I am drawn to DUMBO quite a bit, from its stolid brick factory and warehouse buildings…to its water views…to its Belgian blocked streets suffused with ancient railroad tracks. I have worked all over town over the years, and enjoyed by two-month stint at education publisher Amplify in February and March 2015. It was a cold and snowy winter and at lunch hour I was able to squeeze off some spectacular snow shots (seen on this page).

As early as 2013 reports trickled through that the Department of Transportation, especially its then leader, Janette Sadik-Khan, wanted to rip up the street pavement and the tracks. When I got the chance, I thought I’d make my way over to see if anything had happened to them.

Many visitors to DUMBO mistake the numerous tracks found in the Belgian-blocked streets for old trolley tracks. However, since until a few years ago DUMBO was almost entirely given over to warehousing and manufacturing (except for the small Vinegar Hill neighborhood on the eastern end) trolley lines never troubled it north of Sands Street.

One clue that these were never trolley lines is that several pairs run on sidewalks and into buildings. These tracks belonged to the Jay Street Connecting Railroad, one of the shortest rail lines in Brooklyn. It was originally constructed (beginning in 1904) by the Arbuckle Brothers, who imported coffee from far-flung regions; it was unloaded from carfloats in the East River (not for nothing are there two streets in DUMBO called Dock and New Dock). Goods were shuttled into warehouses a lofts in the streets of DUMBO via the tracks. The JSCR ran its last load in 1959, and a good many of the tracks have remained in place since then.

Side note: I have decided to experiment with a change in the title card font, switching from the longtime Franklin Gothic Condensed to a more modern sanserif, Avenir. We’ll see if I like it, and if you like it. If not, I’ll go back to Franklin.

In early September 2020 I was not really ready yet to take the subway and brave whatever crowds there were into Brooklyn. I have since begun to do so cautiously, and in Manhattan and Brooklyn, the trains are sparsely populated. However, the #7 in Queens seems to be at or near pre-pandemic levels of ridership; this could be because few of its passengers drive cars or can afford cabs or online car services like Uber.

I did take the #7 to Hunters Point and take NYC Ferry to DUMBO as I was not yet ready to get the F in Manhattan and ride it to the York Street station. The ferry, operated by Hornblower Crusies, runs five routes plying the East River connecting stops in four boroughs (and future plans call for a stop in St. George, Staten Island). The fare is $2.75, same as subway and bus rides in September 2020, though the fare is heavily subsidized and there are no transfers to subway and bus routes. I suspect that the low fare is unsustainable and the rate will need to be raised sometime in the near future (with severe declinations in revenues, all public transportation is hurting during the pandemic).

I enjoyed the ride immensely, skipping from Hunters Point to Greenpoint to “North” and “South” Williamsburg to DUMBO. The weather was spectacular; there is indoor seating for when it isn’t. The ferry dock is at the north end of Old Fulton Street, near where the older Fulton Ferry landed up until 1924.

Before talking about what I found today let’s turn the clock back to 2017 when I found the Belgian blocks and JSCR tracks exactly where they had been for over a century along Plymouth Street south of Brooklyn Bridge Park. The amazingly detailed Open Street Map still shows the JSCR as dotted lines on DUMBO streets. As you can see the streetscape, tracks and all, was frequently used for commercial photo shoots because of their ambience.

In 1989, Bob Diamond, rediscoverer of the Atlantic Avenue LIRR tunnel, was hoping to revive streetcar service in several Brooklyn areas and gave a demonstration here on Plymouth Street with a classic trolley car he had acquired (it was pulled by a truck, but gave people an idea what it would be like).

If you’re a fan of the Belgian blocks and tracks, the news was not good in September 2020 as they had been pulled up and the street paved over. A look at Google Street View in July 2019 shows them still there (bear in mind that Google will update this view from time to time). You can tell from Street View that people enjoyed taking pictures here, as the streetscape was picturesque and relatively unique in NYC. The view overall is still the same but lacks punch without the blocks and tracks.

