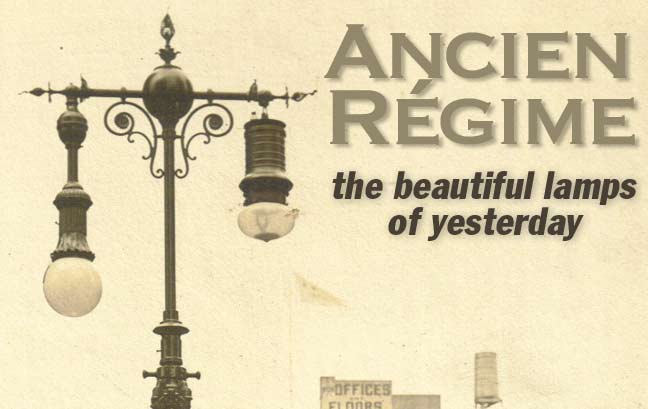

Streetlamps powered by electricity first appeared on New York City streets in 1892, and while from about (as far as your webmaster can tell) the 1930s on, they fell into four basic genres, the long-masted “Corvingtons“, twinlampsused on main streets and boulevards, bishop crooks, and the reverse-scrolled Type Fs. In the wild and woolly early days of electric streetlighting, though, myriads of styles appeared from competing companies, rivalling each other in their ornate ironwork. The bishop at left, for example, has scrollwork I haven’t seen anywhere else.

Streetlamps powered by electricity first appeared on New York City streets in 1892, and while from about (as far as your webmaster can tell) the 1930s on, they fell into four basic genres, the long-masted “Corvingtons“, twinlampsused on main streets and boulevards, bishop crooks, and the reverse-scrolled Type Fs. In the wild and woolly early days of electric streetlighting, though, myriads of styles appeared from competing companies, rivalling each other in their ornate ironwork. The bishop at left, for example, has scrollwork I haven’t seen anywhere else.

In 1892, seven competing gaslighting companies served the city: Consolidated (later Con Ed), Equitable, Standard, New York Mutual, Central, Northern and Yonkers…and this was when New York City consisted of Manhattan Island and parts of the Bronx. There were six electric lighting companies as well: Brush Electric Illuminating, United States Illuminating Company, Thomson-Houston Electric Lighting, Mount Morris Electric Lighting, Harlem Lighting, and North River Electric Light and Power. As of 1892 the city had 27,083 gaslamps,1,199 electric lights and 140 naphtha lights. Edison Electric Illuminating was in business as well, housed since its beginnings in 1880 in a 5-story brick building at the vanished corner of Pearl and Elm Streets, as well as six generating stations uptown.

After consolidation in 1898, many competing companies continued to produce street lighting, and there were a lot of different post designs. A catalog prepared by the Bureau of Gas and Electricity in 1934, The System Electric Companies: Photographs of Street Lighting Equipment as of November 1, 1934, described the surviving designs that year, and there were dozens and dozens. Some were variations on the general twinlamp, bishop crook, Corvington and reverse scroll designs we still see in New York, or are being reproduced in retro versions…but others are flights of fancy that haven’t been seen since…

It’s hard to believe now that a lamppost of this type, shown above, would be at all practical; just check the acorn-style luminaire dangling by a thin wire, photo left. Described by the booklet as Type 8 “Avenue A” it was photographed on Park Place downtown, left, and at Lenox Avenue and East 124th Street, right. Most of these had disappeared by the 30s, but a clutch of them survived on Park Place and Murray Street in Tribeca into the 1940s. In the photo at right, note the IRT kiosk at the 125th Street station. Photo left, Andreas Feininger, from New York in the Forties

Type 24 with “6-foot special arm.” A lone sample was photographed on Washington Street in “Pre-Beca” in 1978 by Forgotten Fan Bob Mulero (an indefatigable lamppost chronicler for years). As decades went by, elements of one style post were often combined with others, which is what happened here: the shaft and mast have been attached to a “Type 6 BC” base that most often was seen on bishop crook posts. Also, a 1940s Westinghouse luminaire was attached to the mast via a device most often seen on Type 24 “Corvington” long-armed posts. This was a fascinating preservation in 1978, as all of this style’s fellows had long-disappeared by then. In the few years after the World Trade Center was built between 1970-74, the region formerly home to the old Washington Produce Market lay barren for several years, and otherwise defunct lamppost styles were preserved as well.

Since we’re now in an age when every concievable corner of Manhattan is being developed for staggeringly-priced domiciles and offices, it’s mind-bending to consider that several square blocks were empty like this for years, but that’s precisely what happened. In 1975 the apartment complex Independence Plaza was constructed between Chambers, Hubert, Greenwich and West Streets, the neighborhood became known as Tribeca, and this scene was obliterated…as was the de facto lamppost museum.

First Castiron

The first castiron post to appear on NYC streets was what The System Electric Companiesclassified as the Type 3 Fifth Avenue post, in 1892. At first, only one corner per intersection got one, but later on, this was expanded to two. The posts went through a variety of luminaires at first, some quite fanciful, until the style shown above were settled on. These later received “acorn,” then “bell” luminaries (shown here). As the decades wore on Fifth Avenue received a separate style of Twin, the Type 1. Type 3’s also turned up on other NYC avenues, but their bailiwick was Fifth Avenue. They were Beaux Arts masterpieces with globes at the top of the shafts and springs at the apex and the tips of each mast.

