Continued from Part 1

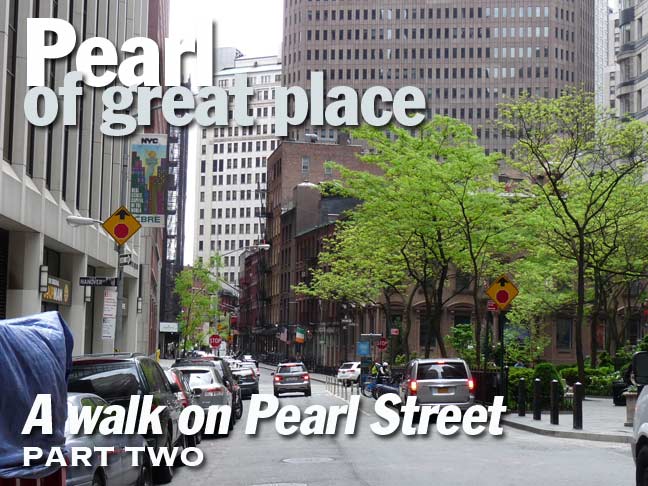

In May 2016 I decided to walk up Pearl Street’s entire length from Battery Park to Tribeca. It’s an oddly positioned street, as far as downtown goes, first running northeast, then gradually turning northerly and even westerly. Its entire length once ran to Broadway and Thomas Street, though it has been trimmed back from that due to mid-20th Century constructions. Because of the Landmarks Preservation Commission’s two separate landmarked districts, Pearl Street, unlike most downtown Financial Street ways, looks much as it did in the 19th Century along some stretches; other streets downtown run through concrete, masonry or glass canyons…

There’s a very good reason I decided to walk Pearl Street — unlike most of lower Manhattan, Pearl Street is a building museum in spots, with several walkup residences somehow avoiding the relentless pace of change. Unfortunately this pair of buildings is on the south side of Pearl, which is not a part of the Stone Street landmarked district on the north side of Pearl between Coenties Slip and Hanover Square. That means a developer could knock them down and replace them with more glass towers. I hope that day is still some distance away.

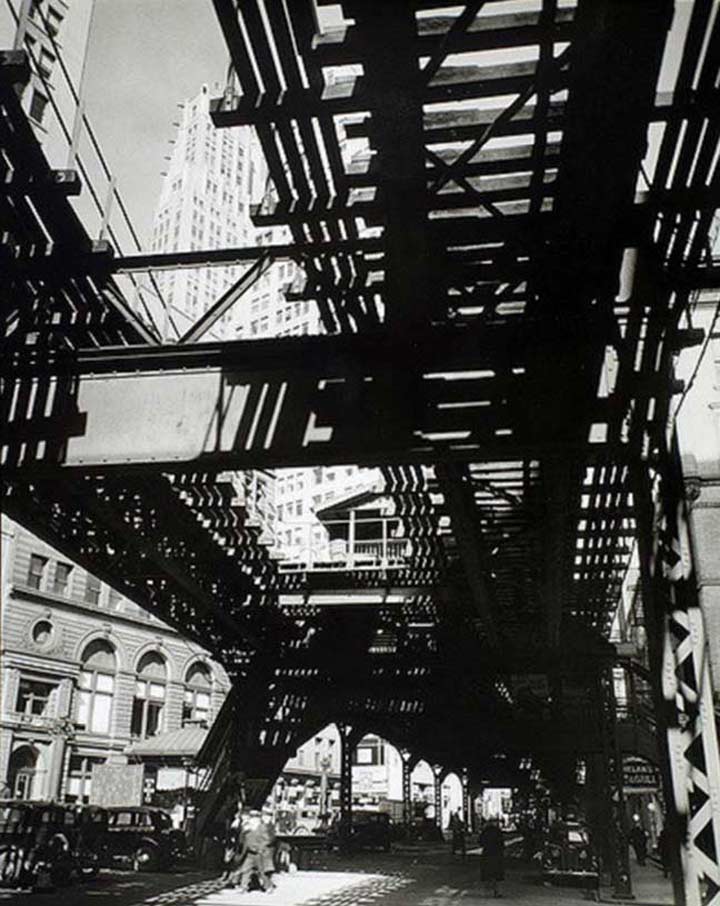

Note the gray building on the corner of Coenties with a chamfered, or slanted, edge. There’s a very good reason that the slant is there. It once accommodated a curve in an elevated train.

