In October I took advantage of the preternaturally balmy and clear weather (Central Park recorded .01″ of rain the entire month) and walked through Chelsea and The West Village, catching up on things I hadn’t checked out for awhile. When I got to 6th Avenue and West Houston, I noticed something I hadn’t picked up on all the time I’ve been walking the streets down there.

At 6th Avenue, West Houston gains two eastbound lanes and roars off toward the FDR Drive, passing Katz’s Deli and other highlights. I last walked Houston from end to end in 2005 so I really should do so again.Non-New Yorkers note: here the street is pronounced HOUSE-ton.

Westbound motorists have a choice to make at 6th Avenue: choose the lane that continues on West Houston toward the Hudson River, or the one that gets you onto Bedford Street northwest into the heart of the West Village. Both streets are one-way westbound.

However: motorists going north on 6th Avenue can turn left on Bedford Street. At least, that’s what the street sign says. It’s not quite true, though you will indeed wind up on Bedford when you turn left.

I noticed that there are still four West Houston Street addresses on the north side of the street: #172, 174, 176, 178, even though Open Street Map and the Department of Transportation mark them as on Bedford Street.

If you look carefully, you can see the addresses marked on the buildings.

So, what’s going on?

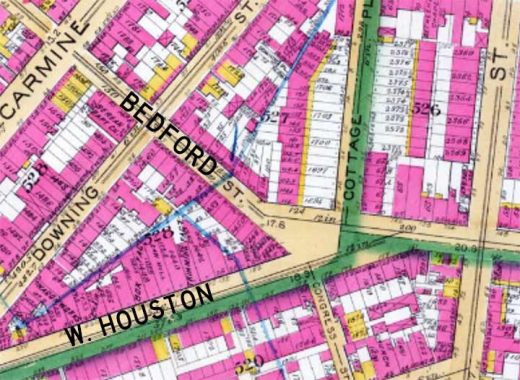

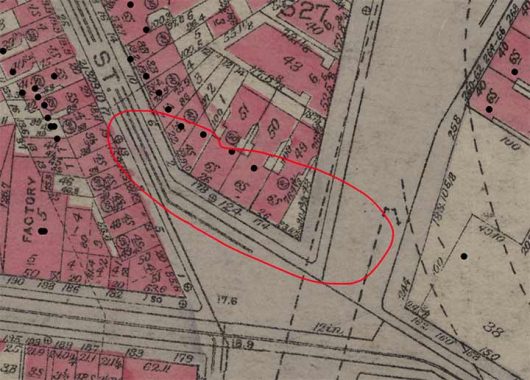

Things are a bit clearer on the 1905 map upon which I marked West Houston and Bedford Streets. Before 6th Avenue was extended south as a right of way for the new IND Subway which urned east on Houston in the 1920s, West Houston and Bedford met at a wide plaza bisected by the now-vanished Cottage Place and Congress Street. Bedford Street began with addresses #1 and #2 west of the plaza.

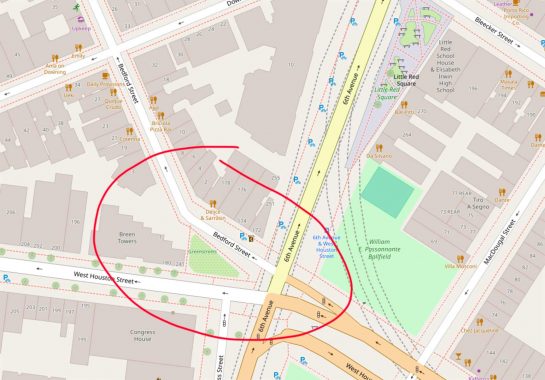

I have circled the addresses in red on this 1920s map. You can see that 172 (not yet built), 174 and 176 West Houston continue west of the new 6th Avenue, with odd numbered West Houston Street addresses on the south side.

The break from West Houston to Bedford was formerly clearer. There was a bishop crook lamp with signs for both streets at the real intersection of West Houston and Bedford.

So what happened to the wide plaza? It’s still there. But years ago, a green, gated mini-park, which so far has evaded getting an official name, was plunked on top of it, sundering west Houston and Bedford Streets. The walk within is called Gilda Radner Way, named for Gilda Radner (1946-1989) a charter member in 1975 of the original Not-Ready-For-Prime-Time Players, the first and arguably best comedy team from Saturday Night Live; her characters, still fondly remembered today, included Emily Littella, who hilariously misunderstood news reports, and anchorlady Roseann Rosannadanna (based on real-life 1970s WABC news anchor Roseanne Scamardella).

Six years after Ms. Radner’s death from ovarian cancer, an organization named in her memory, Gilda’s Club, now known as Red Door Community, was set up as a support group for those living with cancer and their friends and loved ones. The NYC branch can be found at 195 West Houston Street.

Thus… even though mapmakers and the Department of Transportation consider all of the street shown here to be Bedford Street, in the foreground it’s still the north “fork” of West Houston, and Bedford Street doesn’t begin until the bend in the road, where you will find #2 and #3 Bedford opposite each other across Bedford Street.

