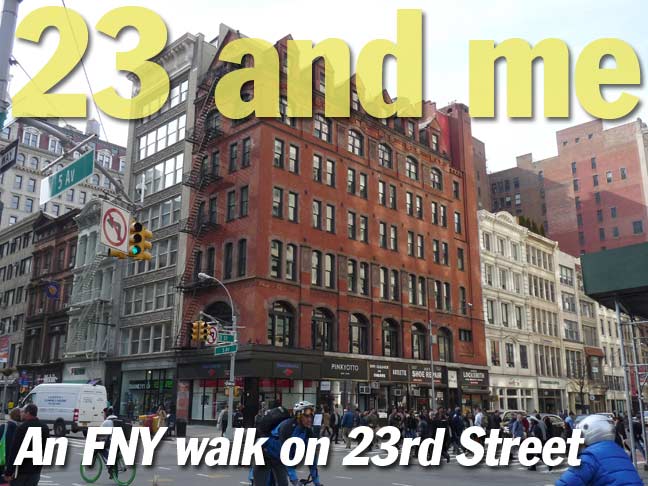

In early February I was tired of the routine and desired a rove. It occurred to me I hadn’t had one of my favorite treats lately, one of the burritos prepared by Press on East 23rd Street, which I discovered while on a temp assignment in 2013 at Tiffany & Co., which has its offices on 5th and 23rd Street. I enjoyed the place so much, I profiled it in FNY in 2014. Unfortunately like all good things it went out of business, but in a rare lick of good fortune, the place that replaced it at 34 East 23rd, Benvenuto’s, retained the “press machine” and the wraps and burritos made at Press have survived the transition, so I was satisfied after all.

To work off lunch I made a short trip east on 23rd, up 2nd, then back west to Penn Station and have enough for an FNY page that will be by no means comprehensive, but hopefully, satisfying like the ground beef, tomato, lettuce and pico burrito I had at Press, er, Benvenuto.

Shadows are harsh in February and light is limited so bear with me on this page. After exiting the train at 7th and 23rd I checked on the Muhlenberg Library just west of 7th. The Library went up in 1906 and was designed by the firm Carrère and Hastings, which built the main branch at 5th and 42nd Streets (1912) as well as Staten Island’s Borough Hall (1907). It was among NYC’s first Carnegie libraries, built with funds donated by Scottish-American industrialist/philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

The name honors William Augustus Muhlenberg, the first rector of the former Episcopalian Church of the Holy Communion at 6th Avenue and West 20th Street a few blocks away. That building, designed by Richard Upjohn and built in 1846, is no longer a church; it served as the home of the Limelight disco for several years and now hosts a discount outlet, Limelight Marketplace, as well as a Grimaldi’s Pizza shop. I worked next door on West 20th for a few months in 2011-2012.

As an aside, when I worked at Tiffany & Co. at 200 5th and West 23rd Street from 2013-2014, I noticed that several of the steel columns on the floor I worked on were marked “Carnegie.” Two great industries on one building, Tiffany jewelry and Carnegie steel.

Seen today on West 23rd just off 7th Avenue, 167 and 169 are nothing to write home to Mother about, though they do show hints of past glory, with Ionic pilasters (half-columns) on 167.