As this map indicates lower Manhattan was rife with elevateds at one time. The 2nd, 3rd, 6th and 9th Avenue Els all originated at the Bowery at what is now Peter Minuit Plaza, Whitehall and South Streets. Routes fanned out, going up Greenwich Street, Trinity Place/Church Street, and Water Street. One branch made a sweeping curve at Coenties Slip and then followed Pearl Street to Chatham Square at the Bowery and East Broadway in Chinatown, where it separated into the 2nd and 3rd Avenue Els.

Pearl Street at Hanover Square, 1920s

The north side of Pearl between Coenties and Hanover, meanwhile, still contains a number of very old brick walkups, most of which were constructed between 1836 and 1840. The reason for this is that a great fire swept through lower Manhattan in December of 1835 on a night that the temperature reached 10 below or lower, conditions not seen in NYC anymore; water froze before the volunteer fire departments then answering the call could put it on the fire. Most of lower Manhattan’s wood frame buildings, including some dating back to the Dutch colonial era, were lost forever. Ordinances prohibiting new wood frame buildings on the island were enacted in the next few decades. Developers moved quickly to rebuild and many of the buildings that went up just after the fire are still in place, protected by NYC Landmarks, along the north side of Pearl, on Stone Street, and on South William Street.

The buildings seen along the north side of Pearl actually are the back ends of buildings that face Stone Street, which has been turned into a pedestrian Restaurant and Bar Row in recent years accommodating downtown workers during the week and vacationers and tourists on the weekends.

#79 and #81 Pearl are home to Route 66 Smokehouse and Beckett’s, respectively. A close look at the exterior of #81 reveals something interesting.

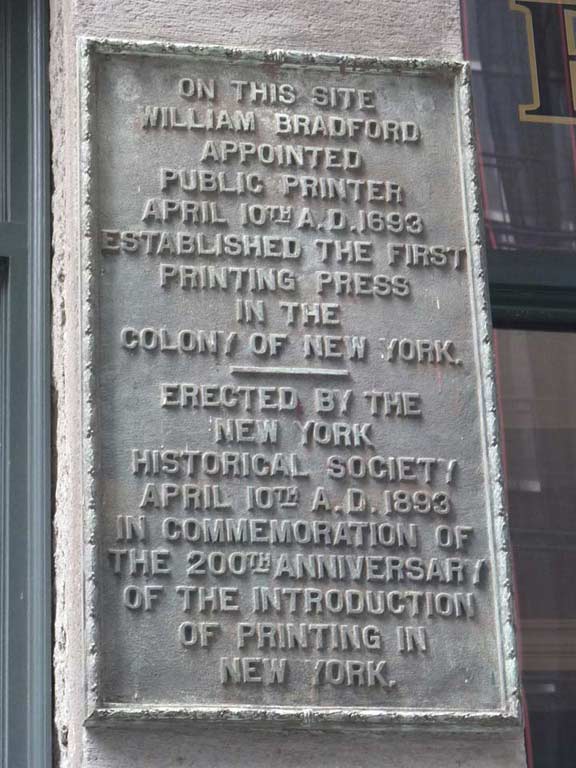

…an ancient plaque, placed in 1893 by the New York Historical Society, marking it as the site where the first printing press was established by William Bradford (1663-1752) in 1693.

In 1693, Bradford applied for and was appointed to the position of public printer for New York. He lived on Pearl Street in Manhattan, then moved to Stone Street in 1698. His offices were located in Hanover Square. In 1702, he was appointed public printer of New Jersey (a post held concurrently with his New York position), and became clerk of the New Jersey assembly in 1710.

Bradford printed the first book in New York City, “New-England’s Spirit of Persecution Transmitted to Pennsylvania” in 1693 by George Keith, a Quaker political writer.

