I was on the far West End of Manhattan recently on the border of the Meatpacking District and Chelsea, at 9th and West 14th, asking about my IPhone battery at the Apple store there (where I have to go now, instead of the much more convenient Tekserve, which went out of business, death by landlord and rising rents). The battery drains al of a sudden on occasion, and the solutions aren’t exactly palatable; it involves backing up the phone, deleting all the apps, and putting them back one by one until I figure out which one is causing the drain. Whatta mess. Maybe I’ll just save a bit and get a new battery.

Anyway, I took a brief walk from there back to Penn Station and, once again, was fascinated by all the infrastructure. I took a walk through Chelsea Market for the first time in a decade, and found the crowds oppressive; that’s a new hallmark of the neighborhood which has become a tourist haven.

Washington and Gansevoort Streets, November 2016

I have visited and chronicled the Meatpacking District often, beginning in 2006, came back in 2009, 2013 and other times. The former freight railroad, the High Line, first came under FNY scrutiny before it was ever opened as a park, starting in 1999:

… and finally, its last section that opened in 2014.

I continue to have a fascination with the Meatpacking District and the High Line that runs north into Chelsea and ends at West 34th Street. I gather that the “linear park” hasn’t gone the route that its creators had envisioned; it has become a tourist conveyor belt, more or less, and is apparently rarely visited by neighborhood residents and New Yorkers. What’s more, it has driven up property values — normally a favorable result — but skyrocketed them, pushing out small businesses like mom and pops, barber shops, bodegas and gas stations, and gave rise to pricey condos, many of them behemoths.

I get all this. But, I cannot turn away and completely badmouth the High Line. In the end, Forgotten NY is an infrastructure website, and I’ve been fascinated and yes, even gratified by how a former elevated freight train trestle — one that the Giuliani administration was hot to tear down 20 years ago — has been resuscitated and revived, though I wish it could have become a western extension of the #7 Flushing Line.

This page will use some images captured in a November 2016 walk through these parts, as more as the more recent October 2017 jaunt. There are still some meatpackers in The Meatpacking, though some have to be rooted out and some are hiding in plain sight such as these along Washington Street between Gansevoort and Little West 12th Street, Louis Zucker ands J.T. Jobbagy.

The survivors, listed by the amount of space they rent in the building, are Interstate Food Inc., Weichsel Beef Inc., J.T. Jobbagy Inc., London Meat Corp., John W. Williams Meat Corp., Louis Zucker & Co. and Highline Meat Co. With so few remaining, the meatpackers are much less competitive with each other than the cutthroat days of yesteryear. Jobbagy focuses on steaks for restaurants, while a neighbor emphasizes retailers. Another dealer specializes in lamb and another in poultry, so people aren’t stepping on each other’s toes much.

At its peak in the 1950s, the meatpacking district consisted of 200 companies that employed 3,000 butchers and wholesalers. The market stretched south from 14th Street to Horatio Street and from Ninth Avenue west to the Hudson. “It was nuts,” recalled Robert Greenzeig, president of Interstate Food, who has worked in the market for 38 years. “Trucks all over the place, action all the time; it was a sight.”

The smell was something to experience, too. New Yorkers of a certain age will never forget the stench of veal hides sweating in the sun or cow blood flowing in the streets. The market was also a place where renowned New York prosecutors like Frank Hogan and Robert Morgenthau made their reputations cracking down on mob activity. [Crain’s New York Business]

The remaining meatpackers in the neighborhood received a favorable lease, which runs through 2032, by ceding to the city a portion of their property that was used to build the new Whitney Museum on Gansevoort between Washington and West Streets; the firms are consolidated in a coop called Gansevoort Market. The Whitney family who founded the museum are the same Whitneys who built a mansion and raised thoroughbred horses in eastern Gravesend, Brooklyn that I explored with this FNY series; NYC is interconnected in myriads of ways.

At this writing I have not yet eaten at Meatpacking survivor Hector’s Cafe (which has been here since 1949), at Washington and Little West 12th. That’s a shame because when I first wrote about the place in 2013, I hadn’t yet been in, either. NYC loses more diners every year; I’ve since closed the Market Diner, the Del Rio and the Vegas in Brooklyn, and had already bid farewell to the Scobee in Queens and the Cheyenne in Midtown. What am I waiting for? The prices remain quite affordable compared to the other high-concept and haute cuisine places that have sprung up in this neighborhood.

John W. Williams, Weichsel and London Beef wholesalers, south side of Little West 12th between Washington and West Streets.

Newsday has provided a handy Meatpacking area chronology:

1851: The city acquires Astor family property, underwater and off Gansevoort Street, to consolidate downtown markets.

1884: Market opens between Gansevoort and Little West 12th streets.

1887: Meat and poultry are added to the district with the West Washington Market.

1900: About 250 meat plants and slaughterhouses thrive in the area.

1934: High Line is completed, originally going as far south as Canal Street.

1949: City builds Gansevoort Meat Market co-op, which survives.

