I was feeling pretty good in November 2011. After an arduous process, Forgotten NY had been moved over to a WordPress platform, though the initial phase was botched by the company I was using and I had to re-do a few hundred pages. I had just been hired for a new job at a company called Medallion Retail, which conceived of ad campaigns but also did signage for Barnes & Noble. And, I was just beginning the process for what became my Forgotten Queens book, scanning almost 1000 photos from which the cream would be culled for the project; the book came out in early 2013. Well, as with most things associated with me it turned into a pile of ‘meh’ as the Medallion job fell through after 3 months; I could not master their ‘voice’ in writing blurbs for author in-store appearances, and we had to traffic our own work instead of relying on a separate department–I wasn’t good at it. Given time, things would have worked out, but they didn’t want to pay health insurance after 3 months. I have had to “rely” on part-time and temporary work ever since as the landscape for copy editing and proofreading has changed.

But this one week in November 2011 I was on top. I appeared on a panel with fellow urban chroniclers at Union Docs, a venue for documentary artists to promote their work, on Union Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. On the stage with me were Nathan Kensinger, now of Curbed, and Nick Carr, then of Scouting NY but now doing Scouting LA. Unfortch, I forget now who the others were. Union Docs has a small room and the house was packed. I’m at my best when doing PowerPoint shows since I can rattle off extemporaneously at length about most every NYC scene on the screen.

This is my second straight Mixed Bag post. I still wander at length from neighborhood to neighborhood, but at length I’ve been wearying of the 100+ photo posts (and I suspect, so have you) that I’ve been doing on Sundays and am looking to do shorter, punchier posts. It might mean I’ll have time to do more.

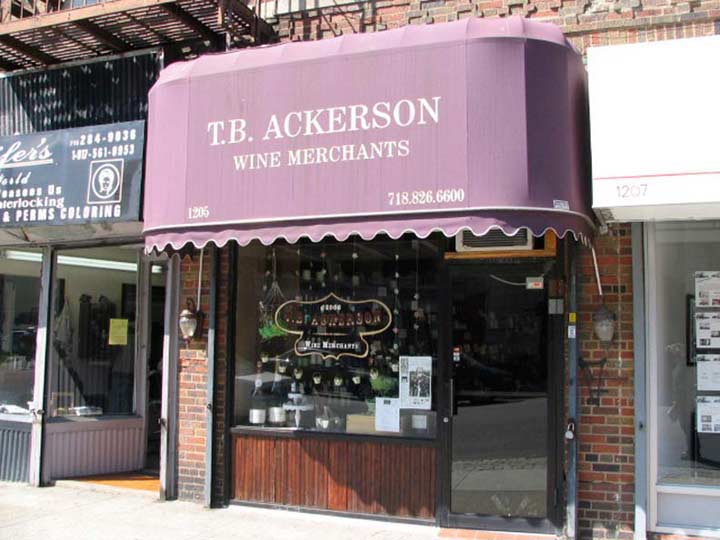

I had found this liquor store on Cortelyou Road in Flatbush (I know the neighborhoods have a myriad of subdivisions; I just call the area Flatbush in general). Immediately I associated the T.B. Ackerson name with something else. I was right, as T.B. Ackerson was the developer behind much of the area, including Fiske Terrace:

In 1905, T. B. Ackerson Company purchased a densely wooded tract of land and immediately cleared it, laid out streets and installed underground water, sewer, gas and electric lines. Eighteen months later, the former Fiske estate had been transformed by some 150 custom-built, detached, three-story suburban houses with heavy oak ornamental mantels, staircases, beamed ceilings and built-in bookcases, ornately bordered parquet floors and elaborate cabinetry. A landscaped median and hundreds of street trees planted at the time of development continue to contribute to the idyllic feeling of the neighborhood. Historic Districts Council

In fact the old T.B. Ackerson real estate office still stands. It is the current stationhouse on the Manhattan-bound side of the Brighton Line Avenue H station, serving the Q train.

I’m always finding yet another red-bricked street in NYC, but they’re always in danger as the NYC Department of Transportation likes to stamp out anomalies. This is Bennett Court on 72nd Street between 3rd and 4th Avenues, in my home neighborhood of Bay Ridge. I’ve found more in Queens and the Bronx, as well as a couple of yellow-bricked roads!

