FOR centuries, the constructed circle in Salisbury Plain that is Stonehenge has puzzled the public on its meaning and purpose. The culture that built it more than 5,000 years ago disappeared into history, leaving us with few clues. Looking at the cityscape from above, what questions would future generations ask about the Rego Park crescents and traffic circles of the five boroughs? One such example is Glen Oaks Oval in eastern Queens, where an oval-shaped park is ringed by an octagonal set of streets around it and linear townhouse co-ops, in total 110 acres containing 2,904 units in 134 buildings.

At the turn of the 20th century, Glen Oaks was part of Deepdale, the property of William K. Vanderbilt II, whose holdings straddled the city line, with his home on the Nassau side in the Village of Lake Success. A portion of the estate was developed as the Lake Success Golf Club, and on the Queens side, another golf course where the North Shore Towers stand, with the rest of the land purchased by the Gross-Morton Company for a housing development. It sought to address the housing shortage for World War Two veterans and their families.

Concerning oval-shaped parks, Williamsbridge Oval in the Bronx is a former reservoir, but Glen Oaks Oval does not have a transformative past. It was built on an undeveloped plain in 1948. The park contains three baseball diamonds, a playground, and an adult exercise area.

The only artistic element in this park are two sculptures of dogs guarding the playground. One had its face chopped off by vandals and looking underneath, their anatomy reveals that they are female.

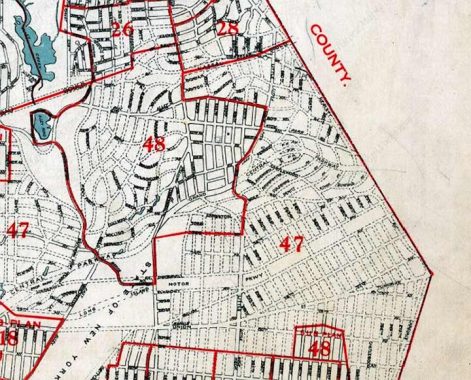

A map of the area from 1928 shows dotted lines for planned streets here, envisioning an alphabetical sequence of Ainsworth, Bridgewater, Coleridge, Dewitt, and Ethan, with the route of Vanderbilt’s Long Island Motor Parkway as a linear park, as seen on this 1937 map. After the private highway’s abandonment, only the section west of Winchester Boulevard became parkland, and the 3-acre parcel that became Glen Oaks Oval.

The only name from this map that was realized is Bridgewater Avenue, which runs for two blocks on a ridge north of the co-op. Instead of the parallel alphabetical avenues, Gross-Morton created a circular plan whose streets and avenues conformed to the borough-wide numbered grid. The curves slow down vehicles, and going east across the city line, that’s why many suburbs have a maze-like layout, to prevent through traffic.

Architect Benjamin Braunstein designed the residences and shopping strip on Union Turnpike in a Georgian revival design that spoke of the past. The sizable lawns offered open space, urban living in a suburban setting. Braunstein’s extensive portfolio in Queens also includes Electchester, Mitchell Gardens and Linden Hill in Flushing, Mowbray Apartments in Kew Gardens. The Flushing resident built freestanding apartments, co-op complexes, and garden apartments on superblocks.

Signs announcing Glen Oaks Village appear on all roads entering this complex, giving the sense of it as a village inside the city but unlike Sea Gate, Fieldston, or Forest Hills Gardens, anyone can drive and park on these streets. The city is filled with neighborhoods that have “village” in their names, such as East, West, and Greenwich villages in Manhattan, Heartland Village and Village Greens on Staten Island, and Middle Village in Queens, all named for the small-town feel where neighbors know each other by name.

Looking at an aerial survey of the recently-completed Glen Oaks from 1954, the last farm on the scene was operated by Creedmoor psychiatric center, later becoming the Queens County Farm Museum. In the foreground is the Glen Oaks golf course, which is the highest point in Queens, and Hillside Hospital that was later absorbed into LIJ Hospital. The forested parcel between the farm and Grand Central Parkway is Iris Hill, which contains a home for developmentally disabled individuals run by the state-funded nonprofit ANIBIC.

The mansion was built in 1930 as the residence for the executive director of the Creedmoor State Hospital. As the mental hospital reduced its footprint, its holdings east of Cross Island Parkway were developed as a public school campus and the farm museum. The hilltop house overlooking these two sites is still owned by the state, leased by ANIBIC as a seniors residence.

The exact names of the neighborhoods here is unclear. Atop the highest point, North Shore Towers has its address as Floral Park; LIJ Hospital is in New Hyde Park; and Queens County Farm Museum is in Bellerose. The zip code map has Little Neck Parkway separating Bellerose from Floral Park and Glen Oaks. The latter two share the 11004 zip code. A New York Times map of the area from its 2012 report on Glen Oaks gives Iris Hill, the farm, and neighboring public school complex to Glen Oaks.

Most residents consider Union Turnpike as the border between Glen Oaks and Floral Park. The Queens Public Library branch at Glen Oaks is on the Floral Park side of this road, serving both neighborhoods. Completed in 2011, its award-winning design is inspired by sustainability and fitting in with its low-rise neighbors by having a sizable basement for its shelves. The word “search” appears on its glass facade with an interior artistic element by Janet Zweig.

Looking at the official city map, zip codes with a 113 prefix have their main post office in Flushing, 114 is in Jamaica, corresponding to the towns that were annexed into New York City in 1898. The borderline curiosity here is the 110 prefix for Floral Park and New Hyde Park, which corresponds to communities in western Nassau County. Floral Park is a neighborhood in Queens and a village in Nassau County. Residents of Floral Park and New Hyde Park in Queens have their post offices across the city line in Nassau.

Whether or not Glen Oaks is within Floral Park or a separate neighborhood, as a co-op on a set of grid-defying superblocks, it has a strong sense of identity, centered at the oval, which residents use as a circular jogging path and the little league has its home field.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

8/19/25