I had last been in New Dorp and the Todt Hill, Staten Island area in January 2018 when I visited the Ernest Flagg Estate, which became St. Charles Seminary, with one of the ex-seminarians who had also attended high school with me, Brian Zuar. This time, I decided to walk from New Dorp back to Clifton and then catch the Staten Island Railway to the ferry, Today, I’ll concentrate exclusively on New Dorp.

From the ForgottenBook: New Dorp is a transliteration of Dutch nieuw dorp, or “new town,” so called because it was settled in 1670, ten years after nearby “oude dorp”, a name remembered in the street name Old Town Road. The town grew up around the junction of Richmond and Amboy Roads, where there were a proliferation of taverns serving stagecoaches and horse-drawn carriages. The Vanderbilt family was prominent in the area and owned several racing and trotting tracks in the area. The family helped found the New Dorp Moravian Church and Cemetery along Richmond and Todt Hill Roads; the Vanderbilt Mausoleum, built for one million dollars and designed by Richard Morris Hunt, can be found at the cemetery’s rear section.

Like many stations along the Statn Island Railway route along the island’s south shore, there’s an impressive-looking brick stationhouse. However there is no interior waiting room and no way to purchase rides; indeed, mid-Islanders can ride free of charge between all stations with the exception of the South Ferry and Tompkinsville stations, which have “turnstiles.” The reasoning is that most Islanders who ride the SIR need to get to the ferry and thence, Manhattan. Before 1997, tickets were purchased with cash from the conductors on the trains; this system was also in place for a few decades on the Dyre Avenue Line between East 180th and Dyre Avenue in the Bronx.

Several stations in mid-Island are relatively new as is the open cut trench the trains run in. The fencing and lampposts are unique in NYC and date back to station renovations that took place in the late 1980s and 1990s. The fence appears unfinished as it looks like the primer paint coat is still there.

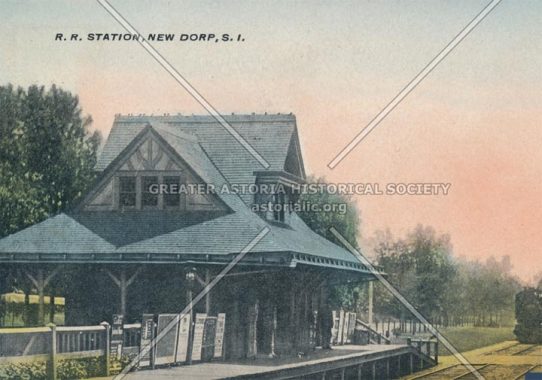

Before 1965 the New Dorp station ran at grade and vehicular traffic was controlled by gate crossings. The Victorian-era station house was removed to Richmondtown Restoration at about this time.

Although they’re aluminum-sided these bay-windowed buildings along the west side of New Dorp Plaza,which runs on both sides of the SIR, have survived relatively unchanged since they way they looked in 1940.

It seems like dancing schools and railroad stations go together, as you usually find the former close to the latter.

Unsurprisingly, the Tottenville-bound entrance is in dire need of repair with holes in its roof, while the Manhattan-bound is in good repair.

Staten Island’s commuter railroad, established by Erasmus Wiman in the 1800s, resembles a NYC subway, with R-44 cars formerly used on subway routes, but it’s governed by railroad rules. Under the aegis of the Metropolitan Transit Authority these days, it was formerly run by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Between Richmond Road and Hylan Boulevard, New Dorp Lane (the prominent east-west strip) is lined with Type B Henry Bacon-designed sidewalk lampposts, usually found in parks.

Although in the past, there have been other sets of numbered streets in Staten Island, the ones in New Dorp are the only ones remaining, and they’re only 1st through 10th. 5th and 6th Streets are missing: they’re on either side of the railroad, and New Dorp Plaza stands in for them. Of course Manhattan, Queens, and large portions of the Bronx and Brooklyn heavily feature numbered streets.

There are a pair of historical plaques at the busy junction of Richmond Road and New Dorp Lane. The larger of the two commemorates New Dorp’s World War I dead…

While the second, installed by the Daughters of the American Revolution, marks the Rose and Crown Tavern, which stood here during the Revolutionary War. New Dorp figured prominently in the Revolution.