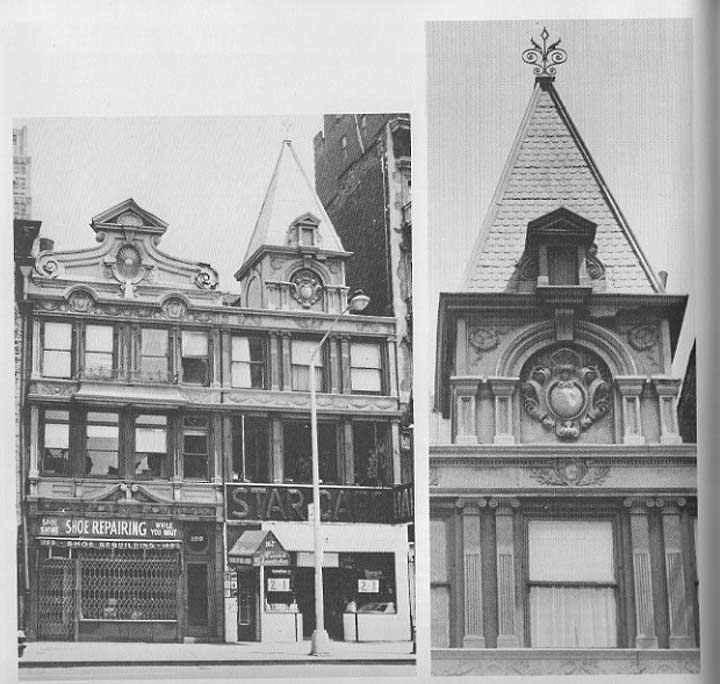

Marvel, though, at this shot from the early 1970s that appears in Cast-Iron Architecture in New York, an invaluable 1975 book by Margot Gayle and Edmund V. Gillon Jr. Sadly, neither building was landmarked because their elaborate roof treatments have been lopped off! I remember the conical roof of #167 still in place when I worked in the area in the 1980s and 1990s.

West 23rd was once NYC’s theater district. Both buildings were erected in 1898 and reflect the then-new Beaux Arts esthetic. The roof cornices were made of sheet metal. Apparently by the 1990s both cornices were deemed unsafe and, rather than shore them up, they were removed.

This 6-story brick building on West 23rd boasts a brown brick and terra cotta finish, with the words “Traffic Building” over the second floor. Note the interesting detail like the pair of eagles below the triangular roofline, the twisting pilasters, and foliate designs next to the nameplate, all the work of architect and designer Abraham Fisher.

The name is associated with automobiles only tangentially. When it was constructed, it housed a branch of the Traffic Cafeteria Corporation, no doubt patronized by truckers, deliverymen, etc. After several years of union and mob trouble, the cafeteria moved out around 1940.

An eatery once again occupies the ground floor.

The St. Vincent de Paul Roman Catholic parish was founded in Manhattan in 1841. In the aftermath of the French Revolution in the 1790s, the Church underwent a period of re-evangelization to restart the teachings of the Catholic faith in that nation, and noticing this, Catholic bishops in the USA invited some French missionaries to this country to spread Catholicism in what was still largely a frontier country. In the 1830s there was, as yet, no French-speaking Catholic Church in NYC and French missionaries who came here conducted services with the indulgences of French Huguenot churches, and also in St. Peter’s Church downtown on Barclay Street.

The Church of St. Vincent de Paul, named for a canonized 16th-17th Century French missionary and charity worker, was first established on Broadway and Canal Street. The church moved into this building on West 23rd, designed by Henry Engelbert, in 1858. Not only was it the first French-speaking Catholic church in NYC, it was also the first parish church to allow black and white worshippers to take Communion together. The church was redesigned to its present appearance, with four Corinthian pilasters, in 1939.

Sadly St. Vincent’s closed its doors in 2013 and suffered damaged from a bombing in 2016. Its future disposition is not yet known.

Toward 6th Avenue you pass a building that features a collection of mosaic and terra cotta letter K’s. This is the former Ehrich Brothers Ladies Mile store, constructed in 1889, and currently home to a Burlington Coat Factory on the ground floor. But there’s a secret about this building — the K’s — that most passersby fail to notice.

“Ehrich” doesn’t begin with K, so why all the K’s? This dates to the era when the building was owned by Chicago merchants J.L. Kesner Company, who hired architects Taylor and Levi to add all the letter K’s, which remind me both of the subway signage being designed by Heins and LaFarge at the time and also looking forward to the Machine Age mosaic lettering that came about in the late 1920s.

