It had been quite awhile sine I had taken a long ramble in the Fifth Borough, apart from some wanderings from the ferry along Kill Van Kull to Snug Harbor, so I took a few hours in July 2012 to travel from Oakwood Heights through Lighthouse Hill and around again to Richmondtown, a location almost smack in the center of the island. Oakwood Heights is almost unknown to anyone but its local denizens, but it is the 10th station away from the ferry and is easily reachable in about a 15-minute ride.

The neighborhood is primarily known for the Great Kills Park Gateway National Recreation Area, accessed from Hylan Boulevard and Buffalo Street. On this trip, though, I struck off north from the SIR station on Guyon Avenue. The neighborhod is more properly called Oakwood and only the SIR calls it ‘Heights.’ The nearest Heights are in Lighthouse Hill, which we will see.

GOOGLE MAP: OAKWOOD HEIGHTS TO RICHMONDTOWN

The Oakwood Heights Staten Island Railway station is one of the ones that was sunk in an open cut in the early to mid-1960s, when all stations were grade-cross eliminated. Notice the date 1963 chiseled in the station house over the tracks.

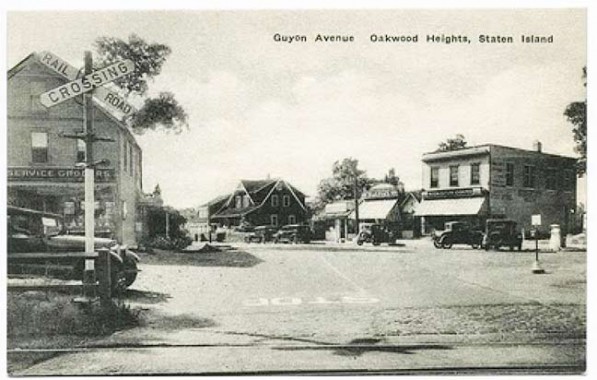

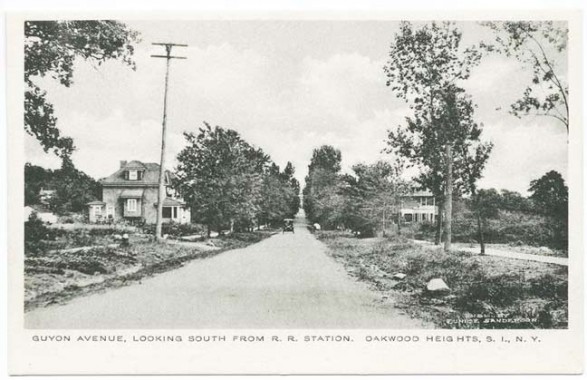

This is the view looking northwest on Guyon Avenue from the railroad at about the same spot with about 90 years between them. I don’t know if the buildings shown on the right are the same — they could be.

There are a number of streets in Staten Island with French-sounding names. In the colonial era, French and Belgian, or Walloon, Protestants (who called themselves Huguenots) settled extensively on the island. The Guyons were one of those families.

Guyon Avenue looking south. Major streets in the area began to appear in the 1890s as the old farms gradually became neighborhoods with a rough grid street pattern.

Oakwood features a great gash of green, a corridor park running from Great Kills Park north past Richmind Road and joining Latourette Park north of Lighthouse Hill. In the 1960s, land was taken by eminent domain, houses were cleared, and Riedel and Combs Avenues were built as service roads for a southern extension of Willow Brook Expressway (Martin Luther King Jr. Expressway) which today connects the Bayonne Bridge and the Staten Island Expressway, reaching its southern terminus at Victory Boulevard. Constructing it would have cost part of Willowbrook, Latourette and Great Kills Parks. Near Raritan Bay, it would have run into another proposed and unbuilt road, Shore Front Parkway, which would have run along the water’s edge from New Dorp Beach to Tottenville.

By the mid-1970s, fiscal and environmental concerns had shelved both roadways.

