Has it been two years since I began my Bedford Avenue survey with a walk along its entire length from Emmons Avenue in Sheepshead Bay north to its beginnings at Manhattan Avenue in Greenpoint? It doesn’t seem that long, but there it is. This summer I finally completed that walk, in two sections, and I’ll show you the midsection of Bedford Avenue today and the northern section sometime soon. The name of Bedford Avenue is in some dispute — the avenue originally ran through the neighborhood of Bedford (now the western section of Bedford-Stuyvesant) which was either named for England’s Bedfordshire or the Dutch Bestevaar, “meeting place of old men.” Bedford Avenue was assembled piecemeal from the original road through Bedford, the annexation of a northern section in the City of Williamsburg(h) formerly called 4th Street, and the southern section was gradually extended south during he late 1800s and early 1900s.

A ForgottenFan who makes all the tours (feel free to send me your name again!) calculated by driving down both Bedford and Flatbush Avenues that Bedford Avenue is indeed the longest street in Brooklyn, beating out its rival by about a half mile or less. Its neighbor to the east, Nostrand Avenue, is also quite lengthy (though it does not extend into Williamsburg as does Bedford). Other lengthy Brooklyn avenes such as Myrtle and Metropolitan Avenues run east to west and so, much of their lengths are in Queens.

So, where was I? I left off in the center of the old town at Flatbush at Beverl(e)y Road and the Brooklyn’s own iconic Sears Tower, not quite as tall as the one in Chicago but, in fact, it has acquired a uniqueness of its own since the Windy City’s Sears Tower was renamed in 2009 and became the Willis Tower for the British insurance broker that leased a good part of the building. So, it might be said that Brooklyn can now claim the Sears Tower. This building was constructed in 1932 with Eleanor Roosevelt turning a ceremonial key and was the first Sears, Roebuck outlet in New York City. North of the Tower, Bedford Avenue takes on a mixed commercial-residential outlook. These attached homes with bayed windows are between Bedford and Tilden Avenues.

Michelle’s Restaurant is on the SW corner of Bedford and Albemarle Road — I noticed the vintage red and white enamel Coca Cola sign on the side of the building. It’s missing the Coke “swash”, so it’s older than the 1970s at least.

Not much more than a warehouse now, this is the former headquarters (NW corner Albemarle and Bedford) of Brooklyn’s most famous bakery, Ebinger’s, literally a household name for decades in Brooklyn until the early 1970s.

Under Mayor Bloomberg’s Department of Transportation commissioner, Janette Sadik-Khan, dedicated bicycle lanes have become more than an afterthought around town, and some lanes have received protective curbs, buffer zones and new paint jobs. Many of these have been installed in tonier neighborhoods, and the Bedford Avenue lane, which I used frequently while living in Brooklyn, remains as sketchy as ever.

Perspectives on bike lanes are always interesting reading: try Aaron Naperstek’s Streetsblog, Brooklyn By Bike, and for an opposing view as to their worthiness, Commuter Outrage.

PS 6, a relatively new school building (appears to be from the 1970s or 1980s) at Snyder Avenue. Across the street is the Get Set kindergarden, with murals illustrating the worthiness of books — we will see more murals later.

Unusual doorway, 2255 Bedford, The Alexander. RIGHT: Woods Place, in the original village of Flatbush, is one of its many short side streets in the neighborhood such as Lott Place, Johnson Place, Oakland Place and Veronica Place, all of which only run one block.

I don’t know why 2245 Bedford, just south of Erasmus Street, is called the Madison Square Boys & Girls Club — I had thought it was an obscure section of Brooklyn. The borough does have a small section called Madison, but it’s north of Avenue U and west of Gerritsen Avenue north of Sheepshead Bay. RIGHT: Universal Church of the Kingdom of God, Erasmus Street.

The back end of the venerable Erasmus Hall High School can be seen from Bedford and Erasmus Street. C.B. J. Snyder’s magnificent 1905-1906 building surrounds the much older original Erasmus Hall Academy building, constructed in 1786. I’ll have more on Erasmus Hall on a future post encompassing the school’s original sponsor, the Flatbush Reformed Dutch Church. Names as disparate as Alexander Hamilton, his assassin Aaron Burr, Bobby Fischer, Neil Diamond and Barbra Streisand have been associated with the academy and later high school across the centuries. Erasmus Street and the former surrounding neighborhood, Erasmus, now absorbed into Flatbush, were named for Dutch scholar/philosopher Desiderius Erasmus (Gerhard Gerhards, 1466-1536). A statue of Erasmus can be found outside the original academy building in the courtyard.