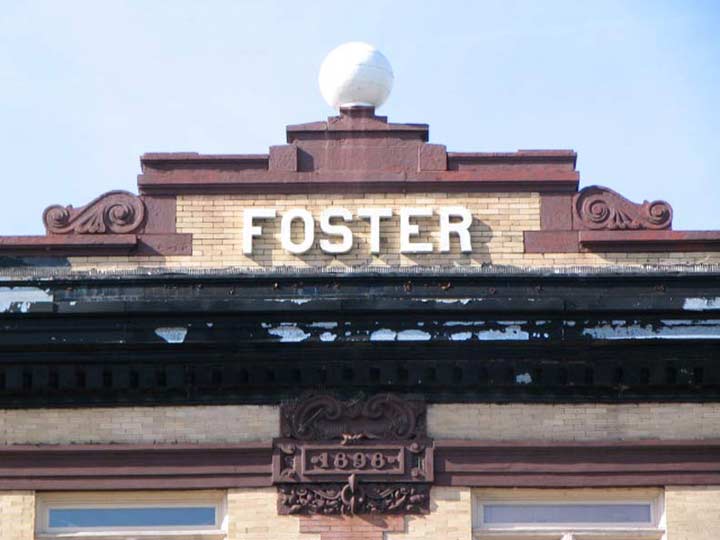

When I visited Portland, Maine a few years ago I found the downtown area dominated by large brick buildings that had commercial businesses on the ground floors and apartment on the 2nd, 3rd and 4th. Also, the buildings were all named “____ Block.” There aren’t very many of those in NYC, that have obvious names anyway, but here’s one on Court and Wyckoff Streets in Cobble Hill. It was probably named for the developer. Note the date of construction on the string course. I wish architects would include those again.

Are trolleys truly extinct? According to the City of New York, they are. But for a brief shining moment in Brooklyn, they weren’t.

There was a Jurassic Park-like experiment that went on in remote Red Hook, Brooklyn, where a Flatbush resident named Bob Diamond dreamt of returning trolley cars to their rightful place on the streets of Brooklyn, where they ran for the greater part of the 20th Century.

Diamond has acquired some trolley DNA in the form an 1897 model from F. Schuckert & Co., built in Nürnberg, Germany, and used in the Oslo, Norway trolley system for many years (and even served as the king’s private car for a time, three 1951 PCC cars that ran on Boston’s Green Line for decades, a switching locomotive, and twelve trolley cars from Ohio. He intended they rid the waterfront streets of auto traffic the way the dinos got rid of hapless villains and extras in the movie.

In 2003, the City pulled the plug on Diamond’s dream. The Department of Transportation insisted that Bob acquire independent funding for the project, and he was unable to do so.

Diamond set in motion a process that he hoped would someday bring trolley service from Red Hook to Brooklyn Heights. He acquired space in the venerable Beard Street Warehouse where he formed the Brooklyn Historic Trolley Association and worked night and day on revitalizing the ancient cars; he had hoped to open the space for a trolley museum, construct trackage from Red Hook along Columbia and Furman Streets to the new waterfront park being constructed there, and perhaps even return the Atlantic Avenue tunnel to revenue service.

For a couple of years, things had progressed steadily, as Diamond constructed trackage in a loop along the waterfront running west from the warehouse, and then along Conover, Reed and Van Brunt Streets. The PCC cars and the magnificent brown and gold Schuckert clanged along the waterfront as tourists marveled.

Diamond had disputes with former volunteers on his team, was evicted from the warehouse after occupying the space rent-free for almost 10 years, and the city grew tired of waiting for Bob to raise funds. At length, the City dropped support for the project, and finally, the Department of Transportation came in and ripped up the tracks and paved the streets in early 2004. By 2014, most of Diamond’s cars were gone, but one, the Green Line car, remains behind the warehouse, which has now become a Fairway Supermarket.

While bicycling all over Queens after moving to Flushing in 1993, I noticed where all the remaining “Olive” stoplights were — there were still a few in far-flung neighborhoods, including a working model at 110th Street and 69th Road in Forest Hills. The DOT removed these remaining working Olives in subsequent years, except for the ones in Central Park — and they’re getting around to those now. This number stayed in service until late 2008, though the city left the old shaft in place.

When the Carroll Street Bridge is mentioned, most people who have heard of it think of the 1889 retractile bridge that crosses Gowanus Canal. However there is a newer Carroll Street bridge several miles to the east, on the other side of Prospect Park, a pedestrian-only bridge between Classon and Franklin Avenues that spans the open cut of the Franklin Shuttle connecting the Fulton Street IND with the Brighton Line. It’s a relic of a long-ago steam railroad, the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island RR. The pedestrian bridge is relatively new, dating to the early 1990s.

The Pink House of Park Slope at 233 Garfield Place between Polhemus and Fiske Places was a dark pink, close to magenta, and it was meticulously kept that way for many years by an elderly owner despite objections by some neighbors, who felt the color is out of character on the brownstone block.

