parking garage ramp. Cars were prohibited from Roosevelt Island’s roads when the complex was built in the 1970s, with cars restricted to the Motorgate parking lot. That regulation has been eased (in fact original residents could not have dogs).

There’s always been a flock of supermarkets that have restricted themselves to Manhattan, and as such have always been somewhat mysterious to me, such as Gristede’s, Sloan’s, D’Agostinos, and Food Emporium, though I’ve spotted a D’Ag in Brooklyn Heights (I almost consider Brooklyn Heights and now Williamsburg as Manhattan outposts in Brooklyn).

looking north on Main Street, Roosevelt Island. I did not have time to walk to the north end, featuring Coler Goldwater Hospital, the Octagon, and the Roosevelt Island Lighthouse, so I headed south along Main Street, which remains thinly stocked with retail establishments. One of Roosevelt Island’s features is enclosed sidewalks with seating on Main Street’s east side, so that residents don’t have to get wet when traversing the strip.T he island’s public school is PS/IS 217.

The Chapel of the Good Shepherd/St. Frances Cabrini Roman Catholic Church was designed by British architect Frederick Clarke Withers and opened in 1889, as a place for worship for workers at prisons, ‘insane asylums’ and quarantine hospitals that then dominated Blackwell’s Island.

Johnson/Burgee Apartments, Main Street, across from the chapel.

On previous visits to the island I had found the 1796 James Blackwell Farmhouse more or less in ruins. After NYC’s purchase of the island from the Blackwell family in 1828 the house was used for administrative offices. It is the only clapboard house on the island even though it has been resided during a recent restoration.

Main Street from the farmhouse, looking north (left) and south toward the Queensboro Bridge.

A look at the West Channel of the East River, showing New York Presbyterian Medical Center (white building, left) and the Queensboro Bridge, right.

The East Channel view is rather more mundane: the smokestacks of Big Allis. Right: a new park near the new Riverwalk Court high rise is something of a trompe d’oeil: the towers in the rear are in Manhattan, not Roosevelt Island.

Roosevelt is an island of many icons, some left to rot for decades and only re-appreciated later, while others have been awe inspiring since the day they opened. Manhattanites consider this the “59th Street Bridge” while Queens-ites call it the Queensboro. It has passed over the island since its superstructure began to take shape in 1903. The Roosevelt Island tram opened in 1976, the same year the island’s residential buildings did. After a 2006 incident in which two trams were suspended over the river for 90 minutes, officials knew that renovations and upgrades were necessary and thus, the line was shuttered March 1, 2010, and hopes to reopen in November. Extensive action-movie sequences involving the tram were used in 1981’s Nighthawks starring Sylvester Stallone and 2002’s Spider-Man.

At one time, five trolley shelters like this one were at the trolley stop on the Manhattan end of the Queensboro. Over the years, three of them have been dismantled and disappeared. In 1977, one was shipped to the Brooklyn Children’s Museum in Bedford-Stuyvesant, where it served as the entrance portal, and it continued in that role until 2005, when it was loaded onto a flatbed truck and transported here to Roosevelt Island, where in spring and summer it serves as the island’s Visitor Center. The remaining kiosk is still at the Queensboro Bridge entrance, where it continues to deteriorate.

The kiosks were designed by the Queensboro’s architects, Henry Hornbostel and Gustav Lindenthal. Inside you will find interlocking herringbone Guastavino tiles, also seen under 1st Avenue on the Manhattan side.

1910-era flourishes abound: elegant roofline ”Entrance” and “Exit” signs; a terra-cotta bay with an angular shield topped by a leafy garland, a pilaster decorated with a Greek key motif, and brackets wrapped in ornamental scrollwork.

Riverwalk Court is one of a number of new residential high rises on the south end of the island. It replaced now-razed nurses’ housing for nearby Goldwater Memorial Hospital, which since merged with Bird S. Coler Memorial on the north end of the island. Right: compare the form-is-function Roosevelt Island subway entrance to the 1910 trolly kiosk, and compare the attitudes toward public works in 1910 and 1989, when the subway station opened.

Since the tram was shut down I instead took the train, which is very deep here — about 3 escalators down deep. There is a deeper level still, carrying Long Island Rail Road tracks that will be used when/if the East Side LIRR connection with Grand Central Terminal is completed. Ongoing official estimates say 2016, so you can add about a decade to that and make it 2026.

[Station renovations encompassing that tunnel construction have stripped the orange tiles from the Lexington Avenue station. Since it’s not the 70s anymore and glazed orange has gone out of style, it’s likely a blander color will replace them.]

Alighting at Lexington and East 62nd, I decided to head downtown to Granc Central Terminal. Left: don’t know much about this building but the ornamental ironwork is spectacular.

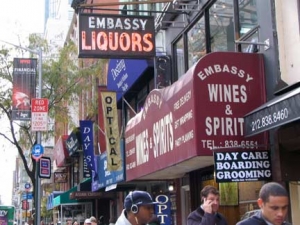

Embassy Liquors, with its red and white neon sign, between east 61st and 62nd. On the second floor is Gotham City Comics.

We now seem to be on a third different planet from the two previous ones we were on in Astoria and Roosevelt Island…

Above: Sutton Clock Shop, NW corner Lex and East 61st. The shop is operated by 94-year-old [as of 2010] Knud Christenson and his son, Sebastian; the shop has been in this location since 1965, after it opened in the 1940s.