In 1723 when Benjamin Franklin was in New York immediately after leaving Boston he approached Bradford for employment, and Bradford referred him to his son in Philadelphia.

Between 1725-1744, Bradford printed the New-York Gazette, New York’s first newspaper. In 1731, he married a woman named Smith. In 1734, his former apprentice, John Peter Zenger, was brought to court for libel, but Bradford remained neutral during the case.

Bradford retired at the age of 81 in 1744. He died on May 23, 1752 and was interred in the Trinity Churchyard Cemetery on Wall Street in Manhattan. wikipedia

Lower Manhattan continued to be the center of NYC’s printing industry for many years. The New York Times and New York Herald had their original offices on Park Row for decades; Ernst Plassman’s statue of Franklin, a printer by trade, stands on Park Row and Spruce Street, an intersection once called Printing House Square.

Several more of the historic 1830s buildings along Pearl Street. I’ve been in a couple of the taverns and eateries long the stretch including the Stone Street Tavern (its sign is reversed on the Pearl Street end) and Ulysses.

I have a question. Allow me to rant a bit.

We’ve had ForgottenTours in which we have staggered through the doors of one or more of these places on a Sunday around 3 PM, eager to be liquored and fed especially after 3 hours on a hot day. The liquor was plentiful enough, but we were told that the eats aren’t available at 3 PM and would have to wait an hour or two (I’ve run into this problem on Cortelyou Road, Brooklyn and a place called Indian Road in Inwood, too).

If you’re running a restaurant shouldn’t you have food available all the time? Or am I being a typical lowbrow consumer?

In one case we finished our drinks at the Stone Street Tavern and then repaired to George’s New York on Greenwich, where we were properly fed and watered. Any thoughts? kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com.

India House, Pearl Street and 1 Hanover Square, was constructed as the Hanover Bank from 1851-1853 by architect/carpenter Richard F. Carman, who later founded an uptown village called Carmansville. It’s a mini-Italianate Revival brownstone building with distinctive Corinthian columns and pilasters at the entrance. In 1914 it became the headquarters of the private club India House.

Two Type C posts have made their way to 1 Hanover Square. Type C’s were used in parks and boulevards, and were originally lit by gaslights. Other than these two, and several that have made their way to some lawns in the historic districts in Brooklyn south of Prospect Park, there are none left; the Type B “Henry Bacon” posts, designed by the architect of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, now appear in NYC parks by the thousands.

Hanover Square is a triangle/public plaza formed by Pearl and Stone Streets and the east-west street also called Hanover Square. The square and Hanover Street are a holdover from the British colonial era, since Hanover was the ruling family in Britain while George III was the British monarch. The family had originated in Germany.

In fact NYC has made this square the Queen Elizabeth II September 11th Garden, commemorating 67 British victims of the September 11, 2001, attack on the World Trade Center. It was officially opened on July 6, 2010 by QEII herself.

For several years, Hanover Square was the home of a massive statue of a seated Abraham De Peyster, a 17th Century NYC mayor; it had already been moved there from a prime spot at Bowling Green. Currently, DePeyster is residing in Thomas Paine Park near City Hall. Actually, De Peyster’s mansion was located on Pearl Street so it was fitting that he be remembered here, but the City had different ideas. A long gone alley Downtown was also named for him.

If the lower leg of the Second Avenue Subway is ever built, Hanover Square is scheduled to be the southernmost stop.

On the right is 10 Hanover Square, a 23-floor office building once home to Goldman Sachs; it was converted to residential/commercial in 2005. The building is one of my favorite sites because of what used to stand in front of it in recent memory…

A bishop crook streetlamp of elderly vintage, snapped here by Bob Mulero around 1980. (Sorry for the fuzzy blowup.) It’s shorter than most crooks, since it had to fit under an elevated train before 1942. It was also a crook with a different base and scrollwork design from the prevailing type; there were plenty of these on narrower streets.

