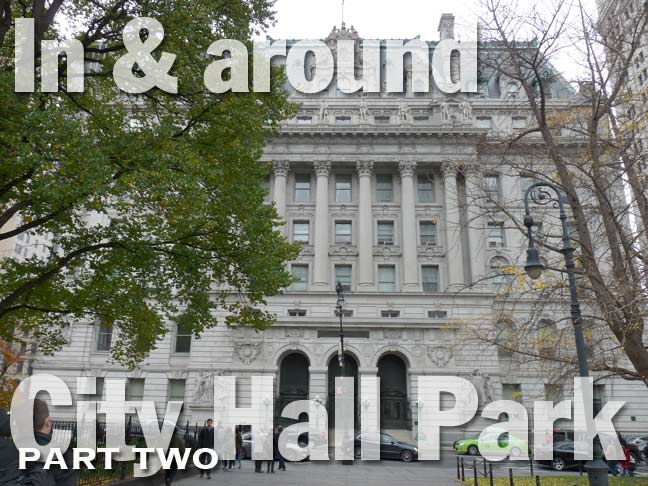

I decided to head over to City Hall Park, and the area immediately surrounding it, to look at the lampposts. But as usual with this stuff, it turned into something more.

A little history first. As with many of New York City’s parks south of 59th Street, the park had military connections in its early yearsand was used as a cemetery for awhile. During the Dutch colonial era it was a commons, or an area used for public recreation (as in the Boston Common). After the British took over in 1664, things took a darker turn. The first execution by hanging took place in the former commons in 1691, and the first almshouse (the medieval equivalent of a retirement home, though decidedly less pleasant) was built here in 1735. In the subsequent decades the British used the commons for military parades and in 1757 a prison was built on the grounds.

As the city gradually moved northward the commons also found public uses, including opposition to British rule. Between 1766 and 1770 five “Liberty poles,” erected in sympathy to the patriotic cause, were raised in the commons but all were soon torn down by the British troops and loyalists. During the Revolutionary War, prisoners of war were ensconced in the prison and an additional one called Bridewell (see below).

After the war was won, the commons again became a public area. The site was chosen for New York’s new City Hall in the first decade of the 19th Century, replacing an older one at Wall and Nassau Streets. The new City Hall was designed by Joseph Mangin and John McComb and opened in an area many considered far removed from NYC’s business district. In fact, cheaper materials were used for the facing in the rear of the building facing Chambers Street.

The southern end of the park was home to New York’s central post office between 1867 and 1910 in a building several critics of the period considered to be an ugly monstrosity; it was finally torn down in 1939, and the junction of Broadway and Park Row was again open to the air. It still is, though it’s one of Manhattan’s most crowded and horn-honkingest intersections.

At the end of Part 1, linked above, I had edged over to the park’s southern end to take a look at the revived 5 Beekman Street, or Temple Court, which had been neglected for years but has reblossomed as a hotel. It is on view temporarily from the park before another tower rises to block it once again.

One building on Park Row facing City Hall Park was one that I frequented quite a bit from the 1980s into the 2000s, and computer, hi-fi and recorded music enthusiasts will immediately recognize it…

J&R Music World held forth in several buildings from #17 through #34 on Park Row between Ann and Beekman Streets. J&R opened in 1971 at #33 by Joe and Rachelle Friedman, originally specializing in audio/video equipment before branching out. It had a huge music section, decent prices, and something of a reputation for brusqueness on the part of its salesmen and service people. Nevertheless, I was a fixture for several years picking through the record racks or scavenging through the computer software department in the days when most of it was written for the Windows platform and I scrounged what I could find for the Mac. I also purchased my first digital camera here.

In the late 1990s, there were various reference databases published by Microsoft, and some, like Encarta, an encyclopedia. or another movies database (I forget its name) they deigned to release for the Mac. Others, like their baseball reference software, weren’t. Today, such stuff has moved over to the internet and is accessible for all.

J&R succumbed like Tower, Circuit City, Sam Goody and most other mass market electronics and record stores. Its final day was in April, 2014.

