Woodside is often the jump-off point for some of my lengthier walks. The reason is simple. It’s the westernmost Long Island Rail Road stop in Queens (on my branch, that is; there are stops at Hunters Point as well as Long Island City that are only used weekday rush hours). Thus, I set off for a lot of walks from Woodside, heading toward Astoria, Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, Corona, Maspeth and even Ridgewood from Woodside. This was a clear day in April and the temperature is still livable this time of year, so I just kept going and going, for about 9 or ten miles over about four or five hours, finally reaching Bedford-Stuyvesant in late afternoon…

Google Map: Woodside to Bedford-Stuyvesant

According to historian Vincent Seyfried in Old Queens, NY in Early Photographs, the Woodside Court, 39-70 62nd Street (a dead end north of Woodside Avenue by the LIRR) is the oldest apartment building in the area. It was constructed soon after the LIRR was rerouted and the present Woodside station was built, which combines access to Main Line LIRR, Port Washington LIRR, and the #7 Flushing el. The building has some interesting brick detail, diamonds, arches and such.

Though the railroad has been diligent about expunging references to Shea Stadium, which was demolished in 2009, they forgot about this sign on 62nd Street, which will likely be duly replaced once the word gets out. (The MTA has kept “Shea Stadium” signs in place at the #7 subway station there).

This pair of handsome brick buildings on 62nd Street south of Woodside Avenue are today associated with the Mormon Church, but until 1993 they were part of a watchmaking school founded by Arde Bulova in 1944. The Church of Latter-Day Saints acquired the buildings in 1997. The Bulova Watch Company formerly had its national headquarters in Long Island City, but has now moved most of its staffers to the Empire State Building.

I wish all of NYC’s fire alarms could be maintained like this one at Woodside Avenue and 61st Street — in recent years, someone has given it a fresh coat of red paint, with silver highlights. The shaft at the top used to hold a red glass globe in which was held the indicator lamp.

One of Queens’ more obscure dead ends, Mackintosh Street, is on 63rd Street just north of Queens Boulevard. It serves as a driveway and parking lot for adjoining buildings.

One of Queens’ more obscure dead ends, Mackintosh Street, is on 63rd Street just north of Queens Boulevard. It serves as a driveway and parking lot for adjoining buildings.

The street sign had disappeared by 2015.

The most prominent sight walking south in Woodside is the presence of the Big Six Towers, located between 59th and 63rd Streets, Queens Boulevard and 47th Avenue. They were developed, like Electchester in Flushing, by a trade union. The New York Typographical Union (Local 6) largely funded the project, completed in 1963, and at one point, one-third of its tenants are active or retired union members. The AFL-CIO invested heavily in the towers in 2008 to help keep its apartments affordable for middle-class families.

Bush Park, along 61st Street and Laurel Hill Boulevard (the service road for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, is not named for the prominent political family (which is centered in New England, Florida and Texas, anyway) but because until about 30 years ago (in 2015) the stretch of 61st Street that is accompanied by a ramp connecting Queens Boulevard with the BQE was called Bush Street.

The streets in the 60s south of the BQE and north of Mount Zion Cemetery feature handsome attached brick buildings constructed in the days when front lawns, or areas of green, were still important elements and developers still included them.

Mount Zion, a Jewish cemetery, occupies about 80 acres in Maspeth near New Calvary Cemetery and the BQE. It was opened in the early 1890s under the auspices of Chevra Bani Sholom and later by the Elmwier Cemetery Association (Elmwier Avenue is a former name of 54th Avenue).

A walk in Mount Zion will produce a surprising and poignant reminder of burial practices long forgotten… the faces of the dead are preserved on some of the tombstones. I’ve shown several of these on my Mount Zion Cemetery page.

The twin smokestacks are currently on the grounds of the NYPD Fleet Services Division.

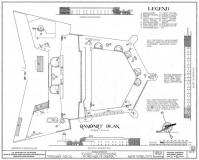

Like a number of other cemeteries in New York City, Mount Zion incorporated an older cemetery when it was founded. The odd-shaped plot in the center of this aerial view is the family plot of the Betts family. Captain Richard Betts (1613-1713) and wife Joanna’s home stood at the southwest corner of territory now surrounded by the cemetery. It was razed in 1899. According to legend, Captain Richard Betts dug his own grave in the Betts family plot a few days before he died. His grave is not detectable but many of his descendants’ are.

