Visiting Staten Island, of course, is a provocative act.

I’ll paraphrase the opening line to my introduction to the ForgottenBook and say that if you’re a New Yorker not from Staten Island, you’re not supposed to visit Staten Island, you’re not supposed to care what goes on there at all, you’re committing a subversive act and if it gets around you’ve been there — they’ll come and revoke your rights to remain in Manhattan, Bronx, Brooklyn or Queens (they know what you’ve been doing because your handheld device records all). After all, the island is full of rednecks, paintball players, so-called ‘goombahs’ and, gasp, Republicans. If you’re a real New Yorker, you’re not supposed to ride the ferry or, if you’ve been shanghai’ed aboard by out of town relations, you’re supposed to enjoy the ferry ride then shuffle around to the waiting room to pick up the next boat.

As most readers here or on the Kevin Walsh facebook page know, I’m hardly a typical New Yorker. I say I’m in line, I pronounce the R’s at the ends of words, I don’t walk at a break neck pace, and I don’t drink coffee at all, so there’s no bother with ordering it ‘regular’ or not for me. and I can be seen prowling around Staten Island fairly regularly, just about every location on the island. I have a Verizon LG flip phone, mostly used for emergencies, so the NSA doesn’t know where I am!

I’ve been to Rossville many times. Under its placid veneer of suburbanity, there’s over 300 years of history. The British arrived as early as 1684 and in the early days the area was called Smoking Point and later, Blazing Star, for a long-lost tavern (a separate Staten Island locale was called Bull’s Head, after another such tavern).

By the 1830s the southwest Staten Island area was named for a local wealthy landowner, William Ross (who built a replica of Windsor Castle near the Blazing Star tavern), the small town was known before the Revolution by the picturesque name Blazing Star. Ferries, and later steamships whose wrecks are still sinking in the Arthur Kill, connected it with New Jersey. After the West Shore Expressway was built in the 1970s, it spurred development south of the highway, with street after street filled with what songwriter Malvina Reynolds and folksinger Pete Seeger would call “little boxes made of ticky tacky that all look just the same.” North of the expressway are shipwrecks, auto repair shops, abandoned cemeteries, and assorted detritus that has been there for decades and may last decades more. Today Rossville is fairly compact and can be defined by the Arthur Kill waterway, the West Shore Expressway, the South Shore Golf Course and Woodrow Road.

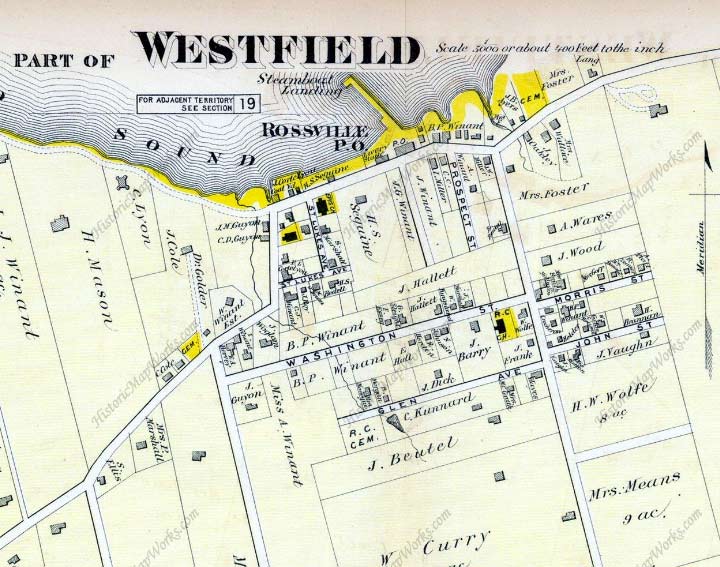

This 1873 atlas plate shows the Rossville street plan as it existed, more or less, until the mid-1970s. The vertical line at the right is Rossville Avenue, then called Shea’s Lane; the two vertical lines at left are Bloomingdale Road and Winant Avenue, respectively. In 1873 neither had a name, and neither does Arthur Kill Road. In fact only two street on the 1873 map has kept their old names: Morris Street and tiny St. Lukes Avenue.

