Pickings have been slim this winter for Forgotten New Yorking. I haven’t been able to get out much. Despite what I’m told was a monster flu season, with half the population laid up at some time over the past three months, I have felt perfectly well (I did get a flu shot in September). No, various obligations combined with iffy weather have kept me in. As stated on a previous page, I hate doing this in the rain, but I also don’t enjoy it with heavy winds, and I have had trouble getting free on days when conditions were optimum.

Now and then a sliver of opportunity presents itself, though, and on a February weekday I spent a couple of hours plunging into the East Village. This is not meant to be a comprehensive look at Alphabet City. I decided to concentrate on East 7th Street, which begins at Cooper Square and runs east to the Jacob Riis Houses at Avenue D. (Previously, I explored St. Mark’s Place, a block to the north, when Sounds and the Yaffa Cafe were still open.)

The East Village, much of it originally a part of the Stuyvesant family farm, has been a redoubt of German, Polish and Ukrainian immigration over the decades, and Loisaida (the region between Avenues A and D) has been New York City’s chief downtown Hispanic enclave. Gentrification has robbed it of much of its old flavor, but also a great deal of its old crime. That’s a tradeoff that urban strategists will have to debate. Me, I just shuffle around and take photos, trying to be unnoticed.

Picking up where we left off on East 7th east from 2nd Avenue…

GOOGLE MAP: EAST VILLAGE – EAST 7th

The handsome twin-spired, arch-entranced building at #50 East 7th is the “side entrance” of the Middle Collegiate Church (the front entrance was shown in Part 1). It is one of the oldest Protestant congregations in NYC, having been organized in 1628 — just two or three years after New Amsterdam itself was founded. In all that time it has had three church buildings: 1729-1838 on Nassau Street; 1839-1891 on Lafayette Street; and since 1892, in the East Village. The Church prides itself on its progressive political stances.

This is a particularly handsome architectural block; these are #66 and #68. East 7th Street is within the East Village-Lower East Side Historic District, and so we find that a good 60 years separates these two buildings, with #68 going up in 1837 with an 1882 alteration while the taller #66 dates to 1897. According to NY Songlines, the block was once lined with cafes and meeting halls that attracted the likes of Tuli Kupferberg of The Fugs, Yoko Ono, Loudon Wainwright III and William F. Buckley.

I first read this sign as Klimax but in fact it is Klimat at lucky #77 East 7th, a Polish-Czech bar with an Eastern European beer and cocktail selection.

The Blue & Gold Tavern next door has Ukrainian roots (blue and gold are the colors of the Ukrainian flag) and has been here in one form or the other since 1958. Besides drinking there’s Scrabble, backgammon and a pool table. It’s a dive bar’s dive bar in a neighborhood that doesn’t have quite as many as it did. The Blue & Gold prides itself on its low prices. It earned first place in the first edition of New York City’s Best Dive Bars (Wendy Mitchell, IG Publishing, 2003)

I could not resist heading a block north to St. Mark’s Place at 1st Avenue and a slice for lunch at Stromboli. I don’t think the slices are as robust as they used to be, but on this day the service was friendly and immediate. It’s across the street from Lorcan Otway’s Theatre 80, a former speakeasy which has a mini-Grauman’s of Hollywood stars’ handprints in concrete. On the second floor Otway runs the Mafia Museum.

Jim Power’s mosaic installation on the lamppost at 1st and St. Mark’s Place has a gangster theme — the Mafia Museum is a few doors down. It also recalls the 2007 film American Gangster featuring Denzel Washington as a gang lord beloved by his family and feared by everyone else.

Longtime East Village mainstay, clothing store Trash & Vaudeville, was founded at #4 St.Mark’s Place off Cooper Square by Ray Goodman in the summer of 1975. After a rent increase to $45,000 Goodman decided to move to 96 East 7th Street in early 2016.

Soon [after opening] Mr. Goodman found himself not only connected to the music he loved but also dressing its stars. Joey Ramone came around with his mother — “she was just the nicest” — looking for pants to fit his willowy 6-foot-5 frame.

Prince would visit. “He would just point,” Mr. Goodman said. “He wasn’t really speaking at that point. He would just point and you would get it down.” [NY Times]

The East Village is multifaceted. On the same block is St. Stanislaus Roman Catholic Church, #107 East 7th, dedicated in 1901. It has an almost all-Polish congregation, evidenced by its sign. Next door, #109 was constructed at about the same time and has been used as a rectory for the parish priests and then a convent for the nuns teaching at the school associated with the church. It looks like it hasn’t been renovated for a few years; the church is undergoing.

