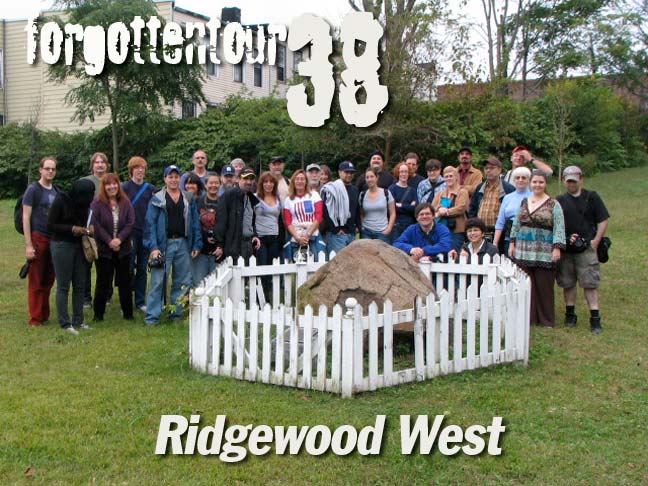

So, what were 32 ForgottenFans doing gathered around a fenced rock in soggy Ridgewood on an October 2009 Saturday? They were standing alongside the marker that divided the ancient towns of Bushwick and Newtown, or so the story goes.

In the first (to my recollection) ForgottenTour that spanned two boroughs, Forgotteners gathered at the Jefferson Street station on the BMT L Canarsie line, which was actually running uninterrupted from Manhattan across the river to Brooklyn. The L runs through three boroughs, but does not have a stop in Queens to call its own (though the Halsey Street station is on Wyckoff Avenue, which is on the borderline. The weather? Well, it started out partly cloudy but as has been the tradition for ForgottenTours the last few years, rain quickly overspread, making the last leg of the tour fairly soggy. Intrepid Forgotteners soldiered on, however. WAYFARING MAP: TOUR 38

We first noted the new Type G telephone pole fixtures on Wyckoff Avenue, itself the subject of a Forgotten feature in 2008. The Jefferson Street station is unusual in that the entrance is through a surface brick structure (the line was constructed in 1928).

The Canarsie Line was the last line fully employing mosaics for station signage and decoration — in fact the simpler, Machine Age design scheme was already being drawn up for new IND stations along 6th and 8th Avenues that would open during the following decade. Designs like this required a lot of hand cutting and meticulous work, and station design would vastly simplify in the years following.

Flushing Avenue was once a toll road known as the Brooklyn-Newtown Turnpike (graded in 1809 along a winding colonial route). Further east, it connected with the North Hempstead Turnpike which crossed the southern Flushing Meadows into eastern Queens. As this photo from the 1930s demonstrates, the road was once lined with farmhouses from the Dutch and British colonial eras, built from the late 1700s to the early 1800s. As we’ll see only one of these houses stands today.

Flushing Avenue was once a toll road known as the Brooklyn-Newtown Turnpike (graded in 1809 along a winding colonial route). Further east, it connected with the North Hempstead Turnpike which crossed the southern Flushing Meadows into eastern Queens. As this photo from the 1930s demonstrates, the road was once lined with farmhouses from the Dutch and British colonial eras, built from the late 1700s to the early 1800s. As we’ll see only one of these houses stands today.

Covert farmhouse, (formerly) 1410 Flushing Avenue. An old name for Seneca Avenue was Covert Avenue. Hubb farmhouse, 52-15 Flushing Avenue. This house once stood just east of Metropolitan Avenue. Woodward farmhouse, 18-91 Flushing Avenue, demolished 1938. Nearby Wyckoff farmhand house. This is also seen in the foreground of the Flushing Avenue panorama above.

Two views of the Onderdonk-Van Der Ende House, 18-20 Flushing Avenue, in the 1930s. The Onderdonk House is the lone survivor of what was once many colonial farmhouses along this stretch of Flushing Avenue.

While the Onderdonk-Van Der Ende House isn’t the oldest colonial house in NYC (the honor goes to the Peter Claesen Wyckoff House in East Flatbush, first built in 1652) it’s the oldest Dutch Colonial stone house. There has been a structure in this site, at Flushing and Onderdonk Avenues, since 1660 when Hendrick Barents Smidt built a small dwelling here. Paulus Van Der Ende of Flatbush had purchased Smidt’s farm ( a total of 58 acres — most of what is now Ridgewood) and began constructing the present building in 1709. Van Der Ende, in turn, sold the property to Adrian Onderdonk in 1821, who built the house as we know it today with a gambrel roof, Dutch doors divided in half, and a central hallway with rooms on each side.