Of course the building still has its original EB initials, in a much less obvious place, on the pilasters near the roofline.

The interior of the Grand Lodge Headquarters for the Freemasons at 6th and West 23rd must be seen to be believed. Over 60 different Masonic lodges meet here in 12 riotously woodworked and decorated rooms, each of which has a pipe organ. The building seen here actually contains offices, the rents of which support the actual Lodge building which fronts on West 24th Street.

The Masons are a fraternal society tracing their history back to a stonemasons’ guild in medieval England, with a history of doing philanthropic and community work; they have counted George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Ludwig van Beethoven, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Clark Gable, Harry Houdini, and Count Basie among their membership. Tours are available Monday through Saturday and on Sunday for groups.

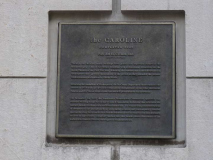

After what seemed like decades as a parking lot, the SW corner of 6th Avenue and West 23rd Street finally sprouted this mixed-use building, called The Caroline, in 2002. As the plaque explains, many buildings have previously graced the corner, including the Booth Theatre during the Civil War (explaining the bust of Shakespeare; his plays, produced and acted in by Edwin Booth, the brother of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, were presented there). The McCreery department store replaced the theater building and survived into the 20th Century.

61 West 23rd Street is a cast-iron front building found way uptown from Tribeca, where most such buildings can be seen. Originally Horner’s Furniture Store, it was constructed in 1887 and designed by architect John B. Snook. Note the many large, wide windows. Sunshine was a premium for product showrooms in an era before electric lamps and while gaslight could be expensive.

43 West 23rd Street, the Castro Building, constructed in 1903 [Henry J. Hardenbergh, arch.], was originally the George C. Flint Furniture Showroom, then a warehouse, then administrative offices for the Girl Scouts and then Touro College’s Graduate School of Education and Psychology, and a Castro Furniture showroom. It is currently the flagship sales location for Spectrum (formerly Time Warner Cable). Judging by the cat friezes on the decorative medallions, you could also call it the “Cat-stro Building.”

The former Stern’s Department Store, a large building painted wedding cake white on #40 West 23rd,is a current huge Home Depot outlet where I am found occasionally looking for lightbulbs. Stern’s Dry Goods was founded in 1867 by brothers Isaac, Louis and Benjamin Stern, the sons of German Jewish immigrants. After two locations in the area that would be called Chelsea, Stern’s built this voluminous building at #40 on 1892 [William Schickel, arch.] It was a part of the Ladies’ Mile district and offered expensive fashions, but also affordable clothing and goods for middle-class shoppers. Stern’s tenure here was short-lived however: the store moved further uptown to 5th Avenue near West 42nd Street in 1913. The store was finally merged with Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s in 2001. The “SB” monogram can still be seen over the building’s central arch.

West 23rd between 5th and 6th Avenues looks very much like the way it must have looked when this row of buildings was constructed around 1865, give or take a few years, except for the storefronts. The building on the left was home to banker Benjamin Nathan, a former VP of the New York Stock Exchange and president of the Shearith Israel synagogue, whose murder was never solved; next door, #14, was the birthplace of novelist Edith Wharton (The Age of Innocence, The House of Mirth)

Another Henry Hardenburgh design, the former Western Union headquarters on the SW corner of #186 5th Avenue and West 23rd was built 1883 in a Queen Anne style. In the height of technology in those days, workers here sent messages via pneumatic tube two and a half miles to the downtown office on Broad Street that has since been demolished. Note “W.U. 1883” near the peak on the 5th Avenue side, and the Western Union entablature on the 23rd Street side, which seems to be depicting the four winds of legend. You could probably cut your finger on the six dormers on the 23rd Street side. Hardenburgh went on to design the Plaza Hotel 36 blocks uptown.