Brooklyn’s Prospect Park even includes a Quaker cemetery that was in place before the overall park was completed in the 1870s!

Seen on the far left in this view across the cemetery are the twin towers of St. Aloysius Church on Onderdonk Avenue, the tallest building in Ridgewood, Queens. Through the trees you can see a tall, narrow shaft, which is 432 Park Avenue, the tallest residential tower in the western hemisphere — though it is due to be surpassed within a few years!

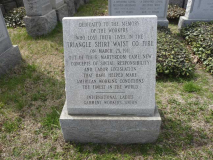

Accessible via a short walk inside the Mount Zion Cemetery entrance gate on Tyler Avenue just off 63rd street is the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial.

On Saturday, March 25, 1911, as quitting time approached at the factory building still standing on Washington Place in Manhattan, a fire broke out on the eighth floor of the Asch Building (now the Brown Building) and spread rapidly on the top three floors . In a scene reminiscent of the General Slocum tragedy 7 years before, fire hoses were woefully inadequate to battle the flames, the lone fire escape was rickety and rusted, and the doors to the exits were locked to insure that the mostly immigrant women working the sewing tables would not wander or steal anything.

There was little escape from the flames and the mostly immigrant women working the tables were forced to jump out of windows or burn to death, and many chose the former. While some were able to escape by an open staircase and an elevator, 145 employees would perish. In less than a half hour, the fire was brought under control. Triangle owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck were charged with manslaughter; after a two-week trial they were found innocent.

Three years after the fire, on March 11, 1914, twenty-three civil suits against the owner of the Asch Building were settled. The average recovery was $75 per life lost.

A view across Mount Zion from Maurice Avenue. One Hanson Place, the former Williamsburg Bank Building, looms over. It is no longer the tallest building in Brooklyn, but it’s still the most recognizable.

A handsome Tudor-flavored building at 53rd Avenue and 64th Street, a couple of blocks from Mount Zion Cemetery.

Here, the hill is too steep for a road, and a staircase assumes 53rd Avenue’s role eastward to what is called the Ridgewood Plateau, even though we are in northern Maspeth, not Ridgewood. The name is the dream of a long-ago real estate developer, Realty Associates, which purchased 70 acres in 1928 in what was then called North Ridgewood.

The walkway is lit by Type A & B park posts, and amazingly, what is Maspeth’s only object recognized by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, a surviving original Type F lamppost that had likely survived only because no person of any importance in the Department of Transportation noticed it was there. After it was landmarked, it was refurbished. Other surviving Type F posts can be found along Shore Parkway in Brooklyn and on West 13th Street in Greenwich Village, though new versions have been installed on West 8th Street and on Wyckoff and Metropolitan Avenues.

A much larger Tudor-style apartment house can be found at the top of the staircase at 65th Place, a main north-south route, and 53rd Avenue.

One of Maspeth’s most popular watering holes is O’Neill’s at 65th Place and 53rd Drive. Established in 1933, the steakhouse hosted the New York Mets after their 1986 World Series victory. It has rebounded after its destruction in a 2011 fire.

One of the “named” Queens dead-ends I haven’t yet remarked upon is Claran Court, on 65th Place near O’Neill’s. The court is shown on Queens maps as early as 1938, so we can assume that its uniform layout of homes were developed in the mid-1930s.

A quartet of concrete and iron “Ridgewood Plateau” signs, dating back to the original development of the parcel by Realty Associates in 1928, survive on both sides of 65th Place at Maurice Avenue at the north side and at Jay Avenue on the south side. In the fall of 2014 the pair at Jay Avenue were restored with the assistance of the Juniper Park Civic Association, the Newtown Historical Society, Maspeth Federal Savings, the Communities of Maspeth and Elmhurst Together and O’Neill’s Restaurant. Woodside artisan Larry Madine re-inscribed the the words “Ridgewood Plateau” in gold leaf on the sign on the west side of 65th Place.