Note, in the photo above right, that then as now, the city always didn’t match luminaire styles on the posts. Till the mid-1910s, streets signs were square plaques; after that, the well-known navy and white “humpback’ signs appeared. How quiet Fifth Avenue was in the early 1910s!

A very few Type 3’s made it as far as the 1980s, at 5th and 15th, 17th, and 25th. They have all vanished. One lone post, at the SE corner of 5th and 23rd and Madison Park, in front of the Seward statue, retains the Type 3 scrollwork, albeit on what looks like a Type 1BC bishop crook shaft and base. Photo below right, 5th and 15th, 1986, photo by Bob Mulero.

The Systems catalog identifies the post at left as a New York Electric Type 6 Twin. They had a much “busier” base, and a taller shaft, the better to spread light on major intersections. Only one of these exists today, albeit in a compromised fashion. As is the case with other old posts around town, some mixing and matching has been done, and in the case of the surviving post (center) at Amsterdam Avenue and Hamilton Place, a Type 24 Variation 3 was attached decades ago to the existing Type 6 Twin base. So, we have two extinct posts in one, since the variation, easily recognized by a sharp spike at the apex, is now totally absent in the city, except for here.

Bob Mulero snapped the post in 1978, but it is still there, albeit now fitted with a pair of unsightly sodium bucket luminaires. There were probably similar complaints about the Westy “cuplights” when they were installed in the 40s or 50s. It’s indeed a shame that gorgeous scrollwork on the original Type 6 wasn’t kept.

Early on, every NYC bridge (and there are hundreds of them) had a unique lamppost design on the approach roads. (Traces of them, in some cases, remain today). This was what the 145th Street Bridge approach loked like in the early 20th Century. They look like regular Bishop Crook lamps, but the scrollwork and base are completely different.

The City is in the process (as of 2007) of installing a new 145th Street Bridge that pretty much looks like the original. FNY visited in 1998 and turned up some ancient artifacts then lurking there.

When I spotted this strange post under the Bowery el in Rebecca Lepkoff’s excellent Life on the Lower East Side, 1937-1950, I was stumped at first. This elaborate, ornate scroll didn’t match up with anything in the Systems pamphlet, until I found this one: a special mastarm attachment to the Type 3 Bishop Crook post. It’s likely there’s a Bishop Crook out of the picture at the top. Unfortunately, the exact streets shown in the picture aren’t named in the book, but it’s quite possible the buildings and streets shown here are all gone. The Bowery-3rd Avenue el was razed in 1955, and we lost a wealth of ornate lampposts when it went.

Type C posts originated as gaslight posts in the pre-electric era. Two can be found flanking the front steps at India House at Hanover square in lower Manhattan. They bear modern sodium lights.

India House was the first home of The Hanover Bank. The structure today is one of the few pre-Civil War commercial buildings left in New York City. (The Hanover Bank merged with Manufacturers Trust Co. in 1961, and Chemical Bank merged with Manufacturers Hanover in 1991.) In 1914, the old Hanover Bank building was converted into a businessman’s luncheon club named “India House”; one of the club’s founders was J.P. Morgan employee Willard Straight. www.nyc-architecture.com Old photos show these posts have been there for quite awhile.

Downtown Brooklyn

In the early 20th Century Brooklyn had a set of distinctive posts all its own that didn’t resemble their Corvington cognates across the river in the least. For the most part these were confined to downtown and the neighboring Cobble Hill area. Their name, in the Systems book, was “Old Edison Post” and came in shorter, taller, and smaller variations, and had a variety of bases. Here’s one under the Fulton Street el. Note the Hearns ad, the Target of its day, in the background.

Top left: It’s 1940 and the Fifth Avenue el, which ran on Flatbush Avenue here, passed in front of the old Bickfords, but is quickly becoming scrap metal. The Williamsburg(h) bank building, now being converted to pricey residential units, looms in the back. BQT: Brooklyn and Queens transit, Harold A. Smith and Frederick A. Kramer

Center:, an older scene, likely 1910-1915, showing an Old Edison Post smaller variant, at Clark Street and Columbia Heights. Brooklyn Heights and Downtown: 1860-1922, Brian Merlis & Lee Rosenzweig

Right: catalog, Old Edison post

The “Bickfords” lasted until my high school years, which, er, um, is quite a few years ago now. (OK, the swingin’ 70s.) Old Edison posts were supplanted by Corvs and bishop crooks, and later by the new aluminum octagonal poles beginning in 1950. I could swear, though, as I was riding the B64 bus as a lad in the early 60s, I spotted one of these strange Old Edison posts. Lest you think I have too selective a memory, I can recall the one and only time my mother and I walked down Myrtle Avenue in the 60s. This was when there was an el, which I regret never having ridden. It was 1964. How do I know? “My Boy Lollipop” was playing on a passing car radio.

Pioneering photographer Berenice Abbott snapped a Type 3 Brooklyn Electric light on Montague Terrace, Brooklyn Heights, during her 1930s “Changing New York” series. This was another Brooklyn post that never made it across the river, though it resembled a Type G Corvington.

2/17/07