BESET by nagging maladies and injuries…some of which are still ongoing (the lower back is a frequent target for the pain gods) …I was in the mood for a somewhat easier walk during the July 4th holiday weekend and remembered that I had not taken full advantage of NYC Ferry, which offers travel to several disparate neighborhoods in all five boroughs for the (heavily subsidized) cost of a subway ride, $2.75. Thus far, though, the service has seemed to attract wealthier business riders during the week and sun-trippers on the weekend; the problem lies in the riverside terminals, where few subway lines approach.

In future rides, I plan on riding between regions that present a contrast, such as say Corlears Hook and Governors Island, or East 90th Street and Soundview, Bronx (I had previously taken NYC Ferry there a few years ago). Today, I went from Hunters Point to Pier 11 Wall Street; the ferry makes stops at East 34th, Greenpoint (currently closed for repairs), North and South Williamsburg, DUMBO and Wall Street, which is the ferry hub as all lines end up there as the first or last stop (except for the West 39th to St. George line).

To begin, I walked from the Vernon-Jackson #7 subway to the ferry landing. This is the south end of Vernon Boulevard at Borden Avenue; you can see new residential towers going up in Greenpoint in the background. In the 1970s or 80s, when I first bicycled from Bay Ridge to Hunters Point using the Pulaski Bridge, it was possible to walk across these unelectrified Long Island Rail Road tracks to a Vernon Boulevard stub on the other side. Until the 1950s this intersection was shadowed by a ramp taking Vernon Boulevard traffic over the Vernon Boulevard Bridge, which connected it with Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint. When it was demolished, the Pulaski Bridge connecting 11th Street in Queens with McGuinness Boulevard in Greenpoint replaced it.

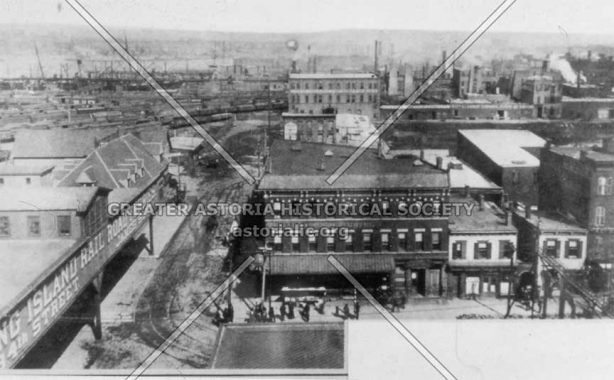

Dominie’s Hoek (Hook), originally the western end of the town of Newtown, was originally settled when a tract of land was awarded to Everard Bogardus, a Dutch Reformed minister (dominie), in 1643. The land was later owned by British sea captain George Hunter and by 1825 had become known as Hunter’s Point. It began the transition from rural farmland in the 1860s when the Long Island Rail Road built a terminal that would be its primary connection with Manhattan until the East River tunnels and Pennsylvania Station were built in 1910.

Today the LIRR Long Island City stop is mostly orphaned, as Penn Station reduced its importance. At one time it was very heavily used to get to Manhattan, as Nassau and Suffolk County riders were dropped off here and ferried across the river. Today, just a few trains depart and arrive in the weekday mornings and evenings, with none on the weekends. However, during the week this and the tracks going to the Hunters Point Avenue stop make it a prime area for train spotting as the Newtown Pentacle demonstrates. Passenger trains departing from here use main line tracks through Woodside and Jamaica, though that wasn’t always the case as some employed “Montauk branch” tracks through mid-Queens that are now strictly for freight.

I spotted a rare signage mistake, as some of the station signs are in all caps and Helvetica Regular instead of Bold. Upper and lower case is the usual rule.

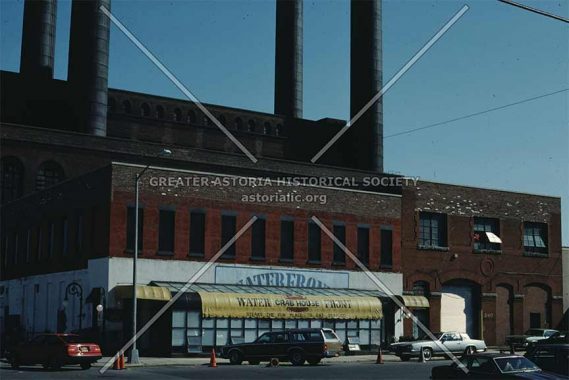

In the shadow of the former LIRR Powerhouse, on Borden Avenue and 2nd Street in Long Island City across the street from new residential towers, you will find what used to be the Waterfront Crabhouse, located in a two-story brick building. Its present blandish exterior reveals no clue of its former role as Tony Miller’s Hotel, a social epicenter of Long Island City.