1970s: Club goers mix with meatpackers overnight as a dance, drug and sex scene emerges in the neighborhood.

Late 1970s: Manhattan Storage Warehouse converted to West Coast apartments.

1985: Renowned gay club Mineshaft is shuttered.

1985: Florent restaurant opens, popular with club kids.

Late 1990s: Jeffrey New York leads the way for the arrival of high-end clothing boutiques.

1997: Chelsea Market, built in a former Oreo cookie factory, opens.

1999: Restaurateur Keith McNally opens Pastis restaurant.

2001: About 36 meatpackers remain in the area.

2003: Part of neighborhood is landmarked.

2004: New York magazine declares it the city’s “most fashionable neighborhood.”

2007: Apple’s MePa [yikes — ed.] store opens.

2008: Whitney Museum announces plans for a MePa annex. Florent closes.

2009: First part of High Line park opens. About eight meatpackers remain.

Brass Monkey, 55 Little West 12th, occupies a former meat processing plant built in the early 20th Century. Featuring 3 separate bars, its draw is Guinness but it offers over 100 domestic and imported beers along with affordable bar-type food. The Standard Hotel looms in the background. It was completed in 2009 and straddles the High Line. Its toilets face the windows and guests using them have been visible to High Line walkers.

The iron archway over Pier 54 is the last remnant of what was once a large brick terminal building serving the White Star line of luxury passenger ships that included the Titanic, which would have berthed nearby on Pier 58 had an iceberg not sunk it on April 15, 1912 in the north Atlantic Ocean.

“Samsung 837” Washington Street, built on the shell of the old meat market that used to stand there, is a glimmering residential tower, featuring a Gehry-ish torqued facade. As a nod to the meatpackers, the old tin awnings and defunct meat racks will continue to be displayed above the sidewalk. The building is a de facto museum of Samsung, the electronics company, though no Samsung products are sold there.

As another nod to the meatpackers the side entrance, 426 West 13th, still bears its old “Super City Meat” sign.

Only one small sign on the West 13th Street side of 857 Washington Street marks the place where legendary dive bar Hogs & Heifers, serving both the meatpacking and biker crowds between 1992 and 2015. A rent hike to $60,000 per month forced out the popular joint. The bartenders and female patrons, who were encouraged to remove their bras and donate them to the rafters, danced on the bar and drink orders were yelled through bullhorns. Sedate retailers occupy the corner of the venerable century-old brick building, itself once home to meat wholesalers.

A quick trip up the staircase to the High Line itself reveals this scene. Though it’s carefully curated, it appears to be a scene in which the former railroad tracks have been returned to nature by windblown seeds giving rise to trees. That was indeed the situation from 1980 to 2008 when the old railroad lay fallow. These birches, however, are carefully nurtured by park personnel.

Skipping north to 10th Avenue, the High Line crosses it at an angle at West 16th Street. As FNY readers know I’ve always been fascinated at how NYC handles street lighting on overpasses. The High Line (originally the West Side Freight Railroad), built in 1934, at intervals employs S-curved stanchions to light the streets beneath. In addition to the stoplights mounted on the trestle, in recent years the stanchion has received a “Stad” luminaire as shown in the DOT streetlighting manual. Surrounding streets have received freestanding davit lampposts employing the same fixture.

Also note the exposed rivets in the High Line, a hallmark of the structure.

When first built the High Line was a freight railroad (though photos exist of fantrips using passenger cars on the trestle). At 10th and 16th, two now dead-end spurs enter factories. Goods were loaded directly from platforms located in these buildings onto the tracks, which originally ended downtown at St. John’s Terminal near Canal Street, where a transfer facility placed them on boats entering the Hudson River.

The High Line at #99 10th Avenue at West 17th Street. This is the home of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s NYC office; there are holding cells in the building. The building takes up an entire square block and also is home to a storage company.

The massive structure was once a refrigerated warehouse used to store dairy, meat, seafood and produce for the Merchant Refrigerating Company.

The branch of Artichoke Basile Pizza at 114 10th Avenue at the NE corner of West 17th has a nifty neon sign, but I’m more interested in the pair of painstakingly chiseled street signs on the corner. They are exquisite. Look at that reverse serif on the t in th. Both signs have the Period of Importance that was common on signs up to 1915 or 1920. The New York Times. kept its own on the masthead until the 1960s, and The Wall Street Journal. still has its Period.

The pizzeria used to be Red Rock West, a biker bar with sexy bartenders a la Hogs & Heifers.

Infrastructure is my beat and I’m quite pleased with what the designers of the new High Line (James Corner Field Operations (Project Lead), Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Piet Oudolf) did here as it crosses 10th Avenue at West 17th, a window looking north on 10th Avenue with amphitheater-like seating behind it.

