In 2019, I made three separate pilgrimages and Walks of Penance in Fort Wadsworth, Rosebank and Clifton areas on the east shore of Staten Island. The first was on January 1 and the other two were in late spring, May and June. On the third I was accompanied by over a dozen people since that was an actual Forgotten NY tour I was doing; the first two trips were “scouting missions.” I’ve visited Clifton and Rosebank on numerous occasions, and even took a room in a bed & breakfast on Hylan Boulevard and Edgewater Street for a week in February 2005 to easily get the photos I would need for the Staten Island listings in Forgotten New York the Book, published in September 2006. Of course, every time I visit, I find something new.

My January 1 visit was during a period in which the government had run out of money and basically, everything was shut down, including the Fort Wadsworth visitor’s office. I wanted to ask the park rangers if group tours not conducted by park personnel were permitted. When I visited again in May the rangers assured me they were, and one even accompanied us: I’ll get to that in just a bit.

My walks took me to different locales while in the end, depositing me on Bay Street where I could get a bus back to the ferry. Thus, I’ll be posting images on several different pages. Here, I’ll concentrate on the May walk, which was the longest, and I’ll make it a multiparter to prevent wearing me, the writer and you, the reader, out. By the way, after the tour in June 2019, the postgame show was held at J’s on the Bay, 1189 Bay Street off Hylan: we always seem to end up at diners and here, the food is good and the decor consists of chrome, red and white, which is just fine with me. Of course, dining in isn’t an option during the Covid Crisis.

I miss doing the physical tours and am working on using Zoom and Powerpoint to do virtual ones. If I master it, it’ll be a year-round option.

GOOGLE MAP: FORT WADSWORTH & ROSEBANK

To get to Fort Wadsworth I took the S53 bus from Bay Ridge across the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge and de-bussed at the first stop, Lily Pond Avenue and Major Avenue. Here, there is a private road leading into TBTA offices as well as a marble monument and brass plaque installed when the bridge opened in November 1964. At the time it was the longest suspension bridge in the world and is still in the top 15.

This house, at lily Pond and McClean Avenues, is one of only two buildings in New York City that were designed by the famed architect Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886). After the architect married Julia Gorham Hayden the couple settled in Staten Island at the encouragement of HHR’s friend, Frederick Law Olmsted, co-creator of Central and Prospect Parks, who was also a Staten Island resident at the time at the south shore in Eltingville. Richardson designed and built his family’s home here in 1868 and it was finished the following year. In 1874, however, the Richardsons moved to Brookline, Massachusetts so he could supervise what many architectural critics say is his masterwork, Trinity Church in Copley Square in Boston. The house was landmarked in 2004 after some up-and-down years. [Landmarks report by nyc.gov]

It was time to enter Fort Wadsworth. Though it’s decommissioned and is no longer a U.S. Army base, and is now under the auspices of the National Parks Service and the Department of the Interior, I always expect to be stopped by a uniformed official when “sneaking” in through the front gate. This particular Checkpoint Charlie is either unmanned or admits people no problem. (I’m similarly surprised when I can enter Fort Totten in Bayside, closer to home, unimpeded. Indeed, the only remaining active Army base in NYC is Fort Hamilton, just across the Narrows in Brooklyn, and things are considerably tighter over there.) Here McClean Avenue becomes Battery Road.

Fort Wadsworth

The southeastern tip of Staten Island, its closest approach to Long Island, has been protected by fortifications since 1663, when a Dutch blockhouse was established. The area was known as Signal Hill during the colonial period and the Revolutionary War: this was a crucial site from which to spy approaching British vessels.

Well into the 1970s, Ft. Wadsworth was considered the oldest continuously staffed military post in the USA. In September 1995 the fort became part of the National Park System; its grounds and military museum are open to the public. However: part of it is still used by the Coast Guard, and those parts of the grounds are closed to the public. A designated 1.5-mile trail winds past both Battery Weed and Fort Tompkins (see below). Call (718) 354-4500 for general information and hours. Access may be restricted during the Covid Crisis.