Miller constructed a lavish, three-story hotel here in 1881, described as containing a huge horseshoe-shaped bar formed from a single piece of black walnut; three dining rooms; and 30 bedrooms on the third floor. It was quickly able to attract a sizable and star-studded clientele that included architect Stanford White (who co-designed the massive powerhouse a block north), auto racer Barney Oldfield, boxer Tim Sullivan, and entertainer Lillian Russell. Teddy Roosevelt was seen at Miller’s, and Grover Cleveland was spotted drinking at the bar. The hotel and restaurant’s eminence derived directly from its location across the street from the former Long Island City terminal of the Long Island Rail Road. Prior to 1910, when Penn Station was opened, Long Island City was as far west as the railroad got in Queens.

The hotel lost momentum after Tony Miller’s death in 1897 and the LIRR Manhattan connection was instituted in 1910. In 1919, Prohibition dealt the final blow and the hotel was shut down. The building subsequently served as a phonograph factory, a warehouse, and went through other stints as a restaurant and a hotel for several decades. A 1975 fire claimed the third floor. Restaurateur Anthony Mazzarella opened the Waterfront Crabhouse in 1978, and it attracted famous visitors just as Tony Miller’s did in the old days: Bobby Hull, Paul Newman, Ed Asner and Maureen O’Hara, and many other sports and entertainment luminaries, have all visited over the years.

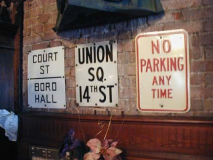

Mazzarella, a boxing fan and promoter, surrounded the bar with boxing memorabilia as well as subway signs, board games, advertisements, bottles, framed pictures, and other donated artifacts. One wall was full of sheet music; another with photographs of what the Crabhouse was like in the golden age of Tony Miller. Sadly, after Tony Mazzarella’s recent death, his family decided not to continue running the Crabhouse. The building in 2022 was hosting the Kuei Luck Early Childhood Center.

Around the time of my birthday each August, I would round up some friends for a Sunday afternoon fun fest at the Crabhouse. I would hope that the family has all the artifacts in storage; sadly, I don’t know what happened to the two Bishop Crook lamps at the front door.

For those unfamiliar with the Hunters Point waterfront, it has transmogrified incredibly in just the last few years. It was once a place where goods from East River float barges were unloaded and reloaded onto railroad cars, which proceeded to the main LIRR tracks and shipped to interior Long Island. There was also plenty of warehousing and manufacturing along the waterfront. When all that left the area in the 1960s, the waterfront area was abandoned and became a wilderness that remained in place as recently as the mid-2010s.

About a decade ago, high rise apartment buildings began to sprout and a new street layout was built along the waterfront, along with a new school building and library. The Penn Station Powerhouse’s smokestacks were removed and the building converted to residential. As far as the public is concerned, the most beneficial aspect has been the new Hunters Point South Waterfront, which has a soccer field, playgrounds and prime views of much of the east coast of Manhattan.

It was time for a ferryboat ride. The boat cut directly across the East River to 34th Street, the terminal of a long-ago ferry (see 1800s photo of the Miller Hotel above). Just as in Hunters Point, supertall residential buildings dominate the region surrounding it such as the K-shaped American Copper Building towers, one of which has an unusual angled design that makes them look from across the East River in Hunters Point as a giant reverse letter K or perhaps a crooked letter H. The two towers are residential, despite their industrial sounding name, and are connected by a pedestrian skybridge. The two buildings do have copper cladding, with both open for occupation in 2018.

The ferry headed back east across the river to Brooklyn for a few stops and then on to Wall Street. On the way to Wall Street, I sat on the top deck in the sun and was able to get photos of the Williamsburg, Brooklyn (not shown) and Manhattan Bridges. Like I’ve been saying, I should really do this more often.

Can a building look angry? I have always thought the Continental Center, originally built for an insurance company at South Street and Maiden Lane, looks like it’s in a mood, with an impenetrable glassy face and sharp angles you could cut yourself on. The octagonally shaped building opened in 1983, the same year as the South Street Seaport.

I headed west along Maiden Lane, which the story goes was named in the Dutch era in the 1600s for women washing clothes in a stream that now runs in the sewer system.

I like the symmetrical look of Wall Street Plaza, whose address is officially #88 Pine Street but also fronts on Front Street and Maiden Lane. I’m not around here often and I thought it was a new building, but it’s almost 50 years old as it was completed in 1973.