The terra cotta Ellsworth Building, NW corner Bedford and Church Avenues, echoes the terra cotta construction of Erasmus Hall High School.

LEFT: porched house, Church Avenue east of Bedford.

Flatbush Village Relic?

The building on the SW corner of Church and Bedford has always mystified me — it’s been abandoned for many years.

This was once the Flatbush District #1 School, later PS 90, and was constructed in 1878 by John Culyer, also the architect of Flatbush Town Hall on Snyder Avenue — actually a designated Landmark.

This building on Bedford Avenue near Martense street grabbed my attention because it was apparently signed by its architects with the monogram MNW. Could this be Malkind and Weinstein, who similarly mongrammed a building of theirs on Court Street? The inclusion of an “N” casts doubt on that, though it’d be a hoot if it was indeed the same firm.

Buildings on Linden Boulevard (above left and right) and Caton Avenue (left). Linden Boulevard, one of the longest streets in NYC, extends from Flatbush Avenue to Elmont, Nassau County, interrupted for a few blocks on Ozone Park and Aqueduct Raceway. Like many of NYC’s longer roads, it is an amalgam of several roads; it incorporates the former Vienna Avenue in East New York and Central Avenue in eastern Queens. Caton Avenue and LInden Boulevard are part of NYS Route 27, which ultimately travels to eastern Long Island via the Sunrise Highway. A mere two lanes here, Linden Boulevard becomes a powerhouse after absorbing traffic from Kings Highway a coupel of miles east.

Many area streets were named for members of the same family: Martense Street for early Flatbush Village landholder Joris Martense, (1724-1791) who promoted Erasmus Academy; his daugher Susan Martense Caton; and her son-in-law, Philip Schuyler Crooke.

A pair of homes on Bedford Avenue north of Caton Avenue look much as they did several decades ago.

Berserk Eclecticism

Do you have a copy of the AIA Guide to New York City 1988 edition? Take a look at the photo of 111 Clarkson Avenue, just east of Bedford Avenue — it’ll break your heart. The late Elliott Willensky and his partner Norval White described it as “A fairyland place that might be termed berserk eclecticism. The onion domes are redolent of John Nash’s Royal Pavilion at Brighton (England, not Beach).” Since that time a modern enclosed porch has been installed and a business, I was told by a passerby, is still loacted there. But the onion domes as well as the rest of the building have decayed horribly.

From the NY Times: Built in 1902 by Herman Raub, a brewer, it may look like a near wreck to passers-by, but inside it has been preserved, even burnished, by its longtime owner, Raphael Berger.

Mr. Raub’s Consumer’s Park Brewing Company made him rich and influential among the gentry of German Brooklyn, and in 1901 he began work on a new house at 111 Clarkson, just east of Bedford Avenue in central Flatbush. Although established New York architects like John J. Petit and George Palliser were active in the area, Mr. Raub retained a complete unknown, Hugo von Wiedenfeld, a recent Austrian immigrant.

For an architect working in the rather placid waters of suburban house design, Mr. von Wiedenfeld had an unusual background. He was born in Vienna in 1852, trained there and in Aachen, Germany, and established his own practice in Vienna in 1884. He designed several remarkable buildings in and around Vienna, like the factory for the Zacherl family’s insecticide business, a striking polychromed brick building with pointed arches, minarets and a dome, explicitly Islamic in style.

Through the exterior damage and decay, it is still possible to see much of Mr. von Wiedenfeld’s fantastical three-story concoction.

Its roof planes are akimbo, like a Cubist avalanche. The front portico lunges out from the complex massing, while an open balcony on the third floor bursts through the roof like a jack-in-the-box. Unlike the neo-Georgian and other conventionally styled houses then popular in the neighborhood, Mr. Raubís was topped by four-sided domes, pointed towers and jerkin-head gables, where the point of the roof is cut off at a slant.

The front yard is now choked with weeds, but the fence, a wonderful curved loping thing of filigreed iron, remains intact. Two triplet panels of figured stained glass survive on the front and side walls, but a leaded glass panel near the front door has been smashed, the lead cames hanging down like wet noodles.