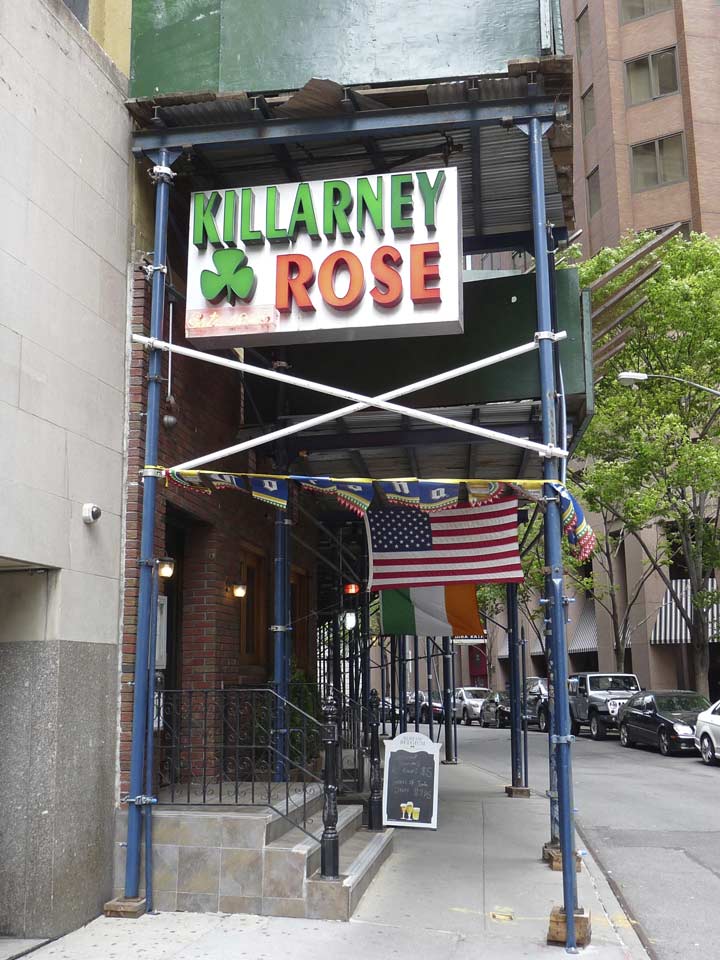

Killarney Rose has been serving beers, shots and the occasional lunch on Pearl Street since 1968, as the neon sign indicates. Ever-present scaffolding can’t completely obscure the sign. Killarney is a small town in County Kerry, Ireland. Its name is derived from an Irish Gaelic term meaning ‘church of sloes’, a sloe being a blackthorn plant from which a variety of gin is derived.

At #82-92 Beaver Street at its sharp junction with Pearl just south of Wall, is the Beaver Building, which began as the Munson Steamship Co. building and later the NY Cocoa Exchange Building, constructed in 1904, about the same time as the Flatiron. Recently it’s been given the odd address #1 Wall Street Court. It isn’t on Wall Street but in plain sight of it, and developers wanted to give it a cachet to attract residential buyers.

This round-arched building, #74 Wall Street at Pearl, was put up in 1926 as the Seamen’s Bank for Savings Headquarters (hence the seahorses, mermaids and other nautical motifs); the architect was Benjamin Wistar Morris, who designed both ends of the block of Wall between Pearl and William. The site was once the home of Edward Livingston, NYC mayor and US Secretary of State for Andrew Jackson.

In the Dutch colonial era, the corner of Wall and Pearl was an important one. This was that era’s “Water Gate” — an entry point at the wall that Wall Street was named for. At 9 PM sentries closed the gate, as well as others in the wall, and taverns closed at ten. Patrons still in the taverns were obliged to remain there all night until the signal came at sunrise to open the gates and allow street traffic again.

Jumping a head a couple of blocks — I find the glass towers somewhat boring — here’s an interesting curio at #211 Pearl Street at Fletcher… the front of a historic building constructed in 1831 for soap manufacturer William Colgate (the same Colgate of the current toothpaste brand and massive Jersey City clock). Odd symbols were also found incorporated into the design. When a huge tower went up behind it in the early 2000s it was scheduled for demolition (its partners, 213 and 215 Pearl, indeed were) but luckily, the facade was incorporated into a parking garage entrance. Small victories…

Sorry to say I’ve never eaten at the Pearl Diner — another surviving curio at Fletcher Street. Supposedly it’s been here since the swinging Sixties. It’s #11 on this list and has generally good reviews. The Pearl Diner at night.