Across Maiden Lane from Wall Street plaza is #160 Front, the oldest building in the immediate area (some sources say 1917), which was once an office building of some type but is now residences. StreetEasy has a look at one of the apartments.

Fletcher Street is a generally unremarked-on narrow alleyway that has had numerous building projects springing up alongside it in recent years. Nonetheless, it has been permitted to retain its Belgian block paving. The street is named for Benjamin Fletcher, a British NY governor from 1692-1698 who awarded printing contracts to William Bradford and installed the guns at Fort George at the Battery. He also awarded Trinity Church funds to construct its first church through the sale of drift whales…whales that had washed up on the shore (Bones, blubber etc. could be put to good use).

Bradford’s tombstone in the Trinity Church graveyard reads:

Here lies the body of Mr. William Bradford,

Printer, who departed this life May 23, 1752,

aged 92 Years. He was born in Leicester in

Old England in 1660 and came over

to America in 1682, before the city of

Philadelphia was laid out. He was printer

to this government for upwards of 50 years

and being quite worn out with old age and

labour he left this mortal State in the

lively Hopes of a better Immortality.

Reader, reflect how soon you’ll quit this stage,

You’ll find but few attain to such an age;

Life’s full of pain; lo, here’s a place to rest;

Prepare to meet your God, then you are blest.

Here also lies the body of Elizabeth,

wife to the said William Bradford, who departed

this life July 8, 1731, aged 68 years.

Not to be outdone by the obscure Fletcher Street, Front Street also has kept its paving blocks.

Who says Tribeca has all the castiron front buildings? Here’s one at #90-94 Maiden Lane at Gold Street, a commercial building completed in 1871. The building’s facade was commissioned by Roosevelt & Son, a leading plate glass and mirror importer. Theodore Roosevelt Sr., father of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, was one of the company’s principals.

Sculptor Louise Nevelson resided at #222 East 7th Street, which received a bottom to top makeover some years ago. Nevelson’s 1978 installation, Shadows and Flags, can be found at Louise Nevelson Plaza, Maiden Lane and Liberty and William Streets in the Financial District.

#135 John Street is perhaps most famed for the digital clock designed by graphic designer and instructor Rudy de Harak (1924-2002). It was installed in 1971 as part of the building next door, 200 Water Street. The clock is 45×50′ tall and consists of 72 illuminated squares, the top row numbered 1 to 12 and the bottom squares numbered 00 to 59. When it worked the clock displayed the correct hour (the squares on top) minute and second, with the numbers flashing on every second from 00 through 59. When I passed it on July 3rd, it was showing the correct time, 1:52 PM.

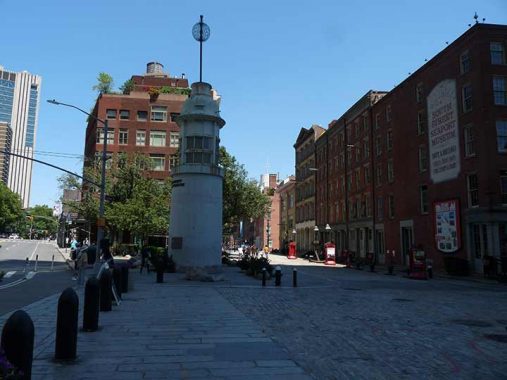

New York City has formal, informal and completely accidental homages to those who died in the sinking of the HMS Titanic on April 15, 1912. On the corner of Fulton and Water Streets stands a reminder of one of the world’s most infamous naval disasters. The Titanic Memorial Lighthouse was dedicated exactly one year after the sinking and was originally placed atop the Seamen’s Church Institute, a 14-story building at South Street and Coenties Slip downtown. In 1967 the Seamen’s Institute moved and the building was later demolished; the lighthouse, fortunately, was preserved and by 1976, had been installed at its present location. The tall pole at the apex originally had a metal ball that, when signalled by a telegraph at the National Observatory in Washington, DC, would drop at noon daily. Unfortunately the memorial has not been tended to in recent decades, and a group has been founded to reverse the deterioration.

This block of Water Street was on the waterfront during the colonial era, until landfill extended Manhattan island further east and Front Street was constructed, and later further east and South Street was built.