The earliest known photograph, dating from 1940, shows the porch and house painted in contrasting colors, and it is tempting to speculate on how much of the spectacular polychromy of the Zacherl factory Mr. von Wiedenfeld persuaded his Brooklyn client to adopt.

In September 1902 the nearby Cortelyou Club sponsored a fair, “a regular upstate pumpkin show,” according to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Mr. Raub offered to create a Little Germany by adapting two old barns into “a Fatherland beer garden.” He cooked the food himself and hired a women’s orchestra and the Tyrolean Warblers to entertain.

But Mr. Raub contended that the organ on a nearby carousel was competing with his musical offerings. “The air was thick with threats,” The Eagle reported, and when the head of the fair took the side of the carousel owner, Mr. Raub packed up his Little Germany and left abruptly.

Mr. Raub died sometime before 1930. That year’s census recorded that his widow, Phillipine, was living at 111 Clarkson with her two daughters. The house and its stable were valued at $50,000.

Things have gone downhill since then. Most of the slate roof is gone, replaced by modern shingles. Pigeons fly in and out of the dormer windows, past fragments of stained glass; the balustrade at the third floor looks as if it would fall over in a breeze; and the eight-sided dome over the portico has somehow been squashed, like a tin can under a giantís foot. Worst of all, the arcaded wooden porch has been reconstructed in brick, or perhaps fake brick, with smoked-glass picture windows.

Mr. Berger has owned the Raub house since the 1980s and uses the remodeled front porch as his law office. This spring, he courteously received this unannounced visitor and offered a hurried walk through the ground floor.

This left fragmentary impressions: a parlor with the walls and ceiling covered by baroque murals; a paneled dining room with Gothic-style chairs; and a double-height central foyer ringed by a staircase rising to the second floor. Everything was neat and well kept, at utter variance with the exterior.

Subsequent requests for an interview were met with polite refusal. “I don’t know if I want any notoriety,” Mr. Berger said recently by telephone. “I don’t want to have a lot of people coming by; I have enough of that,” he said. “I’m really not interested in having it designated a landmark or anything.”

Two visions of Parkside

Facing each other on Parkside and Bedford Avenues we see two visions of multifamily housing, one from the 1890s and the other from the early 2000s, one mansarded and dormered, the other blank-faced and Feddered.

Native Rhode Islander H. P. Lovecraft moved to Parkside Avenue (a couple of blocks away in an apartment building at 259, still standing) in 1924 soon after marrying Sonia Haft Greene. His stories from the period, such as The Horror at Red Hook, are redolent with characters having Brooklyn street names such as Martense.

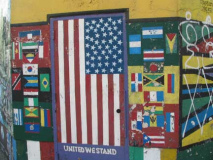

Another mural, this one on a day care center on the NW corner Parkside and Bedford Avenues, completed in the summer of 1991, sponsored by Mayor David Dinkins’ Safe Streets Safe City initiative. The program earmarked new taxes to fund the hiring of thousands of new police officers and criminal justice workers. The increase in the Police department permitted Dinkins’ successor, Rudy Giuliani, to implement zero-tolerance policy on quality of life issues; this “broken-windows” approach led to the capture of criminals that otherwise would have been free to commit more serious crimes. Overall, crime dropped dramatically in NYC duyring the 1990s, with annual murders dropping from over 2200 to under 600.

Despite Dinkins’ Safe Streets Safe City initative he lost narrowly to Giuliani in 1993 due in large part to his perceived powerlessness to prevent the Crown Heights Riots in August 1991 and perceived inability to do anything about them once they started.

From its website: The Crown Heights Youth Collective is a multidimensional, self development program located in Central Brooklyn. Since its inception in 1978, over 100,000 residents have benefitted from its educational, cultural, social programs and the Rights of Passage project. We established many Peace Zones throughout the borough, the community beautification gardens, development of agricultural gardens, feeding of the community and beautification through murals instead of graffiti. The agency’s co-founders Dr. Robert H. Johnson, Dr. Myrah E. Brown Green and Mr. Richard E. Green perceived the need for advocacy and service oriented organization to stem the tide of urban decay. Its trust was toward a renewed excellence and the establishment of community progress. The founders realized that a basic catalyst for change lies in the upliftment and reaffirmation of the aspirations of youth.