At #111 East 7th is the McKinley, an apartment building constructed in 1901 when William McKinley was President. Unusually for an apartment house, a Todd Hase furniture store leases the ground floor. If we look at an aerial shot, note that the rear of the building is constructed along a slant. In 1901, the builders had to construct the building along still-existing farm plots, hence the irregularity!

Another smallish church on the block at #121, St. Mary’s American Orthodox Greek Orthodox Church, was constructed in 1904 as the Hungarian Reformed Church [Frederick Ebeling, arch.] Its original brick facing was replaced by “Naturestone” in 1961, when the current congregation moved in. Since it must look nothing like it did when it was first built, don’t buy the usual blather from the LPC about a non-landmarking decision because the building was altered!

Tompkins Square

Like many other New York City public squares, Tompkins Square Park was originally used as a place where military commanders could review troops marching in formation, in this case the 7th Regiment, as you need a wide, flat space for that. Between 1836 and 1850, what had been a swampy and unstable area was gradually graded and landscaped, with some sycamore trees planted (most were chopped down when the Regiment arrived in the 1860s but some, on the outer edge of the park, survive). The park did not become a public area until 1878; like many other NYC locales and streets, it was named for NYS Governor, then Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins, who was from staten Island; he is buried in St. Mark’s churchyard, a couple of blocks away.

In the 1950s and 1960s, there was a gradual deterioration in NYC’s public spaces, as funds dried up and there was a general attitude on the part of our representatives for deferred maintenance. Everything came to a head in the summer of 1988, when the Koch Administration decided to forcibly oust the drug dealers and homeless that had largely “occupied” the park, and a riot ensued. The necessity of the force used by the NYPD is debated to this day, but the cleanup was the first shot in the battle between the longtime residents of the East Village and gentrifiers, who have gained the upper hand in the nearly 30 years since the so-called Tompkins Square Riots.

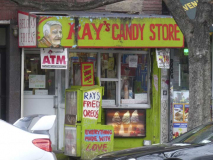

A pair of Avenue A mainstays facing the park between East 7th and St. Mark’s. Ray Alvarez (1933- ) has operated Ray’s Candy Store since 1974 and has gradually expanded the menu to serve parkgoers, featuring comfort food like ice cream, hotdogs, and the like. Ukrainian restaurant Odessa has been an East Village fixture since 1965; the restaurant survives, but the bar closed in 2013.

Louise Lawson’s sculpture of Ohio Congressman Samuel Sullivan Cox has stood at Tompkins Square’s southwest corner at Avenue A and East 7th Street since 1924, after its initial placement at the triangle formed by Lafayette Street, 4th Avenue, and Astor Place in 1881. S.S. Cox (1824-1889) was a Democratic Party member of the House of Representatives from Ohio from 1857-1865, and from New York from 1869-1889, when he retired. He championed the Life Saving Service, which patrolled the coast looking for shipwreck survivors; the Service became part of the US Coast Guard in 1915.

He is remembered with a statue, placed while he was still in Congress, for his involvement with the US Post Office. He introduced legislation that assured paid benefits, 2 weeks’ vacation, and a 40-hour work week—progressive in that era—for postal workers. Letter carriers from 188 cities inscribed on the monument raised $10,000 for its creation.