A couple of things happened by the mid-1970s that pulled Rossville Avenue from near-rurality: a devastating 1973 brush fire burned down many local residences, and the 1976 opening of the West Shore Expressway which prompted local farmers to sell suddenly profitable land to local developers, who over the next few decades built the tract houses that gave Rossville the look it has today. But pockets of the old days are still there…

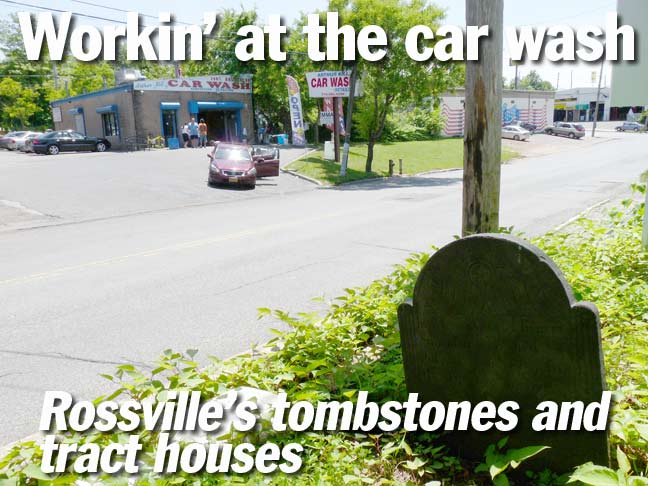

The S74 bus lets you out here, at Arthur Kill Road and Rossville Avenue. One of the neighborhood’s few surviving older homes is here, behind the red car. Behind the treeline at right are two reminders of the recent past and also the truly ancient past.

Behind the trees, Arthur Kill Road makes one of its closest approaches to its titular body of water. The Blazing Star Ferry ran from here to Woodbridge, New Jersey and steamboats still docked here at the time the atlas plate was produced in 1873. I have been coming here since the late 1990s to gaze at the collection of rotting, corroding wrecks found here, as have some daredevils such as Nick Childers and Shaun O’Boyle.

On August 22, 1777 in the midst of the American Revolution, General John Sullivan directed about 1000 continental soldiers under his command to cross at the Old Blazing Star Ferry to New Jersey as the British army punctuated their departure off the island with cannonade. Historians and history buffs with a penchant for the American Revolution characteristically describe Sullivan’s raid of Staten Island as a minor skirmish. But to understand an event like the American Revolution it is not enough to analyze major battles (that is for military enthusiasts). The revolution was about the struggle among people. The battle of Staten Island was primarily a battle of Americans (Patriots) against Americans (British Loyalists). The revolution was a civil war as much as it was a revolutionary war and no study makes a better case for this as does the study of revolutionary war Staten Island. Moreover, as Sullivan escaped across the Arthur Kill tidal strait to New Jersey he carried with him papers that were discovered among the plunder. The seditious papers (most likely forgeries) implicated the Quakers – staunch pacifists refusing to take sides in the conflict – as potential enemies of the glorious cause of American independence. As a result, the Continental Congress ordered the arrest and exile of the Quaker leaders to Virginia. 16 Although they were released well before the war’s end, this action set a precedent for how America reacts toward specific groups on American soil during a time of war. This reaction was witnessed again with the internment of Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants during WW II and more recently, in response to the September 11 terrorist attacks, with the “Special Registration” of visiting nationals of Afghanistan, Iraq, and other Arab countries. Gotham Center

Founded in the 1950s by Arthur Witte Jr., the yard sits on a desolate stretch of land at the junction of Arthur Kill Road and Rossville Avenue. Once described by the New York Times as an accidental marine museum,” the Witte Marine Scrap Yard accumulated far more vessels than it could dismember, and the boats quickly piled up. Arthur Witte intentionally stored the vast collection of ships for parts, but the wrecks became a habitat to teeming colonies of underwater fauna. A change in environmental law mandated that these eco-systems be untouched and the hulks endured. Over 400 ships inhabit the yard, now known as the Don John Iron and Metal Scrap Processing Facility.

The junkyard is home to one of the largest collections of historic boats in the United States and has attracted a deluge of maritime historians from across the country. Some of these craft have tales as gripping as the metropolis of Manhattan itself. The Free Library

Vessels from all decades of the 20th Century lie in a state of decomposition and rust at this scrapyard at Arthur Kill Road and Rossville Avenue. Most are tugs or cargo ships. The former piers have collapsed and are for the most part unpassable; these wrecks are officially located in the Witte Scrapyard and are off limits to the public, which hasn’t stopped dozens if not hundreds of urban explorers and gawkers from wandering out to these hulks and snapping away.

