This article is an expanded version of a SpliceToday post from December 9, 2020.

A post-Thanksgiving trip saw me heading up Vernon Boulevard from Hunters Point to Ravenswood. At the spot where I began, Vernon Boulevard widens considerably from 50th Avenue to Borden Avenue and gains a concrete mall. The reason is that this spot has formerly been the location for a succession of bridges that crossed Newtown Creek from Hunters Point to Greenpoint, the first built in 1840 by the Ravenswood, Hallett’s Cove and Williamsburg Turnpike and Bridge Company (that also constructed Vernon Boulevard along the shoreline). In 1903 that bridge was replaced by a swing bridge across the creek, but the bridge was doomed when the Pulaski Bridge was built in 1954. Earlier the Kosciuszko Bridge had spelled the end for Penny Bridge, which connected Meeker and Review Avenues.

Here we see Vernon Boulevard looking north at 50th Avenue in Hunters Point, Queens toward the steeple of St. Mary’s Church. St. Mary’s, at Vernon and 49th Avenue, was built in 1887 and designed by famed church architect Patrick Keely. St. Mary’s, with its distinctive clock steeple, was the tallest structure in Hunters Point for over a century until the Queens West development of the 1990s set off the current spate of glass-clad residential skyscrapers in the blocks to its west. The church is built from brick and brownstone in a simple Gothic design, featuring multiple pointed arches across the façade on Vernon Boulevard, and a tall steeple that rises several stories. Clad in gray slate, the steeple houses clocks on each side, and marks the skyline as it rises over the boulevard.

Who Was Vernon?

By BOB SINGLETON

Director, Greater Astoria Historical Society

Ebenezer Stevens, born on August 11, 1751 in Roxbury, Massachusetts, died on September 2, 1823, in Rockaway, New York and is buried in Astoria. He was a lieutenant colonel in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, a major general in the New York state militia in the War of 1812, and a New York City merchant.

His training as an officer in the artillery gave him an unparalleled opportunity to be at more pivotal points of the Revolution than anyone, excepting perhaps only George Washington. His distinguished record included Bunker Hill, the British surrender at Saratoga, and war’s end at the Siege of Yorktown. He served with distinction under Nathanael Greene, Marquis de Lafayette, and George Washington.

It was after fleeing from the Boston Tea Party that he found shelter with his friends, Samuel and William Vernon, merchant bankers of Newport, Rhode Island, and leaders in the resistance to the taxation policy of Britain. He would never forget their kindness.

At war’s end Stevens moved to Astoria purchasing much of the Hallett Farm they lost as a penalty for supporting the British. He was also one of the first to see the Treaty of Paris (ending the War of Independence) as it was delivered to New York, then the seat of government, by neighbor John Delafield.

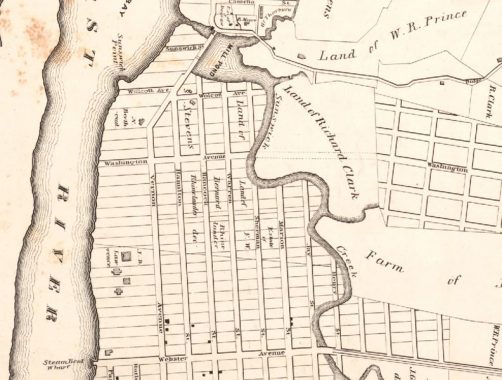

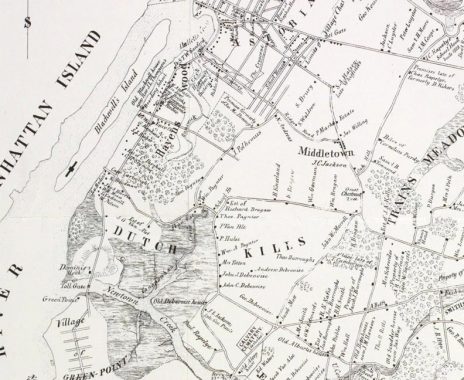

The first decades of the Nineteenth Century was a time of rapid growth where farmland transformed into blocks and lots and meandering country lanes into turnpikes directly linking communities. In the budding neighborhood of Ravenswood, the location of Steven’s farm, he plotted streets named for Revolutionary leaders: Warren, Hancock, Hamilton, Washington, Marion, Jay … and as a tribute towards his friends at the beginning of his career, Vernon.