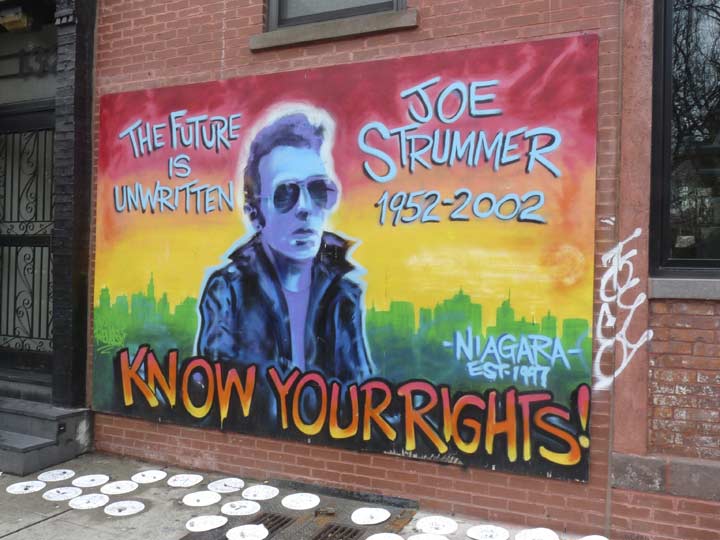

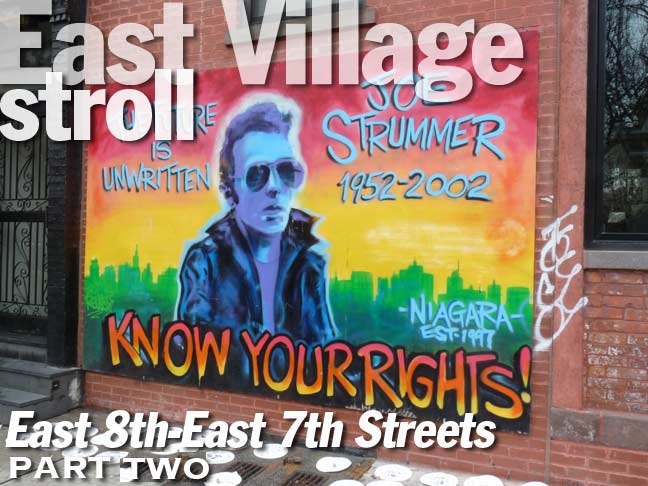

Cox’ statue stands across the street from a likeness of a man from a completely different place and time. John Mellor, known professionally as Joe Strummer (1952-2002), was the founder of “The Only Band That Matters,” the Clash. Of British parentage, he was born in Ankara, Turkey, as his father Ronald served in the British foreign service.

The Clash was of the most overtly political, explosive, and exciting bands of the late ’70s and early ’80s, with their music taking on Nazism, racism, unemployment, and police brutality. They achieved success in the US with the double LP London Calling and singles such as “Train in Vain” and “Rock the Casbah,” but their chief legacy was as a killer live act—they played the old, non-air-conditioned Bonds clothing store in Times Square for 17 straight days in June 1981, one of which I attended, though I know people who were at all of them. After the Clash’s breakup, Strummer did solo work and also played with the Pogues and the Mescaleros. He died of heart failure at age 50, but his legacy remains his huge heart.

The artwork here at Avenue A and East 7th Street was originally painted outside the Niagara, a bar Strummer frequented, in 2003, several months after his death, by graffiti artists Dr. Revolt and Zephyr. When the wall was in danger of collapse and had to be replaced in 2013, the artists were called back in to create a new mural. The artists renew the memorial every so often.

In 1988, the Christodora House on Avenue B and East 9th was the focal point for what longtime East Village residents saw as a battle between the status quo with affordable rents and a future of the rich moving in and pushing them out, as it was one of the first buildings in the area to be redeveloped as a condominium. It had been built in 1928 as a settlement house and had been used by community groups until that time, providing food, shelter, medical treatment and education to nearly 5,000 locals every week. It had a third floor concert space where George Gershwin gave one of his first public recitals.

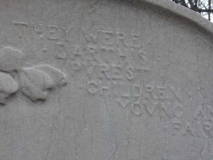

In 1906, a 9-foot tall monument to the victims of the June 15, 1904 General Slocum steamboat disaster in which over 1,000 people perished due to gross negligence on the part of the boat operators was erected in Tompkins Square Park: a small, 9 ft. stele made of pink Tennessee marble, featuring a relief picturing two children looking seaward, sculpted by Bruno Louis Zimm. Funds were provided by the Sympathy Society of German Ladies. In 1991, it was restored by the NYC Parks Department with funds from SUNY-Maritime College in Throgs Neck, Bronx. The children are described: “They were earth’s purest, children young and fair.” A larger monument can be found in Lutheran All-Faiths Cemetery in Maspeth, Queens.

In the mid-2000s, it appeared that St. Brigid’s Church, built in 1848 at Avenue B and East 8th and which had deteriorated nearly to the point of no return, would be razed; however, an anonymous donor swooped in with a $20 million donation which is paying for a good part of what basically became a reconstruction job. Its 1858 church bell is on display on Avenue B.

