By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

One of the great roads of Brooklyn is Eastern Parkway, a designated city landmark, the city’s first Olmstedian parkway, a ribbon of greenery connecting Prospect Park and Lincoln Terrace Park. At the eastern end of the original parkway at Ralph Avenue, there are no monuments. The parkway loses its distinctive lampposts and green medians as it takes a northeast jog of 1.4 miles towards Bushwick.

This extension of the parkway lacks the beauty and official recognition of Olmsted’s original 2.5 mile route, but that’s what makes it worthy of Forgotten-NY. On that original route, the avenues crossing the parkway are New York, Brooklyn, Kingston, Albany, Troy, Schenectady, Utica, Rochester, Buffalo, and then Ralph. All of them nod to the geography of this state, but the last one isn’t a city. Its namesake is 19th century landowner Ralph Patchen.

Editor’s note: Brooklyn is consistent in one thing: inconsistency. When Flatbush Avenue was extended north to the new Manhattan Bridge in 1909, the extension was labeled “Flatbush Avenue Extension” on street signs, because Flatbush Avenue begins its numbering, running south, at #1 at Fulton Street, while the extension’s numbering is north from Fulton. When Eastern Parkway was extended, its numbering could continue east, and so while maps (older ones at least) call it “Eastern Parkway Extension,” street signs just say plain “Eastern Parkway.” Got it?

Likewise with Pitkin Avenue, which begins its lengthy run towards Ozone Park at Eastern Parkway, behind the trees when looking east from Ralph Avenue. On the map, Pitkin lines up almost perfectly with Olmsted’s original parkway route and looking at maps prior to 1890, this avenue was intended as an extension of the parkway through Brownsville and East New York.

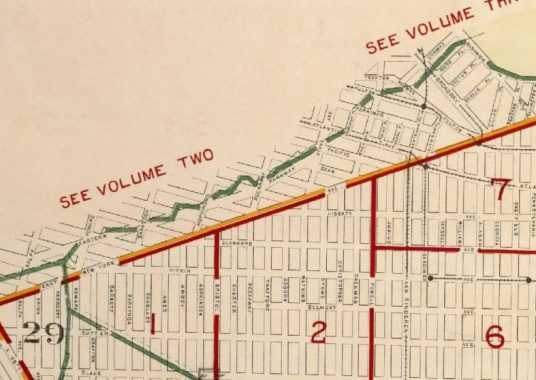

Instead, the extension was given a grid-defiant route towards Bushwick on account of Highland Park, which was acquired by the city of Brooklyn in 1891. Its route follows the former border between Brooklyn and the Town of Flatbush, as seen in this 1904 Belcher-Hyde atlas. That border runs atop the glacial terminal moraine. With this extension, Eastern Parkway would serve as a green ribbon connecting Prospect Park with Highland Park. Some of the city’s greatest landmarks are unfinished and here, Eastern Parkway’s extension is a simple road that terminates a half mile shy of its intended destination.

But it has its unofficial landmarks, many of which are distinguished by their flatiron appearance. At 1403 Eastern Parkway, the Universal Temple Church of God still has a Star of David at its point hinting to its previous owner, Congregation Adath Yeshurun which prayed here until 1970. It was among the last synagogues to vacate Ocean Hill and Brownsville following a decade of urban decay and white flight in this section of Brooklyn.

At Howard Avenue, the parkway picks up traffic from Kings Highway and Lincoln Place has its eastern tip. There’s a nondescript lighting wholesaler here but on the wall facing Lincoln Place is the Studebaker logo hinting of its past as a car dealership. The South Bend-based automaker made its last car in 1966.

At St. John’s Place, Holy House of Prayer for All People occupies a sizable former theater that has a Jewish past. Built in 1929 as the Rolland Theater, it opened at a time when Brownsville had one of the largest Jewish populations in the world. On the High Holidays, this theater was used for prayer services. Local boy Fyvush Finkel got his start here and lived to the age of 93, as one of the last Yiddish actors of his generation. Brownstoner provides a detailed history of this Neo-Moorish building, which became a church in 1956.

Forgotten-NY loves to share the city’s superlatives and if we had to name the city’s narrowest park, the 17 medians on Eastern Parkway’s extension are designated as parkland. Their width cannot accommodate a bench, let alone a tall tree. At the turn of the 20th century, other parkways in Brooklyn such as Rockaway, Bay, and Fort Hamilton, were also under the purview of the Parks Department. Today, the roadways are maintained by the DOT but the trees are planted by Parks. Can such a narrow median have a more parklike appearance?