The Landmarks Preservation report for these three Water Street buildings surprisingly keeps architectural jargon to a minimum:

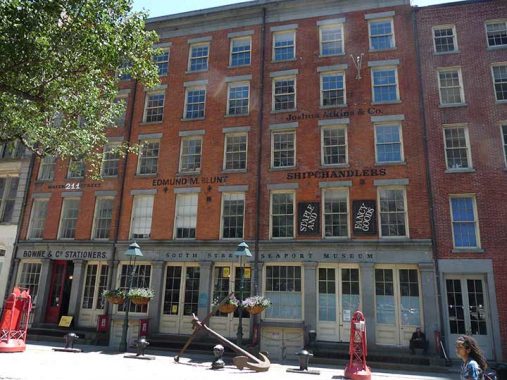

These three Greek Revival warehouses were erected as a group in 1835-36, for three individuals, P.J. Hart, Gabriel Havens and David Louderback. Louderback, a mason by profession, probably constructed his own building and may also have built the other two. The buildings, among the finest in the Historic District, are excel lent examples of the widely popular commercial adaptation of the Greek Revival style . This treatment of the stores helps to unify the facades. Granite, a popular Massachusetts building material, was commonly used for New York City storefronts … At Nos. 207 and 211, the fine, tall double entrance doors are flanked by a large display window to the left and by paneled wood doors, leading to an open-riser staircase, to the right. Originally hoistways were located at the interior, in front of these stair cases. At No. 211, the original slip sill has been retained at the large window and the early granite rain trough remains hare and at No. 209. A paneled wood door at No. 211 leads to the basement of the building. Nos. 207 and 211 have been handsomely restored by the South Street Seaport Museum; No. 207 is now the Museum Model Shop and No. 211 houses Bowne & Co. Stationers.

Bowne & Co. Stationers at 211 Water Street is a working job print shop as well as a department of the South Street Seaport Museum. It was one of the first preservation projects undertaken by the Museum in 1975.

Two hundred years before, a dry goods store called Bowne & Company had opened, and it later focused on printing, especially financial documents like prospectuses and merger proxies. One of its customers was Lehman Brothers, the investment bank that collapsed in 2008. Today, Bowne Printers still works in handset type, as was done 200 years ago. The Bowne family has far flung holdings in the NHYC area; the John Bowne House, built in 1661, still stands in Flushing, Queens. Other Bownes settled in City Island, a spit of land in Eastchester Bay, and there, Bowne Street recollects their presence.

The museum says the original shop’s inventory was itemized in a city directory in 1829 as gilt-edge letter paper, straw paper, tissue paper, copying paper, drawing paper, blank books, bill books, cargo books, bankbooks and seamen’s journals.

Print shops of this type originated common phrases like “uppercase” and “lowercase” as the letters were once kept in 2 separate cases. “Mind your p’s and q’s” came about because the two lowercase letters are mirror images of the other. “Leading,” the space between lines of type, was once determined by inserting leaden slugs.

Lo and behold I actually came by on a day when the stationers was open, and I was able to come in and gawk at the printing presses, which are periodically demonstrated by store personnel.

#213-215 Water Street came along thirty years after its neighbors, in 1868. The Italianate building was originally built for A.A. Thompson & Co., a tin and metals concern.

#8 Spruce Street, formerly the tallest residential building in NYC, since surpassed. It’s now known as New York By Gehry, after its architect, Frank Gehry; it’s his first major building in NYC after many years. The tower contains only rental units (898 in total), something of a rarity in New York’s Financial District. It contains a public elementary school, which the Department of Education owns, and is made of reinforced concrete. It is 76 stories and 870 feet high.

I like the building, even though many Forgotten NY fans don’t seem to like anything built later than 1950. I say that in jest, not in anger. I do like that Manhattan is dynamic, but so many of the new towers going up in places that never had them before like Hudson Yards and Hunter’s Point are plain glass boxes. #8 Spruce is new and different.

In one of the great travesties of the modern era, Pier 17, which catered to people with moderate incomes, was demolished in 2018 and a much more ambitious substitute with expensive restaurants and a rooftop arena took its place. As part of the demolition derby, the 1907 Tin Building, where so many Fulton Fish Market transactions took place, was razed and this note for note reconstruction took its place.

From wikipedia, which I turn to for quickie descriptions; forgive me…

Wavertree is currently the largest large iron sailing vessel afloat. The ship was built in Southampton, England in 1885 and was one of the last large sailing ships built of wrought iron. She was built for the Liverpool company R.W. Leyland & Company, and is named after the Wavertree district of that city.

The ship was first used to carry jute between eastern India and Scotland. When less than two years old the ship entered the “tramp trades”, taking cargoes anywhere in the world. In 1910, after sailing for a quarter century, the ship was dis-masted off Cape Horn and barely made it to the Falkland Islands. Rather than re-rigging the ship its owners sold it for use as a floating warehouse at Punta Arenas, Chile. Wavertree was converted into a sand barge at Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1947 and acquired by the South Street Seaport Museum in 1968.