Proponents of paving over the tracks mentioned they’re tough on bicycles and motor vehicle axles and those considerations outweigh any ambience they may provide.

Left intact, however, was this recreation of the blocks and tracks at Plymouth and Washington Streets, as well as new flat brick pavement (with none of the older bricks’ unevenness) along Washington Street. By Brooklyn Bridge Park, aficionados will have to settle for this.

Ambience and atmosphere are not priorities of private and public developers. The “supertall” One Manhattan Square ruins the views of the north tower of the Manhattan Bridge from some angles, and more such towers are now in the planning stages. The glass tower replaced a low-rise Pathmark supermarket.

The news is a bit better on Plymouth Street on the two blocks between Pearl and Bridge Streets. There, the Belgian blocks and JSCR tracks have been left in place; however, I don’t know how long this will be the case. Here we are getting away from the Brooklyn Bridge Park area, so the DOT may be able to practice some leniency.

Two bridges: looking west on Plymouth Street under the Manhattan Bridge and toward the Brooklyn.

An unusual curb cut as the old JSCR tracks go into a building.

When I am in this part of Brooklyn I continue to press east past DUMBO into the remnants of a small neighborhood, some may even consider it a small town, named Vinegar Hill. There’s no longer a commercial strip, but Hudson Avenue, with weeds growing between its Belgian block pavement stones, can be considered the main north-south route.

When I first began doing FNY in 1998 one of my original shoots was in Vinegar Hill, an improbably isolated swatch of Brooklyn found by heading east on one of the DUMBO east-west streets all the way until there’s no further to go. The brick warehouses, powerhouses and light manufacturing that make up the eastern half of DUMBO (and indeed until about 6-8 years ago made up all of DUMBO before it was rezoned and went residential) give way, rather magically, to a Brigadoonish enclave of frame homes, long-disused storefronts, and on parts of Gold and Front Streets, some attached brownstones that appear as if they were airlifted in from Park Slope. In 1997, a small section was designated as a NYC Landmarked District.

Lording over all on the north is the massive Con Ed power plant, and on the east, the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

I explain a bit more about Vinegar Hill on this FNY page from 2009. The area doesn’t change much, but I did notice a couple of things. Whenever I enter, the place seems mostly deserted, with a few selected signs of life.

Hudson Avenue is a former commercial strip, as these photos of it between Plymouth and Front Streets from the 1940 Municipal Archives show. There were groceries, hardware stores, barber shops, and the usual things you would find in a commercial area in NYC. Most are gone now and only the glass picture windows remain as a reminder of that period. The buildings are completely residential now.

The avenue formerly extended continuously from the East River waterfront south to Fulton Street, and an elevated train, the old Brooklyn 5th Avenue El, once shadowed it between Myrtle and Flatbush Avenues. In the 1950s, much of it was eliminated by the construction of the Farragut Houses and the Brooklyn-Queens expressway’ today only the Vinegar Hill section remains, as well as a short block between DeKalb Avenue and Fulton Street.

Hudson Avenue looking north toward the East River. A large Con Edison electric power facility, the Farragut Substation, lines the East River shoreline between Jay Street and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and photography there is strictly verboten, but I am safely up the street and using the telephoto. You can see that a leftover Corvington castiron lamp is left over from mid-century.

Across the river in Manhattan is the Corlears Hook neighborhood, where the shoreline at the FDR Drive curves north. The brown building is home to the Sacred Heart Convent, the oldest all-girls’ school in NYC, founded in 1801. The street alongside it is Jackson Street, coincidentally…

…the former name of Hudson Avenue. Vinegar Hill was developed by Irish immigrant John Jackson in the 1840s. A proud Irishman, Jackson named his enclave Vinegar Hill after the June 1798 Battle of Vinegar Hill, an engagement in County Wexford, Ireland, during the Irish Rebellion of that year. (The rebels were defeated, and a massacre ensued — there would not be an Irish Free State until 1922).

