On the first three Saturdays in August the Department of Transportation shuts down Lafayette Street, 4th Avenue, Park Avenue South, Park Avenue and part of West 72nd Street in the Summer Streets program, designed to give New Yorkers the run of these streets without threat of auto traffic. It’s been a smashing success after its 2009 institution, though the program is geared toward bicyclists and runners; plodding pedestrians like your webmaster are still largely relegated to the sidewalk, mostly by necessity. On August 7, 2010 I decided to walk the route and give the event a ForgottenNY spin.

Pretty much the highlight of the Summer Streets project for me was the opportunity to walk the Park Avenue Viaduct, which opened in two pieces from East 40th to East 46th Streets in 1919 and 1928 surrounding Grand Central Terminal and later the Metropolitan Life (formerly Pan Am) Building . It has always been designed expressly for auto traffic and doesn’t have shoulders or sidewalks of any sort — hence its oddities, architecture and statuary are largely mysteries to all but the pedal to the metal motorists and cabbies who speed past them every day.

The Viaduct’s original streetlamps, or at least some of them, are still in place on the ramp between East 40th and East 42nd Streets. Grand Central Terminal was completed in 1913 (replacing an earlier depot) and belongs firmly in the Beaux-Arts tradition, and when the ramp was first proposed, its architecture was meant to echo the great building it surrounded. The viaduct also has decorative railings with a sea shell motif. (Compare the Brooklyn Bridge walkway lamps — they look like the originals but are actually copies from the early 1980s.)

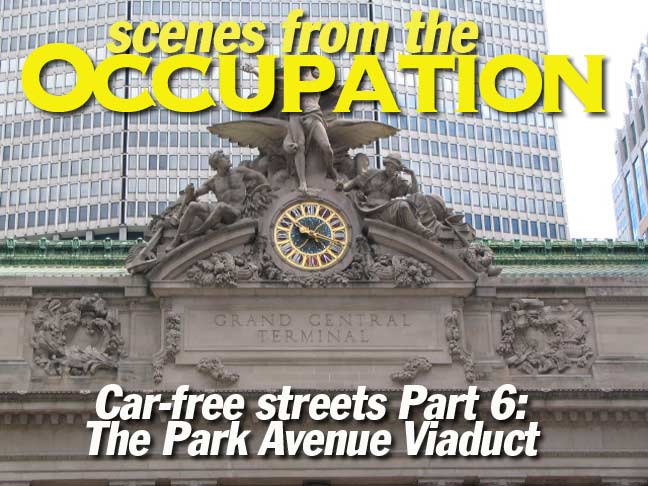

Travel outside the building to see the sculpture “Transportation” by French artist Jules-Alexis Coutan that sits atop Grand Central Terminal. You will see Mercury flanked by Minerva and Hercules. Minerva is the goddess of wisdom and represents all the thought and planning put into this building. Mercury is the god of speed and represents both the speed of commerce as it grew up into midtown Manhattan from the financial district and, of course, the speed of trains. The mythological hero, Hercules, represents the strength of the men who built Grand Central. Carved out of Indiana limestone, the group stands 50 feet high and 60 feet wide, weighs 1,500 tons, and surmounts a clock 13 feet in diameter. Grand Central Terminal

Views of East 42nd Street from the viaduct

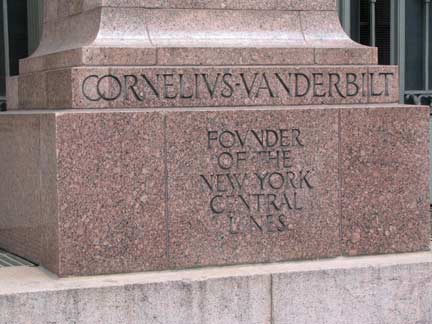

Ironically, this statue of Cornelius Vanderbilt stands athwart the one mode of transportation that he had nothing to do with — auto traffic. Normally viewable only from afar by lowly pedestrians, the statue stands at the head of the Park Avenue Viaduct where the roadway splits in two. It’s actually one of the oldest statues in Manhattan, having been sculpted in 1869 by Ernst Plassman and originally placed downtown at the Hudson River Freight Depot (now largely replaced by the Holland Tunnel entrance). The statue was moved to the south facade of Grand Central Terminal at its 1913 opening.