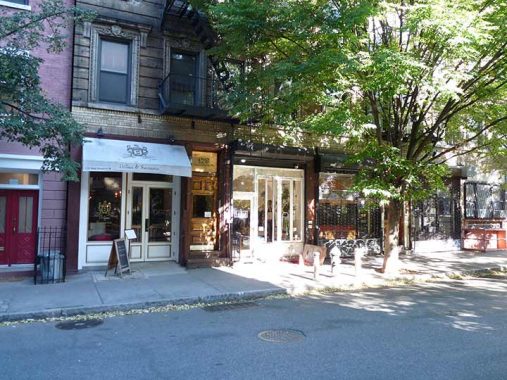

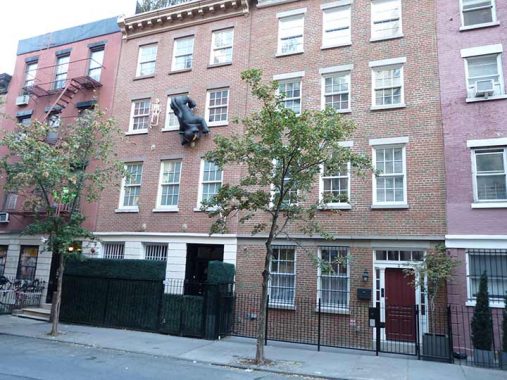

In this photo, #2 Bedford (left) and #178 West Houston (right) stand beside each other.

Is that the end of the story? Not quite. In the 1950s and 1960s, there was a plan to bruit through a new street between Houston and Bedford, Verrazano Street, which would connect 6th Avenue and 7th Avenue South as part of the also never-built Lower Manhattan Expressway plan; but community opposition thwarted the proposal.

The 4-story Federal-style brick dwellings on the east side of Beford west of 6th Avenue were constructed from 1828-1830, shortly after the street opened. Most were originally three stories and had a 4th floor added in the 1870s.

Apartments from the early 1900s at Bedford and Downing Street. Some years ago, Bedford Street received a set of retro Type F lampposts from the Department of Transportation.

This 5-story walkup was constructed in 1888. The restaurant on the ground floor, breakfast-lunch-brunch Daily Provisions, was preceded by Ditch Plains, named for Ditch Plains Beach in the Hamptons.

Village Tavern, Bedford at Leroy, opened in 1998 and the building it’s in, as a garage in 1937.

When 7AS was built, it crossed Bedford Street between Leroy and Morton, creating two traffic triangles too small to build anything on. The city maintains them as Greenspaces, but both are fenced with the one at Bedford and Morton has a sign saying “WFMV 2006.” The 2006 is likely the date of construction while there are no radio stations with the letters WFMV anywhere in the NYC vicinity.

The Bedford-Leroy triangle has no cryptic mark. I should mention here that Leroy Street is rather unusual because west of 7AS it takes a southwestern bend, and the portion between the bend and Hudson Street is called St. Luke’s Place, but only on the north side! All this is explored on an FNY page from 2012.

The west side of Bedford between Morton and Commerce Street features a number of Federal style brick attached buildings dating to the late 1830s. I really should have investigated that carriage up ahead and gotten a batter photo.

Beat writer William Burroughs (1914-1997) lived at #69 Bedford in the mid-1940s, around the time this tax photo was taken. His most famed works were likely “Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict” (1953) and “Naked Lunch” (1959).

70 Bedford, south of Commerce Street, was given its own historical plaque in 1966; as it says, it was constructed in 1807 by sailmaker and court officer John P. Roome.

In a house so narrow it seems to rate only half an address, is 75-1/2 Bedford Street, a house only 9-1/2 feet wide. There used to be stables inside the block adjacent to the Isaacs-Hendricks House (see below), and the narrow building was constructed in 1873 on what used to be the carriageway entrance. Famed poet Edna St. Vincent Millay lived in the building briefly in 1923-24.

The Isaacs-Hendricks House, #77 Bedford Street at the southeast corner of Commerce, is one of a handful of remaining buildings on Manhattan built in the 18th Century. It just got in under the wire since it was built in 1799.

Large sections of it including the brick facing were added to the house in 1836, and the third floor is practically “new”, since it was added in 1928. It is a former farmhouse owned by Harmon Hendricks, a copper merchant who supplied Robert Fulton with materials for copper boilers that powered the historic Clermont steamboat run in 1807.

#85-87 Bedford Street at Barrow Street. Originally called Reason Street was named for Thomas Paine’s pamphlet “The Age Of Reason” and Paine lived in the area for a time. Occasionally, the name was corrupted to “Raisin Street.” Because of the Raisin Street mispronunciation, it was decided to rename it in favor of artist Thomas Barrow.

The handsome brick apartment buildings went up in 1889.

The most townhouse at #86 Bedford was once one of NYC’s most pipular hangouts for authors and other artistic types. Chumley’s is probably the only major bar or restaurant in New York City that has never had a sign or marking of any sort on its exterior to mark its presence. Yet most Greenwich Villagers knew where it was and most nights, it was packed. Chumley’s building dates to the 1830s and was originally a blacksmithery. According to legend, in the pre-Civil War era it was a stop where escaped slaves could find a haven (there was a Black community on nearby Gay Street). At length it became a gathering place for leftist radicals. By 1922, developer Leland Chumley had established a speakeasy/gambling den in the old building.