The house passed through many owners after the Onderdonks sold in the early 20th Century. When Louise Gmelin purchased the house in 1908, along with 1.5 acres (about the limit of the present property) she operated a livery stable on the property and dealt in scrap glass — there were many glass factories and breweries in the area. The Onderdonk House has also been a speakeasy, livery stable, greenhouse manufacturer, and fascinatingly, a factory for spare parts for the Apollo space program.

The Greater Ridgewood Historical Society entered the picture in the late 1970s and largely rebuilt the house after a devastating fire. The house opened to the public in 1982 as a historic site. It has been home to tours, historic exhibits of Dutch colonial history, and has even hosted weddings in the decades since. This house was the centerpiece of ForgottenTour 38.

ForgottenFans were impressed with the Onderdonk House — it’s a surprise to see it along Flushing Avenue. While much of Ridgewood is pleasantly residential, Flushing Avenue is lined with machine shops, scrap metal purveyors and factories.

The Onderdonk House, celebrating its tricentennial, has a roof much in need of repair. The Queens Tribune, October 8, 2009:

Unfortunately, this 300-year-old Ridgewood relic’s ability to survive is being threatened by a badly-decaying roof in desperate need of repair. In the house’s attic, a room which formerly served as a meeting space for class visits or colonial dinners, natural light streams in through dozens of gaps and cracks speckled across the ceiling. The space has been out of commission for the past few years; during rainstorms water seeps into the room.

The house’s librarian and archivist George Miller said the roof, which was constructed with cedar shingles after a fire in the late 1970s, is in dire need of renovations.

Curator Richard Asbell said the problem with the roof has gotten progressively worse in recent years. He said he dreads the upcoming winter and fears the structure will not make it if the season is particularly harsh.

Fortunately, a number of community leaders and local businesses have joined forces to come to the houses rescue by creating “Let’s Raise the Roof at the Vander Ende-Onderdonk House,” an event geared towards raising proceeds to be donated to repairing the house’s rotting roof. On Oct. 23, [2009], there will be a cocktail reception complete with catered food, live music, a bonfire and party favors. Mayor Mike Bloomberg will also be in attendance and recognized as a special guest.

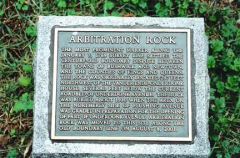

The Rock

In the back yard of the Onderdonk House is a large rock surrounded by a picket fence. It is the official position of the Gtreater Ridgewood Historical Society that this is the hsitoric “Arbitration Rock” used to delineate the border, along the Brooklyn-Newtown Turnpike, of the borders of the towns of Bushwick and Newtown, or today’s Brooklyn-Queens line. In 1769 a large stone was used by surveyor Peter Marschalk to designate the boundary, which had been in dispute. The story goes that the rock had been left underground when Onderdonk Avenue was extended in 1930, and when the avenue was re-graded in 2000 the rock was exposed. It was moved to the backyard of the Onderdonk House the following year. The GRHS has yet to provide documentation in proof.

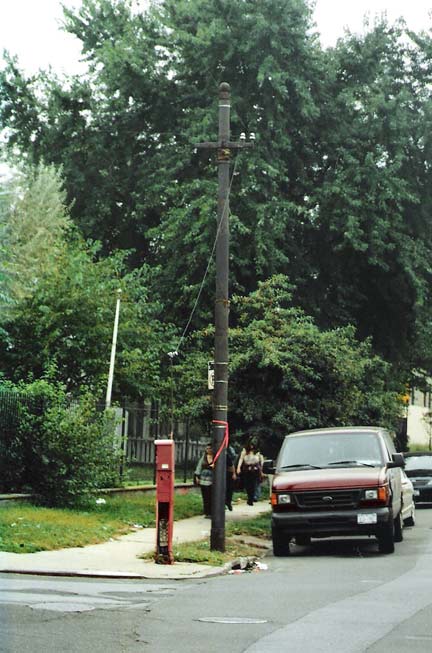

A lone trolley pole at the corner of Flushing and Onderdonk ia remnant of the era when trolleys plied this stretch of Flushing Avenue.