The unbuilt Willowbrook Parkway section between Rockland Avenue (Lighthouse Hill) and Hylan Boulevard is now the White Trail of the Staten Island Greenbelt trail system and is called the Amundsen Trailway, named for Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen (1872-disappeared 1928). During his career he reached both poles (he led the successful search for the South Pole in December 1911, and was the first expedition leader to attain the North Pole, in 1926) and in 1905 was first to discover the famed Northwest Passage, sought by mariners for over 400 years at that point. He perished while taking part in a rescue mission in 1928.

Amundsen Plaza, at Amboy Road and Clarke and Riedel Avenues, was acquired for parkland by the City in 1929; in 1933, the Norsemen Glee Club of Staten Island and the Norwegian Singing Society of Brooklyn placed a tablet on this site in honor of the pioneering Norwegian explorer.

The tablet is now visible again — in the past, it had been obscured by vegetation.

There is an Amundson Avenue in the northeast Bronx, but it is named for a real estate developer.

Alarm Clarke. One of the newer fire alarm stanchions (about 1972) with police and fire call buttons from the 1980s, on Amboy Road and Clarke Avenue.

Amboy Road, shown here at Montreal Avenue, is the main road running through the center of southwest Staten Island, splitting from Richmond Road in New Dorp and going several miles to the Arthur Kill.

The origin of the name “Amboy” of Amboy Road and Perth Amboy, NJ is hard to pin down. It can derive from a number of Dutch terms — “een boge,” or bow, perhaps describing the curve of the Arthur Kill, or “am bog,” elbow (the mysterious word “akimbo” is likely a contraction of “in a keen bow”), or, perhaps, “het ambacht, “(“the hundred”) or the Malaysian island of Amboyna, an outpost of the Dutch East India Company, site of an infamous massacre in 1623. Brooklyn’s Amboy Street was the setting for Irving Shulman’s 1946 novel about a street gang, The Amboy Dukes – later used by Ted Nugent’s band The Amboy Dukes who hit with the classic Journey To The Center of The Mind in 1968. Other sources, like Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss’ Brooklyn By Name, when referring to the borough’s Amboy Street, posit that it has Algonquian origins.

Though Amboy is a modest two-lane road here, it occasionally get wider and can be as many as four lanes across.

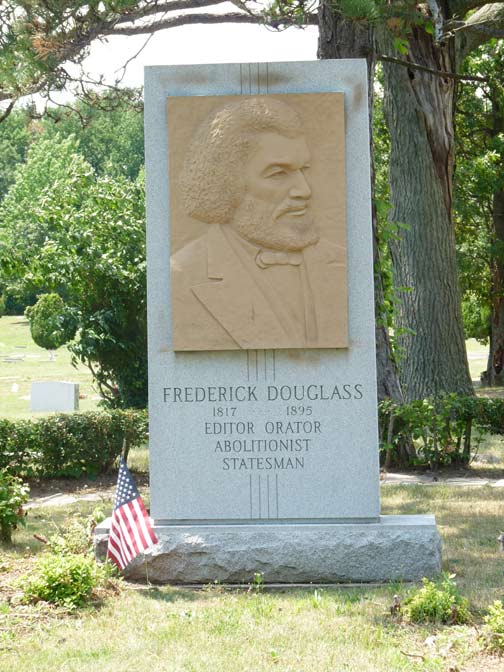

On the northwest corner of Amboy Road and Montreal Avenue is the entrance to Frederick Douglass Memorial Park. The cemetery opened in 1935 and was used solely by African-Americans in the segregation era. Today, it’s open to all colors, nationalities and faiths. Just within the front gate is a memorial to the great orator, writer, editor, and abolitionist (1818-1895)

On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped slavemaster William Freeland by boarding a train to Havre de Grace, Maryland. He was dressed in a sailor‘s uniform and carried identification papers which he had obtained from a free black seaman. He crossed the Susquehanna River by ferry at Havre de Grace, then continued by train to Wilmington, Delaware. From there he went by steamboat to “Quaker City” (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and continued to the safe house of abolitionist David Ruggles in New York; the whole journey took less than 24 hours.