Prospect-Lefferts Gardens

ABOVE, LEFT: Bedford Avenue and Hawthorne Street. North of Parkside Avenue Bedford Avenue changes character again, as it runs through the heart of Prospect-Lefferts Gardens (encompassing Lefferts Manor), called by the Landmarks Preservation Commission “one of the finest enclaves of nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century housing in New york City.” In 1873 a local landowner, James Lefferts, subdivided his holdings into 600 separate lots and sold them to developers, who built several blocks of row houses and also some free-standing homes. Prospect-Lefferts Gardens, as the region came to be known, has been home to Caribbean Americans for the past few decades.

ABOVE LEFT: Maple Street; above right: Lincoln Road; Left: Grace Reformed Church, Bedford and Lincoln Road. Grace Reformed Church was initiated in 1856 by Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt, meeting at first in what is now Prospect Park. Its present building was erected in 1893.

Lincoln Road is the first of a number of tributes to Abraham Lincoln that Bedford Avenue encounters as it marches north.

Ebbets Remnants

I’m one Brooklyn native not reminiscent about the Brooklyn Dodgers, since the Dodgers were in Brooklyn only just over once month of my life in 1957. The Dodgers, also known as the Robins for a few years, played at the stadium owner Charles Ebbets built for them in the block surrounded by Bedford Avenue (the outfield fence), McKeever Place, Sullivan Place and Montgomery Street from the 1913 to 1957 seasons; before the Jackie Robinson era began in 1947, their time at Ebbets was mainly a period of futility marked only by 3 National League pennants in 1916, 1920 and 1941.

During the Robinson era he was joined by Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Don Newcombe, Carl Furillo and many other stars, and the Dodgers had an enviable run of domination in the National League. For the most part, they were stymied by the New York Yankees, their sole opponents in the World Series in those years, with the sole exception of 1955 when the unheralded Johnny Podres defeated the Bombers in the 7th game. The Dodgers sufered declining attendance and when plans for a new stadium downtown were thwarted by Robert Moses, Dodgers’ owner Walter O’Malley made the business decision to accept an offer to move the club to Los Angeles — where the Dodgers almost immediately won the World Series, defeating the Chicago White Sox in 1959.

Bedford Avenue and Empire Boulevard in the 1940s. The grandstand of Ebbets Field can be seen in the background. Note the building in the left foreground….brooklynpix

That building is still there in this 2009 photo, and it may have been a Firestone distributorship as far back as the 1940s when the older photo was taken. Both Ebbets Field and the Dodgers’ enemies, the New York Giants’ homes have both been taken over by housing projects, Ebbets Field Houses and Polo Grounds Houses in upper Manhattan. Ebbets Field was razed in 1960 while the Polo Grounds became the temporary home of the New York Mets, surviving till after the 1963 season. A single staircase that took spectators from the Polo Grounds up Coogan’s Bluff remains. A post 9/11/2001 mural can be sen north of the Firestone shop.

North of Empire Boulevard, Bedford Avenue enters Crow Hill, the southern reaches of Crown Heights. According to legend, prisoners in the old Brooklyn House of Detention, which stood on the block surrounded by Rogers and Nostrand Avenues and by Carroll and Montgomery Streets from 1848-1907, were called “crows” by the locals. The old prison site is today occupied by St. Ignatius Church (left); Brooklyn Prep also stood here, until 1973. RIGHT: storefronts, Rogers Avenue and Crown Street

Crown Heights, marred by riots (see above link) sparked by the death of a boy named Gavin Cato after he was accidentally struck by a car driven by a Hasidic Jewish driver in a motorcade in August 1991, has since stabilized and is now a largely peaceful community. It is the scene of a colorful parade on Eastern Parkway every Labor Day.

A pair of lookalike apartment entrances, Crown Street between Bedford and Rogers Avenues

Medgar Evers College, Bedford Avenue and Carroll Street. The college was established July 30, 1970 and is the youngest branch of the City University of New York. Evers (1925-1963) was a Mississippi civil rights activist and president of the regional Council of Negro Leadership, which in 1953 initiated a boycott against service stations that prohibited African Americans from using their restrooms. He later campaigned for the integration of the University of Mississippi. Having become a prominent voice, he became subject to threats and intimidation from whites in the deep South. On June 12, 1963 he was murdered by gunshot by Ku Klux Klansman Byron de la Beckwith, a crime for which de la Beckwith was not convicted until 1994. Evers is interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

Armory #1

The first of two NY State armories found on Bedford Avenue going south to north is on the east side of the avenue between President and Union Streets. Troop C Armory was constructed between 1903-1907 by Pilcher and Tachau. Troop C was a cavalry unit mustered during the Spanish-American War in 1898 and was originally housed in the North Portland Avenue Armory in Fort Greene. This armory remains active as a headquarters for the National Guard. Information from New York’s Historic Armories: an Illustrated History by Nancy L. Todd.

