Since 1973, Mount Morris Park, located along Madison Avenue between East 120th and East 123rd Streets (it interrupts the northern progress of Fifth Avenue for 4 blocks) has been known as Marcus Garvey Park. The roadway that forms its western boundary is still called Mount Morris Park West, however, as is the immediate surrounding area in Harlem, and for Forgotten NY purposes, we’ll still call it Mount Morris Park. Native Jamaican Marcus Garvey (1887-1940) was a charismatic community leader in the early 20th Century who was an early promoter of African-American self-sufficiency; his goal was to found an independent country for African Americans in west Africa. He was found guilty of mail fraud, was deported to Jamaica in 1927 and died in exile. He remains a revered figure, however, for his founding of the UNIA in 1914 and as a promoter of social, economic and political freedom.

5th Avenue is interrupted by Mount Morris Park at 120th Street.

Long before the street grid marched north, followed by brownstones, streetcars and eventually, elevated trains and subways, land here was set aside for a park. Land for Mount Morris Park was dedicated by the city as early as 1839 when the hill was thought to be too high to level, as many other shorter hills had been as the city’s northen limit marched up Manhattan and the street grid was established. The promontory was known by the Dutch in the colonial days as “Snake Hill” for its native reptile population.

The last remnants of “Snake Hill” east of the park, a huge rock outcropping on Park Avenue between East 122-123rd Streets, were demolished in 1911.

Lenox Avenue (Malcolm X Boulevard) between West 123rd-124th Streets. Mount Morris Park, and Harlem in general, is NYC’s brownstone capital; although there are parts of Manhattan that can challenge Harlem for the title such as Chelsea and the Upper West Side, and parts of Brooklyn like Bedford-Stuyvesant and Park Slope, Harlem can boast miles of avenues and side streets that are lined with unit after unit of these attached buildings. Most are constructed from Triassic sandstone, with its distinctive brown color deriving from red ion ore contained in the mix. Most brownstones are between 20 and 25 feet wide, and because they were originally built for well to do residences, some of their interiors remain executed with fine materials and are elaborately apportioned and decorated.

There is no better way to view the gorgeous interiors of some of Harlem’s best brownstones than by consulting Michael Henry Adams’ excellent coffee table book, Harlem Lost and Found (Monacelli Press, 2002).

My favorite church exterior in the Mt. Morris Park area is the high-spired Ephesus 7th Day Adventist Church, constructed as the Reformed Low Dutch Church of Harlem by architect John Rochester Thomas in 1894-1895 at 267 Lenox at the NW corner of West 123rd. It has a bright Ohio sandstone surfacing that makes it stand out from its brownstone neighbors. The Boys Choir of Harlem was established here in 1968. The entire interior was laboriously rebuilt after a 1969 that also damaged the steeple, which was restored to its original state in 2006.

St. Martin’s Episcopal Church at West 122nd and Lenox, constructed in 1888 by architect William Potter, is one of the premier examples of Romanesque ecclesiastical architecture in NYC. Its tower contains 42 carillon bells, making it second only in number of carillon bells to Riverside Church (the world’s largest carillon at 74 bells), the only other church in Manhattan with a carillon. The bells were cast in 1949 with the smallest the size of a flowerpot and the largest, at two and a half tons, big enough to contain a crouching person.

Visit on Sunday morning, when I did, and you’ll hear the appealing pealing.

Much of the north side of West 122nd Street, known as “Doctor’s Row,” was constructed from reddish sandstone; 133-143, seen at right, are the work of Boston architect Francis H. Kimball (1845-1919), whose better-known buildings are the Reading Terminal in Philadelphia, the Montauk Club in Park Slope, Brooklyn, the Corbin Building on John Street and Broadway, and Edgehill Church in Spuyten Duyvil in the Bronx.

The buildings [Kimball] created at 133-143 West 122nd Street (1887) are astonishing. In less sure hands the brownstone lower stories would have seemed dour and old-fashioned. Similarly, the flame-colored brick and terra-cotta of the upper stories might have been a lurid disaster. However, this masterful row is a veritable frieze encrusted with a panoply of ornate devices to delight the eye. Michael Henry Adams, Harlem Lost and Found, linked above.

1880s, meet 2010s. Dystopian, eh? Jarring, to say the least, on West 123rd a block north of the Kimball brownstones.

Greater Metropolitan Baptist Church, 147 West 123rd.