[Clock stores like this have to have all their clocks manually rewound twice a year for daylight savings time and eastern standard time.]

I took this picture of the north side of East 57th from Lex because I saw that vertical Hammacher Schlemmer sign and assumed it was an old one and they were no longer there. Turns out they are. The store features specialty gifts and has been in existence since 1848, and has published a catalog since its first year in business.

In a stretch of Lex that seems to feature all late 20th Century buildings, here’s an odd Deco at East 52nd. Jean-Louis David is a chain of hairdressers, all of whose stores have an exaggerated Century-font logotype.

Doubletree Metropolitan Inn, East 51st. It’s an example of 1961 architecture and was built as The Summit Hotel. We’re in a long stretch of Lexington Avenue hotels dominated by the queen of all NYC hotels, the Waldorf-Astoria, on the west side of Lex between East 49th and 50th.

General Electric Building, a.k.a. the RCA Victor Building, SW corner East 51st and Lex.

Combining soaring verticality and decorative Gothic intricacy, the RCA Victor Building reflected the tone of nearby St. Bartholomew’s Church.

The wide base is a sophisticated piece of the street-level landscape, while the tower is truly one of the jewels in Manhattan’s crown. The lobby is equally spectacular, with its terrazzo floors, purple marble and silver barrel-vaulted ceiling.

The entire composition was designed to reflect RCA’s business — radio — an intangible entity. This soaring tower and lobby with its severe vertical lines symbolizing broadcast signals makes the intangible tangible. As the Woolworth Building was a “catherdral of commerce”, the RCA Building became a cathedral dedicated the new power of radio.

After RCA left the building for its new quarters in Rockefeller Center, the building was renamed for its new tenant, General Electric. The name remains, although General Electric also vacated the building in a move further uptown. Daniel’s Manhattan Architecture

The General Electric Building was built in 1931 and even the subway entrance sign wants to get into the Deco mood.

The Benjamin, opened in 1999, is a luxury hotel in this 1927 high rise designed by Emery Roth, a prolific Hungarian-American architect who masterminded some of NYC’s most prominent residential buildings: The Warwick Hotel, The Beresford, the San Remo, and the Eldorado (the last three featuring prominent twin towers). The Benjamin was originally the Hotel Beverly.

If you ever stay at the Waldorf, don’t forget to look for the elephants across the street. This is yet another Emery Roth work, built as the Montclair Hotel in 1928 and now W New York. Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin got their start here in the late 1940s.

There’s good news regarding the elephants — till recently, they were dirty and encrusted with exhaust grime, but the W has spiffed them up and repainted them light brown. They were originally used as flagpole stanchions.

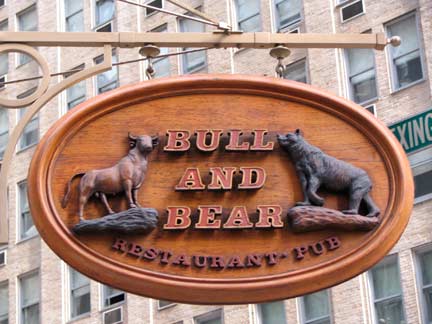

Lexington Avenue is a veritable menagerie if you know where to look. The Bull and Bear occupies the SE corner of the Waldorf.

Marriott East Side, opened in 1924 as The Shelton at Lex and East 49th. The architect was Arthur Loomis Harmon.

Painter Georgia O’Keeffe lived here with photographer Alfred Stieglitz from 1925-35; both made use of their 30th floor view in their art. In August 1926, Harry Houdini was soldered into an iron coffin and lowered into the basement swimming pool; he stayed submerged for 91 minutes. NY Songlines

Hotel Roger Smith, a 1925 hotel designed by Denby & Nute. I’m unsure who Roger Smith was, but the hotel wasn’t named for Ann-Margret’s longtime husband.

At the Grand Central Terminal entrance at Lexington and East 44th stands one of GCT’s original ornamental eagles. This one was discovered by railroad historian Dave Morrison at a home in Bronxville, NY. Morrison and the home’s owners waged a successful campaign to have the eagle placed here.

The Graybar Building abuts Grand Central Terminal as well as the Grand Hyatt (formerly Commodore) Hotel on Lexington Avenue across the street from the Chrysler Building. The Graybar was originally named the Eastern Offices Building. It was designed by the architectural firm of Sloan and Robertson and opened in 1927, at the height of the Art Deco period, and the building was designed with a lighthearted feel.

Above one of the entrances at 43rd Street, a handsome canopy protects people waiting for taxicabs. But what are those bumps on the struts holding the marquee in place? Those aren’t bumps–those are rats! What in the world are carved rats doing on a NYC building: haven’t we got enough real ones? A close look will also reveal eight rats’ heads surrounding each hawser (the lines holding the canopy) as they reach the Graybar Building.

Why the external myomorphic theme, then? Neighboring Grand Central as it does, the Graybar’s architects wanted to emphasize NYC’s status as a great port, and chose to use rats, so often found on sailing ships of yore, to symbolize a maritime theme. Albatrosses also show up in the ornamentation, and formerly, the building’s brass signs above its subway entrances sported seahorses.

10/25/10

1 comment

Growing up in northern Westchester County, a D’agostino’s was my hometown supermarket until it closed at some point during my middle or high school years. Still a few sticking it out in Manhattan, though.