This handsome cottage is just inside the gate on Battery Road. There are a great many domiciles and residences on the Fort Wadsworth grounds, and official literature, both on what I found at the office and online, are tight-lipped about their current and past purposes.

This is the US Army Reserve Center on Battery Road, which has been unused for that purpose since the fort ceased operations in 1995. But what is the building’s purpose now?

Edward Findlay in Comments:

…”the US Army never actually left the fort, the US Army Reserve has had units based out of the former fort since transferring it to the US Navy and saw units activated multiple times over the past 41 years. The buildings they were using received renovations or were built new in 2011, with the facility serving as a base for the Superstorm Sandy relief efforts for months after the storm.

The only unit that I could find info on are the 961st Transportation Detachment and the 353rd Civil Affairs Command which are both based out center, but there’s probably smaller units out of there as well.”

Fort Wadsworth; its neighbor in Rosebank, Von Briesen Park; and Shore Road Park in Bay Ridge, perhaps enjoy the choicest views of the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Between 1959 and 1964, I watched as the bridge was built practically in my “back yard” in Bay Ridge. In the last decade, the bridge gained a “z” as documents from the 16th Century showed that explorer/mercenary Giovanni da Verrazzano‘s name was most often spelled with two.

Tompkins Street runs along the north side of the Verrazzano Bridge to the fort’s waterview area. Many Staten Island streets are named for Daniel Tompkins (1774-1825), James Monroe’s Vice President and the founder of Tompkinsville, several miles west; he built Richmond Turnpike, designed as an express route to Philadelphia, crossing the Arthur Kill by ferry: it is known today as Victory Boulevard.

On the right are seen the remains of Battery Duane, which was in use between 1895 and 1915. It was constructed as part of the Endicott Defense System and carried five 8-inch diameter rifled guns that were mounted on “disappearing” carriages that could retract behind the concrete wall after they were fired. They were never used in defense.

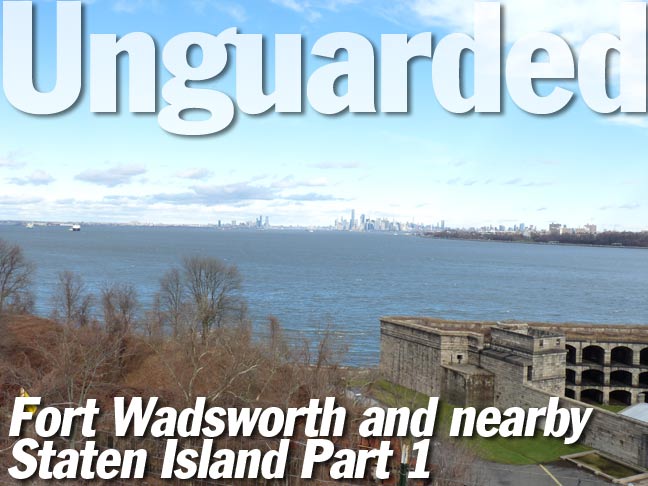

Battery Weed (Fort Richmond, renamed in 1863 for General Stephen Weed after his death at age 29 at Gettysburg), was designed by the US Army’s chief engineer, Gen. Joseph G. Totten, and was built between 1845 and 1861. From the vantage at the fort’s Tompkins Street and Hudson Road, it forms a spectacular foreground to not only the Verrazzano Bridge, but also the distant Manhattan skyline and even Jersey City on the other side of the Hudson.

Battery Weed’s tiered design permitted 118 guns to aim cannonballs across the Narrows. However, by 1863 heavier munitions had been designed that could easily breach and destroy fortifications like this. The base was named Fort Wadsworth for Gen. James S. Wadsworth, an 1862 NY State gubernatorial candidate who served with distinction at the battles of Bull Run, Fredericksburg and Gettysburg and was killed at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. Staten Island’s and Manhattan’s Wadsworth Avenues also bear his name. Battery Weed was named for Brigadier General Stephen Weed, who was killed at Gettysburg.

Zooming into the skyline across Upper New York Bay.