Frederick Douglass later wrote of his arrival in New York:

“I have often been asked, how I felt when first I found myself on free soil. And my readers may share the same curiosity. There is scarcely anything in my experience about which I could not give a more satisfactory answer. A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the ‘quick round of blood,’ I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. It was a time of joyous excitement which words can but tamely describe. In a letter written to a friend soon after reaching New York, I said: ‘I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.’ Anguish and grief, like darkness and rain, may be depicted; but gladness and joy, like the rainbow, defy the skill of pen or pencil.” wikipedia

When happening on this memorial park, many are surprised to learn that Douglass is not interred here. His remains are in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, NY, where he resided from 1843-1872.

It’s a pleasant side street in a suburban neighborhood, but Fairbanks Avenue illustrates an odd occurrence in Staten Island street naming philosophy: there are a number of streets with Alaskan-themed names scattered around the borough, from this to Alaska Street in West Brighton to Klondike, Nome, Yukon, Platinum in Heartland Village. Can anyone shed a light on why this is?

105-acre Ocean View Cemetery, formerly Valhalla Burial Park, faces Amboy Road at Hopkins Avenue. It is part of mid-Staten Island’s mini cemetery greenbelt, bordering Douglass Memorial Park and United Hebrew Cemetery. The all-faiths cemetery has been open since about 1900.

Perhaps Ocean View’s most noteworthy feature is its Gothic stone chapel and clock tower.

It’s a monument stone business. No, it’s a Louie G’s ice cream parlor. Relax– on Amboy Road opposite Ocean View, it’s both. This is one of the most unusual dual-use buildings I’ve ever seen.

Across Hopkins Avenue is J.L. Wegenaar, which its sign says was founded in 1872 and celebrates its 140th anniversary in 2012.

Heading up Clarke Avenue, a direct route to Lighthouse Hill and Richmondtown, I noted a vast panoply of building styles. Needless to say most of the uglier ones were the latest ones. Somebody thinks that thing with the white and gray bricks is the cat’s meow.

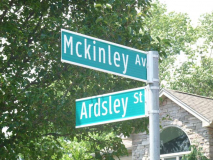

McKinley Avenue runs north-south between Clarke Avenue and Richmond Road. At either end, it’s marked by handsome cobblestone gateposts, which indicate that long ago, it was part of a private development. I haven’t been able to find out what it was, though.

The Department of Transportation spells McKinley Avenue in a creative variety of ways. It’s a good bet that the road was named for President William McKinley (1843-1901), so that spelling is probably the right one.

McKinley Avenue is dominated by a large conifer.

[In Comments], name those cars. One is a Caddy, the other is a Lincoln, that’s all I know.

Lighthouse Avenue at Richmond Road features another pair of mysterious gateposts labeled “Lighthouse Hill.”

I should someday do a page on Staten Island’s hidden, or unmapped, creeks, which are numerous in the southern half of the island. (Several years ago I covered Lemon Creek in the Prince’s Bay neighborhood.)

Though Richmond Creek arises in Ohrbach Lake (which is indeed named for the old Ohrbach’s Department Store) in the Pouch Boy Scout Camp in the Todt Hill area, it flows in a trickle through the Lighthouse Hill area before getting much wider in Latourette Park in the west.

Before turning east and climbing Lighthouse Hill in earnest, Lighthouse Avenue passes #442, a picturesque cottage dubbed by its owners “Lighthouse Garden.” it features well-maintained topiary.

This house at the curve appears to be built into the side of the steep hill.

Staten Island’s hills are among the highest on the east coast. Lighthouse Avenue is the only through route for travelers hoping to climb Lighthouse Hill to Rockland Avenue, which connects New Springville and the New Dorp area.

This fork is the intersection of Lighthouse Avenue and Manor Court (right). Visitors like myself were once able to ascend Manor Court to see the famed buildings at the top of its hill (see below); local property owners fenced it off, probably to keep the hoi polloi from doing just that.