In December 2016 there were two remnants at #1 Park Row left: on the corner of Ann, the company logo embedded in the sidewalk and another one on the building’s cornice.

The demolition of a building on the SE corner of Park Row and Beekman Street has permitted the temporary exposure of Theater Alley… or would, if the protective sheds from surrounding construction were ever removed. Theatre Alley has been in existence for at least 175 years, but it seems as if it has been closed or rendered not navigable for almost as long.

I last wrote about the alley in 2007:

Theatre Alley, running from Ann to Beekman just east of Park Row, at one time was the back entrance to the old Park Theatre(originally the New Theatre), which fronted on Park Row. It stood from 1798 to 1820; after a fire the theatre was rebuilt the next year, and stood till 1848, when it once again burned down. At that time the Park Theatre was beginning to lose out to other theaters springing up along the Bowery uptown. The Astors, who owned it then, elected to not rebuild it.

John Howard Payne, composer of “Home, Sweet Home” was a frequent performer at the Park as a dramatic actor, as was Edmund Kean and his son Charles Kean, Junius Brutus Booth (father of famed actor Edwin Booth and Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth) and Tyrone Power (1795-1841), an antecedent of the famed screen actor of the 1930s and 1940s. Charles Dickens was feted at the Park on a visit to New York in 1842.

Today Theatre Alley is nondescript and usually covered by scaffolding; I happened by on a day when the usual scaffolds had been removed, looking north from Ann Street. For several years a curious stencil has appeared on a building wall near Beekman advertising the Victoria Theatre, with “vaudeville’ and “photoplays” added. It’s just an art project, originally done for a movie shoot, since there was never a Victoria Theatre here, and certainly never a movie theater. The stencil is reminiscent of the old marquee for Variety Photoplays on 3rd Avenue and East 13th, razed in 2005. Mapping Theatre Alley

Some things never change! The scaffolding is still there, but the building with the “Variety Photoplays” stecilling has been razed.

Looking south on Park Row to Broadway is the oldest remaining church building in Manhattan, St. Paul’s Chapel (1766) where George Washington worshipped and H.P.Lovecraft got married. Washington’s pew is marked — it dates back to the days when church pews had to be rented or bought. St. Paul’s has always been associated with Trinity Church, founded in the late 1600s; many streets in lower Manhattan are named for Trinity Church vestrymen. I’ve only been inside once and gotten only a couple of pictures, but in 2013 I did spend some time in the churchyard. After the 2001 terrorist attacks, the church, which suffered little damage, served as a meeting place for relief and construction workers and a place of solace for New Yorkers.

Returning to City Hall Park proper, I found the Jacob Wrey Mould Fountain’s gaslights and water jets unfortunately turned off, but they’re a great sight when actually working.

City Hall Park has boasted two fountains during its existence; the first was installed in 1842 and had a 100-foot diameter basin with 50-foot water jets, with the water pumped downtown from the Croton Aqueduct. The second, the Mould fountain, was installed in 1871 and is reminiscent of his much larger Bethesda Fountain in Central Park.

In 1920, the Mould fountain was shipped off to Crotona Park in the Bronx in favor of Frederick MacMonnies’ controversial Civic Virtue, which depicted a Herculean figure representing Virtue astride two writing mermaids representing Vice. Fiorello LaGuardia didn’t like seeing it out of his City Hall office window and had “Fat Boy” moved out to a spot near Queens Boro Hall (in 2012 another group of politicians, including of all people, Anthony Weiner, argued for its removal from that location because of its perceived misogyny. A restored Civic Virtue now sits in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery).

The fountain was rehabilitated and returned to City Hall Park during renovations in the late 1990s.

Tom Miller, Daytonian in Manhattan, gave the fountain its due.

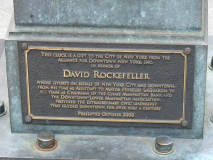

The City Hall Park Clock, installed in 2000, stands at the southern tip of the park at Broadway and Park Row, where the old Post Office stood many years ago. Manufacturer Canterbury Designs based the design on street clocks built by E. W. Howard and first installed in British towns from 1850 to 1920. It was dedicated to Chase Bank chairman David Rockefeller (b. 1915).

