Well-worn territory for sure, but from November to February I did a fair bit of walking around in Astoria, especially in its northern stretch. This week, I wanted to do a relatively quick and easy Sunday-Monday page as last week’s Presidential extravaganza was pretty exhausting to write. I settled on this walk from Queensboro Plaza to the 46th Street subway station on Broadway.

The Steinway family, master piano builders, transit magnates, and resort developers, put a personal stamp on the neighborhoods in which they resided that is visible even today. Henry Steinweg, a German piano manufacturer, immigrated to New York City from Seesen, Germany, in 1853. His sons Henry Jr. and Theodore set about making the finest pianos ever made, renowned the world over.

Henry Jr.’s and Theodore’s younger brother, William, continued the family tradition (advertising their instruments as “the standard piano of the world”) and moved the operations of Steinway Pianos to Astoria, Queens. Between 1870 and 1873, Steinway purchased 400 acres of land in northern Astoria and not only built the spacious Steinway piano factory, which still cuts an imposing figure, but a small town with a library, a church, a kindergarten, housing for factory workers, and a public trolley line. From 1877 and 1879, Steinway constructed a group of handsome row houses on Winthrop Avenue (today’s 20th Avenue) and on Albert and Theodore (41st and 42nd) Streets. Even the street names bore witness to the Steinway family, since Albert and Theodore were sons of Henry Steinway. These homes were rented by the Steinways to their workers. William Steinway’s mansion, on 41st Street, still stands on a high hill that has never been leveled, unlike the surrounding area. 41st still looks like a country lane in spots.

My walk took me on Steinway Street for part of the way. Unlike surrounding streets that have had successive names or numbers, Steinway Street, which takes the place of 39th Street on the present map, has always been called Steinway Avenue or Street. It is one of the area’s busiest shopping/restaurant strips along with Broadway and 30th Avenue, and runs from Northern Boulevard to an ignominious finish, a sewage treatment plant along the East River.

Queensboro Plaza is where the #7 and N trains meet and then diverge toward Ditmars Boulevard and Main Street. Until 1942 the Second Avenue El coming over on the Queensboro Bridge had joined the party. Its superstructure had covered the northern part of Queens Plaza North for a decade or so after the last el train had stopped running.

Formerly a sleepy area featuring fast food joins, hookers and a couple of office buildings (one of which was the Brewster Building that produced auto and airplane parts) Queens Plaza has seen tall glassy towers spring up along its southern side like those crystal entities in the old 1950s film Monolith Monsters. Along Queens Plaza the towers contain offices but south of there, they feature expensive residential spaces.

This relatively new building on the NW corner of Queens Plaza North and Crescent Street bears the logo of the Ecuadorian Consulate. There are thousands of immigrants from South America in Queens, especially further east along the #7 train on Roosevelt Avenue, so it makes sense that the consulate is located in Queens.

Crescent Grill, Crescent Street and 39th Avenue. Someone thought making a restaurant look like a library would attract patrons. For all I know, they’re right. I’ve criticized restaurant appearances before in FNY, and heard from the owners, so I’ll just say everything’s a matter of… taste.

An impulse compelled me to get a shot of this 3-story walkup apartment on Crescent Street. Perhaps the realization that it still stands stolidly amidst all the changes that have come to this part of town.

I can’t resist this ancient Queens track between 37th and 39th Avenues and 29th and 30th Streets. The Department of Transportation doesn’t mark it but it’s known on Open Street Map and Google Maps as Ridge Road or Old Ridge Road. No one who uses it as a driveway or for parking knows it’s an original road in western Queens.

If you check this 1852 Dripps map of the area, you can see Ridge Road as a diagonal just below the words “Dutch Kills.” You also see “harris,” “Van Alst” and “Payntar.” These were all early property owners in western Queens, when this was still a part of Newtown. Streets were later named for them that were even later numbered as part of Queens’ street numbering scheme. Note the tributary of Newtown Creek that ran all the way to this point. It has since been diverted underground.

The reason this small piece of Ridge Road survived is because it was used for a trolley route early in the 20th Century. In fact, I once found an exposed rail here that seems to have since disappeared. FNY has the full Old Ridge Road story here.

I thought I had found a Ridge Road address. However this building also fronts on 38th Avenue, and its address (29-05) is on that street.