Who would ever think that Staten Island would be the world’s capital of artwork collected from Tibet? It’s all because of Edna Coblentz (1887-1948) who became an art dealer in Manhattan after her acting career stalled. As a child, Edna had discovered thirteen Tibetan figurines in an attic trunk; her grandfather had brought them to the USA from an Asian trip, and she became fascinated with Tibetan artwork. She had moved to Lighthouse Hill with her husband, Harry Klauber, in 1921. After some years exhibiting on 51st Street in midtown, Edna, who adopted the nom de plume Jacques Marchais, financed the construction of the Museum of Tibetan Art at 338 Lighthouse Avenue built to resemble a Buddhist temple, with meditation gardens and a lotus and fish pond which also contain a large turtle or two. The primary collection is Buddhist art from Tibet, Mongolia, and northern China from the fifteenth to early twentieth centuries, including paintings, ritual artifacts, figurines, musical instruments, and historic photographs. In June 1991, the Dalai Lama was an honored guest.

After Jacques and her husband passed away in the late 1940s, their friend, Helen Watkins, took over the museum, which has been maintained privately since then with the aid of government grants and admission fees. The Museum is open to the public every Wednesday through Sunday from 1:00 – 5:00 PM. For information, call (718) 987-3500 or check www.tibetanmuseum.org.

A model airplane has found its way onto a tree stump opposite the Tibetan Museum. The Staten Island Mall was built just to the south of one of Staten Island’s lost airports, and just to the east of another one.

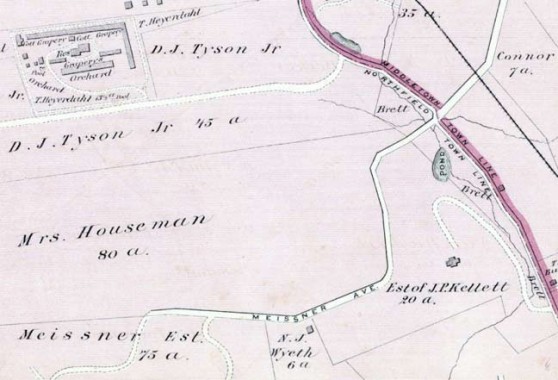

This 1874 atlas plate shows the northern end of Lighthouse Hill. Lighthouse Avenue continues east, makes a turn to the north, becoming Terrace Court, and then a turn to the east becoming Meisner Avenue, which continues on to the intersection of Rockland Avenue and Manor Road, where the motorist can continue on to New Springville or following Manor Road, arrive in Four Corners and West Brighton. On the map you can see Meissner Avenue with two S’s snaking its way up the hill; the Meissner family owned property in the region.

Notice the buildings shown in the upper left. In the early 1800s, the Heyerdahl family attempted to establish a winery and built a grape orchard, but gave up on the plans. Ruins of the Heyerdahl works can still be spotted on a Greenbelt trail in the middle of Latourette Park.

We are almost at the summit of Lighthouse Hill along Meisner Avenue.

Some of the suburban homes lining Meisner Avenue.

Just one of the buildings that comprise the Eger Medical Center on Meisner just before it reaches Rockland Avenue. It provides a range of services including Social Adult Day Care, residential care, and specialized nursing.

Eger has a lengthy and rich NYC and Staten Island history. Carl Michael Eger (1843-1916) was a Norwegian-born, German-educated architect. His Hecla Iron Works built the spiral staircase of the Statue of Liberty, and it provided the ironwork for NYC’s Hotel Pennsylvania and the US Treasury Annex in Washington, among other structures.

When Eger passed he left an estate of $1 million, of which $60,000 was designated for the care of elderly Norwegians. His home on Pulaski Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn was converted to the first Eger Norwegian Lutheran Home for the Aged. After a larger facility was needed, the Eger Home moved to Lighthouse Hill in 1926. The Eger’s services are now, of course, available for all nationalities and religions.

Nearby Scheffelin Avenue and Esther Depew Street. An internet search has come up blank about who Esther Depew was — any Staten Islanders have any idea?