I’ve never been able to get a photo of Nathan Hale’s face. That’s because his statue stands in an area closed to the public since the late 1990s, when extra security was installed in City Hall Park and the area surrounding the building was cordoned off. It didn’t prevent a murder in City Hall in 2003, however.

The name Nathan Hale is synonymous with American patriotism. A volunteer for a dangerous spy mission in enemy territory on Manhattan Island during the Revolution, the young officer carried several incriminating reports, including his Yale diploma, when he was captured by the British and summarily executed. Many historians now agree that he did not utter the famous line, “I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country” before his hanging. Hale, according to some accounts, was executed at what is the present corner of East Broadway and Market Street on an apple tree in Henry Rutgers’ farm, though in other renderings he was killed near what is now the United Nations complex.

Hale is the second youngest person memorialized by a statue in Manhattan; Joan of Arc is the youngest.

The heroic sculpture, by Frederick MacMonnies of Civic Virtue (in)fam(y), was installed in 1903, with the pedestal designed by Stanford White, himself a murder victim.

Is it time to move Nathan Hale to the public section of City Hall Park? kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com

Several buildings surrounding City Hall Park seem to be the apotheosis of the Beaux Arts architecture period, when more of everything was better — more sculptures, more paintings, more ornamentation, more statuary — in an era when it was believed that great wealth was conferred upon great people.

The NYC Surrogates’ Court, 31 Chambers Street, also known as the Hall of Records — is where NYC’s Municipal Archives are maintained. It was built from 1901-1907 and designed by John Thomas and the architects Hogan and Slattery. 54 allegorical sculptures representing “New York in Its Infancy,” “New York in Revolutionary Times,” Philosophy, Law, and the seasons appear on the exterior along with almost forgotten eminences from the city’s past such as New Amsterdam Director General Peter Stuyvesant; De Witt Clinton, who held most important NYS elected positions; mayors Caleb Heathcoate, Abram Stevens Hewitt, Philip Hone, Cadwallader Colden, and James Duane, among others.

If you ever get a chance to go inside, do so, since the interior, featuring a 3-story courtyard inspired by the Paris Opera House, mosaic murals of the zodiac, and carved oak and mahogany courtrooms are considered among the finest Beaux Arts interiors to be found anywhere.

The Surrogates’ Court hears cases involving the affairs of decedents such as wills and estates. Meanwhile, there are photographs from NYC’s Municipal Archives online (albeit with a prominent watermark).

Some of the ancient records are due to be moved elsewhere [NY Times]

NYC’s Municipal Building stands across from City Hall Park just north of the Brooklyn Bridge entrance at Centre and Chambers Streets. It was constructed in 1914 from plans by the firm of McKim, Mead and White. It was built with a trafficway allowing Chambers Street to pass right through it; when the new NYC Police department headquarters was built in the 1980s, the trafficway was closed off.

The sculptures on the north arch include allegorical representations of Progress, Civic Duty, Guidance, Executive Power, Civic Pride and Prudence. Between the windows on the second floor are symbols of various city departments. Note the collection of plaques, among which is the “triple X” emblem of Amsterdam, Holland. Chambers Street once passed through the building and once went all the way to Chatham Square but the NYC Police Dept complex was built over its path in the 1960s. Gerard Wolfe

The building’s most famed component is probably the 25-foot tall gilded Civic Fame representative statue at the colonnaded tower at its apex.

In October 2006 I traveled to this building to appear in a 15-minute segment with WNYC’s Brian Lehrer in which I fielded his questions and some from the listening audience. Later that day Forgotten NY The Book reached its highest sales position in the Amazon charts, almost to the top 500. The WNYC studio has since moved to 160 Varick Street.

Horace Greeley merits not one but two statues in NYC in areas open to the public (well, in the case of City Hall Park, just about). This Horace was sculpted by John Quincy Adams Ward (the pedestal is by Richard Morris Hunt, who also designed Lady Liberty’s pedestal) in 1890 and originally stood in front of the old NY Tribune newspaper building on Park Row; journalist Greeley had founded the Tribune in 1841 as the voice of the Whig political party.

