Sergey’s recent piece on the Brooklyn Navy Yard reminded me of the street that I think has changed more than any other in New York City since the mid-20th Century. When I began perusing street maps as a kid in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I found Sands Street in the Cadman Plaza-Navy Yard area, and my brain immediately assumed it was called “Sands” since it was near the water (despite there being no beach in the area). Instead, the street is named for the Sands brothers, Joshua and Comfort, who owned much of the territory where the street sits in the colonial era. The wealthy merchants made their money in Brooklyn’s then-important ropemaking business and the Brooklyn Navy Yard was established on the former Sands holdings in 1801. Joshua Sands (1757-1835) became a US Representative, State Senator, and collector for the Port of New York [info from Brooklyn By Name, Benardo/Weiss]

On this page, I’ll discuss what we see today on Sands Street and then show you a bit of what it looked like in the past. I guarantee you’ll be shocked if you’re an area resident, or are familiar with the area as it is now.

When laid out in the early 1800s, Sands Street ran uninterrupted from Fulton Street between Middagh and Henry Streets due east to Navy Street, where there was, and still is, an entranceway to the Navy Yard. By 1899, though, partitioning had already begun when the Sands Street Elevated Terminal was constructed. It served as a choke point through which the great el train lines of Brooklyn on Fulton Street, Myrtle/Lexington Avenues and 5th Avenue were directed across the Brooklyn Bridge. The great shed also served as depot for many of the surface, or trolley lines that fanned out across the borough. El service across the Brooklyn Bridge ended in the 1940s, and the construction of Cadman Plaza doomed this great el train shed. If you have a Facebook account, you can see photos of it in the The Brooklyn Rapid Transit Els group.

Sands Street’s “deconstruction” continued in the 1950s, when ramps connecting the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway to the Brooklyn Bridge were built. Today, Sands Street begins at Adams Street, but the short stub shown above, signed by the Department of Transportation as Sands Street, goes to a fenced-off parking lot. It is located on Cadman Plaza East, itself a former section of Washington Street.

Note that arched-window building on the stub. It’s an old elevated train electrical substation, which is likely why this stub survived. See Comments.

Looking west on Sands Street from Pearl Street. Here there is a westbound Brooklyn Bridge ramp that has been here since the 1950s. There are also three original “Whitestone” type bridge lampposts, two Twins and a single. They have been rendered very scarce by the 2020s.

Trinity Park is a recreational area located under the BQE and bounded by Sands Street, Nassau Street, Gold Street and the Manhattan Bridge. It is named for the Trinitarian Sisters, a group of Catholic nuns working with the local Catholic Settlement Association of Brooklyn. The park was established when local buildings were acquired and condemned (see below) and received its present name in 1975. In the photo, you can see the bike path leding to the Manhattan Bridge.

Here we see the Manhattan Bridge approach crossing Sands Street at Jay Street. Subway tracks run on the bridge’s east and west sides, serving B, D, N, and Q trains as a rule, serving lines that run up Broadway and 6th Avenue. The 6th Avenue connection has been in place only since 1968; formerly, some trains turned south in Manhattan to the Chambers Street station beneath City Hall which now serves J and Z trains. The tracks’ position on the outside lanes proved to be a burden on the bridge, and wear and tear caused the tracks to be closed at various times for reconstruction for over a decade in the 1990s.