With enough funding, it can have the look of Park Avenue South, whose median is just as narrow but has plenty of trees and planters. Such a simple beautification could make the parkway extension into a true parkway.

At Park Place is a new affordable housing complex built by Habitat for Humanity. This new building has a backyard on the sloping terrain and wraps around two century-old walk-ups that survived the period of urban decay. Those two have cornices and rundbogenstil arches above their windows. This post-millennial neighbor’s distinctive features are its pop-out square bay windows.

Continuing east to Prospect Place, I initially assumed that Pentecostal House of Prayer is also a former synagogue, but then I spied the initials NSC above its three great windows. There was never a shul with those letters in Brownsville, and an address search revealed that they stand for Nonpareil Social and Athletic Club, which was founded in 1896 and built this fine structure in 1921. I could not find information on when Nonpareil vacated this site or if the club is still in existence.

Having a Jewish membership, Nonpareil maintained a plot at Montefiore Cemetery in Queens. The two walk-ups next to this church have beautiful keystones, symmetrical brickwork, and arched cornices with the names Mountain and Prospect, and their respective years of completion, 1911 and 1910 respectively.

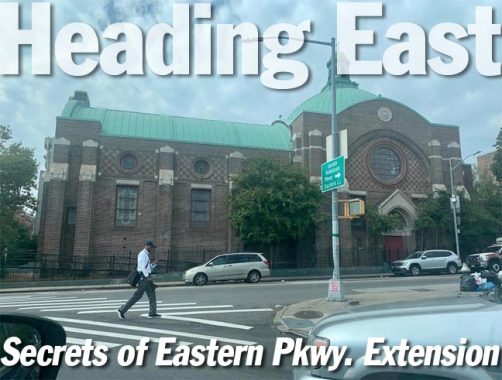

Where St. Marks Avenue and Rockaway Avenue meet Eastern Parkway is the massive neo-Byzantine Our Lady of Presentation – Our Lady of Loretto Roman Catholic Church, its full name reflecting a merger in 2010 that resulted from declining membership across the neighborhood. Its architect, Frank J. Helmle has a diverse Brooklyn portfolio that includes an ornate Spanish Baroque revival church in Bushwick and the Venetian-inspired beaux arts boathouse in Prospect Park.

At Dean Street is another interesting flatiron, with its decorative octagram and floral star inside. This building is triangular, bound by Dean Street, Mother Gaston Boulevard and Eastern Parkway. I initially presumed it was a religious or an ethnic symbol.

At Fulton Street is another historic apartment building, the Oceanic, whose name serves as a reminder that we are in Ocean Hill, a neighborhood that is not exactly Brownsville, nor Crown Heights, nor Bed-Stuy. Prior to urbanization, one could see the ocean from the hilltops here. Until 1956, trains of the Fulton Street El whooshed past these windows. Today one can feel a slight shaking from the subway line that replaced this old transit line in 1940.

Across the street from Oceanic is Callahan-Kelly Playground, which the city acquired in 1938 as part of the Fulton Street subway project. It carries the names of two local men killed in World War One. Truxton Street marks the north side of this park. It was named for Commodore Thomas Truxtun, a veteran the American Revolution and the undeclared naval war in the 1790s against revolutionary France. The street grid of Bed-Stuy and south Williamsburg is a Who’s Who of the American Revolution: Hull, MacDougal, Sumpter, and a dozen other names.

The parkway has its eastern terminus at the highest point of Bushwick Avenue. A few feet shy of its end, Eastern Parkway meets the grid-defiant Cooke Court, which has no addresses on it, and an embankment wall on one side. This wall marks the point where the Canarsie Line, or L subway train, leaves its tunnel and continues its southbound route as an elevated line.

Turning right one would see the Evergreens Cemetery, eventually reach Highland Park, or continue driving to points east on the Jackie Robinson Parkway. To the left, Bushwick Avenue runs through its namesake neighborhood towards East Williamsburg. Continuing straight for one block is the dead-end Vanderveer Street, named after a colonial Dutch settler family that once owned land around here.

As I drive back to my home in Queens, there’s one more curiosity I’d like to share, one block from the end of Eastern Parkway’s extension: President Auto Center on Bushwick Avenue, whose awning features automaker logos alongside heraldry from the flag of Turkmenistan. It’s the only business in the city that I’ve seen that has the flag of this secretive Central Asian nation.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

10/22/20