Meanwhile, Water Street has since been renamed Evans Street, with the remainder of Water Street keeping its name west of Hudson Avenue.

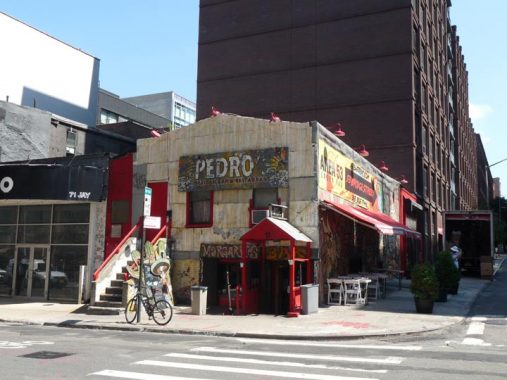

Vinegar Hill in the modern era was bereft of anywhere you could get something to eat other than a C-Town near the Farragut Houses on York Street, and Pedro’s at Front and Jay (see below). During the last decade, two restaurants have appeared, Vinegar Hill House and Cafe Gitane, next door to each other on Hudson Avenue at Water Street. Both are upscale and a bit pricey.

Harrison Alley is one of NYC’s rarities, a true dead end called an “alley,” on Evans Street. Its gate is kept locked and so I have never seen the house or two at the end of the shaded route.

There is this cryptic bit of information in Brownstoner from way back in 2006:

I went to a party at this house last fall. They had the alley done up with candles along both sides. The alley leads to a building that has been converted to an apartment by several artists. From what I heard at the party, the building was once the garage/stable for the Admiral’s Mansion which is literally right next door. From the vantage point of this picture, the mansion is on the other side of the fence on the left hand side.

Speaking of getting only a glimpse, the Navy Yard Commandant’s House (Quarters A), the home of all the Navy Yard’s commanders until the 1940s since its completion in 1807, can be glimpsed only through a fence when the gate is closed. There are better views of it on this FNY page which in turn links to a NY Times page in which the late great Christopher Gray got a look inside.

Meanwhile, here’s a new object on Evans and Little Street opposite the gate.

A Lot of Little: NYC’s “Little” Streets

Boorum & Pease manufactured and marketed office supplies, record-keeping supplies, and information storage and retrieval products, and was a leading manufacturer of blank books and loose-leaf binders. The company had an office and factory for many years in Vinegar Hill at Hudson Avenue and Front Street, and many Vinegar Hillers found employment here over the years. B&P, which had moved to Elizabeth, NJ, was acquired by Esselte Pendaflex in 1985.

More of the cold hard facts of life are coming to DUMBO, as a high rise apartment called Front & York is rising on what was formerly an empty lot for years along Jay Street between York and Front. This section of the neighborhood has no Landmarks protection. It’s 21 stories high and will contain 728 apartments.

Afraid I know little about one of my favorite buildings in DUMBO, #68 Jay at Front, a brick loft probably going back prior to 1900. There are two marvelous carven street signs on the ground floor. It faces two newer DUMBO objects.

Pedro’s, a Mexican restaurant at Front and Jay, predates most of DUMBO’s 21st Century development and was here long before 2002, when this NY Times article appeared.

You realize how much of the old neighborhood is still here at Pedro’s, mixed in among the Romanians and Panamanians and Frenchman and Minnesotans, and you listen to the entire world resting on the head of a beer: Milosevic, the rape of Romania, Islamic terrorists, rednecks, Protestants, the symbiosis of the Greeks and Albanians, Afro-Cuban rhythms, smoking causes birth defects, how to save a choking victim. And into the evening.

It seemed easier to beat sailors, a patron says to Mihai Hurezeanu, the barman.

”Yes, those were simpler times,” he said.