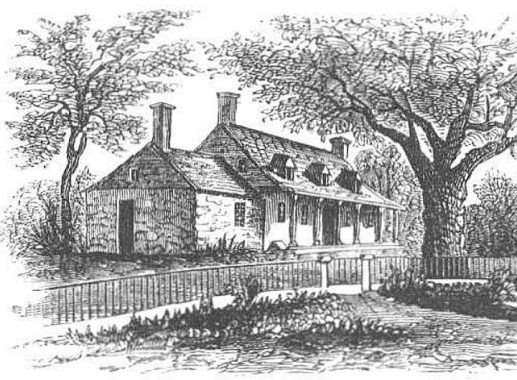

Two taverns, about a block apart, were occupied by British officers including commander-in-chief General William Howe. The Rose and Crown was a one-story building with a central hall and rooms on either side, “guarded” by a large elm tree. The tree was cut down long ago, but has lent its name to the dead end Elmtree Avenue off Hylan Boulevard and the Elmtree Beacon at New Dorp Lane where it meets Raritan Bay. The Rose and Crown stood until about 1865.

Howe actually made his headquarters at the Black Horse a block away at Richmond and Amboy Roads, a building that lasted long enough into the 20th Century to make its way onto historic photographs and postcards. In this photo, Amboy Road is on the left, Richmond Road on the right.

Nearby on Richmond Road between New Dorp Lane and Amboy Road is the Gustav Mayer House, an ornate, suburban “villa,” built in 1857 in the romantic Italianate style, set on a knoll and boasting a cupola that offers views of Raritan Bay and a full-width front veranda. For more than a century, until 1990, it was occupied by family members of Gustav Mayer, a wealthy, German-born businessman who was a major innovator in the cookie industry, as the inventor of the Nabisco Sugar Wafer. Much of its Italianate features have remained intact, but a paint job would help.

Meanwhile back on New Dorp Lane is Our Lady Queen of Peace Church and its satellite school, rectory (priests’ residence) and office buildings. The parish was established in 1922, with its first Masses taking place in the aforementioned Black Horse Tavern. This English Gothic parish church building was constructed in 1928, and seems to have an offbeat selection of liturgical tunes in its chimes rotation; when I passed, it was playing the Irish classic, “Galway Bay.”

No, this is not Saint Unicorn. It’s an apostle (I don’t know which of the twelve) displaying the “tongue of fire” bestowed him by the Holy Spirit, an event now commemorated by Pentecost Sunday in June. The Holy Spirit’s visitation bestowed the zeal and requisite “gift of gab” needed to preach the Gospel. The apostles spread out to far flung outposts in the Old World spreading Christianity; unfortunately, eventually, all were martyred.

Cloister Place, seen here at 3rd Street, runs for a couple of blocks just north of New Dorp Lane. I’d think that its name has something to do with its nearness to the church.

From Staten Island’s Military History Trail: The New Dorp World War II Memorial was erected in September 1947 by the Citizens League of New Dorp. The large granite memorial is dedicated to the residents of New Dorp who served in World War II. The ceremonies that accompanied its unveiling included a parade that featured five marching bands, speeches by prominent local officials, and members from several veterans’ groups. The inscription on the memorial reads: “New Dorp Honors Its Men and Women Who Have Served in the Armed Forces During the Second World War, 1941-1945.”

The Art-Deco themed Lane Theatre, 168 New Dorp Lane near 10th Street, was developed by the Moses brothers, Charles, Elias and Lewis, opened in 1937 and designed by renowned architect John Eberson; the first feature was “100 Men and a Girl” starring teen singing sensation Deanna Durbin. The Lane featured a modest 600 seats in its heyday, later reduced to 550. Until 2001, it had been recast as a nightclub that has now closed, though the distinctive red and blue “Lane” façade is still visible. In the Lane’s last gasp of notoriety, one Marshall Mathers III, a.k.a. Eminem, played here in the spring of 1999. Its Art Moderne foyer and corridors remain intact, now a part of the Crossroads Church.

The handsome Federal style clock towered building at New Dorp Lane and Edison Street was originally built as a branch of Staten Island Savings Bank. SISB was absorbed into what is now Santander in 2007.