As Yogi says, when you come to a fork in the road, take it. I needed Edinboro Road (left)at Meisner Avenue for the next highlight on this walk. There are a pair of roads in the area called Edinboro and London, so there must have been some Britishers settling the area in the early 20th Century.

The roads in Staten Island Hills are often the repositories for experimental housing styles, some of which are more successful than others.

Staten Island has several land-anchored lighthouses (Brooklyn and the Bronx have once apiece, and Manhattan’s is on Roosevelt Island). The Staten Island Lighthouse, built on Edinboro Road from 1907-1912 and operating since 1912, is one of Staten Island’s architectural treasures. Here it stands next to a rather ugly latterday object.

In its early days, the lighthouse keeper kept oil-powered pumps going to operate the lens. Horse-drawn carts needed to make the arduous climb up the hill, whose difficulty was exacerbated by snow and ice in the winter. Today, a 2nd order Fresnel range lens it acquired in 1939 sends a beam 18 miles into Lower New York Bay that lines up with the West Bank Light off South Beach. It is run by the US Coast Guard today and is now fully automated.

In 1912, the New York Times wrote that the Staten Island Lighthouse was “destined to take its place among famous beacons of the world, such as Eddystone Lighthouse, on the Eddystone Rocks, about fourteen miles from Plymouth, England.”

The old lighthouse keeper’s house next door has been renovated in recent years; it initially had the same bricked exterior of the lighthouse itself. Oddly, it shares a gate with the lighthouse, so the now-private dwelling’s owner has to deal with the occasional outsider and lighthouse maven snooping about.

Walking south on Manor Court, an arresting look down the hill into Richmondtown is available from the driveway of a private dwelling. The spire belongs to St. Andrew’s Church, which will be visited in Part 2.

This beautiful building, #48 Manor Court, is Frank Lloyd Wright’s sole private home design in New York City, yet he never saw its completion, as it was finished the year he died, 1959. Wright did plan to visit the construction site in 1958 but illness kept him away.

The lengthy red and tan building is at the edge of Lighthouse Hill, 200 feet above sea level, and takes full advantage of the spectacular hillside and ocean views. It is in the mold of Wright’s famed “prairie” design ranch houses. The building was commissioned and built for New York personnel agency vice-president William Cass and his wife Catherine, who occupied it for forty years, selling it in 1999.

The Casses were fans of Wright’s work elsewhere in the country, and after seeing him on a Mike Wallace interview show in 1957, wrote the architect to inquire if he would build a house for them. Wright referred them to an associate, Marshall Erdman, a Lithuanian-born architect, who agreed to construct a design called “Prefab N. 1.” Prefabricated units were shipped from Madison, Wisconsin, and assembled here by another Wright associate, Morton Delson, who sited the house for maximum views of the valley and Richmondtown below.

The house is named for a copper beech tree that originally graced the property. A 1967 hurricane felled the original tree, but a new one was planted in its place.

Wright, who believed that a building’s interior furnishings should be designed in concert with the exterior, also designed the living room and bedroom furniture. A swimming pool was added in the 1960s as a break against forest fires on Lighthouse Hill.

Other Wright designs in the NYC area include the Solomon Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue and East 89th Street, a Mercedes-Benz auto showroom at 430 Park Avenue, and the Ben Rebhuhn House in Great Neck Estates.

Living with Frank Lloyd Wright [NY Times]

Mike Wallace interview with Frank Lloyd Wright:

Returning to Edinboro Road, it runs west through the woods and emerges at Latourette Golf Course, whose clubhouse is a historic building in its own right.

This Greek Revival residence was built in 1836 for David Latourette (1786-1864) a prosperous farmer and a descendant of one of the French Huguenot families who had settled Staten Island in the colonial era. The family operated a farm here until 1910 and sold the property to the City in 1928. It then became the golf course clubhouse as part of a Works Progress Administration project in 1934. The side porch was added in 1936.