The gateposts are of historic interest, as well, because they preserve 65th Place’s original name, Hyatt Avenue.

The complicated intersection of 65th Place, Hamilton Place, and 55th and Borden Avenues at the Queens Midtown Expressway creates a number of traffic triangles, which have names I like to call “Henry Stern-isms” after the colorful Parks Commissioner under the Giuliani administration in the 1990s; he often bestowed colorful names to squares and parks that had previously been unnamed. One of these is Federalist Triangle, where Hamilton Place meets Jay Avenue. High school history A students will remember that the Federalist Papers were a series of articles written by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison promoting the ratification of the United States Constitution.

Another small park on the site, Cowbird Triangle, is named for the confluence of Borden and Jay Avenues. The reason is simple. “Cow” is for Borden, whose spokescow for decades has been Elsie, who made her debut at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, and “Bird” is for Jay Avenue.

Cowbird Triangle acquired a second name a few years ago when the name of a Maspeth World War II hero who received both the Bronze Star and Silver Star posthumously after he was killed in action in France in 1945 was appended to it.

Since I had not used it for several years I decided to cross the Queens Midtown expressway using the 61st Street pedestrian bridge, which rises so high it needs lengthy spiral ramps at both ends to access it. Davit (curved-mast) lampposts are used.

I was able to get this shot of the Kosciuszko Bridge by pointing the camera west on 55th Drive. The name is used alternatively with Borden Avenue, the service road of the QME. The bridge opened in 1939, but preparations for the construction of twin cable-stayed spans that will replace it by the end of the 2010s are already underway.

The building to the right of the bridge is the 1926 Con Ed Headquarters clock tower on East 14th Street and Irving Place.

The spiral ramp on the south side of the QME is lit by octagonal shafted “World’s Fair” lampposts; the spiral is centered by an unusual concrete structure — I don’t know if it once had a purpose or if it’s purely decorative.

At the back end of Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church on 56th Avenue is a grotto celebrating the virgin Mary, mother of Christ, a common scene at Catholic churches the world round.

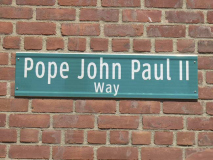

Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church on 56th Road between 61st and 64th Streets may take a back seat to the nearby Church of the Transfiguration as far as flash is concerned, but the parish, established in 1912, is one of a few in northern Brooklyn and southwest Queens to have been visited by Cardinal Karol Wojtyla before he ascended to the papacy and became known as John Paul II in 1978.

The church message board is punctuated with Polish translations of English listings.

When JPII was canonized, or made a saint, in 2014, the block was sub-named Pope John Paul II Way, and in an unusual situation (I haven’t seen it before elsewhere) most of the private homes on the street have hung a Department of Transportation-issued Pope John Paul II Way street sign.

As early as 1890, Polish immigrants chose Maspeth in which to settle. In 1921, the Polish National Home, 56th Road and 64th Street (or in Polish, “Polski Dom Narodowy”) was founded in order to teach younger generations about their Polish heritage. This building was erected in 1934. Members of this organization helped to build the 1939 World’s Fair, dedicated Maurice Park and participated in the opening of the Kosciuszko Bridge in 1939.

History of the Polish Community in Maspeth [Juniper Civic]

From here, the back end of the Church of the Transfiguration can be seen.

In Part 2: Maspeth into Ridgewood

6/7/15

5 comments

You can order a street sign from the NYC DOT shop in Queens. I have a S.I. street sign in the original borough colors of black on yellow which I have in my garage in MD.

Hey that’s cool.

Here’s the link:

http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/html/infrastructure/custom-signs.shtml

My mom’s side of the family(some of them) are in Mt.Zion-some of them have those enameled photos including an aunt I never knew who died at 21-her photo was on the wall over my bed as a kid and it was strange the first time i saw it in the cemetery.

My grandfather,who died young also,belonged to one of those old country burial societies-he came here around 1900.

The twin smokestacks behind Mount Zion are a NYC Sanitation facility, the Woodside Incinerator in use until the 1980s and still used as a Sanitation garage.

My Mother’s parents as well as some Aunts and Uncles are buried at Mt Zion…