For many years I bought comics and graphic novels at Jim Hanley’s Universe on 33rd Street in Manhattan (which is now on 481 3rd Avenue) and I was surprised to find one here on New Dorp Lane. However, this is the original location, founded by Hanley in 1983.

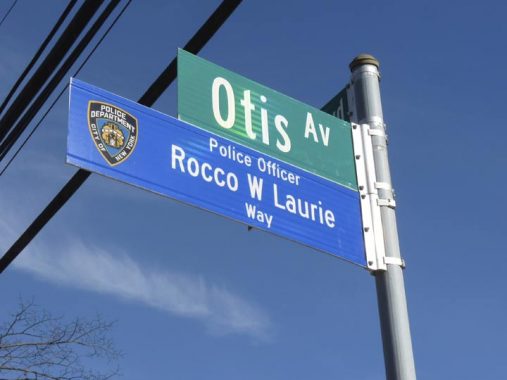

Otis Avenue and Hylan Boulevard. I like the Department of Transportation color sign scheme for honoring fallen NYPD officers and FDNY firemen: blue for NYPD and red for FDNY.

Just northeast of New Dorp is Grant City, named for President Ulysses S. Grant by prominent businessman John Thompson in the 1880s. The London plane tree is by far New York City’s most numerous, but Grant City takes things to another level: each and every street in the enclave, bordered by Richmond Road, Jefferson Avenue, Locust Avenue and Hylan Boulevard is lined by hundreds of London planes, some of them over a century old.

There are also some eclectic mid-20th Century homes to be seen along its streets as well.

I note this Victorian-era house at the corner of Lincoln Avenue and Edison Street every time I’m in the area. Its owner meticulously cares for it even down to placing mini-sculptures, similar to those seen during the holidays at the New York Botanical Gardens Train Show, on the mailboxes.

Between Stobe and Seaver Avenues, most north-south streets are interrupted by New Creek, which runs from Last Chance Pond (see below) to Raritan Bay through marshy Midland Beach. Hylan Boulevard, seem here, Richmond Road, and Olympia Boulevard are the only routes through the region from north to south.

Seaver Avenue runs west through a Little League field to Husson Street and what appears to be an empty lot. However, this is a piece of the Staten Island wetlands that was ignored by all but the most detailed topographical maps; Hagstrom and Geographia assumed it would be drained and developed, and so showed the streets that developers were hoping to build through it. Such lofty plans evaporated, though, and so what is called Last Chance Pond still remains here.

According to the NYC Parks Department: “Efforts to preserve the pond and wilderness area began in earnest in the mid-1960s. Local residents Louis Caravone (currently Chair of Community Board 2) and John P. Mouner of the Beachview Manor Citizens Association enlisted the support of a formidable cadre of politicians and environmental groups to aid their efforts. Together, they helped found the Last Chance Pond and Wilderness Foundation… The endangered property in the area of the current park was ultimately purchased by the New York State Nature and Historical Preserve Trust, a non-profit organization, which then donated the land to the City for park purposes. Finally, in 1999, the area of the current park was assigned to Parks by Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) on December 30, 1999.”

In contrast to the New Dorp and Grant City stations, the SIR’s Dongan Hills station was constructed in the 1930s, eliminating a prior grade crossing on an elevated structure. Like all other SIR construction of the 1930s it eschewed an ornate style in favor of avery simple, basic unadorned construction. In the late 1980s/early 1990s, these stations were partially reconstructed with the notable use of glass blocks that graffiti and scratchiti people found irresistible.

In a borough renowned for some of the best pizza in NYC, the unmarked Lee’s Pizza, at Garretson Avenue and Hancock Street opposite the station, stakes its claim.

I continued through Dongan Hills to Clifton, but that will wait for a further segment.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

12/29/19

7 comments

It’s a long hike from the New Dorp station toward the water, but Miller Field is an interesting spot in many respects. Now part of Gateway NRA used mainly for sports activities, it was a military air field for about 50 years starting in World War I. Today there are some remnants of its former use, most notably a couple old hangars just begging for restoration. A concrete parking area in front of the hangars floods easily and attracts ducks and geese. There’s a concrete observation tower on the beach, and a number of older wooden houses once used for military officers but today housing parks service employees. The runways had never been paved, so there are no remaining traces of them.