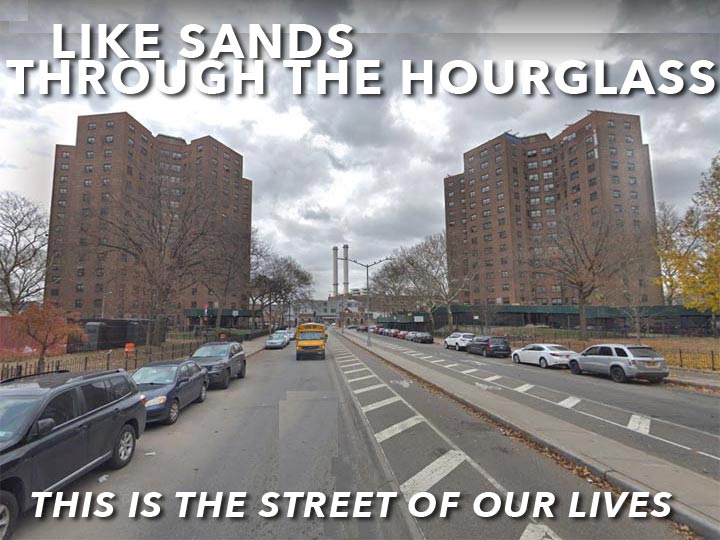

The Farragut Houses, named for Civil War-era Admiral David Farragut (“Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”) because of their position near the Brooklyn Navy Yard, were built on both sides of Sands Street by 1949, though land clearance began by 1945. However, the “superblocks” we see today, that necessitated the razing of hundreds of buildings and eliminating several streets and sections of streets) only appeared in 1952.

The Sands Street that was

Sands Street was a lively strip whose now-vanished saloons and gambling dens catered to sailors and workers from the neighboring Brooklyn Navy Yard. The WPA Guide to New York City, written in 1939, describes it thusly: “Today Sands Street caters to sailors and Navy Yard workers. Shop windows display outfits for sailors; bars and lunchrooms, quiet during the day, come alive at night as their customers arrive.” Sands Street, now dominated by Farragut Houses on each side, was once Brooklyn’s red-light district; these days, it’s almost eerily quiet, except when traffic is heavy.

Sands Street had been known as Brooklyn’s “red light district” and “Barbary Coast” for its brothels and bars. All that was swept away by Robert Moses and his expressways and Corbusian Farragut Houses of mid-century. However, the Municipal Archives of 1940 show Sands Street as it used to be.

37-39 Sands Street, just east of the Brooklyn Bridge. Two men chat outside M.S. Clothing Co., which was adjacent to Texas Lunch, one of the many bars and cafeterias along Sands Street. Odd numbered houses were on the north side of the street. Note that suits were going for $11.00-16.00. I’d have loved to be one of the photographers for this project. Unlike Google Street View of today, faces weren’t blurred out.

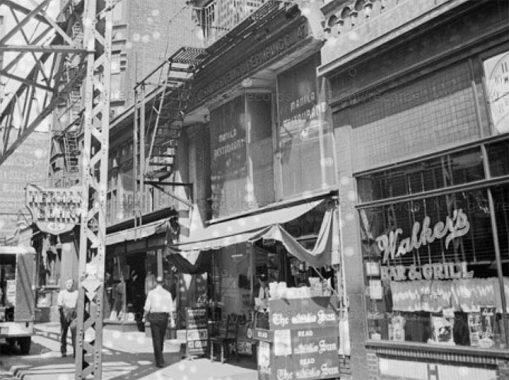

A few doors down was #47 Sands. If you look carefully at the windows on the second floor you can see the words “Manila Restaurant.” Sands Street was not only a haunt for Navy Yard sailors, it was also a Filipino stronghold. As I’ve said before, there are worlds within worlds. From the WPA Guide, again:

Around Sands and Washington Streets is a colony of Filipinos; native food, extremely rare in the eastern part of the United States, is served in a Filipino restaurant at 47 Sands Street. Among the favorite dishes are adabong baboy (pork fried in soy sauce and garlic); sinigang na isda and sinigang vitaya (fish soups); mixta [actually a Spanish dish](beans and rice); and such tropical fruits as mangoes and pomelos, the latter a kind of orange as large as a grapefuit.

In the 2020s, immigrants from the Philippines can be found in Woodside.

Note the elevated train pillars. The Myrtle Avenue El formerly ran from the Sands Street depot a couple of blocks east on Sands, then turned south on Adams, before turning east on Myrtle. The el was cut back to Jay and Myrtle in the 1940s and ended service in October 1969.

At the newsstand is labeled the [New York] Sun, a daily published between 1833 and 1950. A broadsheet Sun was revived between 2002-2008 and exists in an online version today.