Just a block south at Pearl and Maiden Lane, the first British tavern in the city, the King’s Head, was established by Roger Baker shortly after the British took New York in 1664.

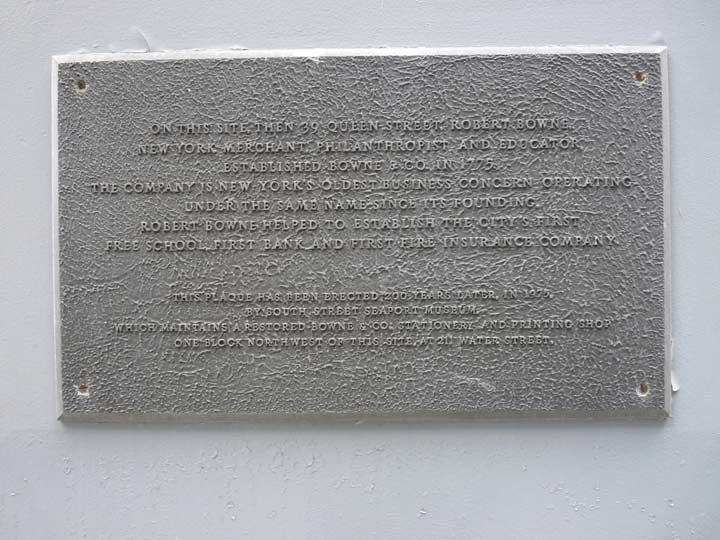

On the Pearl Street side of the 1969 glass tower 127 John Street between John and Fulton, we see this plaque that notes the founding of printers Robert Bowne & Co. in 1775. Bowne is still in business, just up ahead at Water and Fulton.

“I’d like to see what you look like/With a fish’s head and a human tail” — “Mermaid,” Jowe Head

Fanciful art on the Fulton Street side of 127 John.

Pearl Street does something rather odd at Fulton Street. It gains two more lanes as it takes over Water Street’s traffic. Yet, Water Street continues north on a separate route.

New York City has formal, informal and completely accidental homages to those who died in the sinking of the HMS Titanic on April 15, 1912. On the corner of Fulton and Pearl Streets stands a reminder of one of the world’s most infamous naval disasters. The Titanic Memorial Lighthouse was dedicated exactly one year after the sinking and was originally placed atop the Seamen’s Church Institute, a 14-story building at South Street and Coenties Slip downtown. In 1967 the Seamen’s Institute moved and the building was later demolished; the lighthouse, fortunately, was preserved and by 1976, had been installed at its present location. The tall pole at the apex originally had a metal ball that, when signaled by a telegraph at the National Observatory in Washington, DC, would drop at noon daily.

And here I thought the Seaport was supposed to look back on yesterday, not tomorrow…

The area surrounding and including the Seaport and its shops, museums and sailing vessels took a big hit from Hurricane Sandy in October 2012. Developers have swooped in — already Pier 17, which I found a good place for a cheap lunch, has been demolished and a much more upscale operation is under construction. What would Joseph Mitchell and the denizens he encountered here in the 1940s think?

I’ve always loved reading Mitchell, but my enjoyment is couched in envy, as are many of my enjoyments. Due to the indulgence of the editor of the New Yorker during his employment there, William Shawn, Mitchell went to his office every day after 1964 for nearly 30 years and never published another word, though he was … working on things.

The Southbridge Houses, which along with Beekman Downtown Hospital and the 1973 NYPD headquarters, took out an entire network of small downtown streets, looms now as we pass Fulton Street and move uptown.

This building on Water Street, seen from Pearl across a parking lot, was the last home of the Seaman’s Institute, which had moved from Coenties Slip to State Street in 1968 and then here.

Peck Slip, which still has its Belgian blocks, is one of the “slips” or former artificial inlets where boats were moored that dot the East River-front in Lower Manhattan.