Since Mr. Witte’s passing in 1980 his descendants have been slowly dismantling the boatyard, known by some locals as “the boneyard.” Among the ships “interred” at Witte was the fireboat Abram S. Hewitt, which aided in rescuing survivors of the General Slocum steamboat disaster in 1904, the US Navy submarine hunter PC-1264, ‘one of only two U.S. Navy ships to have a predominately African-American enlisted complement during the war,’ and the tug YOG-64, which still remains.

More photos at Flesh and Relics.

I have often called Pelham Cemetery in City Island, Bronx, New York’s only waterside cemetery, but after thinking it over, I’ll have to amend that to include the Blazing Star Burying Ground (aka Sleight Homestead Graveyard) on Arthur Kill Road east of Rossville Avenue. It was founded before 1751, as that is the date on its oldest gravestone. The stones bear names familiar to Staten Island residents aware of the names on its street map: Sleight, Seguine, LaForge, Poillon. The last burial was in 1865 for John G. Shea, of the same family Shea’s Lane, now Rossville Avenue, commemorated. (One prominent road from this style of nomenclature in Staten Island remains: Gifford’s Lane in Great Kills.)

According to Find A Grave, the Seguine family has the most family members buried here, with 11 of the surviving 46 gravesites. Here I have grouped the prominent sandstone markers, which although some of the oldest stones in the cemetery, still remain throughly legible: though sandstone can and does decay, the marble and limestone markers the followed sandstone in the 19th Century are much more subject to the predations of wind, pollution and rain. Israel Oakley (1739-1824), whose gravestone is the largest in the cemetery, was the great-great-grandfather of Staten Island historian William T. Davis, an entomologist by trade who wrote several Staten Island histories and guidebooks. He co-founded the Staten Island Institute of Arts & Sciences.

Two limestone markers, both members of the Seguine family.

There’s no sidewalk on the north side of Arthur Kill Road here, so the only passersby on the graveyard site here are motorists, most of whom speed by so quickly the completely miss the cemetery, here for 260 years at least. Hiteita Simonson’s (1722-1789) marker has been by the side of the road here since the year of George Washington’s inauguration. Of course Arthur Kill Road is likely an amalgamation of several roads along the Arthur Kill strait. It’s fascinating that such an ancient relic is within plain sight of the car wash, gym and succession of eateries along the south side of the road.

The late Bernard Ente got the best shots of the cemetery I have seen. I put them on this page.

Second Empire house dating to the 1880s at least, across the road from the cemetery. Until recently it was home to the Lava Lounge.

Moving west along Arthur Kill Road are a couple of relics of indeterminate age. The park bench once assisted passengers of the S74 bus, which until the 1970s ran directly along Arthur Kill Road. Since then the bus stop has been moved to Rossville Avenue and the West Shore Expressway; the bus now serves the residential neighborhood that sprung up after the expressway was built.

Crazy Goat, formerly C&G Feeds, is located in an ancient wood building that was once home to a volunteer fire department. The store was founded on Sharrotts Road in Charleston, down the road a piece, and was formerly owned by a fellow with the same name as screen star Clark Gable.

Desolate stretch along Arthur Kill Road west of Rossville Avenue.

Arthur Kill Road at St. Lukes Avenue, looking toward one of the two liquid natural gas tanks placed at Arthur Kill and Bloomingdale Roads. The tanks were outmoded almost as soon as they were built and were never filled, and have been left to sit and rust since. Staten Island, folks!

St. Lukes Avenue is one of the oldest routes in Rossville. It runs one block from Arthur Kill Road to Veterans Road North, a service road of the West Shore Expressway. It’s an odd place for a bed and breakfast, but the Wedding Cottage is part of the region’s history. In 1844 St. Luke’s Church was founded in Rossville by several trustees of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Richmondtown, among them William E. Ross. The new church was designed by famed Staten Island painter Jasper Cropsey. The attendant cemetery (see below) was also founded at this time, incorporating two older and smaller cemeteries belonging to the Woglom and Vaughn family cemeteries, where the older grave markers are found.