Love Nest Candy, #50 Sands Street. Note the el turning south on Adams Street. The houses probably preceded the el, built in the late 1880s, and anyone living here had to acclimate themselves to the noise, especially in the warm months when windows were opened in the days before air conditioning.

Sands Street also featured light industry though not as much as in DUMBO, to the north. The Artistic Paper Box Company was on the other side of Adams, at #56. Scottish immigrant Robert Gair set up DUMBO’s corrugated paper companies in the 1880s, and the huge factory buildings are still there, now hosting many different businesses; I worked in an educational publisher, Amplify, in a Gair building in 2015.

The lamppost in the photo is an example of the Old Edison castiron post found exclusively in Brooklyn. None survive today. Note the “gumball” incandescent lamp and globular fire alarm indicator.

#97 Sands Street, a 6-story building (undoubtedly a walkup) was on the NW corner of Jay and Sands. It likely predated 1909’s Manhattan Bridge, which barely appears on the right side of the photo. Once again, its residents had to acclimate themselves to additional traffic noise. A fairly new 12-story office building occupies this site today.

Note the trolley wires and tracks. Sands Street featured a number of trolley routes; east of the Navy Yard they ran on Flushing Avenue. All were discontinued and replaced by buses by 1950.

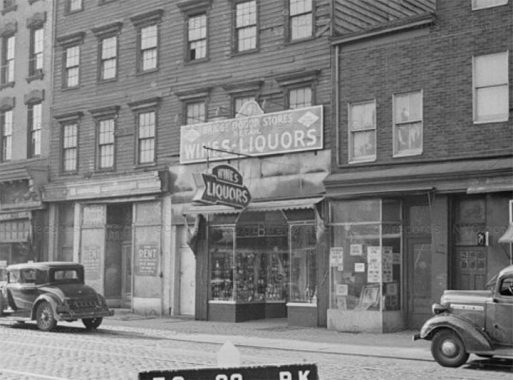

A liquor store at #141 Sands, just west of Bridge. The houses are wooden construction and must have been tinderboxes when inevitable fires occurred. Today there are a few woodframes left in Brooklyn Heights, but none are built today in NYC built-up urban areas; they’re just too risky.

#176-178 Sands Street, at the corner of Gold Street, was the Gold Theatre, open from 1927-1953, in the era when dish sets were given out to moviegoers (I’d like to know how that tradition got started). Note the adjacent multifamily buildings on the south side of Sands Street. Had NYC infrastructure czar Robert Moses permitted them to survive they would possibly be the heart of a thriving neighborhood. Instead, we got “towers in a park” in the Fab 50s. The intersection of Sands and Gold survives, but none of the buildings do.

Here’s an item at #181 Sands, just west of Gold, that shows that the term “bodega” is not a new one. The term refers to a convenience store run by Spanish-speaking residents. In early 2021, NYC mayoral candidate Andrew Yang was ribbed for visiting a convenience store that he referred to as a “bodega” though not all convenience stores are bodegas.

Note the Belgian blocked pavement and trolley tracks.

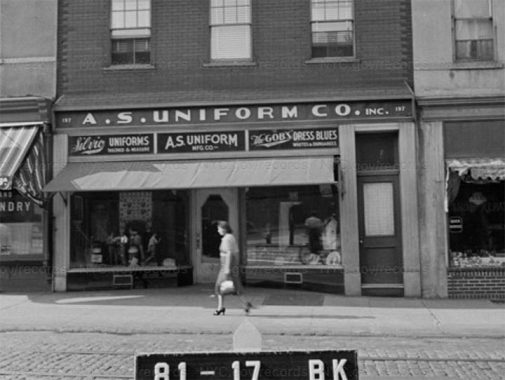

Outfitters and uniform shops were frequently located on streets near the Navy Yard. On Flushing Avenue, south of the Navy Yard, there’s still a ghost storefront for Reliable and Frank’s, which was in business for decades, becoming a typical “Army-Navy” sportswear store after the Navy Yard closed, until it went out of business in 2006.