I’m a big fan of the two remaining classic Twin lampposts at the confluence of 5th Avenue, Broadway and West 23rd Street. They’re two different models: the Type 24 Twin, and a hybrid post that is a combination of a Type 1 Twin and a Type 3 Bishop Crook. I never get tired of taking their pictures and writing about them…as I did along with other 5th Avenue Twins on this page in 2011.

From 2013-2014 I worked at 200 5th Avenue for Tiffany & Co. Originally, 200 5th was called the Fifth Avenue Building (its elevators still were showing the FAB initials on their interiors before they were replaced after 2003). Through much of its history the building was home to the International Toy Center and since 2011 it has hosted the offices of Hecla Iron Works of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, named for an Icelandic volcano, built the clock, as well as many of the long-gone subway exit and entrance kiosks (the last of them disappeared in 1967).

This gilded, ornate street clock is perhaps the most magnificent still existing in New York City. It was installed in 1909, at the same time 200 5th was built. Tiffany & Co. which sponsored the restoration the clock in 2003 by the Electric Time Company.

The Flatiron Building, in the wedge formed by Broadway and 5th Avenue, is hardly “forgotten” so I won’t dwell on it very long. I will say it was originally the Fuller Building when completed in 1902 as Chicago architect Daniel Burnham’s only major NYC work (his disciple Frank Lloyd Wright has only two of his designs in NYC).

Due to the geography of the site, with Broadway on one side, Fifth Avenue on the other, and the open expanse of Madison Square and the park in front of it, the wind currents around the building could be treacherous. Wind from the north would split around the building, downdrafts from above and updrafts from the vaulted area under the street would combine to make the wind unpredictable. This is said to have given rise to the phrase “23 skidoo“, from what policemen would shout at men who tried to get glimpses of women’s dresses being blown up by the winds swirling around the building due to the strong downdrafts. wikipedia

The Flatiron Cowcatcher

The Skiddoo Twins

Sharp-eyed observers will note that Broadway actually widens between East 22nd and 23rd. In the past decade, though, traffic engineers have seen to it that only one one-way lane is open to automobile traffic, with the remainder converted to bike lanes and sitting areas in the warm months.

Broadway widens here because the eastern leg of the widening used to be the Eastern Post Road, a colonial-era road that reached to upper Manhattan. When the grid street system surveyed by John Randel from 1807-1811 was built here in the 1830s, the Post Road became less important and disappeared except for angled building lots in the ensuing decades. Madison Square Park originated in 1844 and wiped out its southernmost leg. Surviving uptown portions include st. Nicholas Avenue.

Senator William Henry Seward‘s (1801-1872) main claim to fame is that he engineered the sale of Alaska from Russia to the U.S. in 1867. But he was also a powerful government figure: governor of New York, 1838-1843, U.S. Senator from New York, 1849-1861, and Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson’s Secretary of State, 1861-1869. At the 1860 Republican Convention he nearly beat out Lincoln for the nomination. Though antislavery, he opposed war with the Confederacy.

Seward was attacked by John Wilkes Booth the same evening that Booth assassinated Lincoln. (Booth’s brother, Edwin, a famous actor of his time, is memorialized with a statue in Gramercy Park, a few blocks away.)

This Madison Square statue, by Randolph Rogers, was unveiled in 1876. When Rogers completed a statue of Lincoln for Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, there were striking similarities between the two figures, and some claimed that to save money he used the same figure twice. What happened is that the committee for the Seward statue was unable to afford the sculptor’s full fee. So with a few changes in body details, some repositioning of limbs, and the alteration of the Emancipation Proclamation to fit the size of the Alaska Purchase agreement, including the signature pen, Rogers was able to recycle the statue. Seward was the first New Yorker honored with a public monument.