‘The Ravenswood, Hallett’s Point and Williamsburgh Turnpike Road & Bridge Company,’ with the backing of Astoria’s Stephan Halsey, was chartered in 1838 to connect the Village of Astoria with the City of Williamsburgh in Kings County. It had the first bridge over Newtown Creek linking Hunters Point to Greenpoint. Until the charter expired in 1868, the toll house at either end was entitled to a fee derived from a somewhat overly detailed fee structure base on a dizzying array of conveyances and types of traffic (animal or human).

It never seemed to be well run or make a profit, but it did cement an important link between Astoria and Brooklyn to a family whose identity is all but forgotten. It ran along the right of way, dubbed on old maps as ‘Vernon Avenue’, its name until the 1920s, when it became Vernon Boulevard.

Sadly, the decades-old Dorian Cafe at Vernon Boulevard and 50th Avenue closed in December 2019. Some CBC crime dramas had filmed in its interior, and it had hosted the “postgame show” for a Forgotten NY Hunters Point tour in 2018.

On the east side of the Vernon Blvd. Mall at 10-10 50th Avenue we find the vestiges of the Vernon Theatre, a small (550-seat) second-run picture house that opened in 1922 and lasted until 1957, when its last feature was The Incredible Shrinking Man.

This is a fairly new addition on 50th Avenue just east of Vernon Boulevard. Underpenny Museum is a junk shop, but it also bills itself as a museum of kitsch, a tribute to ephemera, in the vein of the City Reliquary in Brooklyn. Inside you’ll find rare art, sculptures, jewelry, and most notably, a large collection of 19th– century cast-iron pieces. Some is for sale, but some is on exhibit only: hence the “museum” moniker.

I was tipped about this ancient sign at 49-10 Vernon Boulevard in the recent book by Bill Helmreich, The Queens Nobody Knows (sadly, Helmreich, who I met by serendipity on a tour in Fordham in 2018, passed away in 2020). The family of Italian immigrant Antonio Mora marks the spot at #69 Vernon Avenue, now 49-10 Vernon Boulevard, where Mora maintained his coal and ice business after immigrating from Italy in 1897. How long this sign has been here, I have no idea, but I never noticed it on previous trips down Vernon Boulevard, which have been often.

Notice the telephone exchange, HUnterpoint 0677. By 1940, the Monas were operating a clothes cleaning business at 49-10.

A sidewalk sign sampler along southern Vernon Boulevard. The Societa Sant’ Amato di Nusco was founded early in the 20th Century by immigrants from Nusco, Italy, offering aid, financial and otherwise, to Italian immigrants prior to the establishment of Social Security or Medicare. Meanwhile, the restaurant Bellwether is named for the lead sheep in a flock (who were often belled; the word came to mean a trendsetter or predictor). Outsect, which keeps a lot of toys in its window, is an exterminating business, as you might expect.

Vernon Boulevard looking north at about 48th Avenue.

Until the 1990s, Vernon Boulevard was bridged over a LIRR railroad cut leading to what is now Gantry State Park on this truss bridge. The bridge was demolished and the west end of the cut was filled in, becoming a park and athletic field.

February 1983 photo of the Vernon Boulevard truss bridge by Bill Mangahas.

Sweet Chick, a Southern chicken and waffles franchise, paints its sidewalk signs right onto the building bricks. LIC Bar recycles an older neon sign and employs new gold leaf window print.

47-02 Vernon Boulevard is one of my favorites along this stretch, which features a number of handsome brick walk up buildings. 47-02 is augmented with green window lintels and corner quoins.

44th Drive is the widest east-west street in southwest LIC and even has a center median in some spots. The glass jungle of Manhattan in the East 40s can be seen here, including the UN Secretariat Building, Chrysler Building and Trump International, formerly the tallest residential building in the country.