In its early years St. Brigid’s served a community of Irish immigrant East River dock workers. It was designed by prolific Catholic church architect Patrick Keely. Compare St. Brigid’s restoration to what happened to St. Saviour’s Church in Maspeth, which was constructed in 1847 with a design built by famed architect Richard Upjohn. No angel appeared with a cash donation, and after the property was sold, St. Saviour’s was disassembled and awaits a restoration… somewhere, someplace.

Funeral home ad, Vazac Hall, East 7th and Avenue B. ”Vazac Hall” refers to a former Polish catering hall which opened in 1935. Now it’s the Horseshoe Bar, but often called Vazac’s or 7B.

Named both for the Depression-era catering hall it replaced, and the corner on which it sits, the Horseshow Bar has supposedly played host to the filming of movies like The Godfather Part II, Cocktail and Serpico. But its vibe doesn’t really fit with those flicks, as it’s usually filled with an unlikely mix of fat old guys, cool kids, sports fans and workaday rabble rousers. –Ben Westhoff in the second edition of New York City’s Best Dive Bars (Gamble Guides, 2010)

2023: When the building was renovated, the ad disappeared:

https://evgrieve.com/2023/06/decades-spanning-ghost-signage.html?fbclid=IwAR2GZAACdtQFykFWuKbPuzAJNs2ZwgN-23k2EVxM9EsYZ4xP_ClM4SXe-Ow

Original elements such as ornate doorways and stoop rails on East 7th between Avenues B and C. What are those rusted brackets on the windows at #187 East 7th for?

The East 7th Baptist Church, 207 East 7th, is called (by them) the Graffiti church because of the street art the local denizens kept placing on its properties, though none seems in evidence anymore.

Some engaging Deco detail on #209, next door.

Even more deco at #225, the ground floor of which is the Gethsemane Garden Baptist Church.

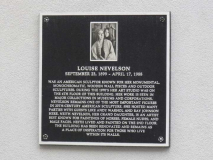

Sculptor Louise Nevelson resided at #222 East 7th Street, which received a bottom to top makeover some years ago. Nevelson’s 1978 installation, Shadows and Flags, can be found at Louise Nevelson Plaza, Maiden Lane and Liberty and William Streets in the Financial District.

Ancient bank, NE corner of Avenue C. Even Jim Naureckas in Songlines doesn’t know what bank this was; he describes it as “building that looks like Cthulhu’s bank has housed artists for decades.”

Cthulhu, the gelatinous, octopus-headed dragon of H.P. Lovecraft’s fevered fiction; the Ghostly Gentleman was always peppering his stories with muti-tentacled, multi-eyed Things that were always being summoned by one incantation or other. But he also was quite the philosopher…

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age. (Lovecraft, in The Call of Cthulhu]

Some information about the bank has surfaced: it used to be the Public National Bank

I found a few NY Times articles on the Public National Bank: In 1920, the bank’s president was Edward S. Rothschild — he made the news when he received a record offer of $1750 a year to lease a building the bank owned at 537 5th Avenue between 44th and 45th. In February 1921 the bank was doing quite well and an embarking on expanding their location at Graham and Siegel in Williamsburg, to a newer bigger lot that they purchased just a block away on Graham. They also had a branch on Pitkin Avenue in Brooklyn, and Delancey at Ludlow in Manhattan. In July of 1921, a teller in their 23rd St. and Broadway branch in Manhattan Ave, succeeded in committing suicide in the bank’s basement by shooting himself in the head. The bank’s 7th and C branch was bought from the J.J. McComb Company in September 1922. A 1990 obit for a former VP and President of the bank, Benjamin Schoenfein, stated that the Public National Bank was acquired by the Bankers Trust Company (now Deutsche Bank) in 1955. I couldn’t find any articles about the E. Village branch closing, but perhaps it happened after Banker’s Trust took over (I’m just speculating). [Forgotten Fan Diane Ingino]

Information about who Sam and Sadie Koenig were, or are, is impossible to glean from my cursory internet searches, but their name is on one of the East Village’s small community gardens on East 7th between Avenues C and D. Whatever building was razed to leave the empty space was quite narrow.

At #242 East 7th,the former Beth Hamedrash Hagadol Anshe Synagogue (“Great House of Study of the People of Hungary”) was designed by the New York architectural firm of Gross & Kleinberger in 1908 and remained in use through 1975. It was converted to condominiums in 1985 and was given NYC Landmarks status in 2008. Presumably, it will have a better fate than another landmarked Hungarian synagogue on Norfolk Street on the Lower East Side, which was abandoned for many years and succumbed to fire in 2017.

