In my collection of NYC books I think I can count the number of books on (exclusively) Staten Island with two hands. There’s Holden’s Staten Island, Secret Places of Staten Island, any one of John Sublett’s self-published Staten Island books, and Staten Island neighborhoods in the Arcadia photo books series. Not one of those books are on a major publishing house imprint (though Arcadia does have hundreds of editions nationwide). In my edition of New York City Landmarks, Staten Island takes up 35 pages out of 452; in the AIA Guide to New York City, Staten Island takes 53 pages out of 1056. In Forgotten New York the Book, I give Staten Island what I feel is a decent portion, 55 pages out of 360.

So I walk the Staten Island hills, snapping away at anything remotely interesting, and consult the wilderness of the world wide web for any scattered information. I was determined to walk plenty of streets that the AIA Guide or NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission people have apparently never been. (Though the buildings on St. Paul’s Avenue and some of the immediately surrounding streets are protected by the Landmarks Commission, and FNY and tourgoers were guests in a couple of those homes in a 2014 ForgottenTour, none of the other areas have been granted protection.)

GOOGLE MAP: St. George—Tompkinsville—Park Hill—Stapleton

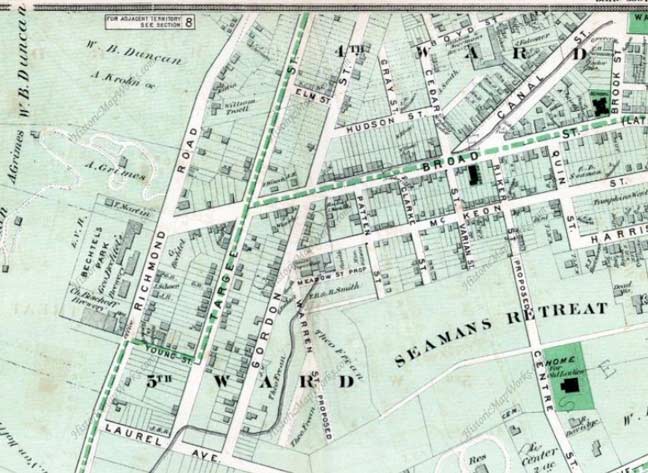

In large part the 1873 map of this area works just as well today as it did then, with some street name changes. The area of the map marked “Seaman’s Retreat” was not the present Sailors’ Snug Harbor Retreat, which was founded at Manhattan’s Washington Square at the bequest of Revolutionary War soldier and sea captain Robert Richard Randall (1750?-1801) and moved to Staten Island’s North Shore in 1833. This lesser-known seaman’s retreat was founded on what was later the site of the home park of the Staten Island Stapletons football team, which competed for two years in the 1930s in the NFL, and today is the site of the Stapleton Houses.

This Seaman’s Retreat later gave rise to Bayley-Seton Hospital (see below).

I walked east on Laurel Avenue and then north on Gordon Street, which shows up on the 1873 map running parallel to Targee Street for all of its length. I had never been on Gordon Street before, so I decided to take a look at it.

This is the northernmost section of Park Hill, or perhaps as far south as Stapleton goes.

From my 3-part page chronicling my latest visit to Arrochar, Grasmere, Concord, Clifton and Rosebank in 2013…

Park Hill, with Stapleton, forms some of Staten Island’s poor sides of town, along with locales like Mariners’ Harbor and parts of New Brighton. This is another aged building camouflaging its age under several layers of siding at Targee and Metcalfe Streets.

The Park Hill Apartments, a privately owned but federally subsidized low-income housing complex on Vanderbilt Avenue, and also on Park Hill Avenue, became the site of steadily increasing crime and drug abuse beginning in the mid-1960s; by the late 1980s it had gained the nickname of “Crack Hill” due to the many arrests for possession and/or sale of crack cocaine that were taking place in and around the development and the adjacent Fox Hills Apartments to the south. However, crime in this area has dramatically decreased since the late 1990s. Community activists are addressing the ongoing conflict between Liberian and African American youth, primarily between the ages of 10-14. The community organizations run after-school programs to help keep the youth occupied in a productive way. This helps curb gang and street violence. The community tension that occurs in Park Hill is based on poverty and unemployment. wikipedia

Park Hill became known as “Little Liberia” after refugees from a civil war in 2007 in the western African country immigrated to the neighborhood.