The majestic eagle perched on the Viaduct at East 42nd Street and vandebilt Avenue is actually a relic from the previous Grand Central Terminal, which stood here from 1898-1910. The eagles numbered 10 or 11 (accounts differ). This eagle was discovered at the Capuchin Theological Seminary in Garrison, NY.

Over the years, two sleuths in particular have pursued the other eagles from the original Grand Central. David McLaine of the NY Daily News did the first such survey in 1966 and found one in Sleepy Hollow, NY (then North Tarrytown), two at the Vanderbilt Museum in Centerport, Long Island (pictured below right; photo: E.E. Weaver), two in Mount Vernon, NY, and one in the Capuchin Theological Seminary in Garrison, NY. Meanwhile, Long Island Rail Road branch manager and historian David Morrison found another in a Sussex, NJ farm. Morrison, along with the owners of a Bronxville, NY house, waged a successful campaign to have their eagle placed at Grand Central; it’s now situated over the Lexington Avenue GCT entrance.

Dave Morrison, in a correspondence with FNY: In my opinion, the Garrison eagle doesn’t belong there. It is a redundancy and it detracts from the historic view of Grand Central Terminal. When one walks east on 42nd Street approaching Grand Central Terminal, the first thing seen is that eagle with the Terminal in the background. This is not the view that Jacqueline Kennedy enjoyed when she fought so hard to have Grand Central Terminal saved.

Penn Station, of course, had its own set of eagles.

Seeing things from a new perspective on my first walk on the Park Avenue Viaduct. Come to think of it, even in cabs, I must have come this way only once or twice, and I don’t remember it at all. I chose the west roadway past the west end of GCT and the Metropolitan Life (Pan Am) Buildings. The Pan Am Building has a helicopter landing pad until 1977, when an accident killed 4 passengers and a pedestrian on the ground. LEFT: Looking down on East 45th; the lamppost belongs to Vanderbilt Avenue.

ForgottenFan Eric Weaver: The scallop shell motif on the railings around Grand Central was favored by William K. Vanderbilt II. They are everywhere around his estate in Centerport.

The Viaduct tunnels through the 1929 Warren and Wetmore New York Central Building, since renamed the Helmsley Building by its then-owner, “Queen of Mean” Leona Helmsley, in honor of her husband, Harry, the former owner of the Empire State Building. The current owner is Goldman Sachs, which purchased it for over $1 billion in the go-go real estate market of 2007.

The NY Central, formerly the railroad that connected NYC with surrounding states, is now the commuter railway Metro-North.

The tunnel through the Helmsley Building has its own distinctive wall lamp stanchions. These probably once held globe-shaped luminaires.

The Helmsley Building and its clock anchor the north end of Park Avenue north of Grand Central, and its statuary and clock are echoic of the “Transportation” sculpture that face East 42nd street. The sculpture and clock are the work of sculptor Edward Francis McCartan:

Cut in limestone, the clock features two statues four times life size. The male figure on the left is Transportation. Transportation, who symbolizes the spirit of speed, rests his arm on a winged wheel of Progress and holds the staff of Mercury. On the right is a female figure, Industry, who embraces a staff in her arm, while resting on a beehive. Several other smaller symbolic figures round out the design including the Liberty Cap, crowning the clock’s top. The clock, 45 feet in width and 19 feet high , has a dial which spans 9 feet in diameter.

Normally, reclining on a beehive while nude is not recommended.

We’ve seen a rare bird. Here’s a rare stoplight. The pair here at Park Avenue, East 46th Street, and the Viaduct are two of three extant stoplights of this particular species. Corvington-esque long-armed stoplights, with a wheel motif in the scrollwork, first appeared in 1924 and spread like wildfire in NYC’s built-up areas. Beginning in the late 1950s they began to be supplanted by the thick-shafted, guy wired models that still are in power, and these posts died out.

Page completed August 26, 2010

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | PART 7