Miller Field was the crash site of the TWA plane that was involved in the 1960 midair collision and Park Slope crash. It is not known whether the pilot was trying to make an emergency landing or if the airplane was completely out of control and just happened to crash on an airfield.

Staten Island once was home to three airports in addition to Miller Field. Staten Island Airport on the east side of Richmond Avenue was the largest and busiest, housing a number of private aircraft for about 20 years starting in the early 1940’s. It closed in the early 1960’s and today the Staten Island Mall occupies the site with no traces of the airport remaining.

Right across Richmond Avenue was the separate, much smaller Donovan-Hughes Airport, open from about 1930 to 1950 and soon after buried completely under landfill. Finally, the similarly small Richmond County Airport was open for about ten years in the late 1940’s to early 1950’s on the western end of Victory Boulevard near the water. Construction of the West Shore Expressway and a power plant obliterated all traces of it.

That’s Saint Jude, who’s traditionally depicted with the tongue of flame as well as a club, which was the instrument of his martyrdom.

I was born on Staten Island late 1954. My parents and I left the island the day after my second birthday. We constantly went back as my both grandmothers lived in New Dorp.

When visiting, we would go back to the cemeteries. On the hill in Moravian (at the time, one could see the fence in the distance of the Vanderbilt Mausoleum grounds and could barely make out the building itself in the distance) was what was left of a green windmill minus the blades. My father and I had a conversation about that windmill many times as I bemoaned the fact that it was dismantled. He often said that the blades were never on it his entire life, he was born in 1921. Around the mid-1960’s one could go to the site and still see parts of the foundation, caved in. Never have I been able to find a photograph of the windmill nor what was left of it at the time. I contacted the cemetery a few years back and no one there had knowledge nor memory of it.

I was born on Staten Island late 1954. My parents and I left the island the day after my second birthday. We constantly went back as my both grandmothers lived in New Dorp.

When visiting, we would go back to the cemeteries. On the hill in Moravian (at the time, one could see the fence in the distance of the Vanderbilt Mausoleum grounds and could barely make out the building itself in the distance) was what was left of a green windmill minus the blades. My father and I had a conversation about that windmill many times as I bemoaned the fact that it was dismantled. He often said that the blades were never on it his entire life, he was born in 1921. Around the mid-1960’s one could go to the site and still see parts of the foundation, caved in. Never have I been able to find a photograph of the windmill nor what was left of it at the time. I contacted the cemetery a few years back and no one there had knowledge nor memory of it.

The green windmill in the photograph (see link) is the shape of the one that was torn down on the hill of Moravian Cemetery (see aforementioned posting of mine). Similar green color.

https://pixabay.com/photos/zaandam-mills-zaanse-schans-view-592951/

(Original posting disappeared)

I was born on Staten Island late 1954. My parents and I left the island the day after my second birthday. We constantly went back as my both grandmothers lived in New Dorp.

When visiting, we would go back to the cemeteries. On the hill in Moravian (at the time, one could see the fence in the distance of the Vanderbilt Mausoleum grounds and could barely make out the building itself in the distance) was what was left of a green windmill minus the blades. My father and I had a conversation about that windmill many times as I bemoaned the fact that it was dismantled. He often said that the blades were never on it his entire life, he was born in 1921. Around the mid-1960’s one could go to the site and still see parts of the foundation, caved in. Never have I been able to find a photograph of the windmill nor what was left of it at the time. I contacted the cemetery a few years back and no one there had knowledge nor memory of it.

Thank you for your write-ups of Staten Island! It is so often the forgotten borough. If you have not already, it would be great to include a part on Staten Island

Technical High School building (10th Street) in New Dorp. The high school used to be McKee Career & Technical High School but the building was ceded to

Staten Island Tech sometime in the 1980s/90s. Back in the past, the grounds of the high school was informally opened to the neighborhood and kids and adults

often walked the track for exercise at dusk after work or played tennis on the concrete courts. In the early 2000s, Staten Island Tech cut off access to the grounds

and it remains a no go area for the neighborhood residents. It is a pity because it takes up so much neighborhood space and many of the kids in the surrounding

area do not go to Tech. I guess it is a sign of the times that public facilities are not true public facilities anymore!