Facing off across 38th Avenue at 32nd Street are two separate visions of residential housing, from 2015 and from 1895.

I can tell that the buildings along this stretch of 38th Avenue are pretty old, despite their age-concealing aluminum siding. The tell is the bluestone sidewalks, which were installed in the early 20th Century; the city stopped using this sort of sidewalk paving in the 1920s, preferring poured concrete. These days, pavements also have metal framework bases.

The Addition, a 2016 residential building at 33-01 38th Avenue, is so-called because it was built atop a previously existing, low rise commercial building. it employs the current fashion of using flat panels snapped into place on the framework surrounding picture windows.

Am I a bad guy for mentioning that I don’t mind this sort of design all that much? I’ve seen much worse.

At 34th Street and 38th Avenue you encounter the former Pierce Arrow auto distributorship, a mighty brick building with terra cotta elements.

Pierce-Arrow, based in Buffalo from 1903 to 1938, evolved from a luxury birdcage manufacturer established in 1865, Heinz, Pierce and Munschauer. Henry N. Pierce bought out his two partners and began building and retailing bicycles and motorcycles in 1896, with the leap to automobiles in 1901. The company’s first success, a two-cylinder auto, named the Arrow, appeared in 1903. The company’s first commercial success, the four-cylinder Great Arrow, arrived in 1904. Though George Pierce sold all his company rights in 1907 and passed away in 1910, the company was known as Pierce-Arrow from 1908 to 1938.

Pierce-Arrow’s 1913 Long Island City factory still stands on 38th Avenue between 34th Street and Northern Boulevard across from, appropriately, a gas station. Longtime readers of FNY know of my admiration for stolid brick architecture, and the factory imparts a sense of permanence, even though its parent company existed for only thirty years. The building once had a lengthy, arrow-shaped neon sign, emblazoned with the word “Pierce.”

Here’s the full FNY story, with more photos and details.

This huge building stretching along 37-18 Northern Boulevard in Long Island City is home to Standard Motor Products. SMP was founded in 1919 by Elias Fife and Ralph Van Allen, producing electric parts for the auto industry, then poised to become a major player in the 20th Century. The firm moved to Queens as early as 1921 and bought its present-day behemoth in 1936. SMP has sold the building since, but remains a tenant.

I filled in here for just two weeks after my first layoff from Publishers Clearing House in November 1999, but I’m happy to have been involved with such a longstanding institution. Many of the interiors had seemingly been left unchanged in decades, and I especially liked the bathrooms. Why? I could look out the windows onto the Sunnyside RR yards, which are just behind the building. The city and real estate developers consider the yards a waste of real estate, and are looking to deck them over and build condo towers on them.

For the last decade, 37-18 Northern Boulevard has had an added function: commercial farming at the Brooklyn Grange.

Standard Lane, possibly the shortest dead-end in Queens, fronts on Northern Boulevard at 37th Street. It’s fairly busy, though, as it services the interior garages of both industrial buildings on either side. It was named decades ago for Standard Motor Products.

A doorway on 38th Street between 34th and 35th Avenue. I noticed the sign above the door, “G & M Machine Products.” This company seems to be now nonexistent, as there are no internet listings for it.

Many Astoria blocks are an interesting mix of industrial and residential. Here’s a quartet of handsome brick residences across the street a bit north of the old motor products place. It hasn’t been resided and most of their details have been preserved.

This building at 32-14 Steinway Street jut south of Broadway looks pretty modern, with its stucco front painted a snazzy gold, doesn’t it? It’s got a secret. Check out that aged dormer window at the top. A few months ago, FNY had the scoop.

A pair of identical 3-story commercial buildings face off across Steinway Street at Broadway. These, and the buildings shown below, date from the late 1910s-early 1920s.

In the 19th and early 20th Century, this commercial building at the SE corner of Steinway Street and Broadway was the site of one of Queens “Scheutzen” Parks, scheutzen being German for “shooting.” Yes, there were once combined beer gardens and target shooting ranges. Image: Greater Astoria Historical Society.

Egypt Royal Cuisine, 30-91 Steinway, has an extravagant exterior. Steinway Street, especially near the Grand Central Parkway north of here, boasts many Middle Eastern restaurants and businesses. It’s a combined restaurant and hookah lounge with the smoking confined to the 3rd floor.