During and after Prohibition Chumley’s became one of NYC’s many literary hangouts. The difference here is that the authors’ original dust jackets, and their portraits, line the walls of the place on all sides. You will find just about every big name in 20th Century literature here from Hemingway to Mailer to Ginsburg on the wall.

And mine, as well. The ForgottenBook cover was framed and hung during book party for Forgotten NY The Book in September 2006. Take a look at some of the festivities on this page. Unfortunately, soon after this, a wall collapsed and Chumley’s was closed for the 9 years it took to do repairs; after briefly reopening under new management, Chumley’s announced they would close permanently in July 2020, unable to recover from the Covid lockdown. I’d love to get my framed book cover back, but I don’t know where to start.

Most didn’t even enter Chumley’s via #86 Bedford; rather, it was accessed via a small passageway leading from Barrow Street called Pamela Court.

According to legend the term “86 it” for “kill it” or “forget about it” comes from a warning the cops would give, phoning ahead to Chumley to let him know they were on the way and customers should “86” or book out the entrance/exit.

#17 Grove Street, at the corner of Bedford, was built in 1822 by window sash maker William Hyde, and is one of Manhattan’s few remaining wood-frame houses. It looks terrific in the snow during Christmas season.

Across Bedford Street at Grove is PS 3, occupying part of the block between Hudson, Bedford, Grove and Christopher Streets is so large it had to be built to accommodate the curve in Grove Street. The school has been here for a long time — the Marquis de Lafayette visited PS 3 during his triumphal tour of the United States in 1824, as the plaque facing Hudson Street attests.

A 1917 “time capsule” created by school alumni was opened in 2009:

The copper box had a couple of medals that were given to alumni and to graduating students, as well as programs from a few annual [former principal] B.D.L. Southerland Association dinners. School songs and engravings of the long-bearded Southerland were among the contents, along with a roster of distinguished old graduates.

The historical outline chronicles the school from 1818 when it opened with 51 pupils in a building on Trinity Parish property acquired by the Free School Society. It grew to 200 students, and in 1820 the Free School Society built a new building, which served boys and girls. In 1860, a new brick and stone structure replaced the previous building.

In the early days, Grammar School 3 was famous for its special “sand system” writing program, consisting of a 15-foot-long wooden box 6 inches wide with the bottom stained black and covered with a thin coat of sand. Students would practice their penmanship writing in the sand –uncovering the black bottom — with a wood stylus as thick as a goose quill. It was such a remarkable device that General Lafayette came to inspect it in 1824, according to the historical sketch. [The Villager]

It’s hard to get a photo of #102 Bedford, because of the tree in the foreground and I was here when the building was in shadows. #102 is an 1830 townhouse was renovated beyond remembering in 1925 by Clifford Daily with help from financier Otto Kahn. Daily, an amateur architect, considered the surrounding buildings mundane and wanted to liven things up. But Kahn took over the building and offered Daily $5000 to clear out. Daily reluctantly agreed, but vowed to someday return. The story goes that he plunged two bottles of champagne in wet cement in the basement and said he would break them out when he returned to Twin Peaks. The bottles are still waiting.

To its right is #100 Bedford, also constructed in the 1830s by window sash maker William Hyde (see above)

The back end of PS 3, a massive public school building designed by schools architect C.B.J. Snyder in 1905, can be seen on Bedford between Grove and Christopher. In 1971, the school became the John Melser Charrette School (named for a charrette, a a meeting in which all stakeholders in a project attempt to resolve conflicts and map solutions).

#107-117 Bedford, just south of Christopher,

[were] built for [saloonkeeper] George Harrison. The first three houses of the row, Nos. 113-117, were built in 1843; the others followed the next year. These residences remained in the Harrison family until 1877 and, as they have been altered very little, they still retain their mid-Nineteenth Century appearance today. {Greenwich Village Landmarks Report]

Lucille Lortel, known as the Queen of Off Broadway, could also be called the Queen of the 20th Century; she was born in 1900, and died in 1999. The old Theatre de Lys, in a building constructed in the 1860s, was acquired by Miss Lortel in 1955 — independently wealthy, she brought works by American playwrights such as McNally and Albee and Europeans Genet, Ionesco and many others to prominence for the first time in the USA. The de Lys was renamed for Lucille Lortel in 1981. There is a mini-walk of fame outside the theatre featuring famed playwrights.

The offering at the Lortel, Chstopher Street and Bedford, in October 2024 was Kenneth Lonergan’s play “Hold On To Me Darling” with Adam Driver.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

11/24/24

3 comments

The font used on The Village Tavern signage is reminiscent of that used throughout The Village, wherein Patrick McGoohan was incarcerated in “The Prisoner.” I’ll bet that’s not a coincidence.

“And so to Bedford…”

Greetings, my Pepys…

Chumley’s is one of the most tragic Covid losses. It managed to reopen after so many years, only to be kiboshed for good after a few years.