Accessing Battery Weed and seeing the drill space and gun emplacements — complete with cannon — is an unforgettable experience and we were able to do just that during June 2019’s Forgotten NY tour with the aid of a park ranger from the Fort Wadsworth office (forgive me, but I have forgotten her name). The ranger also granted us access to the Mont Sec House (see below). Photos: Bob Mulero

Fort Tompkins, the second fort to carry the name here, was built between 1859 and 1876 of granite, brick and sandstone. It carried only one gun and was not constructed with defense in mind; rather, it contained barracks for soldiers, and military drills were conducted there.

North Weed Road descends a steep hill toward Battery Weed. Along it you will see the remains of the much smaller Battery Catlin, which was basically a lookout designed to allow officers to observe accuracy of shells fired from nearby batteries. Instructions would be given by telephone to gunners to adjust their aim when necessary. The battery was constructed in 1904 and did have six 3-inch rapid-fire guns installed in 1913, fired only for practice; these were removed in 1942.

This is Ft. Wadsworth’s former torpedo manufactring center and wharf. In the 1800s. the term “torpedo” did not refer to bombs fired by submarines; they were mines, as in “damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead.” On the wharf, built in 1850, the mines were loaded onto vessels for placement in New York harbor. They were carried on railcars from the factory to the wharf, and the tracks the cars traveled on are still in place. Since no enemy vessels entered the harbor during the Spanish American war or World War I, the system remained unused.

You read that right. At times, the National Park System brings in goats as living vacuum cleaners to clear the thick weeds and other vegetation found on the steep hills. Goatherd Larry Cihanek from upstate Rhinebeck draws a 6-figure annual take from various agencies who employ his goats to get rid of weeds.

South Cliff Battery was established south of Battery Weed in the late 1890s and supported nine 15-inch diameter Rodman guns, the largest guns in active use at the time (though none was fired from here in wartime). By comparison, the huge Rodman gun in John Paul Jones Park in Bay Ridge is a 20″ gun that was deemed impractical. Nearby Bacon, Turnbull and Barbour Batteries supported 3″ rapid-fire guns.

Fort Wadsworth’s chapel is named for Father (Vincent) Capodanno Boulevard was named for a Staten Island priest who won a posthumous Medal of Honor for his actions under fire during the war in Vietnam in 1967. Seaside Boulevard, a main highway along South Beach, was named for him in the 1970s. Protestant, Catholic and Jewish services are held on Wednesday and Sunday.

Mont Sec House

The eleven houses along Mont Sec Avenue were once the homes of Fort Wadsworth officers and their families. The oldest house, #103, dates back to the 1870s. Houses #111-114 were built around 1890. The rest were built in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration, which was part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal that was designed to help the economy emerge from the ravages of the Great Depression.

House 112A is known as the Mont Sec House, seen above. Once again, our ranger was kind enough to let is in and roam about for a bit on the Forgotten NY tour. This home has been restored by the National Park Service and furnished as it might have been in the 1890s. It is open to visitors on a very limited basis. The interior reminds me of Theordore Roosevelt’s Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay. Mont Sec is named for a WWI battlefield. Photos: Bob Mulero.

It wouldn’t be Forgotten NY if I didn’t mention the street lighting. Fort Wadsworth has a mix of new LED fixtures (very small ones, not used elsewhere in NYC) and older mercury lamps. And a leftover or two…

Here’s an intact Gumball fixture at the west gate at Bay Street and Wadsworth Avenue. No idea if it works or not; if it does, it has an incandescent bulb. This is a lamp that has simply been overlooked.

There are also a pair of older street signs; in Fort Wadsworth, Bay Street becomes New York Avenue which is actually its former name in Rosebank, the neighborhood that adjoins the fort. I’m not sure whether Fort Wadsworth’s streets should be listed in the regular NYC street directory, now that the fort is basically a park. I would lean against it because of precedent. Large cemeteries such as Green-Wood, Evergreens and Woodlawn have their own streets (that don’t have addresses) and those streets aren’t counted in the NYC gazetteer.