Originally built as the German-American St. Paul Lutheran Church of Harlem, the Gothic church was built in 1897-98 by architects Ernest W. Schneider and Harry Herter. It became Greater Metropolitan in 1985. Count the steeples! Surfaced with Vermont marble.

A ghost street sign on this corner stately brownstone building at Mt. Morris Park West and West 122nd gives a clue to its date of construction. Mount Morris Park West was known as Mount Morris Avenue between 1878 and 1893.

The Mount Morris Ascension Presbyterian Church, MMPW and West 122nd, was originally the Harlem Presbyterian Church, as shown by the medallion depicting Noah’s ark on the exterior. Its verdigris’ed dome seems out of place, as it can be best viewed from the summit of Mount Morris. It was designed by Thomas H. Poole (one of his few Protestant commissions; he usually designed Catholic churches) and completed in 1906, and is the ‘newest’ Romanesque church in Harlem. It alternates granite with bands of brown brick:

… Poole’s … almost Byzantine edifice was everything that the old churches were not, and like no other in the city. In place of the brownstone used before, Poole designed a striking combination of yellow-orange ironspot Roman brick, smooth bluestone, and rock-faced granite. Rather than projecting overly ambitious towers with tall stone steeples, he employed a more affordable copper-clad dome (the first of only three in Harlem). Michael Henry Adams, Harlem Lost and Found; cf. for a spectacular interior picture

If you haven’t yet gotten the idea that Harlem is filled with spectacular churches here are two more:

Ebenezer Gospel Tabernacle, Lenox, NW corner West 121st. Formerly a synagogue, and before that, the Lenox Avenue Unitarian Church, built 1889-1891 by Charles Atwood, later a partner of Chicago’s famed Daniel H. Burnham.

Mt. Olivet Baptist Church, originally Temple Israel, Lenox at NW corner West 120th, some of the biggest Ionic columns in the city. Completed in 1907 by Arnold W. Brunner.

West side of Mount Morris Park West between W. 120th and W.121st. The row of brownstones shown have been recently restored…

1-5, constructed in 1893, architect Gilbert A. Schellenger;

6-10, 1891, James E. Ware.

The Only Shea Stadium Left

Though Shea Stadium in Flushing Meadows was razed in 2009, William A. Shea (the attorney who helped bring National League baseball back to NYC) is still remembered by this ballfield at Mt. Morris Park West and West 121st Street.

It all started when Harlem Little League founders Dwight and Iris Raiford received a letter from Bill Shea in September of 1989. Shea, then the longtime president of the Little League Foundation, wanted to know what he could do to help the Harlem branch. Dwight Raiford had never met Bill Shea, but knew of his law firm, Shea and Gould, and knew that the name ran along the top of a stadium in Queens.”What we really need is a ballfield,” Raiford told Shea. “A field of our own.”

The Harlem Little League, which played its first season in the spring of ’89, was already overflowing with kids and was forced to turn many away, says Raiford. Raiford desperately needed a kids-only park to handle the massive turnout and become the permanent home for his league.

Shea helped raise money. He worked with the parks department and local politicians. He helped turn a run down asphalt eyesore in Harlem, lousy with broken bottles, into a graceful ballfield of green grass and groomed earth complete with dugouts and bleachers – and this summer they will add a clubhouse.

“It’s a first-class facility that shows these kids that the community cares about them,” says Raiford. “It was not about money or power. It was about getting something done for people….We can use a little bit of suburbia in Manhattan, and that’s what we get at Shea Field.”

Mets owner Fred Wilpon, a longtime friend of Shea’s, got involved as well. “Bill was so interested in Little League, especially Harlem Little League,” says Wilpon. “We made sure his name would be on the field.” Shea never got to see Shea Field and the impact it had on the neighboring streets. He died in the Fall of 1991, eight years before the grand opening in 1999, ten years after he sent the letter that got everything started, the letter Dwight Raiford still has. NY Daily News

“Harlem Court House”

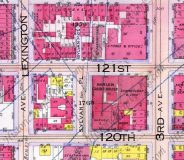

Walk east a couple of blocks on East 121st from Mount Morris Park — between Lexington and 3rd you will find a majestic, Gothic and Romanesque building standing beside a park. Presently the Harlem Community Justice Center, it has had many functions…

Built from 1891-1893 by the architectural firm Thom and Wilson The Harlem Court House has been the 9th District Civil Courthouse, the 5th District Prison (I haven’t been able to reconcile the two numbers — anyone know?), a magsitrate’s court, and a small claims court. Inside you will find some WPA murals from the 1930s. The courthouse was given landmark designation in 1967. NYC.gov has an interior photo.