44th Drive, when it was laid out in the mid-1800s, was named for Eliphalet Nott, inventor of the anthracite coal stove and founder of upstate (Schenectady) Union College. Nott, along with Neziah Bliss, had purchased the estate of the Hunter family, which owned the territory, in 1835. Bliss set about founding Hunters Point, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and a small eastern hamlet called Blissville.

Talking Heads are perhaps more associated with the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, where the band originated, or the Lower East Side, where they made their name in the club scene of CBGB and the Mudd Club. However, they’re associated with southwest Long Island City as well. The band practiced in this industrial loft building until 1979 at 9-01 44th Drive at Vernon Boulevard, and bassist Tina Weymouth and drummer Chris Frantz lived in the building in 1976-1977.

This crossroads was slated to be the site of a large Amazon office complex before pressure from local politicians forced a change of plans.

North of 44th Drive, Vernon Boulevard’s aspect changes considerably from residential/retail to industrial; any residential buildings along the road are in housing projects from here north through the neighborhood of Ravenswood.

At 43rd Avenue and Vernon Boulevard is an ivy-covered brick building home, on the 43rd Avenue end to DuVal Enterprises, which develops the interior spaces of this former metal foundry for magazine and video shoots. It’s divided into three separate areas: The Foundry, The Terrace and The Loft.

The Foundry is a 19th Century building where originally fine varnishes were manufactured [by Emil Calman and Co.] before it housed the Albra Metal Foundry. Their logo is still visible on the corner of the building at 9th Street and 43rd Avenue [hidden by foliage during the summer.] It’s hard to make out because of the ivy, but the name “Emil Calman & Co.” can still be made out on the Vernon Boulevard entranceway.

By the 1970’s The Foundry was essentially an abandoned space, housing defunct vehicles and a mountain of debris. In 1980 the Du Val family purchased the property. The family restored and renovated the space to reflect its original industrial character, and began using it as an event space in 2001. It is the only foundry in the area still standing today.

Across 43rd Avenue, Big Alice Brewery, named for the local Con Ed plant (see below) was founded by Kyle Hurst and Scott Berger in 2013. Dozens of craft beers, brewed on premises, are offered here. Seating is available in non-pandemic times.

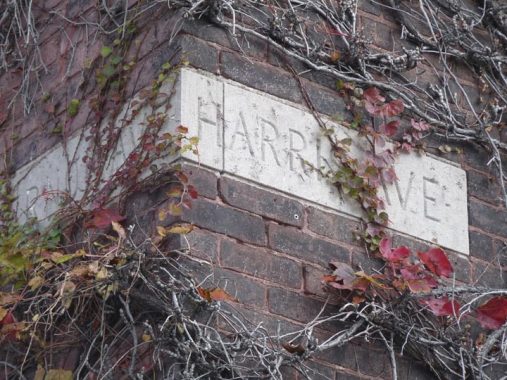

Meanwhile, at the corner of Vernon Boulevard and 43rd Avenue we see a remnant of Queens’ pre-numbering when most streets had an actual name.

This excerpt from a 1922 Hagstrom map shows 43rd Avenue as Harris Avenue. Also note Van Alst (21st Street) and Ely (23rd Avenue) whose names survive, improbably, in NYC subway stops.

Over a century after its opening, the name of this bridge is disputed. Officially the Queensboro, designed by Gustav Lindenthal and Henry Hornbostel, it opened to traffic in October 1909. Since March 2011, the bridge has been officially known as the “Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge,” gaining the name before the three-term mayor’s death in February 2013. The bridge was renovated in stages from 1987-2012. I have rarely been on the bridge — the only occasions I can recall are on a bicycle, during the 5-Boro Bike Tours I participated in, from 1984-1987, 1990, and 1999.

The bridge also has a third name: the “59th Street Bridge,” as made plain to the rest of the country by Simon & Garfunkel’s “59th Street Bridge Song,” which was a hit in the USA by Harpers Bizarre. What I don’t know is: how the name of the bridge breaks down between Manhattanites and “Queensicans.” My thinking is, Manhattan people call it the “59th Street Bridge” and Queens people call it the Queensboro. I could be wrong, though! The floor is open in Comments.