Though St. Luke’s Church was consolidated with St. Stephen’s Church in Tottenville in 1945 and Rossville became a veritable Staten Island ghost town until the 1970s, two church buildings on the old property was still there, the parsonage, restored by the nearby Old Bermuda Inn as a bed and breakfast …

… and another St. Lukes’ church building is now Big Nose Kate’s Saloon, on a bend of Arthur Kill Road between St. Lukes Avenue and Hervey Street. Named on WCBS-TV’s list of best biker bars in NYC, the saloon is named for a perhaps better-known venue in Tombstone, AZ; both commemorate Mary Katherine Horony Cummings (1850-1940), the companion of John Henry “Doc” Holliday, dentist and participant in the famed Gunfight at the OK Corral. Big Nose Kate’s ghost supposedly haunts the Arizona saloon.

‘In an 1896 article Wyatt Earp said that “Doc was a dentist, not a lawman or an assassin, whom necessity had made a gambler; a gentleman whom disease had made a frontier vagabond; a philosopher whom life had made a caustic wit; a long lean, ash-blond fellow nearly dead with consumption, and at the same time the most skillful gambler and the nerviest, speediest, deadliest man with a six-gun that I ever knew.”‘ ––wikipedia

The sprawling Old Bermuda Inn was originally constructed in 1832 (The New York AIA Guide reports 1855) by the Mersereau family. The older part of the expanse is at Arthur Kill Road and Hervey Street, but the original restaurant has greatly expanded and built in recent years as it was converted to a wedding caterer and event space.

Yet one more historic home in the area, at the southeast corner of Arthur Kill Road and Hervey Street, reportedly dates back to 1840.

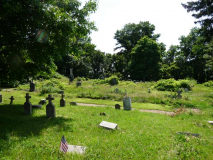

Another tangible remnant of St. Luke’s Church is its attendant cemetery, established in 1844 between Zebra Place (old Winant Avenue) and Bloomingdale Road. In 1874 the church began selling gravesites to the public and thus, it has always been nonsectarian and nonsegregated. St. Luke’s was absorbed into St. Stephen’s in Tottenville; was early as 1920, St. Luke’s was losing parishioners, as by them the steamboat landing and local post office had closed, the mansions were becoming dilapidated and the stench from the factories in Carteret, NJ across the Arthur Kill were becoming overwhelming. Today, though, the cemetery is well-maintained and kept neat by the diocese of the Episcopal, or Anglican, church of New York.

As mentioned earlier, two smaller and older cemeteries, the Woglom and Vaughn family burial grounds, were incorporated into St. Luke’s Cemetery when it was founded in 1844. Today the delineations between the cemeteries are indistinct, but several very old stones give a general idea where they were. Unlike Blazing Star, many of these markers are unreadable unless you want to spend time clearing the moss.

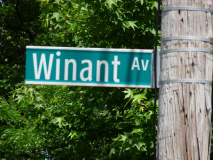

Gravestones and street signs preserve Staten Island history. The Winant, or Winants, family was prominent in Staten Island in the colonial era, and Winant Avenue is a major north-south route.

When the West Shore Expressway was built in the mid-1970s the northern end of Winant Avenue at Arthur Kill Road was separated from the southern part. Soon after, the cut-off section was renamed Zebra Place. I suspect that somewhere, a city planner left it up to his kid what this short street should be renamed, and the child chose his or her favorite animal.

Another example, Kunath, in the cemetery and on the street.

St. Luke’s is a “living” cemetery, still accepting interments, now numbering over 800.

St. Luke’s Cemetery, overlooking Arthur Kill Road and Mollie Ryan’s Pub

West of the cemetery on Arthur Kill Road, another used car dealer/barbershop combo.

There are a couple of dead-end stubs in the area named Westfield Avenue. Just another ho-hum local street name? This one, along with other street names scattered around the island, hark back to Staten Island history as well.

Just as Kings County numbered six different ‘towns’ before the City of Brooklyn absorbed them all and then consolidated as Greater New York in 1898, Staten Island was also divided into towns:

In 1687 and 1688, the English divided the island into four administrative divisions based on natural features: the 5,100-acre manorial estate of colonial governor Thomas Dongan in the northeastern hills known as the “Lordship or Manner of Cassiltown,” along with the North, South, and West divisions. These divisions later evolved into the four towns of Castleton, Northfield, Southfield, and Westfield. In 1698, the population was 727. wikipedia

In 1860, parts of Castleton and Southfield were reapportioned as the Town of Middleton. The boundaries of Staten Island’s former towns can be seen on this 1874 Beers Atlas plate. When Staten Island became part of Greater New York, its separate towns were dissolved. Northfield, Westfield, and Castleton are remembered by street names.