Sylvan Court

Sylvan Court has not appeared on most city maps for at least a few decades, but its less interesting cousin, Sylvan Place across the street from it on East 121st, a city park adjoining the Harlem Courthouse, does. Sylvan Court, though, is much more fascinating as a bit of urban archeology…

If one is interested in seeing a quaint bit of Old Harlem it will be found just one block to the south and less than two blocks to the east from [Snake Hill]. As one walks through 121st from Lexington Avenue he will discern in the middle of the block a little street extending only to 120th street and known as Sylvan Place. A continuation of this ancient street to the north is designated by an iron arched sign as Sylvan Court. The court is really a blind alley, as it ends in the middle of the block, but there are several old-fashioned brick houses on both sides of the court and the entire atmosphere of the locality reminds one of some of the half-forgotten spots occasionally found in the Greenwich Village district. — New York Times, August 20, 1911

The Times article from 1911 — almost a century ago [in 2009] is still as true today; Sylvan Court is one of those few Manhattan alleys that has survived more or less unchanged, and it is truly a surprise if you’re not looking for it. Some of the brick homes are in better shape than others, but residents here appear to take pride in their unheralded cul-de-sac.

Sylvan Place

Though the Times described Sylvan Court’s houses as “old-fashioned” in 1911, the court was relatively new then, as Sylvan Court doesn’t appear on area maps until 1908 or so…

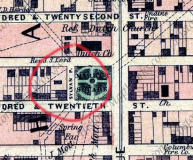

LEFT: 1867 Dripps atlas shows Sylvan Place already there, but its northern extension, Sylvan Court, not yet. A similar atlas from 1887 also shows Sylvan Court absent. a 1908 Belcher Hyde atlas, right, shows both in place by that time. Thus, Sylvan Place is older than Sylvan Court by 40 years or so.

Sylvan Place is today a park adjoining the old Harlem Court House. It’s rather less interesting than Sylvan Court, with its quaint houses. Yet, it has an interesting lineage. Let’s return to that 1911 NY Times article…

Sylvan Place is a remnant of the old Church Lane*, and it is still possible to see the line of the lane by the curious shape of the brick stable on the northwest corner of Lexington Avenue and 119th Street…

*For an explanation re Church Lane we turn to Gilbert Tauber’s oldstreets, a compendium of the hundreds of Manhattan streets and roads that have vanished from maps over the decades…

Church Lane . (L17-M19**) A street in the old village of Harlem. Earlier called the Great Way, it was renamed after the opening of the Dutch Church at Harlem about 1665. It ran from southwest to northeast, passing diagonally through what is now the intersection of First Avenue and East 125th Street.

**In Tauber’s nomenclature, L17-M19 means that Church Lane can be found on maps dating from the late 17th Century to mid-19th.

In fact, 19th Century maps indicate that Sylvan Place now sits on what was once the confluence of two major Manhattan roads in the colonial era, the Eastern Post Road (which was the northern extension of the Bowery and once was a major coach road to Boston) and the Kingsbridge Road, which crossed to the Bronx over the bridge for which it was named. Quite a pedigree.

Of course, neither Sylvan Place nor Sylvan Court should be confused with Sylvan Terrace, that picturesque string of row houses in the shadow of the Jumel Mansion in northern Harlem.

Mount Morris Park

The name Morris turns up frequently in northern Manhattan and the Bronx. Though we’ve seen that the Bronx locales are named for the prominent Morris political dynasty (see To Have and Have Mott) the origin of the name Mount Morris Park has apparently been a puzzler for historians. A Robert H. Morris was NYC mayor from 1841-1844, but the park had been established by then. Sanna Feirstein of Naming New York guesses that the park’s high elevation gave a good view of the Morris holdings across the Harlem River to the northeast.

The schist outcroppings of what was once Snake Hill are in evidence here. They can be found all over the streetscape in northern Manhattan and the Bronx, and turn up in some unexpected spots that are otherwise highly urbanized.

Ascending the steps to our next stop, I noticed a couple of 1960s-vintage SL200 luminaires. Very rare now, they held green-white mercury bulbs. They also hold a pair of brighter sodium yellow lamps to light the steps.