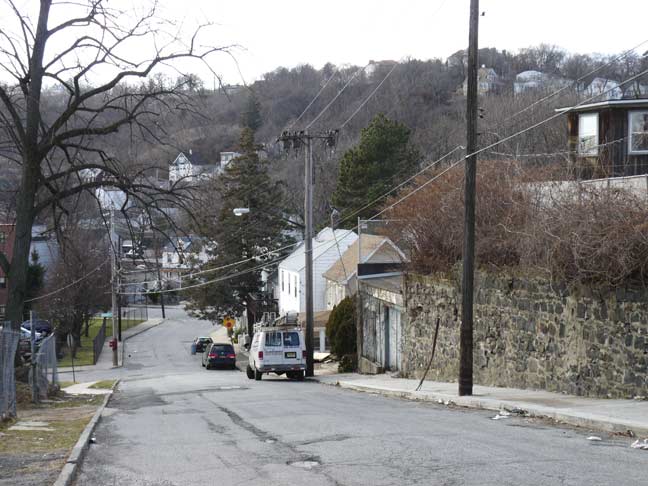

Gordon Street (seen here on Google Street View) has a lengthy, uninterrupted stretch between Laurel Avenue at the south and Warren Street in the north. The length of the street is marked by private one and two-story homes (now and then a newer 3-story house and others with an attic or cupola), many of them perhaps over a century old; their age is hidden by modern aluminum siding.

This house appears to have had an upper floor shown off; with its curtains drawn both here and in GSV, it may not be inhabited. The other houses along Gordon Street are well-kept.

A look at the Stapleton Houses as seen from Broad and Gordon Streets. NYC Housing Authority: Stapleton Houses is the largest (housing) development on Staten Island. There are six, 8-story buildings, with 693 apartments housing about 2,148 residents. Tompkins Avenue, Broad, Hill, Warren and Gordon Streets border the 17.94-acre complex, completed May 31, 1962.

Rappers the Wu-Tang Clan, actor/rapper Method Man as well as actor/musician Tristan Wilds all hail from the Stapleton Houses.

Much more on artists hailing from NYC’s housing projects

On Gordon Street between Broad and Hudson, this is the parochial school associated with Immaculate Conception parish (see part 2, linked above, for the church. The church was erected in 1908 and the school in 1927.

Hudson Street is part of a complicated little maze of streets in southern Stapleton, along with Gray, Cedar, Boyd, Court, and Grove. The houses on Hudson seem to be of more recent vintage than the saltboxes on Gordon.

There’s a stepped brick structure on the corner of Hudson and Gray Streets. It may have been a stables but other than that I can’t guess what its original purpose was. There is some very faded stenciled writing on the arched brickwork. Anyone know what it says?

Gray Street runs officially for one block in the maze, curving between Hudson and Gordon Streets. The neat brick building at the end of the street is a senior home, St. Elizabeth Boyle Manor.

A trio of houses on Hudson Street facing Gray…

… and a very small house on Gray that nevertheless has room for a wrap porch and two dormer windows. I’d have loved to see this one years ago before the siding.

Oddly, a narrow footpath issuing midblock is marked by a Boyd Street sign. hat’s because if you follow the path, as I did, it opens onto the actual Boyd Street, which dead-ends for vehicular traffic a little past Cedar Street. This feature is not shown on any map, not even Google Street View, which is normally quite thorough.

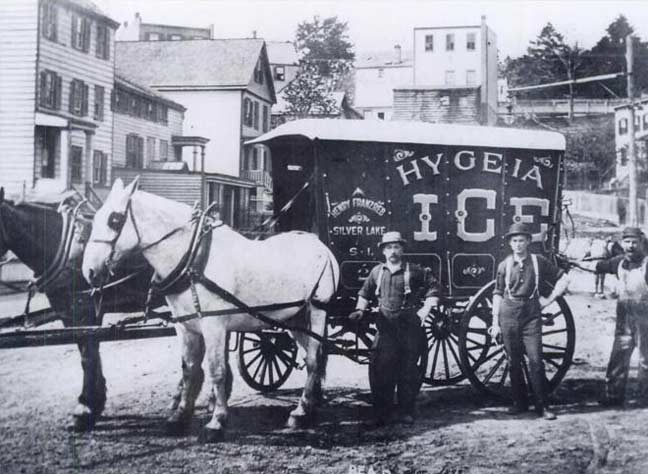

The one-block Hygeia Place runs between Boyd and Grove Streets. Before 1915 or so it was Henry Street but then its name was changed to Hyegeia, one of two streets in Staten Island named for a Greek goddess. The other is Minerva Place, in New Brighton.