I know one thing. Only the Department of Transportation calls it the Ed Koch Queensboro…on official highway signs.

The Queensboro was instrumental in the conversion of Queens from a primarily rural country dotted with small towns to a fully integrated borough of Greater New York. The Bowery Boys tourguides and authors make this plain in their January 2021 podcast.

The New York Architectural Terra Cotta Works was established in 1886 by James Taylor, who was fresh off successes in the Boston firms Lewis and Wood and the Boston Terra Cotta Company (he was a steamroller, baby). The New York works would go on to produce terra cotta for Carnegie Hall and the Ansonia Hotel. While Taylor died in 1898, his NYC terra cotta works would continue to thrive until 1928. Its small office/showroom building, built in 1892, still stands at 42-10 Vernon Blvd. The little brick building has been landmarked, and recently the exterior was rehabilitated by Citigroup, revealing even more incredible detailing, but any future uses for the building are still undetermined.

On the exterior you can see the date of construction (anno Domini 1892) and the original address (401, which was on Vernon Avenue).

This would be a great spot for a museum or visitors center, but it’s in a precarious spot that gets little foot traffic (though decent bicycle traffic) and is located between two power plants, making public access to it unlikely to gain approval from officials.

You may think that Queensbridge Park, which stretches along Vernon Boulevard from the bridge north to where 40-15 Vernon would be, might be called Queensboro Bridge Park (ditto the Queensbridge Houses across the street). However the Powers That Be apparently wanted something shorter.

Both the park and the Houses were opened in 1939. The park is characterized by a variety of facilities, including baseball fields, a soccer-football combination field, basketball, volleyball and handball courts, a playground with see-saws, swings and jungle gyms, a comfort station, picnic areas, sitting areas, walkways, greenery, and trees. In 1994 the waterfront was reconstructed and riprap (large cut boulders) were added as a seawall. The park’s original 1941 fieldhouse survived until 2018 when it was replaced with a state of the art facility with restrooms, conference rooms for Parks personnel, and maintenance storage. The park boasts fine views of both the Queensboro and the Roosevelt Island Bridge, seen on this FNY page.

The Queensbridge Houses are the largest of Queens’ 26 public housing projects, and indeed the largest in North America. Approximately 7000 people live there. The Houses are bordered by Queens Plaza North (at the bridge), 40th Avenue, 21st Street and Vernon Boulevard and are bisected by 41st Avenue. If you are riding the N train to Manhattan from Queensboro Plaza, you can see them out the north facing side of the car before it enters the East River tunnel. Beginning in the 1980s, the Houses have been home to some of the country’s most prominent rappers including Nas and the duo Mobb Deep.

Showing one of the Houses’ original blue enamel directional signs.

“Big Allis,” officially known as the Ravenswood Generating Station, at Vernon Boulevard and 36th Avenue, provides 21 percent of the electricity consumed by New York City. It was constructed by the Allis-Chalmers Corporation; when it opened in 1965, it was the world’s first million-kilowatt power plant. It has been owned by several: Con Edison, then Keyspan, National Grid, and TransCanada since 2008. Its red and white smokestacks can be seen for miles in Queens and Manhattan. The plant sits on the former location of the 1744 Blackwell Mansion; the northwest Queens colonial-era family also originally owned what we now call Roosevelt Island.

The Roosevelt Island Bridge is the only means of vehicular entry onto the island. Until its opening in 1955 the only means of getting to Roosevelt island were by boat; a trolley line also stopped on the Queensboro Bridge and an elevator allowed passengers to enter the island which, until the mid-1970s, was home only to hospitals.

A Vernon Boulevard sampler north of the Queensbridge Park and Houses.

This expansive riverside park between Vernon Boulevard, the East River, 33rd Road and 34th Avenue is named for a local resident who worked tirelessly for the construction of the Queensboro Bridge.