Mount Morris Fire Tower

Before electric lights, radio or fire alarms, when a fire broke out, you had to make a lot of noise on your own to alert the local population. Blazes were fought by volunteer fire departments, which were poorly coordinated and organized, until 1865, when the New York state legislature replaced the volunteer companies with the Metropolitan Fire Department. (The Fire Department of New York would succeed it in 1870.)

Until the fire companies acquired a telegraphic alert network in 1874, they relied on watchmen in lookout towers that were built on hills in Manhattan. The Mt. Morris fire tower is the last of its kind in NYC and the last one of its kind remaining in the USA.

Many of these towers were made of wood, and did not stand up to the elements over the years. This one, built by Julius Kroehl in 1856, is made of cast iron while the design is based on earlier towers by James Bogardus, who had built earlier such towers on 33rd street near 9th Avenue and Spring Street near MacDougal that disappeared decades ago.

How did the fire towers work? When a blaze was spotted, the watchman would then ring the bell, with different pealings indicating different neighborhoods. He would also use signal flags during the day to alert a nearby fire company. The invention of the telegraph by Samuel Morse was the first step in modern fire alerting.

The tower’s 5-ton bell was cast by founders E.A. and G.R. Meneeley of West Troy, N.Y in 1865, replacing the original 1855 bell. According to EastHarlem.com, the Mt. Morris bell continued to sound even after more modern fire alarms were installed: at noon and at 9:00 pm weekdays and 9:00 am and 9:00 pm on Sundays for timekeeping and church purposes until about 1909.

Unfortunately, the concrete plaza that houses the tower and serves as a lookout point for the entire neighborhood is abandoned, at least in the winter months, and in disrepair.

Current facilities include the Pelham Fritz Recreation Center, named for a reknowned Parks employee, an amphitheater and a swimming pool. Capital projects completed in 2002, 2004 and 2005 have improved the pool entrance, added new safety surfaces and landscaped the park. The Marcus Garvey Park Alliance community group organizes a variety of cultural events in addition to supporting capital projects. NYC Parks

“Forgotten” 5th

5th Avenue, cut off from its “Queen of Avenues” stretch south of the park, runs another 18 blocks or so until Manhattan’s geography cuts it off at the Harlem River. You’ll find a number of surprises just north of the park…

St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church, NE corner 5th and East 127th, originally completed in 1873 but enlarged to present size in 1890, Henry M. Congdon, architect. The side entrance is actually on the avenue with the main entrance on 127th. The parish has been in existence since 1829 — this church replaced a wood church on 127th between Park and Lexington that burned down. The new church was built there and was subsequently dismantled, reconstructed, and expanded at its present location.

New condo, NE corner 5th and East 128th. This is actually better than most new construction around town, though no effort was made to fit it in with its neighbors.

A small green space on the NW corner of 5th and West 128th is all that remains of the former abode of Homer and Langley Collyer, a brownstone row house on the corner that the two brothers had occupied for 38 years between 1909-1947. They had moved to the house with their parents, gynecologist Herman Collyer and his wife Susie; the doctor abandoned his family in 1919, passed away in 1923, and the two sons inherited their parents’ possessions and moved them into the 5th Avenue brownstone. Both brothers were Columbia University graduates, Homer earning a degree in admiralty law and Langley a degree in engineering, though he also apparently aspired to be a concert pianist.

After a series of attempts to burglarize the building by outsiders the brothers became increasingly reclusive, boarding up the windows, never throwing out any accumulated possessions and even setting elaborate booby traps to foil any intruder. Eventually they had collected numerous pianos, thousands of newspapers, and a model T Ford (living without gas or electricity, Langley had rigged up a generator from the car engine). Homer suffered a crippling stroke and lost his sight, forcing Langley to scour the neighborhood for scraps or cheap food, with water being obtained from Mt. Morris Park fountains. The brownstone became suffused in squalor with dozens of stray cats, rodents and other vermin. The two brothers were finally found dead in the apartment in 1947; Langley had fallen victim to one of his own booby traps while Homer died of malnutrition. It took weeks to find his body amid all the accumulated junk. The authorities followed the stench.