Peck Slip, which runs through the heart of the landmarked seaport district from Pearl to South Streets, is the east end of the now-vanished Ferry Street, which fell victim to “urban renewal,” i.e. the Southbridge Towers. Benjamin Peck was a British merchant in pre-Revolutionary New York, and the Slip first appeared in 1755 at Peck’s market. The Slip was filled in by 1817. It’s not to be confused with Pike Slip, which is north of the Brooklyn Bridge.

In the colonial era, the 1660s, there was a ferry service at Pearl (which was then on the waterfront) and where Peck Slip would eventually be built. In those days, things were a little less sophisticated. A horn was tied to a tree near the spot and anyone needing a lift across the East River would blow on the horn, alerting the ferryman, Harmanus van Borsum, who was working his fields nearby. When weather allowed, for a guilder or two van Borsum would ferry people across to Breukelen.

Up ahead is 375 Pearl, the Verizon Tower, which some critics have called the ugliest building in NYC. As I note on this FNY page, I’ve seen a lot worse.

Coming in Part 3: past the Brooklyn Bridge and NYPD HQ

7/10/16

I must have messed up somewhere. kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com

Sources include: The Streets of Old New York, J. Ernest Brierly, Hastings House 1953

14 comments

Thank you so much for posting this. My father´s business was the G & H Bar & Grill at 121 Pearl Street. Wish I could find some information on it. I will head down and walk it tomorrow morning. Elisa

I lived at 120 Pearl from 1941 to 1960. We were in G & H many times.

Hi Kevin,

Thank you for sharing this fascinating 3-part narrative. I was directed to your piece while seeking information on the Castello Plan. I’m also going to look into the history of Coenties Slip and exactly how/why the island was landfilled. (Yes, I’m a NYC history newbie). Thanks again from an Arizonan.

Thanks for this Pearl Street tour! Question: There was an abolitionist bookstore on Pearl Street, run in the 1830s by Isaac T. Hopper. Do you know where it might have been?

My original Dutch ancestor – Christoffel Hooglandt (1634-1684) & family lived on Pearl St between Whitehall & State until his death in 1684. His widowed wife Catrina Cregier remarried in 1688 and sold the former home. What a treat to find your site ! NYC is such an important framework for the history of our country.

Great stories. I worked at 111 Wall St. from 1969-1976. Walked many of these streets during lunch and after work. Was fun to see some of the buildings that haven’t changed too much. Thanks.

My maternal great grandparents (both sets)were living

at 407 Pearl Street at the turn of the 19th Century.

my great grandfather named Carl Schroeder owned a tavern on pearl street with his other German brothers– years ago my grandmother had a photo of them all with handlebar mustaches standing outside the tavern– I think it was the Schroeder Tavern and I’m desperate to find information on this tavern. The photo is gone and all I have is a note from my grandmother Alice Schroeder saying her grandfather had this tavern on Pearl Street. I’d welcome any help on finding out about this tavern. He also owned a “summer hotel” in Mt Kisco (my grandmother said). He was born in 1874 and died at 50 years old…shot in the dark I know. Please reach out to me at TamaraStephenson1@gmail.com if you have any advice- I’d be greatly appreciative

Dear Kevin,

fascinating pictures and insights. Can I ask you a facor? I am interested in the site 264 Pearl Street – do you have any pictures or information on it? It used to be the adress of a company of the lubricant industry – L. Sonneborn Sons, from roughly 1902 until the end of the 1950s. Since I am currently on “the other side of the ocean” it would be great to receive a picture or a note as to whether any building has survived or any other trace of this company can be found. Best regards from Germany, Eva (pev@onlinehome.de)

Afraid I do not.

I have recently heard that there was Beal’s (Beel’s?) Free Store at 376 Pearl in the early 1800’s, where products not associated with slave labor, were sold. Ever hear of that?

Very interesting. It’s so hard to have a convincing picture of what NY used to look like, but your

photographs and notes are invaluable. Many thanks!

Are you saying the site at 6 Pearl Street where Melville was born has now no mention of this fact?

Does anyone have any information on 80 Pearl Street? I think its abandoned but I don’t know.