Rosebank

Above: St. John’s Church; houses along Bay Street

Formerly Peterstown, in the 1880s the neighborhood north of Fort Wadsworth came to be called Rosebank presumably for an abundance of rose bushes and its location on the shore. It has always been known for its Italian population, as immigrants began arriving here as early as the 1880s. The present population numbers about 16,000. A substantial part of the shorefront east of Bay Street was taken up by a maritime quarantine station from 1873-1971; the site is now occupied by Coast Guard housing.

Beautiful views of the Narrows, the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, and Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, can be glimpsed from Alice Austen and Arthur Von Briesen Parks. Rosebank is anchored by the campanile of St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, built in 1857 at 1101 Bay Street at St. Mary’s Avenue (sadly, the parish has recently been eliminated), and the slim spire of St. John’s Episcopal Church (above) built in 1871 at 1331 Bay Street opposite Belair Road.

The Woodland Cottage, 33-37 Belair Road, is a designated NYC Landmark. It was constructed in 1844 as part of a real estate development, one of a number of Gothic Revival small to medium size residences built in the same era. The detailing is reminiscent of the work of Alexander Jackson Davis although the architect is now unknown. There is an addition, ca. 1900, added late that is out of the picture on the western end of the building. The Woodland Cottage served as the rectory of St. John’s Episcopal Church from 1858-1869. photo: Emilio Guerra

There are other Gothic cottages on Belair Road between Bay and Clayton Streets, but none have Landmarks protection and have been subject to various alterations by their owners. Still, the original appointments can be seen here and there.

One of the most identifiable remnant of the old Staten Island Railway, formerly Staten Island Rapid Transit, can be found at St. John’s Avenue and Clayton Street — a stone wall stamped with the date 1936. The railroad once passed here north of the Belair Road station. SIRT service to Clifton, Rosebank, Arrochar and South Beach in 1953, and gradually, all trace of the railroad in the neighborhood has otherwise vanished. The line was originally built at grade and elevated on a trestle in 1936, hence the date. It survived only 17 years after that. A station was located at Belair Road.

Check musician Gary Owen’s SIRT South Beach Line page for choice images of a bygone era in Staten Island rail service.

Indulge me while I do a bit of infrastructural comment here in Rosebank. The main north-south streets are Bay Street and Tompkins Avenue, while no other north-south route extends for more than a block or two—except for Anderson Street, which goes a good 8 blocks between Lynhurst and St. John’s Avenues. But the street is hardly continuous. It stops and starts so that a motorist who wanted to stick to it would have to jog a bit on Hylan Boulevard and Maryland Avenues to stay with it.

The answer can be found in this 1917 atlas plate from the New York Public Library that shows the original section of Anderson Street was the one block between Pennsylvania Avenue (now Hylan Boulvard) and Clifton Avenue. The other seven blocks were added to its north and south.

As an aside: I find the NYPL a valuable resource, but I dislike their “zooming” policy. You can get a good look, but you can only zoom in so far, because they want you to actually buy the map plates they’re offering. I know, commerce. As a researcher, I just find it inconvenient.

Walking down Anderson Street reminds you that not so long ago the area was still rural, as there are large empty lots on either side at Virginia Avenue.

At Hylan Boulevard and Anderson Street, there’s an apparent infrastructural redundancy as a cylindrical post has a mounted “pedestrian control” signal, while an iron post next to it carries the one-way and no-parking signs. The cylindrical post could have handled everything, but the Department of Transportation installed two posts to do the work of one. Using Street View, I deduced that the situation was the same as long ago as 2007. What happened was likely one post preceded the other.

Kaltenmeier Lane is a short, one-block road between Anderson Street and Tilson Place, north of St. Marys Avenue. It is unlit by a streetlamp and has no sidewalks and only two addresses on it. In the past the Department of Transportation has had trouble spelling it but they seem to be getting it right now with new and old signs. However: Open Street Map is struggling with it. At 11 letters, it is tied with another nearby short street for the neighborhood’s longest street name (see below).

This brick building illustrates Rosebank’s past and present as an Italian-American enclave. The former “Ignazio Rosso & Bro. Staten Island Macaroni Corporation” at #100 St. Mary’s Avenue now houses medical offices.