Directly across the street is the Iglesia Cristiana Misionera, or Latino Evangelical congregation, here at #247 East 7th since 1954. The building was renovated between 1986 and 1992, perhaps stripping it of some detail.

Esthetics of 1900 and 2018, side by side in your Lower East Side. Actually I don’t mind the building on the right if it were surrounded by similar buildings, but many find the juxtaposition to be jarring.

Jacob Riis Houses, east side of Avenue D from East 6th to East 13th Streets. The Houses were completed in 1949 by the firm of Walker and Gillette.

Jacob August Riis (May 3, 1849 – May 26, 1914) was a Danish American social reformer, “muckraking” journalist and social documentary photographer. He is known for using his photographic and journalistic talents to help the impoverished in New York City; those New Yorkers were the subject of most of his prolific writings and photography. He endorsed the implementation of “model tenements” in New York with the help of humanitarian Lawrence Veiller. Additionally, as one of the most famous proponents of the newly practicable casual photography, he is considered one of the fathers of photography due to his very early adoption of flash photography. While living in New York, Riis experienced poverty and became a police reporter writing about the quality of life in the slums. He attempted to alleviate the bad living conditions of poor people by exposing their living conditions to the middle and upper classes. wikipedia

Riis was a resident of Richmond Hill, Queens, and his daughter was married at the neighborhood’s Church of the Resurrection. His friend Theodore Roosevelt, then Vice President, attended the wedding in 1900.

East 6th Street walkers are carried across the Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive by a pedestrian walkway. I always have a keen eye for them since sometimes they preserve older makes and this one has a couple of ITT/American Electric Model 13s, once a dominant make on NYC streets but now almost entirely supplanted.

I got some photos of East River Park, but Sergey beat me to the post, so I’ll kick it in the head for this one.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

3/18/18

9 comments

You missed the Serbian influence of Kafana on Ave C between 7th and 8th.. 🙂

I distinctly remember the Middle Collegiate Church on East 7th Street having a rather wide staircase leading the arched entrance on the second floor. Looks like they removed the stairs and brought the entrance down to street level. They did a nice job, as it looks like the stone front has been there forever, but I’m talking maybe the mid-1990s/early 2000s.

Is there are reason Staten Island is all lowercase in the paragraph on Tompkins Square? The old Islander in me gets her undies in a knot when I see stuff like that LOL.

Nice job, Kevin, as always!

Did you mean Tim Buckley? I find it hard to believe that W.F. Buckley, noted conservative columnist and would-be aristocrat, would ever be part of that scene.

Nope, Bill

My mother’s grandpa was the super of a tenement at 305 E 7th, which I’m guessing is now somewhere within the Riis Houses. He died in 1941, I still have the old man’s cane.

I assume you meant that St Brigid’s is at East 8th & Ave B. (Besides E 8th at Ave A would still be St Mark’s Pl)

The Koenig Garden on East 7th is at #239. The wonderful book “The Archaeology of Home” by Katharine Greider (2011) is a memoir & history of the house that was there & the entire block. She & her family had lived in the building in 1990s, only to discover it was soon to collapse.

A light bulb went off in my head when I read about the former Public Bank building at Avenue C & E. 7th Street. The description mentioned that in Public Bank’s expansion, a branch was opened at Graham Avenue & Siegel Street, in East Williamsburgh , Brooklyn. In my August 10, 2014 FNY entry, I mentioned that the location LOOKED like it was a bank, but I didn’t know which one. Thanks to FNY fan, Diane Ingino, now we know. I’ve always said that FNY fans know stuff.

You’re welcome!

I was very pleased to see this virtual walking tour! I believe that my grandmother lived in the building next to the Graffiti Church (not the deco one). Her family came to the US from Austria in 1894 when she was 1 year old. Her father had his tailor shop at 168 Ave. A. Her family was part of the St. Mark’s Lutheran Church community. Her mother died within a couple of years after arriving, and the German community connected her father with the Protestant Half-Orphan Asylum on 110 Manhattan Ave., where she lived (very happily) until she was 11 and her father remarried. A double connection wth your article — She was all set to go on the ill-fated picnic excursion on the General Slocum, but was rude to her step-mother that morning. The punishment was to not go on the outing with her Sunday School friends. Years later, my mother told that story to a friend who told her that her grandmother spilled her breakfast down her only good dress and could not go on the excursion.