The name may have something to do with the Hygeia Ice Company, one of many private firms supplying ice on Staten Island in the early 20th Century, a major enterprise in the days before universal refrigeration. As a kid in Bay Ridge, ice trucks still provided these services.

I have shot this view from Boyd Street and Hygeia Place often, but it’s one of my favorite views. A downslope makes Grymes and Ward Hills look taller than they are, but they are still among the taller peaks on the immediate East Coast. I’m somewhat envious of cities that have mountain views, but at least we have a bit of that here.

Court Street is yet one more one-block street in the maze, running from Boyd to the intersection of Grove and Van Duzer. The former Second Empire-style brick courthouse, built in 1888, for which the street is named remains in place as a private residence or residences.

Grove Street also looks down toward the Staten Island hills. The retaining wall separates the street from houses facing Van Duzer Street (see part 2 for those).

From Boyd Street and Tappen Court (also spelled Tappan on some signs) the old Bayley-Seton Hospital can be seen in the distance. It was founded as the Seaman’s Retreat in 1831 to serve retired sailors and naval officers. Later it expanded when the Laboratory of Hygiene for Bacteriological Investigation, later National Institutes of Health, opened offices and labs there. When the Sisters of Charity took over the property in 1980 it was renamed for Elizabeth Ann Seton (1774-1821), the first American-born saint (canonized in 1975) and her father Richard Bayley, both of whom lived on Staten Island. Many of the campus buildings have been closed and only the hospital’s psychological offices remain open in 2015.

Some of the handsome buildings along Boyd Street between Court and Wright Streets, some of which go back to the 1870s. Again, you can only wonder what they looked like before the siding was slapped on.

In spots, the blacktop on Boyd Street is wearing down so the original brick paving comes through.

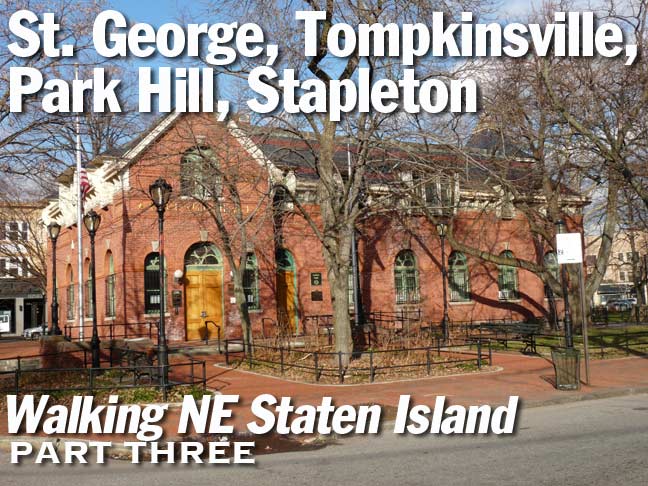

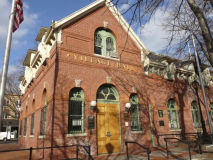

Bandshell and Edgewater Village Hall in Tappen Park at Wright and Water Streets. (I’ll discuss edgewater Village Hall in a minute.)

Tappen Park may be smallish (1.78 acres, defined by Canal, Wright, Water and Bay Streets) but it is surrounded by some prime 19th and 20th Century architecture. The park was founded in 1867 as Washington Square and was then called Stapleton Park, but since the 1934 it has been named for James J. Tappen, a local soldier who perished in World War I’s Battle of Argonne.

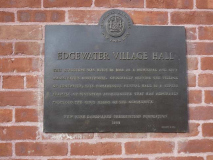

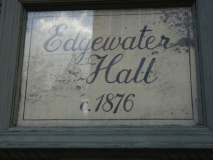

Edgewater Village Hall

Just as Kings County was once divided into six separate towns, so was Staten Island: the Town of Castleton comprised St. George, New Brighton, and Livingston; Edgewater consisted of Tompkinsville, Stapleton, and Clifton; Southfield, the entire South Beach area including Grant City and Dongan Hills; Middletown, the Todt Hill region; Northfield was the entire northwest of the island including Port Richmond, Mariners Harbor, Graniteville and Travis; and Southfield, most of the south shore including Richmondtown, Greenridge, Annadale, Huguenot, Prince’s Bay, Richmond Valley and Tottenville. These town distinctions were erased when Staten Island joined NYC in 1898.