Items removed from the house included baby carriages, a doll carriage, rusted bicycles, old food, potato peelers, a collection of guns, glass chandeliers, bowling balls, camera equipment, the folding top of a horse-drawn carriage, a sawhorse, three dressmaking dummies, painted portraits, pinup girl photos, plaster busts, Mrs. Collyer’s hope chests, rusty bed springs, the kerosene stove, a child’s chair (the brothers were lifelong bachelors and childless), more than 25,000 books (including thousands about medicine and engineering and more than 2,500 on law), human organs pickled in jars, eight live cats, the chassis of the old Model T Langley had been tinkering with, tapestries, hundreds of yards of unused silks and fabric, clocks, fourteen pianos (both grand and upright), a clavichord, two organs, banjos, violins, bugles, accordions, a gramophone and records, and countless bundles of newspapers and magazines, some of them decades old. Near the spot where Homer died, police also found 34 bank account passbooks, with a total of $3,007.18. wikipedia

Scroll to the bottom of this Police NY page for pictures of the interior of the Collyer place as the cops found it.

Variety. 11, 15, 17, 19 East 128th Streets. 11 is asymmetric, while 17, my favorite, is the oldest, a wood clapboard house constructed in 1864. 17 was occupied for many years by Carolyn Adams, a prominent dancer and choreographer with the Paul Taylor Dance Company. The house and its environs are described in detail at this Neighborhood Preservation Center webpage.

Harlem Renaissance High School is located across the street at 22 East 128th. When it was PS 24, author/playwright James Baldwin (1924-1987) attended school here.

Rapunzel, let your hair down from the corner turret at 2068-2076 5th at the SW corner of West 128th.

Another of the neighborhood’s old country houses, this one at 12 West 129th Street, constructed about 1863, boasts a Moorish style porch added in 1882. There’s a separate pavilion on the driveway out in the back. It was close to abandonment in 1991, but it has since been restored as a hostel called Jazz on the Villa.

St. Ambrose Episcopal Church, 15 West 130th Street, is a Gothic Revival composed of rock face granite. The church’s congregation was originally the Second Presbyterian Church of Harlem, but as the price of its construction in 1878 church members decided to accept benefactor Rev. George B. Cheever’s gift, provided that the name be changed to the Church of the Puritans — the older one, in Union Square, had been acquired by Tiffany and Company for a new store. I am unsure when the parish became St. Ambrose.

Cheever and Tiffany. When have I heard these two names together before? In Brooklyn, where Cheever and Tiffany Places run on either side of Hicks Street between Kane and DeGraw in Cobble Hill. Is there a connection? Unfortunately not. While tiffany Place is indeed named for Tiffany founder Louis Comfort Tiffany, Cheever Place is named for Samuel Cheever, a commissioner who helped lay out Brooklyn’s streets.

Astor Row

Comprising the southern part of West 130th Street between Fifth and Lenox, Astor Row, built by architect Charles Buek between 1880 and 1883, features an extreme rarity in Manhattan: houses with porches.

Built on land owned by William Astor (great grandson of fur entrepreneur John Jacob Astor and scion of his real estate empire), Astor Row is made up of 28 brick houses, attached in pairs. Since 1992 great strides have been made toward rehabilitating them. in that year, the NYC Landmarks Conservancy in association with the Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Abyssinian Development Corporation began the ongoing project to reverse the deterioration and restore Astor Row.

Just a couple of the Astor Row buildings still await restoration.

Good sign. Public Fish Market, Lenox Avenue (Malcolm X Blvd) and West 131st.

“Rococo” is a word you can use to describe St. Aloysius [allo-ISH-us] Roman Catholic Church at 209 West 132nd between Adam Clayton Powell and Frederick Douglass Boulevards. It boasts possibly the ‘busiest’ and most elaborate terra cotta work on any church in the city. It was constructed in 1904 by architect William W. Renwick, the nephew of James Renwick, architect of St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

The façade, considered one of William W. Renwick’s most important commissions, consists of alternating bands of red brick, celadon-colored glaze brick and glazed “granitex” (with the color and texture of gray granite) terra cotta with cobalt blue accents. NYC.gov.

St. Aloysius was granted NYC Landmark status in 2007.

Been getting ever darker since the walk began –check the top of the page. Time to get started back to Forgotten HQ in Little Neck at the IND 135th Street station, which received a unique station entrance at St. Nicholas Park.

SOURCES: Harlem Lost and Found; Blue Guide to NYC, Wright, Seitz and Miller; AIA Guide to NYC, White and Willensky.

Photographed April 2009; page completed May 3, 2009

erpietri@earthlink.net

©2009 FNY

2 comments

[…] grandparents would take us to Mount Morris Park, small in acreage, but so central to all children living close by. My aunt, Katherine, lived on […]

[…] stated on FNY’s Mount Morris Park page, the origin of the name Mount Morris Park has apparently been a puzzler for historians. A Robert […]

Comments are closed.