The story of how it was done is here:

The 10th Avenue Square is formed by the High Line’s dramatic crossing over 10th Avenue. When originally constructed, large, oversized steel girders were required to allow the structure to span over 10th Avenue. Given the depth of the steel girders, the architects proposed to cut down into the High Line deck and create an amphitheater. Openings were made in the steel webbing to create cutout windows with a view up Tenth Avenue. [Friends of the High Line]

The Department of Transportation has chipped in with design elements of its own, besides the davit lampposts referenced above. Note that the pedestrian crossing signals, stoplight stanchions and other “street furniture” are painted the same shade of gray-black as the High Line trestle itself.

“The Park” restaurant on 10th between West 17th and 18th is located in a former parking garage, and still employs the neon sign that inspired the name. Coincidentally, Avenue New York is next door.

A pair of former stables, #461 and #463 West 19th Street off 10th Avenue, both going back to 1880 at least, have survived fairly intact from when Berenice Abbott photographed them in 1938. Daytonian in Manhattan has details.

This pair of condo buildings, featuring slightly slanted windows straddling the High Liner were designed by Danish architect Thomas Juul-Hansen. Curbed has some interior photos. The site was formerly home to a one-story truck leasing shop. A duplex sells at the bargain price of $19M.

10th Avenue between West 20th and 21st Street forms the west end of the General Theological Society.

Architect George Coolidge Haight designed and built the various Gothic Revival buildings, including the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, between 1883 and 1902. The Seminary grounds had been an apple orchard owned by Clement Clarke Moore, an academician who was Professor of Oriental and Greek Literature, as well as Divinity and Biblical Learning at the General Theological Seminary; Moore donated part of his property to the Seminary. Moore anonymously published the holiday poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” in a Troy, NY newspaper in 1823; he did not publish it with a byline until 1844. Moore’s depiction of Santa Claus in the poem, combined with Thomas Nast’s depictions, helped to solidify The Jolly One’s present image.

The God of Commerce, however, has come to the GTS, which has been selling off its holdings for years. The High Line Hotel at 180 10th Avenue opened in 2013.

We know there will be a lobby coffee bar with the incredibly unpretentious name Intelligentsia (the Chicago brand’s first East Coast outpost). Later this summer, the front courtyard will get a makeover as a cafe, while the backyard is reserved for “bespoke cocktailing and dining.” [Curbed]

Church of the Guardian Angel, 193 10th Avenue at West 21st Street, once again across from the General Theological Seminary. The parish originated on West 23rd Street in 1888. The original church had to be torn down in the early 1930s to make way for the West Side Elevated Freight Railroad, today’s High Line. The New York Central Railroad, therefore, funded this new Sicilian Romanesque church that was completed in 1930. Lavish bas reliefs on the 10th Avenue side depict the life of Christ.

A trio of landmarked beauties at West 21st and 10th, part of the Chelsea Landmarked District:

From 1970’s LPC report.

I headed east from here, but I always check to see if there are still a couple of Westinghouse “cuplights” with their incandescent bulbs still working, under a spur of the High Line at West 30th Street and 10th Avenue. I really hope the city keeps these but they will probably give way to LED lighting soon.

A doorway at #445 West 21st, between 9th and 10th, built in 1899. When I served at Macy’s from 2000-2004, I would often walk south into Chelsea and take in all the architecture.

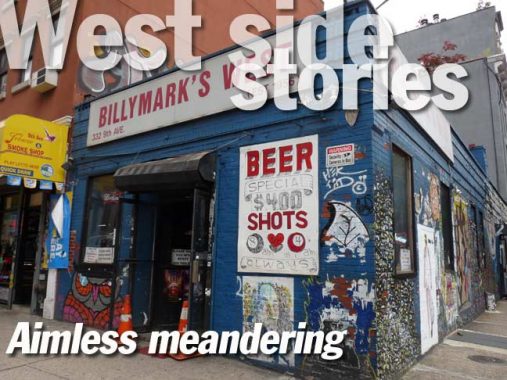

Surviving dive, Billymark’s West, 9th Avenue and West 29th Street. Google Street View lets you walk right in, sit right down. The bar first opened in 1956, but brothers Billy and Mark Penza have been operating it since 1999. Mark Penza, a sessions drummer, has appeared on platinum albums from the likes of Blondie.

This is the entrance to a parking garage at the James Farley Post Office, which is presently being reconfigured as the long-delayed Moynihan Train Hall, scheduled to open in 2020. It will be a western extension of the basement Penn Station; its hallmark will be skylights that will let sun in a la the old Penn Station (1910-1963). Hopefully the stonework and wonderfully verdigris’ed copper lamp sconce will be left in place.

After nine years, the condo building that replaced the Cheyenne Diner on 9th Avenue and West 33rd Street is finally taking shape.

In anticipation of the Moynihan Train Hall, a new Penn Station entrance and underground concourse have opened at 8th Avenue and West 31st.

A new modern art sculpture has popped up outside the entrance. I can’t make out the signature.

Let me ask a question. Most pieces of public art that appear in plazas now look like this, i.e., nothing. Why not bring back portrait sculpture for public plazas? How about boxer Joe Louis, the “Brown Bomber” for whom the Penn Station exterior plazas is named?

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

10/22/17