Question: did enlisted men have to buy their uniforms? Seems to me they would simply be issued them. The floor is open in Comments.

There’s yet another outfitter seen on the left here, but the centerpiece of the photo is the Bohack’s at #203 Sands Street.

German immigrant Henry C. Bohack opened his first grocery in 1887 and over the years Bohack developed into one of the first powerhouse grocery store chains. Grand Union, Key Food and all the rest were to follow. When the Depression arrived in late 1929, Bohack responded by actually opening more stores to provide employment. The founder passed away in 1931.

Bohack’s prospered until 1974 when the chain went bankrupt. After an attempted merger with Shop-Rite failed, Bohack’s disappeared into the history books in 1977. Occasionally, though, an old awning or sign is taken down and the Big B is in evidence briefly once more.

The narrow lane on the right is Green Lane, which ran for 3 blocks from Sands north to Front east of Gold. It was obliterated in the 1950s for the Farragut Houses, as was the Bohack’s.

A bustling scene like this on Sands Street is somewhat unimaginable today; the corner building at Sands Street and Hudson Avenue, #223, is a 6-story walkup on the northeast corner.

As you may expect from what you’ve read, the further east on Sands Street, the closer to the Navy Yard you were, and the bars and taverns increase in frequency. Leo’s Bar and Grill had an immense neon arrow pointing to the corner entrance. You can’t see it too well but the cross street on the right side is a very narrow lane lost to history called Dixon Place.

On the other side of Dixon Place was a second dive, er, tavern, Joe’s Bar and Grill, at #235. Dixon Place may have served as a vomitorium in the old days.

Next door at #237 was a cafetria with a mighty neon sidewalk sign, with a literal clip joint next door.

On the south side of Sands Street, just before it reached Navy Street and the Navy Yard gates, was #228-236. The angled lane is the vanished Fern Place.

The Sands Street Y

One of two remaining buildings from Sands Street’s Navy Yard “heyday” is the former YMCA Naval Branch at #167 Sands Street. (The other is the substation mentioned previously.) It’s a magnificent Beaux-Arts building constructed in 1901-1902, a “gift of Miss Helen Miller Gould (Mrs. Finley J. Shepard) and Mrs. Russell Sage to the men of the Navy.” The presence of the US Navy and the YMCA bring to mind the 1970s group The Village People’s two biggest smashes “YMCA” and “In the Navy.” The building features some marvelously rendered sea-themed ornamentation such as a pair of fish over the front entrance and a pair of roundels with an anchor and six-oared sailing ships.

The building is now called “China Mansion,” a translation of the panels on the roofline. Its 120 residential units are, I presume, occupied by Chinese speaking residents and immigrants.

The laneway separating the YMCA and the Farragut Houses is the former Charles Street…

…as can be seen on this 1929 map excerpt.

Sands Street, in short, was exactly the sort of thing that the Robert Moseses and Le Corbusiers wanted to eliminate, and here, they succeeded beyond their dreams.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

2/11/21

18 comments

All military personnel are given a basic issue of duty and dress uniforms, footgear and other items of clothing when they first enter service. There is something known as a

“clothing allowance” which is a prorated amount of money included monthly in one’s pay. Over the course of the calendar year, the total is enough to cover the purchase of a

replacement duty uniform. If you need to purchase extra items like socks, boots, etc., the service member is on the hook.

If you want to see what Sands Street looked like before the projects obliterated nearly all traces, check out “The Tattooed Stranger”, a 1950 film noir that features scenes

filmed on Sands Street. Also, there is a book titled “The Pale Blonde of Sands Street” by William Chapman White which, as the title suggests, takes place on Sands

Street.

Joe: I couldn’t help but notice your profile picture. Wow, did anyone ever tell you that you have a very striking resemblance to Abe “Kid Twist” Reles? If you’re ever down in Coney, be sure to stay away from the Half Moon Hotel.

I lived on Sand & Gold St’s during WW2.

Great post.