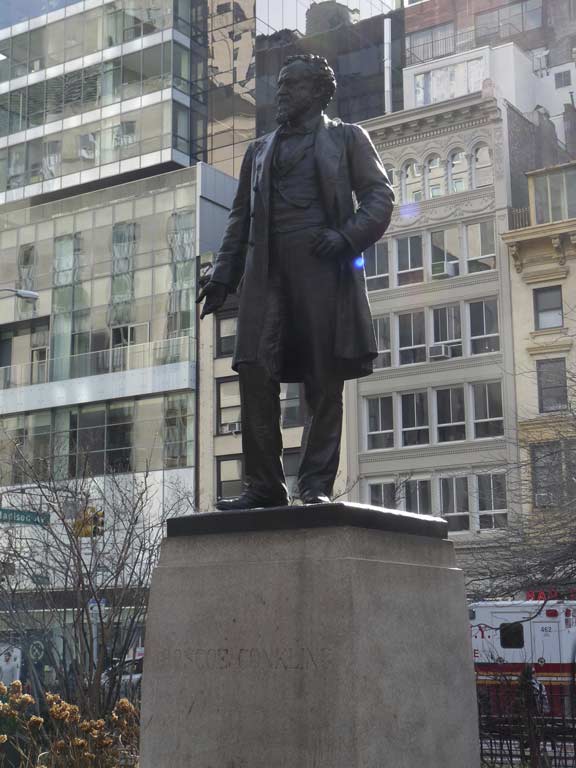

Another “forgotten” politician whose statue can be seen from East 23rd is Senator Roscoe Conkling. Described as a forceful, charismatic and flamboyant orator, Conkling was Senator of New York between 1867-1881 after two stints at the House. In 1876, Conkling lost in a squeaker to Rutherford B. Hayes for the Republican presidential nomination (Hayes later triumphed in the general election by amassing more electoral, though not more popular, votes than Democratic opponent Samuel Tilden, in a situation not unlike the 2000 and 2016 presidential elections.) In March 1888 Conkling was caught outdoors near Madison Square at the worst of the Blizzard of ’88 and died from exposure 6 weeks later.

1920’s comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle was named for the senator. Apparently, Arbuckle’s father thought his son was the product of an affair, so he named him after a hated politician of his youth…Senator Roscoe Conkling!

Sculptor John Q.A. Ward’s memorial statue was dedicated in 1893. Ward has many statues scattered about Manhattan including the George Washington at Federal Hall on Wall Street.

A few feet away from Conkling is the illuminated Star of Hope, a 5-pointed star on a 35-foot high pole was erected in 1916 to commemorate the country’s first community Christmas tree that was lit in Madison Square in 1912 “as a gift to the less fortunate in the city.” The annual tradition lives on with festivities sponsored by the 23rd Street Association and the Department of Parks.

Originated by restaurateur Danny Meyer in July 2004 Shake Shack is a popular permanent stand that serves hamburgers, hot dogs, shakes and other similar food, as well as wine. Its distinctive building was designed by Sculpture in the Environment, an architectural and environmental design firm based in Lower Manhattan. It has since become a chain with several locations around town and has expanded nationwide and into a number of international cities in the near and far east.

Madison Square, for the past several years, has hosted a series of contemporary art pieces. In February 2017 Martin Puryear’s “Big Bling” was the featured item and remained until April 2.

The largest temporary outdoor sculpture Puryear has created, Big Bling is part animal form, part abstract sculpture, and part intellectual meditation. The artist’s signature organic vocabulary appears in a graceful, sinewy outline and an amoeboid form in the work’s center. The piece “will command Madison Square Park in New York like a kind of Trojan horse,” writes Hilarie M. Sheets in the October 1, 2015 issue of The New York Times.

Big Bling’s architectural language suggests a building that is accessible by ascension through its levels. Its storeys are obstructed by chain-link fence, a barrier to entry, which covers all visible surfaces of the sculpture. In contrast to the coarse materials employed throughout most of the work, the gold shackle is a shimmering beacon that simultaneously adorns and restrains. (The term “bling” is rooted in urban youth and rap culture of the 1990s and refers to flashy jewelry and accessories.) [Madison Square Park]

Western Union Building from Madison Square Park. This was a 62-degree day on February 8th. The following day NYC received 10 inches of snow.