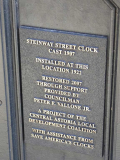

The Steinway Street Clock, in front of 30-78 Steinway between 30th and 31st Avenues, is one of a number of large, stolid street clocks designed by George Post. Except for a few years in the 2000s when it was taken away for repairs, it has stood here since 1922 — although it was first cast in 1907. There are 7 landmarked George Post clocks in NYC; the other one in Queens is at Jamaica Avenue and Union Hall Street.

The clock stands in front of the former Wagner Jewelers.

The former Astoria Theatre stretches on 30th Avenue, fronting on Steinway Street, rear-ing on 38th. The Astoria opened in November 1920 as a 2750-seat, one-screen, one-auditorium venue that, like most theaters of its time, was also home to musical and vaudeville acts. It survived as a theater until fairly recently, closing on December 26, 2001 as the United Artists Astoria Sixplex. Home to a Duane Reade drugstore and a gym chain now, it’s still quite recognizable as a former theater, with its grand arched entrance and marquee still intact.

Here’s the Astoria in full glory in 1940.

The opposite corner has seemingly always been nailed down by a cigar store; check the 1940 photo linked above, when it was Union Cigars. I like this sign, which has a twin on Steinway Street, using the Futura Condensed font.

A few doors away, at 28-53 Steinway Street, is an example of an apotheosis of a genre: high Art Deco. They style was introduced in Paris in 1925 and spread like wildfire as an architectural style, peaking from 1928-1935. Plenty of colored terra cotta tiling as here can be seen on may of the buildings featuring the style.

Another relic on Steinway Street is a classic Bishop Crook at 28-43. The classic appended humpback signs advertise the name of a former hair salon. The post is shorter than most Bishop Crooks, so the central part of the shaft may have been removed, or this was a short “dwarf” version used beneath elevated trains.

There was some very good news with the post because Google Street View shows that the DOT, or some entity, has installed a new Bell-style LED light fixture.

Do not mourn the hairdresser, by the way. It simply moved across the street.

Straus Paint and Hardware is apparently Steinway Street’s oldest business and has operated here at 28-09 Steinway Street since 1930, by four generations of Strauses. The venerable sign appears to be from the 1940s, 1950s at the youngest.

Continuing the theme of sidewalk signs, here’s another for Fatty’s Cafe at 25th Avenue and 47th Street. It is a neighborhood restaurant serving Latin-American specialties.

Before wrapping it up for the day (I told you this will be short) I’ll show you what some say is evidence of a small hamlet called Middletown or Middleburg, located at today’s Newtown Road and 46th Street. Returning to the 1852 map, I’ve marked roads that evolved into today’s Newtown Road, Broadway and 39th Avenue. Broadway took a short jog to meet Newtown Road, and that jog can be see today, apparently, in the angles and curves the buildings take. That’s because while that bit of road has long vanished, it dictates property lines that are adhered to till today.

On East 42nd Street, the east end of the Chysler Building plot is angled. That’s because it had to avoid the Eastern Post Road, which vanished in the mid to late 1800s, but still leaves its ghost in property division lines!

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

3/3/19

4 comments

Poured concrete became the material of choice for sidewalks (and building foundations) in the 1920’s because that’s when ready-mix trucks were invented. Prior to that the only way to build with concrete was to set up a concrete plant right at the job site, which was impractical for all except the very largest projects.

Kevin, the Loew’s Triboro was at the N/W corner of 28th Ave. & Steinway. It was a magnificent theatre, unfortunately torn down for homes & stores. I don’t remember the Astoria being part of the Loews chain.

And I believe the German park was on the opposite side of Steinway, between Broadway & 34th ave. .

For Queens history look up the books of Vincent Seyfried. He is the premier researcher, also the LIRR.

Crescent Grill, for all of its lack of exterior charm, is one of the area’s best hidden restaurants, rivaling anything in Astoria. Its hours might be a bit odd (no Saturday brunch, only Sunday??), but the food is delicious. My wife and I had our family brunch here the day after our wedding at the Paper Factory a few years ago, and have celebrated anniversary dinners there since. There’s a small gallery in the front too. Credit where credit is due!

Next door to Egypt Royal Cuisine used to be the Mets store, which only last a very short time. Late nineties or early 2000s? You can still see the Mets colors in the facade.