Dr. Thomas Rainey had been one of the earliest and staunchest supporters of the project, and the burden of organizing and refinancing the company fell on him, first as treasurer in 1874, then as president in 1877. Dr. Rainey lobbied around the country to get financial backing and a bridge franchise. However, the War Department, concerned that a bridge could interfere with the defense of New York and access to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, withheld approval. Most interest in the region was for another bridge between Brooklyn and Manhattan. The sparse population in Queens at the time raised further concerns of need and profitability, and the project had once again lost steam by 1892. NYC Parks

A group from the community called the Committee of Forty kept the effort alive. After the consolidation of New York City in 1898, the project gained new momentum and the bridge was finally built at Queens Plaza, a few blocks south of the proposed location. Rainey crossed the new Queensboro on opening day in 1909 with Governor Charles Evans Hughes.

The city acquired land here, at what was originally going to be the Queens bridge landing, in 1904 and designated it for a public park, which opened in 1912.

Leaving the park, I saw this dark gray brick building, and a truck in the parking lot, with “Kraus Hi-Tech Home Automation.” All these systems come with a red button that one should never press.…

At Vernon and 33rd Road you will find a museum dedicated to Japanese-American expressionist sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988). Though born in Los Angeles, Noguchi spent most of his childhood in Japan before attending Columbia University to study sculpture. Among his more notable works are the bridge in the Peace Park in Hiroshima, sunken gardens for the Beinecke Library at Yale University at New Haven and Chase Manhattan Bank in Manhattan, the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden in Jerusalem, and Moerenuma Park in Sapporo, Japan. Noguchi also designed stage sets and furniture pieces.

250 of Noguchi’s works are on permanent display here, including stone, bronze and wood sculpture, “Akari” paper and bamboo light sculptures, his sets produced for choreographers Martha Graham and George Balanchine, and an outdoor garden.

Named in tribute to its proximity to Greek-flavored Astoria, this waterside area along Vernon Boulevard between Main Avenue and Broadway was a dumpsite until it was “rescued” in 1986 by a coalition of artists/activists headed by Mark di Suvero. The Socrates Sculpture Park now works both as an outdoor workshop for aspiring artists and as a waterside park. Exhibits change frequently but a recent visit revealed works by sculptors Paul Ramirez Jonas, Sandy Williams IV, Xaviera Simmons and Jeffrey Gibson.

Where the park sits now was once above a creek running between the Queens Plaza area and emptying into Hallett’s Cove. A grist mill—the first one was built in 1679 — once stood in the Socrates Park area and in 1957 workers discovered two millstones and Spanish pieces of eight dating to 1797. Unlike the two millstones belonging to the Payntar farm which are displayed at Queens Plaza, the whereabouts of the two millstones found here are unknown.

Dos amigos. The Chrysler Building (1930) and Empire State (1931), two of NYC’s earliest entries in the Supertall Sweepstakes, can be seen looking south on Vernon Boulevard from the park.

The Hallett family, led by patriarch William Hallett, emigrated from England and settled in Greenwich, Connecticut in 1648, but moved in 1652 to 160 acres in the Hallett’s Cove area of Astoria. In 1664, William Hallett expanded his holding to 2,200 acres, which included all of modern-day Astoria. Williamhallett.com

The LIC Community Boathouse offers free kayaking and canoeing in Hallets Cove, an indentation of the East River just north of the sculpture park.

Vernon Boulevard’s most venerable structure may be the former Sohmer Piano factory, 11-31 Vernon at 31st Avenue.

I first encountered the building several years ago when it was still occupied by the Adirondack Chair Company (their ad can still be seen on its south side) and spoke with John Pupa, Vice President of Operations for Adirondack. He said that Adirondack no longer heated the building with coal but it still maintained its old Hewes and Phillips coal-burning oven, which he showed me and GAHS Director Bob Singleton, and took coal deliveries. From one of the upstairs rooms, now converted to a condo apartment, we had a good view of the river, Roosevelt Island and its lighthouse.