A pair of battered public phones on Bedford Avenue and Eastern Parkway. I could be wrong, but I have never felt that Eastern Parkway is quite as interesting architecturally as the other broad Olmstead and Vaux Brooklyn roadway masterpiece, Ocean Parkway (and it ends at Utica Avenue, whereas Ocean Parkway ends at Coney Island Beach), but I do plan to explore each.

Savoy Theatre, 1515 Bedford Avenue at Lincoln Place, now Charity Neighborhood Baptist Cathedral. It was constructed in 1926 by theatrical architect William Fox, who also built the larger Fox Theatre at Flatbush Avenue and Fulton Street. It had 2700-3000 seats. The church has pretty much left the interior intact except for a coat of whitewash.

Is the Studebaker Building on the NE corner of Bedford Avenue and Sterling Place the most beautiful building on Bedford Avenue? It’s been noted in FNY before. It is one of the last survivors of an automobile showroom row on Bedford Avenue, constructed in 1920 by Tooker and Marsh. Studebaker had moved out by 1939 and has been a dress store and showroom, a furniture manufacturer; later, a church occupied the ground floor; and in 1999 it was finally converted to residences.

Another building with very odd ornamentation is directly across the street from Studebaker on Bedford Avenue, with a motif depicting a long-bodied, scaly monster with small claws relative to the rest of the dragon. It can only be … the Danish Destroyer … Reptilicus!

The AIA Guide: “Loehmann’s (women’s apparel) , 1476 Bedford Ave., NW cor. Sterling Place, Crown Heights. Until it went out of business at this location, this chaotic store, wrapped in gilded Oriental detail, was filled with unbelievable bargains. A wonder to little boys who watched the scene in awe – Loehmann’s had no fitting rooms for mother! Some Chinese dragons still lurk on Sterling Place.”

Brownstoner’s Montrose Morris on Loehmann’s

The Delphina, Sterling Place west of Bedford, also bears its date of construction on the facade, 1908.

Carimar Food, Sterling Place; Brooklyn Beverage Barn, St. Marks Avenue, in a smaller former auto showroom.

Before showing you some truly wondrous architecture at Grant Square, here’s some crap-tacular stuff of recent vintage on Bedford Avenue north of St. Mark’s Avenue.

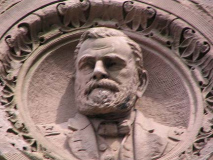

Bedford and Rogers Avenues form a triangle with Bergen Street, and this gave the city of Brooklyn an opportunity to do something special – and in 1896, that meant erecting a monumental, heroic portrait sculpture of President Ulysses S. Grant. It’s the largest such in Brooklyn, sculpted by William Ordway Partridge.

Grant has a pair of magnificent memorials in NYC, this one and Grant’s Tomb in Manhattanville. Ironically Grant, born in Ohio, defeated two New York Democrats in his two Presidential races, NY State Governor Horatio Seymour in 1872 and then Horace Greeley in 1876. Another mounted portrait of U.S. Grant can be found on the Soldiers and Sailors Monument Arch in Grand Army Plaza, across from the only mounted statue of Abraham Lincoln. Two great Confederate generals, Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, served at Fort Hamilton in the 1840s.

The triangle is called Grant Gore by the NYC Parks Department. It is not a co-tribute to former Vice President Al Gore; rather, the word refers to a small triangular park, taken from the word’s original meaning of a small odd-shaped or triangular piece of material sewn into clothing to alter the shape. Another such “gore” can be found in East Williamsburg at Metropolitan and Maspeth Avenues.

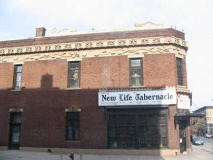

Washington Temple, Bedford Avenue and Bergen Street occupies the former Loew’s Bedford Theatre, but it was a house of worship as long ago as 1951, when it was organized as Bethel Temple, and renamed in 1954 for Bishop Douglas Washington, pastor from 1951-1988. Fanny Brice is said to have launched her showbiz career at the Bedford in 1906.