When I got my first job in 1981 it was near Madison Square, and Cajun seafood restaurant/bar Live Bait was here at #14 East 23rd across from the park then and it’s still there now. (I remember little else from the era, except that friends worked nearby and we went to the Old Town Bar, which I appreciated for its ice cold air conditioning; the New York Rocker offices were a few doors away on 5th Avenue. I have worked in the area again since and Eisenberg’s and again, Press were my lunch options of choice.) Not a fan of Schnipper’s across the street. It’s OK, but I’ve had better.

Continuing east on East 23rd to Park Avenue South, the 8-story brick and terra cotta building on the SE corner has always been a favorite for a couple of reasons. Look up to the 7th floor and you will see terra cotta renderings of children, their arms outspread as if in supplication. These aren’t cherubs, which are usually naked and winged.

The representations are there because of a little girl named Mary Ellen McCormack, who in 1874 lived on West 41st Street in Hell’s Kitchen with her adoptive mother. Her father had died in the Civil War and her mother could not afford to care for her and sent her to the city orphanage on Blackwells, now Roosevelt Island. She was adopted by a couple named Thomas and Mary McCormack. Thomas died soon after the adoption, and the elder Mary severely abused and beat Mary Ellen, using whips and scissors on her. Alert neighbors complained to the then-Department of Public Charities and Correction who put an investigator, Etta Angell Wheeler, on the case.

Wheeler was shocked to discover that there was no specific city agency that handled the cases of abused children. She then approached the Association for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals — the ASPCA(!) to see what they could do about Mary Ellen. ASPCA founder Henry Bergh hired a prominent lawyer, Elbridge Gerry, a grandson of Elbridge T. Gerry, James Madison’s Vice President and the initiation of the term “gerrymandering,” to argue Mary Ellen’s case before the NYS Supreme Court. After heart wrenching testimony by Mary Ellen — despite the abuse, she was an insightful, intelligent girl — Mary Connolly (she had remarried) was found guilty of assault and battery. Mary Ellen wound up adopted by Etta Wheeler and her mother and sister, and moved to upstate New York. She married and had six children, adopting an orphan herself. She had a content life and died at age 92.

Bergh and Gerry helped found the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, which is still active today. 295 Park Avenue South was constructed in 1892 as offices for the SPCC. The children on the 7th floor were modeled after those designed by Andrea Della Robbia at the Ospedale degli Innocenti, “Hospital of the Innocents” in Florence, Italy, which opened in 1445.

295 Park Avenue South also preserves the street’s old name, 4th Avenue. Long ago, Park Avenue was called 4th Avenue all the way north to the Harlem River, but after railyards for Grand Central Terminal were built on it after 1874, city fathers kept monkeying with the name; wishing to de-emphasize its association with belching railyard smoke, 4th Avenue was renamed Park Avenue above East 32nd and later, Park Avenue South from Union Square to East 32nd. Today, 4th Avenue only runs from Cooper to Union Squares atop the Post Road’s old path and is the shortest of Manhattan’s numbered avenues by a long shot.