It’s not the only piano factory converted to luxury in NYC of late — I was taken by surprise to discover that the fortress-like, hulking Steinway factory on Ditmars Boulevard and 45th Street in Astoria became the Pistilli Grand Manor, and the clock-towered Estey Piano building and its distinctive clock tower in the Bronx’ Mott Haven became residential in the early 2000s. Sohmer pianos? They are now manufactured in Korea.

A pair of chiseled signs at Vernon Boulevard and 31st Avenue proclaim the former names “Boulevard” and “Jamaica (Avenue).” However I do not have maps with these former names. In 1886, when the factory was constructed, those were no doubt briefly the names; Jamaica Avenue later became Patterson Avenue and then 31st.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

1/17/21

8 comments

I worked in a NYC Board of Education building at Vernon and 44th Drive from 1984 to 2002. On paydays we’d often have lunch at one of several taverns a few blocks south on Vernon. The strip from 47th to 50th Avenues had many options for food: pizza, Chinese takeout, coffee shops, and numerous delis and bodegas. Hunters Point had a heavy working class vibe during this time. In the late 1990s, the first high rises appeared on 48th Avenue, right around the time the truss railroad bridge was torn down. We knew the neighborhood was changing when bodegas started becoming “gourmet food shops”. (Similar semantic gentrification was hitting 21st Street around the subway stop at 44th Drive as well.) The huge apartment complexes that sprung up next to Gantry and Hunters Point South parks brought a similar crowd of young transplants that befell Williamsburg. The trusty Chinese takeout and pizzeria disappeared around 2016, and (except for a Dunkin’ between 49th and 50th) the eateries are largely “artisanal”, i.e. expensive, bizarre food.

My co-workers and I whose jobs were moved from the area in 2002 joke that the neighborhood got a lot better now that we’re not there anymore.

There are indeed multiple maps (dated between 1891 and 1913) that show Boulevard and Jamaica Avenue. They are available in the NYPL digital collections.

While Van Alst is still memorialized in a subway station name, Ely has lost that distinction having been renamed to Court Square.

tiled signs still say Ely

Mea culpa. I was thinking of the Crosstown line station. Been many years since I’ve taken a ride from/through the 8th Avenue-Queens Boulevard station of the complex. I would have guessed that the MTA would’ve standardized the name across all the stations in the complex by now. I guess that’s not the case.

I had a “question my sanity moment” a few years ago when I went down to Vernon and did not find the bridge. I said to myself- “I could have sworn there wasa bridge there once” and then found it in old Google photos.

I used to visit the food joints along Vernon between Borden ave and 47 st. There was the butcher, a deli with one of those buffet type of counter, weigh the food at the end. A pizza place, not sure of the name had a decent slice. Across the street next to where the bridge was a Chinese takeout that had good general tso chicken. A little further down was a deli, next to the amato society. St .Ann’s Church had 12:00 mass shortened for workers on their lunch hour. Dorian was there a long time. Had good burgers. Lillian hardware had wood floor and shelving that looked liked turn of the century. We used to buy from them, having parts and other items that weren’t available anywhere else. There were places that dealt with the industrial trade, selling belts and pullies. Much has changed since I worked at QMT. I saw the first hi rise along the river being trucked in section by section, many more to come, since 96 when I transferred out. The area seemed to be kind of artsy because of the loft space in the area.

Thank you for sharing these great pictures of the locations of my earliest memories. I spent the first 5 years of my life living in the Queensbridge projects in building 41-07 Vernon Boulevard. My 4 older siblings and I attended, and graduated from, St. Mary’s school. The school was on 49th Avenue just east of Vernon Boulevard, and is now the Herbert G. Early Childhood Center. Across the street from the school is still an empty lot which was our playground. The St. Mary’s Senior Food center, right near the empty lot, was the original convent. It became a Police Athletic Center (PAL) after the new convent was built – I don’t remember if the new convent was on 11th Street or Jackson Avenue; I believe it was built about the same time as the Pulaski Bridge.

Having frequently crossed the “Queensboro Bridge” from the Vernon Boulevard side, via the elevator to the trolley car, to Manhattan, I can tell you that we always called it the “59th Street Bridge”. On the Manhattan side of the bridge, the trolley went underground to a “loop terminal”.