Venerable Queens historian Vincent Seyfried in Brooklyn Rapid Trolley Lines in Queens:

On July 1, 1889 the Brooklyn City R.R. had secured from the Common Council of the City of Brooklyn permission to extend their tracks from the old terminal at Graham Ave. to the Bushwick Railroad’s tracks at Bushwick Avenue, and from Knickerbocker Avenue to the city line (Onderdonk Ave. ) these two grants of 1889 thus covered all the gaps in the proposed continuous route into Queens County…

Trolleys, in the beginning, were horsecar lines. Electrification began in the early 1890s. Brooklyn Rapid Transit, later the BMT, ran the Flushing Avenue trolley until 11/28/48 as #57. The Flushing Avenue bus that replaced it still carries that number.

And so, you can notice one object along a busy street — unnoticed by most – that’s a remnant of an entire chapter in transportation history.

Regarding The Rock, Bob Singleton of the GAHS says:

In the back yard of the Onderdonk House is a large rock surrounded by a picket fence. It is the official position of the Greater Ridgewood Historical Society that this is the historic “Arbitration Rock” used to delineate the border, along the Brooklyn-Newtown Turnpike, of the borders of the towns of Bushwick and Newtown, or today’s Brooklyn-Queens line.

In 1769 a large stone was used by surveyor Peter Marschalk to designate the boundary, which had been in dispute.

The rock disappeared by the mid-1800s and phoenix-like it (or something like it) reappeared a few decades later.

The story goes that the rock again vanished from sight and was buried under landfill when Onderdonk Avenue was extended in 1930

Stanley Cogan of Queens Historical Society prevailed upon the borough president to fund a “fishing”expedition, and DEP with a backhoe found a rock buried under the street in 2000.

Rumor claims that it split when they tried to move it to Onderdonk House.

Bob Singleton, past President of the Greater Astoria Historical Society, whose family lived in Maspeth Kills in the seventeenth century, is intrigued by the purported discovery. “The rock’s location is pinpointed by records to a specific spot on the ground.”

He is looking forward to GRHS backing up their claims with the professional archeological field report (that will document through drawings and photographs the rockís location and discover) “Any such report”, he states, “will dispel any controversy on its ‘discovery’ by GRHS.”

However, after nearly a decade such a report has yet to be released to the public.

Until that happens, Singleton suggests that a large rock at Varick Avenue and Randolph Street (above), a couple of blocks away in Brooklyn, should be the focus of the public’s attention.

“If authentic, it’s nearly 100 years older than Arbitration Rock, and designates the original 17th century border between Brooklyn and Queens.” Since another similar marker older than Arbitration Rock disappeared recently (on Morgan Avenue and Rock Street), he suggests it should be protected by Landmark Designation and calls upon GRHS, NHS, and GAHS to work together to protect it.

LEFT: the King of All Buildings seen from Onderdonk Avenue. RIGHT: handpainted sign, Flushing Avenue.

Our second stop was at a warehouse on Flushing and Metropolitan Avenues. Note the chimney still marked “Bohack” — the well-known NYC supermarket chain closed well over 30 years ago. German immigrant Henry C. Bohack opened his first grocery in 1887 and over the years Bohack’s developed into one of the first powerhouse grocery store chains. Grand Union, Key Food and all the rest were to follow. When the Depression arrived in late 1929, Bohack responded by actually opening more stores to provide employment. The founder passed away in 1930.

Bohack was recognizable by the distinctive “B” in the logo. A building now used as a warehouse in the triangle formed by Flushing Avenue and Troutman Street still has those B’s emblazoned on the sides of the building. As this photo from the 1930s demonstrates, this building once housed a Bohack’s restaurant.

Bohacks prospered until 1974 when the chain went bankrupt. After an attempted merger with Shoprite failed, Bohacks disappeared into the history books in 1977. Occasionally, though, an old awning or sign is taken down and the Big B is in evidence briefly once more.