In your first pic, the MTA building behind the fenced-in parking lot is much older than might appear. The arched windows are the giveaway – this is no ordinary garage.

It’s actually a repurposed electrical substation from the BRT’s elevated trains. The building was put up in 1903 shortly after the BRT was formed to consolidate the Brooklyn Heights Railroad and the other el lines. The 1904 Sanborn map labels it “BRT Substation No. 4.” The builder according to DOB filings was the mysteriously named “Transit Development Co.” which shared an address with the BRT on Montague St. (There’s a funny 1904 New York Times article titled ‘WANTED — AN EXPLANATION; Relations Between Transit Development Co. and B.R.T. Need Clearing Up” — apparently the BRT’s holdings seemed just as Byzantine to contemporaries as they do 120 years later.)

You can see some good pics of the substation building and its notable arched windows in the 1940s tax photos – check block 85, lot 9 (two different shots), and another view in the lot 12 photo. This last pic actually features more of the substation than the lot 12 building itself. (The Municipal Archives couldn’t figure out the substation address but according to the Sanborn it would’ve been 38-42 Sands St.) The substation is a few doors to the west of the Love Nest Candy store at 50 Sands in your pics.

Today you can get a good view of the original back of the substation building, which now abuts Red Cross Place. It had arched windows in the back, too, bricked up today. (Incidentally, until just now I had always thought as you write, that Red Cross Place might be a small vestige of High Street west of Adams. But in fact that’s not right – Red Cross Place is a new street that would’ve been in the middle of old block 85. This stretch of High Street would’ve been right where today is the northern edge of the current OEM HQ building. This is actually quite obvious from a modern map, I just had never bothered to look closely.)

The substation is the only building on Sands Street besides the YMCA building to have survived the BQE, Cadman Plaza and Farragut Houses redevelopments.

To me, even better than this old, hidden-in-plain-sight building is the street outside. Just off the corner of Sands and Cadman Plaza East (former Washington St), where you mention a curious Sands St sign still stands, is a manhole cover in Cadman Pl E that reads “BHRR” – for Brooklyn Heights Railroad. You can easily see the cover’s BHRR initialism in streetview.

Great post.

In your first pic, the MTA building behind the fenced-in parking lot is much older than might appear. The arched windows are the giveaway – this is no ordinary garage.

It’s actually a repurposed electrical substation from the BRT’s elevated trains. The building was put up in 1903 shortly after the BRT was formed to consolidate the Brooklyn Heights Railroad and the other el lines. The 1904 Sanborn map labels it “BRT Substation No. 4.” The builder according to DOB filings was the mysteriously named “Transit Development Co.” which shared an address with the BRT on Montague St. (There’s a funny 1904 New York Times article titled ‘WANTED — AN EXPLANATION; Relations Between Transit Development Co. and B.R.T. Need Clearing Up” — apparently the BRT’s elevated-line holdings seemed just as Byzantine to contemporaries as they do 120 years later.)

You can see some good pics of the substation building and its notable arched windows in the 1940s tax photos – check block 85, lot 9 (two different shots), and another view in the lot 12 photo. This last pic actually features more of the substation than the lot 12 building itself. (The Municipal Archives couldn’t figure out the substation address but according to the Sanborn it would’ve been 38-42 Sands St.) The substation is a few doors to the west of the Love Nest Candy store at 50 Sands in your pics.

Today you can get a good view of the original back of the substation building, which now abuts Red Cross Place. It had arched windows in the back, too, bricked up today. (Incidentally, until just now I had always thought as you write, that Red Cross Place might be a small vestige of High Street west of Adams. But in fact that’s not right – Red Cross Place is a new street that would’ve been in the middle of old block 85. This stretch of High Street would’ve been right where today is the northern edge of the current OEM HQ building. This is actually quite obvious from a modern map, I just had never bothered to look closely.)

The substation is the only building on Sands Street besides the YMCA building to have survived the BQE, Cadman Plaza and Farragut Houses redevelopments.