The parish of St. Joseph at Tompkins Avenue and St. Mary’s Avenue dates to 1901 and was established by Father Paolo Iacomino that year (for a photo of the original church see this page). The present edifice was built in 1957, same year as your webmaster. The carillon tower looks newer than 1957.

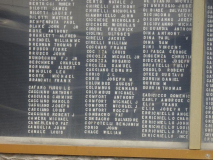

The Rosebank Honor Roll, on Tompkins Avenue across from St. Joseph’s Church on Shaughnessy Lane, celebrates Rosebank residents who served in World War II.

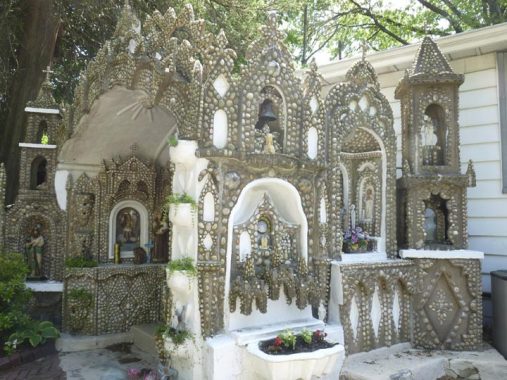

Shrine of Mount Carmel

No visit to Rosebank is complete without a visit to this remarkable tribute to faith built by the Society Of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, completed in 1938; the society maintains it today. Founded in 1903, it is one of a number of mutual aid societies formed by Italian immigrants in the early 20th Century, offering benefits and organizing religious feasts and ceremonies. I was last here in 2008 (that year I composed a page dedicated to it), but every time I’m here I can’t stop snapping photos, hence the unusually large photo gallery. All the shrines and icons in the grotto are constructed with small stones and rocks encased in concrete.

The Shrine isn’t the easiest tourist attraction in the borough to reach. From Tompkins Avenue, going ferryward, turn left on St. Mary’s Avenue, then turn left again at White Plains Avenue, then right on Amity. The grotto is at the end of the street on the left.

Next: Rosebank into Clifton and Stapleton

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

5/10/20

7 comments

I remember when I was a kid from Bay ridge we would take the bus over to fort Wadsworth. There was a rope that hung down and I think the second or third story and we will climb up it and explore the fort. Long before it was a national park. Years later I actually met Larry he owns the restaurant in the beekman arms and Rhinebeck New York. What a great guy

I was able to zoom way in using fingers in that Bromley, on my phone. To the level of an individual property basically filling

the screen. Enjoyed the tour.

I was born and raised in Fort Wadsworth & Rosebank,S.I. I been through everyone of those places so many times I can’t count.

You are actually wrong about that army building being abandoned since 1995: the US Army never actually left the fort, the US Army Reserve has had units based out of the former fort since transferring it to the US Navy and saw units activated multiple times over the past 41 years. The buildings they were using received renovations or were built new in 2011, with the facility serving as a base for the Superstorm Sandy relief efforts for months after the storm.

The only unit that I could find info on are the 961st Transportation Detachment and the 353rd Civil Affairs Command which are both based out center, but there’s probably smaller units out of there as well.

My Defense Department job was relocated (around 1995?) from the Federal Building at corner of Varick and Houston Streets to Fort Wadsworth to save money. We were in the building that serves as the Park Service HQ. I remember daily walks around the post…there was a lot of vacant family housing built for the Navy’s Homeport that never happened.

Fort Wadsworth…home of the world’s longest urinal (350 feet!, set up each year for the start of the NYC Marathon).

I great piece, as usual. One minor error. Tompkins was VP under James Monroe, not Madison. Madison had two VP’s: George Clinton, who he inherited from Jefferson, and Elbridge Gerry. Both Clinton and Gerry died in office. While Tompkins, who had a pretty big drinking problem, made it through both of Monroe’s terms, he died a few months after leaving office. He is buried at St. Marks Church in the Bowery. So being a VP then was not good for your health.

noted