Unity Club

The Union League Club of Brooklyn, facing the equestrian Grant portrait, boasts a figure of Grant of its own above the front entrance arches along with Lincoln. Much like Park Slope’s ornate Montauk Club (on Lincoln Place and 8th Avenue no less) this was built to house a private club, of which there were many in Brooklyn in the late 1800s. The Union League dates to 1863 and was formed by adherents to the Union cause in the Civil War (and the NYC area supported the South by and large in that period). Club members paid for the Grant statue outside the front door.

The club was completed in 1890 by the firm Lauritzen & Voss. Originally there were bowling alleys and shooting ranges in the basement, and billiards, gym, library and dining rooms. It is now a senior citizens center. The ‘Unity Club’ inscription is apparently an error.

The former Hotel Chatelaine occupies the west side of Bedford Avenue between Dean and Pacific Streets. As early as 1930 it became the Swedish Hospital and today it contains rental units.

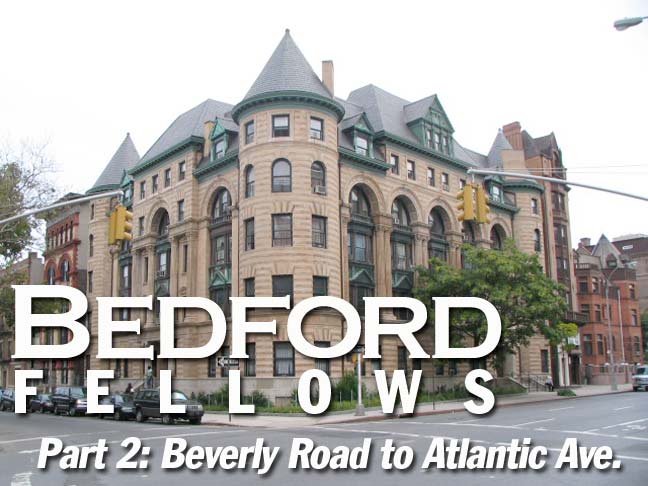

The Imperial Apartments, SE corner Bedford Avenue and Pacific Street, was designed by architect Montrose Morris for developer Louis Seitz. When completed in 1892 it had the largest apartments by square foot in the city of Brooklyn; they were subdivided long ago. Until it was revived by its present owner the building was empty and boarded up for a number of years.

Francis Morrone in An Architectural Guidebook to Brooklyn: This is the building that for me most clearly defines the Grant Square neighborhood. It bespeaks the values of Brooklyn’s bourgeois interlude, exuding a sense of solidity and longevity that proved rather chimerical, as so often is the case, not only in Brooklyn but in America, In Paris or vienna or Bucharest a building such as this might have apartments rented — not owned — by the same families over several generations.

Armory #2

Sad to say but the magnificent 23rd Regiment Armory, filling the block between Bedford Avenue, Franklin Avenue, Pacific Street and Atlantic Avenue, is used as only a men’s homeless shelter these days. It was built from 1891-1895 by the firm Fowler and Hough with an assist from Isaac Perry. It has perhaps the grandest corner tower in Brooklyn, and one of the tallest at 136 feet in height.

The 23rd Regiment was established at the outbreak of the Civil War and was housed in the old Clermont Avenue armory in Fort Greene from 1873-1895, when it moved into this vast new building. Nancy Todd reports: The once lavish interior appointments, inclusing the WPA-era officers’ lounge, have been nearly lost dur to deterioration, vandalism and alteration.

Since the mid-1830s the Long Island rail Road has been a fixture on Atlantic Avenue, as trains have run by horsecar, then steam and electric power. The LIRR runs in a tunnel from Flatbush to Bedford Avenues, ascends to an el from Nostrand to Howard Avenues, descends into a tunnel again, rising to daylight for good just west of Jamaica station. Here we see the brief open cut just east of Bedford and the Nostrand Avenue elevated station.

Bedford Avenue Part 3: Atlantic Avenue north to Manhattan Avenue

2 comments

[…] Calendars Two Brooklyn Buildings [Brownstoner] Photo via Forgotten NY Monthly […]

[…] Calendars Two Brooklyn Buildings [Brownstoner] Photo via Forgotten NY input, textarea{} #authorarea{ padding-left: 8px; margin:10px 0; width: 635px; } #authorarea h3{ […]

Comments are closed.