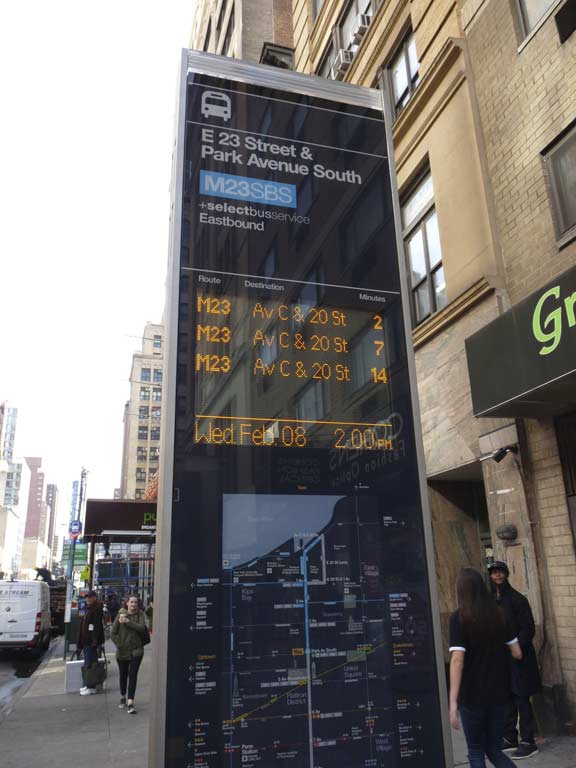

These new bus stop signs have been introduced at selected routes in Manhattan and Queens. You can see how long you have to wait until the next bus comes.

The “MHT” is a former logo for Manufacturers Hanover Trust, a bank my mother worked for for many years, and where I opened an account in 1984. After a series of mergers I won’t bore you by detailing here, MHT is now JP Morgan Chase. Mets broadcaster Ralph Kiner was fond of calling them “Manufacturers Handover.”

Illfelder Importing was on East 23rd between 1938 and 1969; according to the Indispensable Walter Grutchfield, they have a long and complicated history that goes back to 1860s Bavaria.

The Art Moderne Gramercy Theatre, named for nearby Gramercy Park, is an Art Moderne building constructed in 1937 [Charles Sandblom, arch.] It closed as a first-run movie theater in 1992, reopened in 1995 as a “Bollywood” theater presenting movies made in India, became an Off-Broadway theater in 1999, and a concert venue since 2006.

The site of Baruch College, on Lexington and East 23rd, has its beginnings in 1849 when the Free Academy, a boys’ secondary school, was opened here in a building designed by James Renwick, Jr. City College occupied the site by 1903 and its business school was established in 1919. The current campus building was constructed in 1928-1929. The City College business school was named the Baruch School of Business in 1953 and in 1961, 1968, Baruch College, after CCNY graduate and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch, an 1889 graduate.

One of the oldest bars in NYC is hidden in plain sight on the south side of East 23rd near 3rd Avenue: The Grand Saloon, now known as The Globe.

I’m nothing without my sources…

Jim Naureckas, New York Songlines:

This building dates to 1843; in 1880 it was the St Blaize Hotel & Restaurant, a celebrated brothel frequented by Diamond Jim Brady. In 1911 it became Klube’s Steak House; that name is still visible on the copper facade. It was a speakeasy during Prohibition.

Walter Grutchfield, 14 to 42:

The original Mr. Carl August Klube had worked in Germany as a waiter before he came to America and bought what would become Klube’s in 1911. In 1908, he married Agnes Klinger, who had also been born in Germany. Agnes’ brothers Henry and Joe had butcher shops on Third Avenue.

Klube’s was a restaurant and bar. It was actually originally called Klube & Klinger’s, which is, frankly, a mouthful. Since the Klube family owned it during Prohibition, it’s a pretty safe bet that they ran it as a speakeasy in the 1920s. In its day, it was known as the Little Luchow’s—a reference to the more famous German restaurant.

The family apparently did pretty well by the place. Old man Klube wore three-piece suits, a diamond stick pin and a pinky ring. His wife was an avid shopper with a driver and a personal maid. The couple had one son, Carl Henry Klube, who eventually assumed control of the place and ran it into the 1960s. Victor Borge was a regular guest. A 1950 Times account has a man named Hans Nitzsche as having been Klube’s chef for decades. The third-generation Klube worked there for a short time, but soon after it was sold.

I have some photos from this set on Lexington Avenue and East 29th, but I’ll put those in the kitty for use later.

“Comment…as you see fit.”

4/9/17

16 comments

This has put me in the mood for a trip to NYC.