This red brick Romanesque Revival edifice, designed by Stapleton resident Paul Kuhne in 1889 in Tappen Park, at Wright and Canal Streets, is Staten Island’s only remaining village hall (the New Brighton village hall, after nearly fifty years of abandonment, was razed in 2004). Stapleton was part of Edgewater Village, in turn a part of Middletown, one of Staten Island’s five towns, a political division done away with when Staten Island became a part of New York City in 1898.

Unfortunately, the village hall is generally closed to the public and is used for local municipal organizations’ offices. I was able to sneak inside the front door and get a photo of a plaque inscribed in ecclesiastical-style lettering, listing the names of Edgewater Village officials.

I’m a big fan of this map of Stapleton posted outside the Village Hall highlighting area buildings, neighborhood history and former landmarks (Stapleton used to be the brewing center of Staten Island) but the map does get Gordon and Warren Streets mixed up.

The Staten Island Savings Bank at Water and Beach Streets was not the first bank opened on the island, but was the first to be successful. Richmond County Bank, founded by Richard D. Littell, a judge in the court of special sessions, had been chartered by the State of New York in 1838 but failed by 1842, leaving Staten Island without its own bank until after the Civil War.

The Staten Island Savings Bank was originally incorporated by the State of New York on April 6, 1864 but for unknown reasons did not begin operations until 1867. Founded by twenty-one prominent Staten Island men including Francis Gould Shaw, a philanthropist and reformer, John Bechtel, founder of Bechtel Brewery and Louis H. Meyer, its first president, a business man specializing in securities and railroad reorganizations, the intention was to provide the working men and women of the surrounding communities with a secure place to deposit their savings. The first deposit, $100, was made by Mary Josephine Thiery on June 8, 1867, shortly after the bank received its amended charter from the state.

The neo-Classical style Staten Island Savings Bank was constructed on the prominent corner of Water and Beach Streets in downtown Stapleton in 1924-25. Designed by the nationally-significant firm of Delano & Aldrich , it is an important example of twentieth-century Italian Renaissance e-inspired neo-Classicism in Staten Island. The architects took advantage of the acute angle of the site to create a dramatic entrance of a colonnaded portico with a fish-scaled cast-lead dome.

Philanthopist and industrialist Andrew Carnegie built 1,689 libraries across the U.S., striking the same bargain each time: He paid for construction in return for a guarantee that they were operated and maintained with taxpayer funds. Of the 67 built in New York City, 53 are still in use.

The so-called Carnegie branches, built between 1902 and 1929, are costlier than others to repair, maintain and upgrade. The buildings generally aren’t handicapped accessible, and their layouts don’t always serve modern needs. Many are landmarked, making renovations pricier. WSJ

In 2013, the New York Public Library reopened its Stapleton branch on Staten Island at Canal and Wright Streets, offering patrons a newly-renovated library that is more than double its original size, and that seamlessly combines the charm of an original “Carnegie Library” with a beautiful and highly-functional modern addition.

The renovated Stapleton Library includes a light-filled, sleek, 7,000-square-foot addition connected to the original 4,800 square-foot-branch, a Carnegie Library originally built in 1907. The original library has been restored as the new children’s room. Public space has more than doubled, and new interior features include reading rooms, lounges and areas for toddlers, children, teens and adults, ADA accessibility, 40 new public access computers, 10 laptops available for patron use, WiFi capability, and a multipurpose community room.

A Uneeda Biscuit ad from the 1910s can still be seen faintly on a Canal Street building on the south side of Tappen Park.

The National Biscuit Company was formed in 1898 by a merger of the midwest American Bakeries and the eastern New York Biscuit Company, while these companies, in turn, had been formed by mergers of much smaller local bakery firms. The next year, 1899, Nabisco, as the firm came to be known, controlled hundreds of bakeries and reported an income of $55 million annually. Nabisco then launched its first national product, a soda cracker, and contracted ad giant N.W. Ayer to devise a name and a campaign, and the era’s Don Drapers arrived at the punny Uneeda.