There was actually a 1915 ordinance whose purpose was to rid the city of “street appurtenances”, i.e. nonessential objects, and so this Greeley was moved to City Hall Park that year. The other Greeley is found in Greeley Square at 6th Avenue, Broadway and West 33rd Street.

A reformer, Greeley opposed slavery and promoted the rights of factory workers and the unemployed at a time when such sentiments were far from universally accepted. He was once caned by a US Representative from Arkansas, Albert Rust, for opposing Rust’s pro-slavery stance.

After a lifetime in journalism, Greeley, a Whig and later a Republican, was nominated as the Democratic candidate for President in 1872. He was trounced by Ulysses S. Grant and died a month after the election.

Though it’s likely he didn’t utter his most famous line, “Go west, young man”, he did write:

“Do not lounge in the cities! There is room and health in the country, away from the crowds of idlers and imbeciles. Go west, before you are fitted for no life but that of the factory.” (New York Tribune, 1841)

In 1924 the Tribune was merged with the New York Herald to form the New York Herald Tribune, which ceased publication in 1966.

Canadian architect Frank Gehry‘s (1929- ) undulating or crumpled building designs can be an acquired taste for some. I do like his 8 Spruce Street, for a time NYC’s tallest residential building, which can be clearly seen from City Hall Park on Centre Street looking south. It is 76 stories and 870 feet tall, with a wavy exterior of reinforced concrete. It contains a public elementary school and opened in 2011.

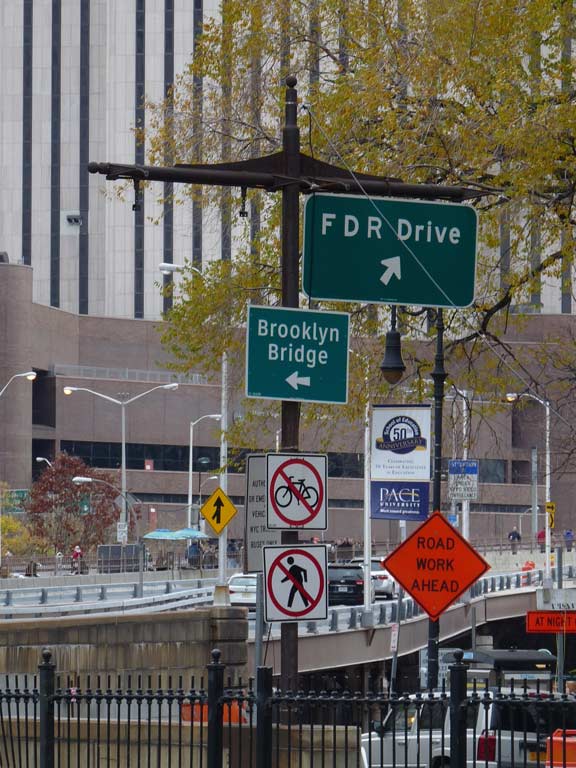

Here are some City Hall Park area survivors: this iron signpost has been here on the Brooklyn Bridge approach ramps since the 1950s, at least. The finned supports are also a hallmark of the T-shaped Whitestone Bridge lampposts, which have largely disappeared but once lit NYC expressways and parkways by the thousands. These posts are quite heavy and can withstand wear and tear.

City Hall Park was an early adopter of electric streetlights, which first appeared in 1903. Some where Bishop Crook lamps, which began appearing in abundance in the 1910s. There are also some varieties that aren’t seen on city streets in any numbers seen here as well.

This number is a Type 24 A-W. The scrollwork on the apices is simpler in execution and was made of wrought iron instead of cast iron. They likely appeared in the early 1940s when more expensive iron materials were needed for WWII materials used in combat.

Now-rare Type 1BCs can also be seen in the park. They are recognizable by thinner shafts with a wrapping garland motif, a ladder rest crossbar harking back to the gaslamp era, and the lightbulb symbol of the Edison company on the base.

During park renovations in the 1990s, these lamps were repainted, given a new Bell luminaire with bright yellow sodium bulbs, and a new fixture with a bulb motif reminiscent of the early, more ornamented days of NYC street lighting.

1/2/17