Brown-stone? Not exactly [Brownstoner]

Pretty in Pink [New York Times]

The house is no longer pink, as it was sold by its elderly owner in October 2012 for $2 million. [Brownstoner]

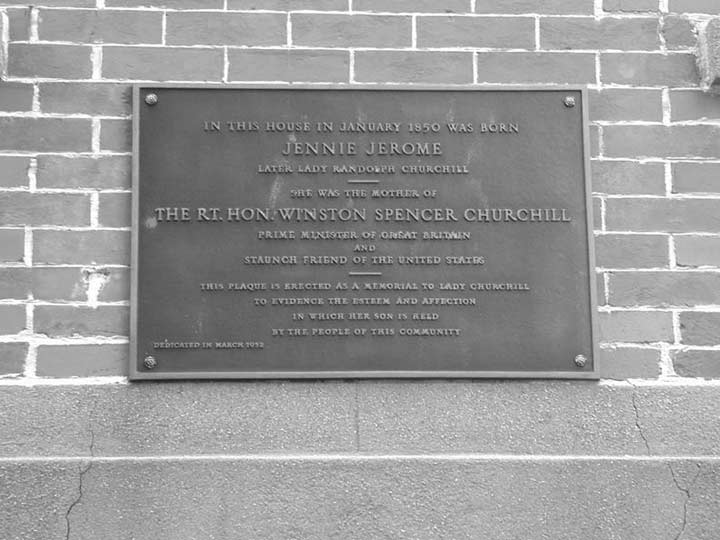

“It ain’t necessarily so”, sings Sportin’ Life in George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, and nowhere is that more apparent than in Cobble Hill, where two houses claim to have been the birthplace of Jennie Jerome, the mother of British statesman Winston Churchill. Her actual birthplace, 197 Amity Street, is unmarked, though its residents report that a plaque is planned, while a house at 426 Henry Street, south of Kane, also claiming to be her home, is the one with the plaque! 426 Henry does have a Jerome family connection: her uncle lived there and her parents, Leonard and Clara, also lived there before the woman who would be known as Lady Randolph Churchill was born in 1854.

Major Markets was a decades-old butcher shop on Surf Avenue in Coney Island that finally went out of business in the late 2000s.

Long after they were removed elsewhere, these 1930s-era octagonal SUBWAY globes stood guard at Court and Montague Streets in Brooklyn Heights until the MTA finally removed them around 2014.

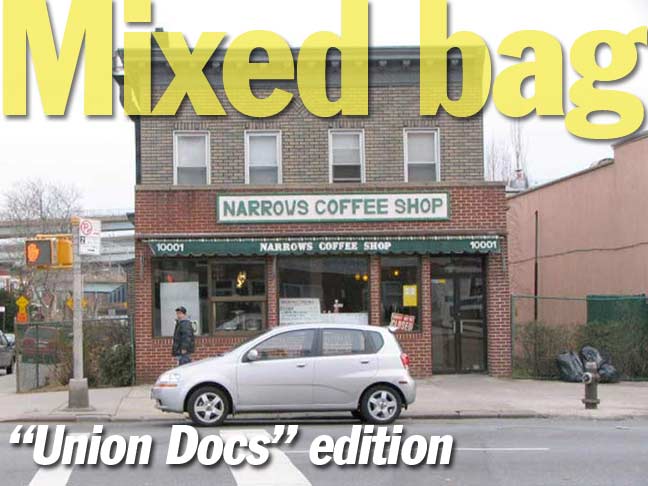

The Narrows Coffee Shop is a true survivor at the heel of Bay Ridge, 4th Avenue and 100th Street, even as new high rise apartment houses are built around it. It’s been here a few decades at least, but when I was a boy, my parents and I ate at the Tiffany Diner on 99th, which succumbed by 2000. Not many 10001 addresses in NYC!

This building at Avenue H and East 12th Street in Midwood was, in a previous life, a SRO called The Hotel Oak. In the 1980s it even had a long-burned out neon sign with the name on it. When I worked at Photo-Lettering in the 1980s, one of my teammates, Joe Orenstein, lived here. He was a man of mercurial temperament. He’d be mentoring me one moment and threatening to kill me the next. He had diabetes and ultimately had some amputations; he passed away several years ago. As far as I know the former Oak still houses transients. It was in extremely bad shape until a 2014 renovation.

Here’s a look at the Oak shortly after its opening in 1908.