At the same time, cardboard packaging and wax paper wrapping was beginning to catch on, instead of the previous methods of cracker barrels and crates. Bread products could now be moved to store shelves easily and protected from spoilage. Ayer devised ads featuring the Uneeda Boy, clutching a box of Uneeda in various scenarios. Even the streamlined sanserif lettering on the package and the ads pointed toward a mid-20th Century esthetic.

Nabisco also delved into the billboard and painted ad method of advertising, pasting the distinctive Uneeda Biscuit lettering on thousands of buildings. Like Fletcher’s Castoria painted ads, many of them have stubbornly held on to this day, like this one at Canal and Wright Streets in Stapleton, Staten Island.

In subsequent years Nabisco devised dozens of popular cracker and cookie brands, such as Oreo in 1912, still the USA’s most popular cookie brand. Nabisco merged with Standard Brands in 1981 and was purchased by RJ Reynolds in 1985, creating a snack food monopoly that also included Planters’ Nuts and Life Savers candy. Uneeda’s sales had decreased and it was far from its early eminence as the star of the brand, and Uneeda was discontinued in 2008.

Also note the old version of the Nabisco logo, described by some as a TV antenna on a football. Company literature claims it was derived from an “early European symbol for quality” which may be a reference to printer’s marks that were used on medieval manuscripts.

Area sidewalks on the streets near Tappen Park are illuminated by park lamps mounted on short brackets mounted on telephone poles. This method is rarely used in NYC — I’ve only seen it in East New York on New Lots Avenue, of all places.

Moving on to Bay Street in Stapleton, at Jerry’s “637” Diner at #637 is this glorious illuminated restaurant sign. The coffee shop is only open for breakfast and lunch, though.

Some premier architecture can be found along this stretch of Bay Street, including these two buildings flanking Thompson Street. North of Tappen Park, the 1930s Paramount Theater awaits redevelopment, as it has for thirty years.

Not to be confused with the Edgewater village hall in Tappen Park, this three-story red brick building at 691 Bay Street on the corner of Dock Street is one of Stapleton’s most distinctive commercial buildings. When built in 1876, the hall was the first home of the Staten Island Savings Bank; the bank’s brick arches and vault can still be found in the interior. In the 1970s the Hall was home to a rock club; Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna played here.

At #710 Bay Street is the landmarked 1848 Italianate villa built for Dr. James Boardman, the physician at the nearby Seaman’s Retreat (later Bayley Seton) Hospital. It was later purchased in 1894 by a Captain Mitchell with money he was awarded for rescuing all 176 persons aboard a Cunard liner that sank in Long Island Sound. The Cunard family had a number of mansions in the Staten Island hills.

Dock Street is one of the shortest dead ends in Staten Island, issuing just a few feet off Bay Street, just enough room for a side door into the pub located in Edgewater Hall.

At Bay and Dock is also one of the few remaining stone-wrought sewer grates remaining in NYC.

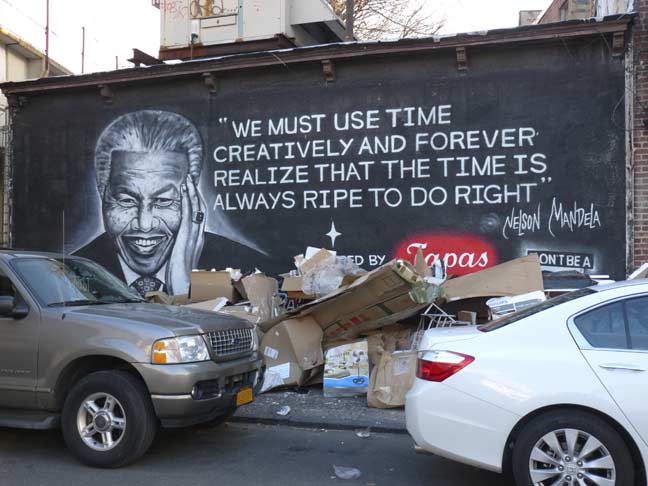

Tapas Restaurant, at Bay and Thompson Streets, sponsored this mural featuring Nelson Mandela (1918-2013), the longtime South African leader.

When you sponsor an outdoor mural, you take the chance that the sidewalk in front of it might become a dumping ground.