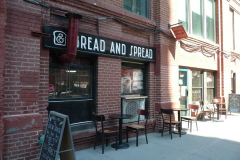

In just a few short years, eateries of all types have taken root in DUMBO, such as breakfast and lunch joint Bread & Spread, coffee house Beepublic (both in the 68 Jay building) and the DUMBO Market grocery and food court. There isn’t room (yet) for a supermarket, but a humongous Wegman’s has appeared in the former Navy Yard Officers’ Row at Navy Street and Flushing Avenue.

A look at the East River’s classic bridges (and the decidedly un-classic One Manhattan Square) on the line for the NYC Ferry back to Hunters Point.

I’ll take NYC Ferry again soon, while it’s still affordable.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

11/8/20

3 comments

Took my kids a few times this summer on NYC Ferry from Brooklyn Navy Yard to Rockaway and back. 2 40-minute boat rides for $2.75 apiece. Can’t beat that! 🙂

Kevin- Here’s some of 68 Jay St’s history, from a research product on old factory buildings I’ve completed:

Grand Union Tea Company

Built in 1915, by William Higginson. 10 floors.

The entire block bounded by Pearl, Jay, Water and Front Street consist of five separate structures, all built for the Grand Union Tea Company in stages between 1896 and 1915. This company was founded by Frank, Cyrus, and Charles Jones, brothers from Stamford, and conceived as a way to sell coffee and tea directly to their customers, rather than through independent grocers, as was the practice at the time. Initially selling products

door to door in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the Jones brothers established both the Grand Union and Jones Brothers Tea Company in 1872, pioneering the concept of chain grocery stores, a business strategy that cut

down their cost of purchasing goods. By the time their entire Brooklyn factory had been completed, almost 300 people worked on site, eventually growing to encompass 650 stores operated in almost every state in the

nation by the end of the 1920s. By 1917, this site, serving as factory and warehouse, was noted as being the largest of its kind in the nation, shipping 32.5 million pounds of coffee, 4 million pounds of tea, and 120,000

pounds of soap per year. Throughout the 1920s, most of their expansion was the result of purchasing large groups of groceries stores by rival companies. In 1928, Grand Union was purchased by a banking syndicate,

and these buildings were sold. While mainly physically similar to the neighboring 69-79 Pearl St., this building, constructed by the prolific concrete factory architect William Higginson, features several details that indicate

its later construction date, including groups of rectangular window blocks, rather than individual panes with arched frames. By the early 1920s, the building began housing smaller manufacturing tenants: one of the first

such companies was the regional retail grocery chain known as Globe Grocery Stores Inc., headed by Charles Hammack. In the 1930s, tenants included Delson Chemical Company, makers of canine medicine known asDelcreo Remedies advertised as curing asthma,rheumatism, vomiting, and distempter (a product unfortunately cited by the Federal Trade Commission as beingin effective in 1934), razor blade manufacturer Triangle Mechanical Laboratories Inc.- the 3rd-largest such company in the world in the late 1930s, and Goodman Products Corporation, a food distributor owned by Lillian and Hyman Goodman. In the 1940s and „50s, Plastina & Company, a garment firm owned by Benjamin and Rudolph Plastina, Interchangeable Brush Company, makers of mops, brushes and brooms formed in 1912, Gertsen Brothers, presumably a food distributor, and gas range maker J. Rose & Company were listed at this address. Additional late-20th Century tenants included P.M. Printing Company, in the 1970s. In the mid-1990s, the site underwent a residential conversion, with several ground- and upper-floor retail and gallery spaces.

Spent a lot of time in “Dumbo” as its now called as a kid back in the ’60s.It was such a peaceful ‘hood back then.The old warehouses just seemed to be resting finally after

so many years of toil,so quiet,only the occasional flapping wings of startled pigeons as you walked along the streets.Who remembers the licorice factory?Who remembers

that longshoremans diner under the bridge?How about “The Bank”?

Now that area looks like a shopping mall.In fact,all NY is starting to resemble a shopping mall.