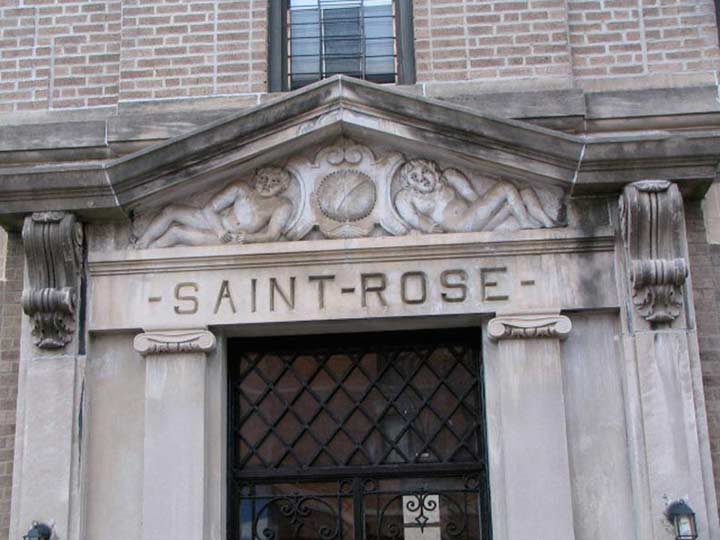

You never know what you’ll find on over-the-door pediments such as the two reclining cherubs on the Saint-Rose, 74th Street just off 6th Avenue in Bay Ridge.

Until Google Maps and my current favorite, Open Street Map (you have to register to see it) the Seeley Street Bridge, a very old concrete span taking Seeley over a valley on Prospect Avenue, is completely undepicted on paper street maps. It still looks like the two streets intersect on paper.

Official MTA redundancy in the 34th Street/Herald Square complex, where the BMT N/R/W transfers to the IND B/D/F. There was a perfectly good tiled sign installed in the 1930s, but it doesn’t have the officially designated Unimark colors. The on;y reason the MTA allows the older sign to be visible is that the newer sign is oblong.

A magnificent artifact of somehow proud architectural disintegration, the Beard Street Red Hook’s Revere Sugar Refinery’s tangled maze of rusted ruins including conveyor belts, bridges and a refining sphere stretched out toward Erie Basin, where they met the sunken St John lightship. The huge domed granary could be seen from all over the immediate neighborhood. The Revere Sugar Corporation operated three refineries, in Charlestown, MA, Chicago and here in Red Hook; the company took its name from Massachusetts patriot Paul Revere. The company, once owned by Antinio Floriendo, known as the “Banana King of the Philippines”, declared bankruptcy in 1985. The refinery was removed around 2010, and the sunken lightship was also.

On a tour in May 2003, Forgotten Fan Mike Olshan introduced us to Sunny Balzano, whose family’s bar on Conover between Beard and Reed Streets has been a Red Hook waterfront institution for three generations, and Sunny treated us all to a brew as we bellied up to a bar that faced several pieces of his own artwork. His family has owned the business for decades, with his uncle John keeping the bar open every day until 6PM, serving sandwiches and Italian food to longshoremen and dock workers.

Gradually, the Red Hook docks became silent as the shipping industry moved across the harbor to New Jersey, depriving the old place of many of its old customers, but Sunny and John discovered that a new clientele of artists and musicians from nearby Williamsburg was coming to the bar. After John passed away in 1994, Sunny ran it as a nonprofit club featuring musicians and local performers, opening Friday nights only, and after acquiring a new liquor license and renovating the bar, Sunny was able to open a couple other nights a week as well. The bar is now a neighborhood gathering place for its new breed of customers, many of whom don’t know it’s a family institution.

Though Sunny passed away in 2016, his wife Tone has been able to keep the lights on, and Sunny’s battered Willys pickup truck is always parked nearby.

The originalBeaux Arts Thomson Meter Building at Bridge and York Streets in DUMBO was constructed in 1908 by Louis Jallade and was one of Brooklyn’s first buildings to utilize concrete. Thomson Meter wasn’t in the building for long, as it outgrew the building and moved a block to Washington Street in 1927. In 2004 the original building was declared a NYC landmark, and its terra cotta work will be preserved.

The LIRR had a surface operation along Atlantic Avenue until 1940, when trains were finally placed in a tunnel in some places and elevated tracks in others. A tunnel between Court Street and the waterfront was used for only a few years, beginning in 1844, before the western terminal of the Long Island Rail Road was placed at Flatbush Avenue; the last train ran there in 1859 and the tunnel was sealed in 1861. It is 17 feet high, 21 feet wide, and about 2000 feet long.