The Staten Island Railway, originally Staten Island Rapid Transit, is trestled along the short streets leading from Bay Street to the waterfront. From FNY’s Staten Island Railway page:

Non-residents of Staten Island may not know that the borough has its very own rail line which, although resembling a subway, isn’t run as a subway at all. Formerly known as Staten Island Rapid Transit, the Staten Island Railway was begun by Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1851 for the purposes of linking Vanderbilt’s Landing in Stapleton to Clifton. By 1860, the line was extended to Eltingville, then on to Annadale, and finally to Tottenville.

In 1883, Erastus Wiman, in partnership with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, built a line to South Beach and along the North Shore. By 1885, what would become the SIRT was complete, with the completion of the tunnel between Stapleton and the St. George Ferry. The ferry terminal opened in 1897 (the present-day terminal was constructed in 1951 after the original was destroyed in a fire in 1946).

By 1953, ridership had dropped to such a degree (due to reduced bus fares) that the B&O threatened to terminate all passenger service. The City agreed to subsidize service on the Tottenville line and terminate service on the North Shore and South Beach branches. The B&O ended its involvement with Staten Island Rapid Transit in 1971, selling it to NYC for $3.5 million. Quaint B&O passenger coaches that had operated on the line since 1925 were replaced by modern R-44 subway cars. Finally, the MTA changed the name of the SIRT in 1994, renaming it the Staten Island Railway.

As the date stamped on the trestle proves, here the railway eliminated grade crossings in 1936.

For much more, including information on all the neighborhoods the SIR passes through, see FNY’s Stations of the Staten Island Railway pages.

The section of Water Street that passes under the railway between Bay and front Streets is subnamed for Commodore John Barry. It seems to be rather disrespectful to name so onscure a route for the great military commander.

Commodore Barry (1745-1803), known as the “father of the American Navy,” was born in Ireland, went to sea as a youth and quickly rose in the ranks from cabin boy to captain of the shipping vessel Black Prince. He served with success in the American Revolution, making the first American capture at sea of a British vessel, and made several others during the war; the sale of these vessels helped fund the nascent US Congress. In 1781 he escorted the Marquis de Lafayette on a mission to America. Barry helped found the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1801, which constructed US vessels until 1966.

Front Street runs along the waterfront along Upper New York Bay between Tompkinsville and Clifton. The waterfront area had been slated in 1983 to serve as the Staten Island Homeport, a naval unit where the USS Iowa would be berthed. The plan was largely scotched due to fears about local residents being displaced for jobs by Homeport personnel as well as fears that nuclear missiles would be located on board the battleship.

The Homeport was cancelled in 1993, and the waterfront area was then largely quiet except for small local businesses till 2014, when construction of an upscale housing project called URL, or “Urban Ready Life,” a $250 million mixed-use project with about 900 rental apartments slated for a series of buildings resembling factories, with bands of windows and flat roofs. The skeleton of a couple of the buildings had appeared by late 2014.

At its northern end, Front Street makes a bend and turns into Murray Hulbert Avenue (though the Department of Transportation doesn’t immediately acknowledge the change). The lack of a sidewalk is a subtle indicator that mere pedestrians like me aren’t supposed to be here.

From FNY’s NYC Streets Featuring Full Names page…

US Congressman from 1914-1918 Murray Hulbert (1881-1950) served as President of the New York Board of Aldermen (today’s City Council President) under John “Red Mike” Hylan and briefly stepped in for Hylan during an illness in 1921. He served as Commissioner of Docks and Director of the Port of New York from 1918-1921, which likely explains the presence of a Murray Hulbert Avenue along the waterside.

Clichéd adjectives such as “breathtaking” and “awe-inspiring” can be used for the views of Lower Manhattan featuring #1 World Trade Center, as well as Brooklyn’s Williamsburg Bank Tower (officially #1 Hanson Place) and the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge available from Murray Hulbert Avenue.

The views are made that much juicier by the fact that they are illicit, since You’re Not Really Supposed to Be Here.

You’re not supposed to be here because there are very important businesses here, machine works, storage areas and maritime businesses — baseball-capped grotesques with cameras skulking around are viewed quite suspiciously in these parts. There’s also the lack of a sidewalk or a shoulder, and speeding vehicles along the straightaway.