There are actually two Linden Hill Cemeteries between Woodward, Grandview and Metropolitan Avenues and Starr and Stanhope Streets: Linden Hill Methodist, accessible from Woodward Avenue and Hart Street, and Linden Hill Jewish, on Metropolitan Avenue east of Starr Street. The Jewish cemetery is the final resting place of longtime NYS Senator Jacob Javits (1904-1986), while a notable permanent occupant of the Methodist cemetery is playwright and Broadway producerDavid Belasco (1853-1931).

In a process known as ‘enameling,’ photographs of the deceased are burned into porcelain (in a process described in detail in John Yang’s book, “Mount Zion: Sepulchral Photographs.”) This was a custom brought to the USA by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. Many more of these examples can be found in nearby Calvary and Mount Zion Cemeteries.

Stockholm Street

Stockholm Street runs from Bushwick Avenue northeast to Woodward Avenue, facing Linden Hill Cemetery, but only one block is landmarked: its last, between Onderdonk and Woodward, is one of those streets that NYC aficionados know about but the guidebooks and tour buses have so far managed to avoid. (It might be better that just the NYC cognoscenti (and ForgottenFans) are aware of the beautiful block, lined with porched, bowed attached houses and paved by a literal yellow brick road.) It was not named for a preponderance of Swedes in the neighborhood (though Bay Ridge, a few miles away, spent most of the 20th Century populated by Scandinavians in the majority) but for the Stockholm brothers, Andrew and Abraham, who provided land on Bushwick Avenue for the Second Dutch Reformed Church of South Bushwick (qv. this page) in the 1850s.

According to the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission report on the Stockholm Street designation, the distinctive buildings were developed by Joseph Weiss and Louis Berger beginning in October 1908. The first of four groups of curved bayed, limestone ornamented, wood porched homes was constructed that year and the entire street was completed two years later. German immigrant Berger built 5,000 homes in Ridgewood and Bushwick alone between 1895 and 1930. By 1910 he had moved his offices to Ridgewood, joining developers August Bauer and Paul Stier.

Note the distinctive yellow color of the bricks. They were fired in kilns developed by Balthazar Kreischer, another German immigrant. By 1910 the Kreischer operation was owned by Peter Androvette. Both Kreischer and Androvette’s names can be found on Staten Island street signs in the small company town, Kreischerville, built by Kreischer during his years manufacturing brick.

One of Kreischer’s specialties was smokestack bricks, which were molded into trapezoidal shapes that produced circular stacks when laid side by side. This type of brick was used creatively in Ridgewood to create the curved bays that characterize many of its rows, including those in the Stockholm Street Historic District. Most of the Kreischer brick used in Ridgewood, including the Stockholm Street Historic District, is iron-speckled brick with smooth surfaces, laid with tight, flush joints. Also called iron-spot bricks, they were produced by adding manganese in a finely granular form. Rock-faced brick, also manufactured by Kreischer, was used in Ridgewood for details such as bandcourses and lintels.

If anything, a rainy day makes the distinctive yellow paving stones of Stockholm Street stand out all the more. Though there are a few remaining red-bricked streets in Jamaica, this is the one and only street paved with this yellowish-brown hue. It was completely restored around 2000 after the originals had fallen into disrepair. The original bricked street, and the neighboring bricked streets now paved over with asphalt, were produced by the clay manufacturer SBT Company of Clearfield, PA.

Stockholm Street is a longtime FNY touchstone and was the subject of a ForgottenSlice on a somewhat better day, weatherwise.

The twin towers of St. Aloysius Church (see above photo) anchor Stockholm Street and its church bells ring out to signal vespers and matins throughout the day. It is the tallest building in NYC constructed with Kreischer brick, completed in 1917 by architect Francis Berlenbach. Photographer Bob Mulero here details the intricate woodwork on the church door and the beautiful ironwork of the lampposts on the church steps.

By now the rain was drenching, as it would continue to do the rest of the day, but the tour soldiered on a few more blocks to Ridgewood’s newly minted landmarked district as designated by the LPC, along Gates, Fairview, Grandview and Forest Avenues, as well as Palmetto and Woodbine Streets. Most were built by the prolific developer Gustave Xavier Mathews Company, which also built in Astoria, Long Island City and Maspeth. With that, after a diner meal and an el ride home, FNY Tour 38 was in the books.

LARRY STELLER FLICKR PAGE: RIDGEWOOD

Photos: Bob Mulero, Tim Skoldberg, Mitch Waxman