PART 2: down Snake Hill to Richmondtown

SOURCES:

Richmond Town and Lighthouse Hill, Margaret Lundrigan Ferrer, 1996 Arcadia

Lighthouses of New York, Jim Crowley, 2000 Hope farm Press

Realms of History: Cemeteries of Staten Island, Patricia M. Salmon, 2006 Staten Island Museum

Jean Siegel provided older photos

8/6/12

10 comments

The Cadillac is an ’80-’84 Coupe de Ville and the Lincoln is a Town Car. I’m guessing an ’85, but can’t be sure without seeing the taillights.

The Caddy is a 1981 as evidenced by the plate on the front quarter panel advertising the V8-6-4 engine available in 1981 only. In theory the engine would run on 8, 6 or 4 cylinders depending on the car’s speed, load, etc. The engine proved very troublesome and GM discontinued it after one year (and more than a few lawsuits). The Town Car is indeed a 1986-88, which can only be distinguished by slightly differing tail lights and rear trim.

As usual Kevin, an excellent overview of a little noticed and lovely area of Staten Island. It’s really hard to believe you’re in NYC judging by these pics.

I remember that Amboy Dukes album cover.It had about 20 exotic little pot pipes arranged in rows on it.

I once had a conversation with Cathy Cass back around the late 1970s-early 80s re her Frank Lloyd Wright house. She noted two things: that her house shared a common flaw with other Wright houses — leaky roofs, and a funny conversation she had with him. Apparently he said when describing a Gallery room or hall in the house something like “and here’s where your collection of Chinese porcelains will be displayed” and she said “I don’t have Chinese porcelains,” to which he replied “you will.”

Yes, Wright buildings are noted for having leaky roofs….

If you’re interested in exploring the hills of Staten Island, I have a suggestion for one you may not have discovered yet (Forgive me you already have. You website is – happily – so extensive I haven’t read the whole thing yet.). Snaking down from Howard Avenue (starting near Wagner College) to Van Duzer Street on the eastern side of the island is Signal Hill Road. I remember as a kid being told it was so named because Native Americans used to light signal fires at the top of its location back in the day. whne you go there you can see why. It has a commanding view. It’s a very winding very steep road that has some absolutely charming houses on it. One little stone house with a window in the form of a spider web has always been my favorite. If you haven’t been there yet, it’s totally worth the trip. Not only that, but Howard Avenue offers stunning panoramic views of the whole of New York Harbor all the way through the Narrows and out into the Atlantic. Enjoy!

One more hill comment. If you haven’t already been definitely check out Emerson Hill right off the expressway at Clove Road. It also has some extremely charming houses. It’s so out of the way development seems to have left it alone to age graciously.

Kevin, this Forgotten piece was a breath of fresh air, punctuated by the interview with Frank Lloyd Wright (who uttered many of my lifelong sentiments). Until your forays into Staten Island, I knew very little about the borough beyond the C.U.N.Y campus and Clove Road condos. So glad you posted this one; on to Part 2.

As a Scandinavian American and second generation American and Islander, it saddens me that there is so little acknowledgment of the participation of Norwegians and Swedes on this Island. I just laid my mom to rest, born in 1925 to a Norwegian Sea Captian and Swedish immigrant who settled in Eltingville. She was buried in Ocean View cemetery, Oakwood. It was originally called “Vahalla,” which was the name of the afterlife rearing place of Viking warriors. I can find no history about the origins is this cemetery, no doubt founded by my people Many Scandinavians couldn’t tolerate the business of the other boroughs and sought the more familiar natural surroundings of their homelands in Staten Island. Eltingville was a strong Scandinavian stronghold. Sadly we are not an outspoken people and are history is unknown. I plan on bringing us to light! I am tolerant of all people but would like to see kone remembered as well. Time to get assertive about our history — not a cultural characteristic. I am so proud of my mom dad and ancestry. We are an admirable people

Right next to the Tibetan Art museum at 340 Lighthouse Ave is this funny little house, built by Jacques Marchais herself. It has some unique features and a fabulous grounds. Supposedly built in 1921.

https://streeteasy.com/sale/1313265