It was the Yuletide when I passed this remove. Local workers celebrate the season as best they can. (Well, the workers are probably all unionized and have hefty paychecks and health care, but it’s still hard work after all.)

Murray Hulbert Avenue is finally identified as such at Hannah Street (named for a daughter of Daniel Tompkins) which features a bridge over the Staten Island Railway into the heart of Tompkinsville. Before leaving the waterfront…

… I was able to get a dramatic shot of a staten Island Ferry passing the skyline.

After passing over the railroad…

…. the familiar Staten Island Borough Hall was in sight, and with it, my means of getting back home to Little Neck: a ferry, a subway, and a railroad.

5/24/15

14 comments

Since you like mountain views…

http://www.bing.com/images/search?q=prescott+az&qpvt=prescott+az&qpvt=prescott+az&FORM=IARRSM

More mountain, less water

The writing on the stepped brick building appears to say Distributing Station, with the ‘in’ obscured.

The faded lettering on the stepped-front brick building says something like “Distributing Station” or similar words.

I have walked on Front/Hulbert-there used to be a walkway until the water tunnel work- which you call machine works in your photos. It is a year behind schedule because of Sandy.

Regarding the “stepped brick structure on the corner of Hudson and Gray Streets.”

The photos provided seem to read “New [ something ] Distributing Station” over what was certainly a wider arched entrance.

The map doesn’t leave many hints, but it doesn’t appear to be a ‘power’ distributing station, nor does it fit as a car barn for a streetcar line. Needs boots on the ground.

As best I can tell, the building at 27 Hudson St was a distributing station for the New York municipal water system. You can make out the words NEW YORK DISTRIBUTING SYSTEM over the door. The NYC.gov map shows it being constructed in 1931, approx 14 years after NYC took over Staten Island’s water supply from private companies and connected the borough to the Catskill water supply tunnel. Since the building is too small for a power distribution system, and since much of the literature from the period uses the word DISTRIBUTING in connection with water supply (as opposed to DISTRIBUTION for power/gas systems), I’ll wager it was a water distributing center for Stapleton and nearby areas. The city probably sold off old, outdated structures such as this, which is now owned by a local church.

I think you hit on the REAL reason they closed the Brooklyn navy yard-the rich didnt want nukes

in n.y.

After all,the D.O.D. wouldnt close another govt. yard for at least another 25 years when they closed

Philadelphia navy yard

http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e4-7345-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

1907 Sanborn map shows “Staten Island Hygeia Ice & Cold Storage” on Henry Street. It also shows Boyd Street running to Gray Street at full width but unpaved. Somehow the property owner on the north managed to encroach enough to make Boyd end at a point with just a footpath left at the end! The brick building at Hudson and Gray is not there yet in this 1907 map even though it looks older than that. The property lines in this area are quite a tangle left from many uncoordinated subdivisions.

There’s a Sanborn Fire Insurance map of that corner from 1936 which says ___ ____________ DISTRIBUTING STATION. For the life of me, I can’t enlarge it enough on my computer to figure out what the first two words are, but if I had to guess it somewhat looks like MUN (icipal) RESERVOIR DISTRIBUTING STATION. If anyone can figure out how to enlarge that map with getting a mega-pixelated version, it’s on the NYPL digital image website, Sanborn Map of Staten Island, Vol 1, No 26 (original from 1917, updated version 1936). The 1917 version map is very clear but just shows an unnamed commercial structure about the same size at the corner of Hudson/Gray.

I haven’t taken the time yet to read all of the above, I just found part two, but I do love the pictures. So many memories came back. Thank you.

Absolutely love this.. brings back so many memories of “home”..

Looking at the Beach Street photos, there was a walk-up Chinese Restaurant that I believe was at one time the re-located Republic Gardens, 1965 or so, then changed the name. I think it was Wah Ting, does anyone remember?

My great great Grandfather Jacob Benjamin Wood lived on Richmond Street in Tompkinsville. I have his tax statement showing that he owned and lived in a house on Richmond Street in Tompkinsville. I also have his will where it states he was leaving his home on Richmond Street in Tompkinsville. My Grandfather died in 1865. I know that Richmond Street no longer exists however, I would like to know the new name.

I lived on Hudson Street from 1963-1973. The building

on the corner of Hudson &Gray was a sewing factory and had been there for years.