Two views of the hulking LNG (liquid natural gas) tanks, seen from Bloomingdale Road and Winant Avenue. I was surprised to learn that these tanks are only about 40 years old and that they have never been used!

Veterans Road East, the southern service road of the West Shore Expressway. I’m quite familiar with this road, since I would use it as a sort of “bike expressway” in 1977. Why 1977? That summer, years before assisting bicyclists became NYC policy, the Transit Authority, as it was called, operated a special bike bus on weekends from the 95th Street station on the R train in Bay Ridge across the Verrazano, ending just across the bridge on Fingerboard Road. I could bike to my heart’s content all over the island, which I did on what must have been about 4 or 5 occasions, though this stretch of road is the only one I recall with any specificity. You had to be back at Fingerboard Road by 4 PM, or else head to St. George and take the ferry to Manhattan and then ride the bike or subway back to Brooklyn. I didn’t miss the cutoff, though. The bike bus was a regulation GM fishbowl bus with the seats removed to fit the bikes; then as now, there were no bikes allowed on the Verrazano Bridge. The TA ended the service after one summer.

Also notice the special telephone pole stanchions along the service road. These are different from the usual finned masts generally found on side streets with telephone poles, and though the special posts have been there as long as the finned ones, perhaps longer, they just don’t rust. I’d advise using them all over town, not just on parkways!

St. Joseph’s Church, on Rossville and Poplar Avenues, is Staten Island’s second-oldest Catholic parish (St. Peter’s Church, founded in 1839 on St. Mark’s Place in St. George — confusing, eh– is the oldest). The cornerstone of this modest country church was laid in 1849 and the church was dedicated two years later. This is the oldest Catholic church building in continuous use on the island.

As stated earlier, Rossville is made up mainly of tract housing or small garden apartment complexes. Occasionally, though, you see some aged leftovers from the old days, like this house at Rossville and Poplar Avenues. It escaped the 1973 fire and later construction of the West Shore Expressway.

Barry Street, ultimately a dead end, has a surprise toward the end of the street. It’s one of Rossville’s older streets, and shows up on the 1873 atlas (see above) as “Glen Avenue.”

Schindler Court, possibly named for the World War II hero, is typical of latterday Staten Island private housing developments. In many cases the city’s Department of Transportation has ceded the job of marking these new streets, and so you have atypical signs that are cross-mounted, a scheme found often outside New York City, but rarely within.

Barry Street is named for Reverend John Barry, an early pastor of St. Joseph’s. In the 1860s, Fr. Barry purchased land to the rear of St. Joseph’s Church for use as its burial grounds; the first interment was in 1867. It’s amazing to think that, in the 1860s, St. Joseph’s made do for Catholics in the communities of Rossville, Greenridge, Annadale, Prince’s Bay, Richmond Valley and even Tottenville. There were few roads, and horses and wagons or sleighs were the best modes of transportation.

Since St. Joseph’s Cemetery served the church parishioners, you will not find the “old names of Staten Island” here as you would in other aged area cemeteries, but there are planty of Irish, Italian, and Czech names. Over a dozen Civil War veterans are found here. And there’s a mystery, to me, at least…

There are a number of modest, hand-lettered stone markers, all but one topped by crosses, toward the back of the cemetery. It’s hard to make out the lettering but they seem to be in an Eastern European language. Hungarian, perhaps? However, I seem to be seeing some Cyrillic characters as well, which would mean Bulgarian or Russian. If you recognize it, let me know in Comments.

Way late for this week’s page — the rest of Rossville, including Sandy Ground, coming soon.

6/22/14

19 comments

http://www.cityoftombstone.com/

Tombstone, AZ features a great re-enactment of the OK Coral incident several times daily.

Re: Crazy Goat Feeds – aside from the initials CG what connects Clark Gable to this establishment? I can’t find any mention of it (at least in Wikipedia)

I don’t know for sure but an educated guess would be Hungarian. B. Kreicher may have employed workers at the nearby brick works from his native Hungary.

looking for distribution space buy the water and rail road tracks please get back to me kelly

I think the real reason why Staten Island is unknown to most New Yorkers could be that it’s the only borough without a subway line to connect it to the rest making it hard to get there without driving for most.