In recognition of Wavertree‘s symbolism of New York’s History, the Seaport Museum was awarded a 13-million dollar, city-funded grant for her unprecedented restoration in 2015. This provided the necessary means for her restoration including the completion of her masts, yards, and rigging, the installation of her ‘tweendeck, and the refitting of her iron-hull. [Seaport Museum]

I got a number of photos from the Seaport but in the interest of brevity I’ll direct you to my last major exploration of the area in 2019.

I returned to the NYC Ferry back to Hunters Point. I’d really enjoy a ferry to Little Neck or Douglaston, but placing a landing at the northern end of Little Neck Parkway would entail a lot of construction that would no doubt be vetoed by local politicians as it’s a primarily residential area. But the LIRR station is nearby and would make a perfect rail to boat transfer. (I don’t know if Udall’s Cove has the depth to carry heavy boats.)

Back in Hunter’s Point, here’s St. Mary’s Church. Built in 1887 by pre-eminent church architect Patrick Keeley, St. Mary’s, with its distinctive clock steeple, was the tallest structure in Hunters Point, other than the demolished powerhouse smokestacks, for over a century until the Queens West development of the 1990s. The church is built from brick and brownstone in a simple Gothic design, featuring multiple pointed arches across the façade on Vernon Boulevard, and a tall steeple that rises several stories. Clad in gray slate, the steeple houses clocks on each side, and marks the skyline as it rises over Vernon Boulevard.

As Forgotten Fans know I’m a fan of subway mosaics and signage. In 1915, subway designer Squire Vickers went all out with the Vernon-Jackson station, inlaying multicolored tiles. A close look reveals that they were hand cut and hand laid. Remember, there were no calculators in 1915, so rulers and slide rulers were used for measurements and calculations.

Vernon Avenue? Before 1920, Queens streets today called Boulevards had other names, mainly just plain “Avenue.” It was around that time that today’s Queens street and house numbering began in earnest.

13 comments

Until you get north of Leeds pond, the cove has less than 10ft of water

Some years back I was at a store (Banana Republic?) on Pier 17 looking at pants. They were “artfully” displayed on a table in a way that made it impossible to see the size labels without moving them. So I was indeed moving them to see if they had my size when an employees came up to me and not very politely asked me to please stop messing up the displays. I said something rather rude to him and walked out of the store.

Re your Browne family comment “…City Island, a spit of land in Eastchester Bay”. City Island is just what it’s name says it is: an island. A spit is a coastal deposition feature, basically an elongated sand bar attached at one end to the coast, extending out from the coast and unattached at the other end. Please do not denigrate that unique community lest you arouse the wrath of the clam digger.

Hey, I love City Island and I’m there at least one per year. My low carb diet will keep me out of Johnny’s Famous for the moment though.

Another taxpayer-funded scam for the benefit of the well-connected:

https://nypost.com/2022/07/08/eric-adams-should-stop-paying-for-deblasios-nyc-ferries/

A $12 per-ride subsidy isn’t too terrible … Shore Line East is $55.

The ferry CF continues even though it’s time to abandon ship:

https://nypost.com/2022/07/17/eric-adams-plan-to-save-nyc-ferry-doesnt-go-far-enough/

I never saw what was wrong with the building that already existed for Pier 17. This could have been NYC’s version of the Quincy Market in Boston where they still keep the building despite what stores are in it, but that wasn’t the case. The new version looks like nothing more than a bland, glass mall that I can find almost anywhere. Also, the stores in it I hear are more expensive in it than what was there originally. Then again, I haven’t been to Pier 17 in a bit over a decade, but that’s partly because I haven’t been the neighborhood lately.

The Wavertree was demasted and turned into a barge?So all those masts and rigging

in the picture above is all just a bunch of fake,jive-ass crap?

I added a further comment.

I know Roosevelt & Son as its current incarnation, Roosevelt & Cross, which morphed into being a financial services firm by the early 1900s.

https://www.roosevelt-cross.com/about/#history-details

Continental Center, aka 180 Maiden Lane, was where I worked for Nomura Securities for ten years until 1998 when it decamped to the World Financial Center.

In regards to de Harak’s digital clock: the number panels are all squares in the 6 by 12 grid. So, the clock can’t be 45×50 tall (as also in the blogspot article). A Google Earth measurement gave me ~48 feet wide, so the height, based on that, is 24 feet. The panels are 4 feet square. Call it 25 by 50 allowing for 2” between panels.