To me, even better than this old, hidden-in-plain-sight building is the street outside. Just off the corner of Sands and Cadman Plaza East (former Washington St), where you mention a curious Sands St sign still stands, is a manhole cover in Cadman Pl E that reads “BHRR” – for Brooklyn Heights Railroad. You can easily see the cover’s BHRR initialism in streetview.

Jeremy Lechtzin – back in my early rainfanning days, I thought the electrical substation was the old Sands Street termination. LOL.

I noticed that the street signs in the 1940 photos are not the standard “humpback” design once so widely used in the city, but are of a much simpler design and are attached to the poles differently. Are these a remnant of an earlier design?

I think that was an alternate (cheaper) sign from the humps. No metal frame, etc.

Outside of nearly every Naval base in the country there was at least a couple of Naval Tailors catering to sailors.Unlike the

other 4 services sailors were very proud of their unique uniform and would spend money out of pocket for a set of

custom “blues” that they would often have decorated on the inside with colorful embroidery such as mermaids and

dragons.You can see an example of this in Steve McQueen’s Navy uniform in the movie”The Sand Pebbles”

Reliable and Franks were great.They had a large selection of such “Liberty Cuffs” for sale.Today servicemembers

no longer have any affection for their uniforms and stuff like the above would be considered corny and for”lifers”

You could also go to nycsubway.org for Brooklyn Transit els, which doesn’t require any account. From what I have seen there, Sands Street seemed to be a major hub until it was all torn down as the area was getting the subway. Speaking of the subway, High Street-Brooklyn Bridge is a remnant for the street’s original name for where Red Cross Place is now, though I’m surprised that the MTA never renamed that stop since then. Looking at that vintage pictures, I couldn’t believe how many blocks of downtown Brooklyn especially around Sands Street was lost to what we see there now. Then again, that’s the downside to urban renewal.

This just might be the most depressing photo essay you’ve ever posted, Kevin. A once-grizzled but vibrant streetscape transformed into a desolate, even poorer backwater of Moses-era “renewal.” Thanks for all the old images.

Before the China Mansion was the China Mansion, and after its YMCA days ended, it belonged to an Orthodox Jewish organization, perhaps a yeshiva? I remember as a child, riding past the building on the BQE, there were Hebrew letters right where the Chinese characters now appear. An interesting example of NYC demographic shifts!

Thanks for this, Kevin. My dad and his family lived at 125 Sands Street in the 40s. One spring day in the 90s, we took a trip to Brooklyn and he casually mentioned Sands St., which at the time I wasn’t aware that he had grown up there.

There was such disappointment in his eyes as we drove around the area. There was nothing left that he remembered from back then.

Regarding the uniforms, if one wanted one made with better material and with a better fit, then you had to go the tailored route at your own expense. I remember guys talking

about getting some gaberdines. On WestPac you could get tailor made ones much cheaper than in the USA. When I went on the Transit PD in the early 80’s we had to buy our

own Summer blouse, dress pants, and reefer coat. They recommended some tailors and I remember going to one in Brooklyn, maybe in this neighborhood. I got everything

except the reefer, not sure if I paid for it or if it was waiting for me to pick it up.

My wife’s family lived at 129 Sands…might you have a picture?

I was told that my Irish grandfather and his brother owned a pub on Sand St. If a Brit came in, they would serve him, but when he finished his drink they would brake the glass and throw it in the trash while he

was still sitting there. Erin go bragh!

hi – do you recall an establishment called the “shanghai house” on sands street and do you know what it was? please advise if you can- than you – charlie

My father (Joe Bianchi) and my grandfather (Harry Bianchi) owned Blue Star Cleaners at 181-183 Sands St., (shown above – 80-13 BK) during W.W II. I lived

with my family in a three-family house at 107 Prospect St. from Dec. 1938 until 1949 when our house was taken over by NYC to build the BKLYN. Queens Expressway. I shined shoes at the cleaning store and at the entrance to the York St. subway station toward the end of W.W.II I attended P.S. 7 elementary school on York St. I would like to hear from any one who lived in the area at this time.

Ron Bianchi