Nice article. Even though it’s now long gone, 1989, I’m surprised you didn’t mention Madison Hardware. It was at 105 East 23rd St and despite being called a “hardware” store, it was the premier Lionel Train store in NYC. I only walked past it once, in 1983, the guys I was with had no Lionel interest so I didn’t get to go in and check it out. Here’s a NY Times article from when it was still open: http://www.nytimes.com/1984/12/12/garden/treasure-laden-hangouts-for-hobbyists.html?pagewanted=all

Excellence, as usual.

Thanks.

Thank you for all the information of my neighborhood!

One minor correction…the Baruch School of City College became Baruch College in 1968, not 1961. That was the same year that Hunter College in the Bronx became Lehman College, all part of changes in the City University of New York.

I was present at the Lehman College dedication ceremony in 1968. I had a good summer job at Hunter Bronx/lLehman & as I was removing weeds from the campus plaza while many “important people” droned on & on. The summer crew was composed of Hunter College employee offspring (my mother worked at Hunter 68th St in Buildings & Grounds, for instance). Patronage is disgusting, except when it works for you.

What some didn’t know about the Flatiron Building is that it was one of the first skyscrapers in NYC built outside the Financial District, though the hopes of creating a new business area around it at the time didn’t work, despite that working with 1 Times Square, which was built a few years later.

Power hungry power broker Roscoe Conkling had an interesting relationship with fellow stalwart and POTUS Chester Arthur who himself has a statue at the opposite end of Madison Park.

Wasn’t Gilbert Hall?American Flyer across the street from Lionel?I seem to recall that 200 Fith Av was the “”TOY””show room of NYC before 1960….I also seem to recall a H&H near both Lionel and Gilbert Hall/American Flyer????used to the place to go after the Macys Parade to stock up on catalogs so you could let “”Santa”” know what you wanted to ad to your trains..Thanks for the walk down the lane Thomas Wolfe said you couldn’t go back to!!!

I lived my babbling infancy near one end of West 23rd Street, in the spanking-new London Terrace complex; and my Mom lived out most of her later years near the East end, in Stuyvesant Town. Thanks again, Kevin, for another terrific tour!

28 West 23rd Street housed the Universal Camera Corp. from 1938 to 1952. It began with a line of small plastic cameras that used their proprietary film load and then expanded into a multitude of different models including roll film and 35mm still cameras and 8mm video cameras and projectors. During the war Universal made binoculars for the armed forces and an interesting gadget called an Icaroscope that allowed the viewer to look into the Sun for enemy aircraft without getting blinded. Probably their most famous product was the half-frame, rotary focal plane shutter Mercury I and II 35mm camera. After the war the company ran into difficulties with quality control and questionable business practices and it moved out in 1952, finally fading into oblivion by 1964.

Your reference to the Old Town bar reminded me of a sign it had in its windows in the 1980s when the huge restaurant America was open a few doors down from it on East 18th Street. “This is Ellis Island,” it said. “Come here before you go to America.”

Actually, Ralph Kiner also called Manufacturers Hanover “Manufacturers Hangover.”

Jayson Stark of the Philadelphia Inquirer/ESPN used to have a Sunday column in the Inquirer on baseball that included a portion called “Kinerisms of the Week” where readers sent in things they heard from Kiner on Mets games (as in the 1980’s and ’90s, Mets games that aired on Channel 9 actually aired nationally as WWOR was actually a superstation).

Lewis Powell, not John Wilkes Booth, made the assassination attempt on William Seward.

Great stuff! I learned a lot. One question – I was surprised that Live Bait was open in 1981. I could have sworn there was an Irish bar (that served thick cut sandwiches during lunchtime to the area workers nearby — insurance guys and others ) in place of Live Bait in 1985. I thought it was called McShandons or something like that and that Live Bait opened a year or so later….Am I imagining it?

Love seeing your pictures but I am desperately looking for a picture of the old F.W.Woolworth store that was located on the south west corner of East 23rd and Park Ave. South.