Another awesome job, Kevin. I’ve often wondered why Staten Island seems to be persona non grata to many residents of the other boroughs, and my only guess is that the relative geographic isolation (I say relative because it really isn’t that far from Manhattan or Brooklyn) and the fact that, since the Revolutionary War, the Island has been very “contrarian” in its outlook, being pro-British (at least when the war started) and never quite seeing things that its sister boroughs do. Philip Pappas’ excellent book “That Ever Loyal Island” gives a great account of SI during the war, and how the British troops felt right at home, at least until they started burning bridges (and fences, and anything else they could get their hands on), stealing livestock and molesting women.

Alas, any New Yorker why doesn’t visit and/or explore all five boroughs is missing out on some amazing local history, as your post shows. Staten Island, more than any other borough, has saved a lot of it, even if only in small ways like abandoned shipyards and 250-year-old cemetery tombstones. I hope more folks decide to take day trips and explore as you do; I think they’d be in for a pleasant surprise.

You do such an excellent job…..I always regret not exploring Staten Island in more detail before I moved to the West Coast…

great photos get more!

I’m surprised you don’t mention the February 1973 gas explosion in nearby Bloomfield, which killed over 40 workers. This is the reason why those two tanks sit rusting: They were under construction at the time, and local opposition killed their chances of ever opening. www3.gendisasters.com/new-york/1108/staten-island,-ny-explosion,-feb-1913

Kevin,

I was miles away in a parking lot on a southwest facing hillside at Wagner College when the Rossville LNG tanks tragedy occurred in 1973, and my car was rocked by the loudest boom I’ve ever heard or felt; it was very frightening.

Now you know why the tanks were never used:

http://www.silive.com/specialreports/index.ssf/2011/03/lng_explosion_kills_40_destroy.html

I was sitting with my Dad at our West Brighton home, a good four miles away, and the whole damned house shook like a San Francisco earthquake. While I’m not surprised they never opened the other two LNG tanks, I do wonder why they never tore them down.

Sorry, my previous comment should have read: “… when the BLOOMFIELD LNG tanks tragedy occurred.” … “Now you know why the ROSSVILLE tanks were never used.”

The feed store owner was named Clark Gable, but he was not THE Clark Gable. The feed store was originally located at the stable he owned, either on Sharrotts or Englewood.

Hm, I wonder why both my references would mention Clark Gable, without meaning “the” Clark Gable. Since neither say he is, I’ll fix it.

Those tanks never got used because of an explosion that killed forty or so workers

It hadda happen Kevin…You with the camera phone! We’ve come along way.

Excellent pictures!!!

re: Feed Store. Is that the “Crazy Eddie” type style?

I don’t have a camera phone …

I REMEMBER THE DAY OF THE FIRE/1973, GOING DOWN TO ARTHUR KILL ROAD TO A WOMAN WHO SOLD FLOWERS/PLANTS, THEN MY GIRLFRIEND AND I TRYING TO GET BACK THE WAY WE CAME (FROM ELTINGVILLE) AND THERE WAS FIRE AND SMOKE ALL

OVER. WE WERE FINE, BUT WHAT A TERRIBLE DAY.

ALSO I SEEM TO REMEMBER A PERSON NAMED CLARK GABLE, HIGH SCHOOL (?), 1950-1954……….

ROSSVILLE WAS REALLY COUNTRY AND NICE. I WAS BACK IN STATEN ISLAND LAST YEAR AND WAS SAD TO SEE SO MUCH HOUSING BEING BUILT. ONE STORY HOMES BEING CONVERTED TO TWO STORY HOMES, ETC. ALL THE LAND WE HAD IN ANNADALE, ELTINGVILLE, ETC. FILLED WITH SO MANY HOMES AND SO LITTLE YARDS,,,,,,,OH WELL, THAT’S PROGRESS I GUESS…………..

I have climbed the those tanks as shown in the photos. You have to climb 4 rusted old ladders since the stairs are half destroyed. The view from the top is beautiful and well worth the climb.

When the gas tanks exploded in 1973, it was the loudest explosion I ever heard … to date. I was 17 then, and our apt. in Queens over 30 miles away trembled for seconds. The NYC earthquake of the late eighties, which threw me out of bed, was not quite as memorable! How horrific for those involved.