Bob Diamond formed the Brooklyn Historic Railway Association in 1982 to restore the tunnel. The Association won the tunnel a place in the National Register of Historic Places, and Diamond periodically hosted tours of the tunnel for the public before the FDNY ceased them for safety reasons. Diamond has an ongoing dream to run trolley service in the tunnel and along the Brooklyn waterfront, and maintains there is a locomotive somewhere in the tunnel.

Samuel Underberg, a food supplies company, had offices in this building that stood on Atlantic Avenue between Flatbush and 5th Avenues for many decades, and the company made sure you knew it with large painted identification on all sids of the building. Over a decade ago, Underberg moved east on Atlantic Avenue to Utica Avenue, and the building, and its signs, lay empty. In early 2006, it was razed by Forest City Ratner in anticipation of using the land for its Atlantic Yards project. “Underberg” was used by Jonathan Lethem for the first section of his novel “The Fortress of Solitude.” This space is now occupied by the vast Barclays Center sports and performance space.

Atlantic Avenue at the junction of Fort Greene and Prospect Heights, long before it became a retail and entertainment center, was home to slaughterhouses and meat wholesalers. When I went to high school in the area in the 1970s, I frequently walked past hooks on which sides of beef were swinging. This has all vanished, much as NYC’s “other” meatpacking district in the West Village has, mostly. The Underberg Building was its last trace.

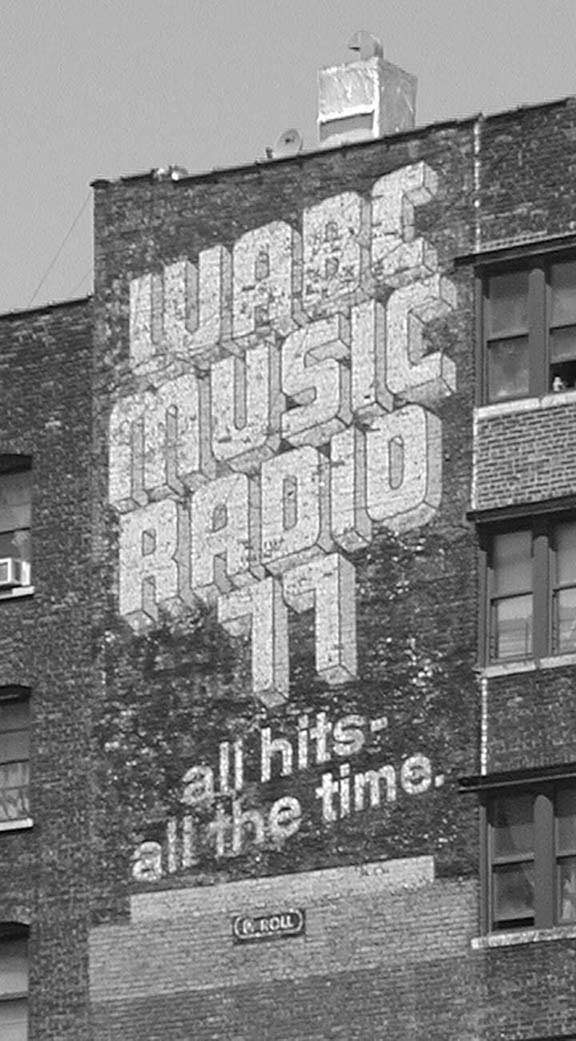

WABC 77 played pop music between 1960 and 1982, with its unforgettable complement of disc jockeys that included “Cousin” Bruce Morrow and Dan Ingram. This ad was likely painted on the side of the corner building at St. Nicholas avenue and West 145th Street in the 1970s. It held up remarkably well and is still there — but now it’s obscured by a high rise.

On the south side of Webster Place near Prospect Avenue in Windsor Terrace, there seems to be a little piece of San Francisco or Seattle here, with a grouping of beautifully painted, porched Queen Anne-style houses.

If you own or know the story behind one of these beautiful buildings, let me know. All are meticulously maintained, at least on the outside. Shouldn’t the Landmarks Preservation Commission take a look here?

Sadly this was the last of Brooklyn’s “humpbacked” street signs, lasting on Willoughby Street at the University Towers Houses east of Flatbush Avenue Extension all the way to 2016, when the Department of Transportation finally discovered and removed it. The brackets once held a One-Way sign, while the cross street, the vanished Hudson Avenue, can be seen in the “hump.”

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

8/26/18

1 comment

Hello fantastic website! Does running a blog like this require a large amount of work?

I have no knowledge of coding but I had been hoping to start my own blog soon. Anyway,

if you have any recommendations or techniques for new blog

owners please share. I know this is off subject but

I simply had to ask. Thanks!