Time for another Longform Sunday, as I’ve been doing since Forgotten NY got started back in March 1999. This week, though, Sergey has supplied me with some more material, so I’m taking a second Sunday “off.” I’ve always been curious about the Brooklyn Navy Yard, but access has always been limited to outsiders; I’ve been on its outskirts, such as the new Wegman’s supermarket and the Russ & Daughters appetizing branch, but I’ve always been sheepish about approaching the various Checkpoint Charlies and actually trying to get into the place and walk around. I won’t consider it truly open to the public till all that is removed. After all, the Navy hasn’t been there since 1966!

In any case, Sergey recently spent some time in the Navy Yard…

By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

Since the founding of Forgotten-NY, Kevin Walsh has walked around the borders of Brooklyn Navy Yard, but hasn’t tried to get past the checkpoints as there are still plenty of “Government Property- No Trespassing” signs along its fences. The Navy decommissioned this base in 1966 and these days it’s a city-operated district of light industries that preserves most of the architecture from its shipbuilding heyday.

On a wintry day off from school, I wanted to take my children to BLDG 92, the museum of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Seeing the entrance closed on Flushing Avenue, I followed my navigation tool to the Clinton Avenue gate and told the security guard that I was visiting the museum. To my surprise, she waved me in and we entered the Navy Yard to explore its streets, buildings, and history.

At the entrance of BLDG 92, we admired the blend of postmodernism and brick exterior. We also noted the alleys of Brooklyn Navy Yard with their whimsical walkways, murals, and light fixtures. But the doors of BLDG 92 were closed. Coronavirus! My children were used to wearing their masks and maintaining distance at other museums that are open during the pandemic. But they did not cry as I prepared them for the possibility that this museum could be closed. So what’s a family to do?

My son was not in the mood for walking around on that windy day, so I couldn’t say much about the metal awnings reminiscent of the Meatpacking district, or the unique address system where every building has a number posted in a roundel affixed to the wall corner.

Kevin has admired every lamppost model in the city’s history since his youth, the way that Linneaus catalogued every animal that he could identify. So here’s a creation unique to the navy yard, where every lamppost is solar-powered. The street signs on this campus are oversized with the navy color and the property’s logo. Most cities in this country have a Market Street and Kevin has been to the one in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Brooklyn’s Market Street is inside the Navy Yard.

Market Street is near the Sands Street Gate, the most ornate entrance to the Navy Yard with its twin medieval-style turrets. At a certain point, a second floor was added here, eliminating the turrets and bridging the street. In 2010, the alteration was removed and the gatehouses were restored to their 1896 appearance. A couple of blocks north of this gate on Little Street is the historic Commandant’s House, the oldest structure at Brooklyn Navy Yard. You can walk around the Vinegar Hill neighborhood beyond this gate.

In the past year, Kevin documented the disappearing freight tracks in DUMBO and in Sunset Park. Brooklyn Navy Yard had its own railway system that functioned during its shipbuilding period. At TrainWeb, there are detailed maps of the tracks and historical photos. One of the system’s steam locomotives has been retired to a railroad museum near Rochester.

Building 121 is the former paymaster office for the navy yard, built in a romanesque revival style in 1899. At the turn of the millennium, this building manufactured Jewish burial shrouds. In 2012, Kings County Distillery opened its brewery here.

Building 20 stands out for its sloping roofline and brick circles unseen anywhere else in the city. How fortunate it is to be inside the Navy Yard, recognized for its history, in contrast to its stylistic relative, the late Lidgerwood Building in Red Hook. This former shipbuilding facility was redesigned in 2019 for Nanotronics, a science technology company.

Not all jobs at the 21st century navy yard are land-based. NYC Ferry has its office and docks here, where the boats are stationed when they’re not in use. In 2019, the commuter ferry service added a stop at Brooklyn Navy Yard’s Dock 72, a 675,000-square-foot office complex.

Most seaport cities have a Front Street that follows a downtown shoreline. Manhattan’s Front Street is now a block inland with South Street on the water’s edge. At the navy yard, Front Avenue has train tracks poking through the pavement. Looking east, one can see the office complexes of Dock 72 and Building 77.

If you’re fascinated by cranes on the waterfront, take a look at our previous essays on Domino Park in Williamsburg and IKEA Park in Red Hook. Those cranes haven’t picked up anything in decades, they’ve been preserved as industrial relics, but the ones at Brooklyn Navy Yard are still in use by GMD Enterprises, a ship repair business.

The biggest newcomer to the Brooklyn Navy Yard is Dock 72, which resembles a 16-story stack of shipping containers on a pier. It opened in 2019, eaturing murals by local artists, balconies with views of Manhattan, and spacious offices with high ceilings. The diagonal columns on its ground level resemble the cranes of the shipyard. This office complex is an early step in the navy yard’s transformation into a tech-manufacturing-office-cultural district, as seen in its 2018 master plan.

Akin to Chelsea Market in Manhattan, the million-square-foot Building 77 retained its industrial interior when new manufacturers, retailers and offices moved in. This one also has an alcoholic beverage producer, Transmitter Brewing. Built during World War Two, it was windowless for security. The transformed facility now has windows on all floors, retaining its rooftop antenna towers and concrete interior columns. Its neighbor, Building 3, has a 65,000-square-foot rooftop farm.

Steiner Studios is the largest enterprise at the Navy Yard, taking up 20 acres as the country’s largest film studio outside California. Since its opening in 2004, it has expanded its footprint and has plans to use the site of the former Brooklyn Naval Hospital at the navy yard. Some of the abandoned buildings of the former hospital will be restored and repurposed by Steiner.

Prior to World War Two, the eastern side of the navy yard was the site of Wallabout Market, a charming and crowded Dutch-revival collection of buildings that served as Brooklyn’s wholesale food market. Its architectural style and name were inspired by Wallabout Creek and Wallabout Bay, the bend in the East River where Walloon settlers established their farms in the early colonial period. The creek flowed past the market, with a retractile drawbridge carrying Washington Avenue across the creek.

The market had its own system of streets that are lost to history. In this 1924 De Salignac photo, we see the corner of Metz and Fleeman streets. Who were these namesakes? What was their connection to the market, if any at all?

The market’s location adjacent to the Navy Yard sealed its fate. With World War Two raging across the Atlantic, the federal government demanded tighter security and more space for the shipyard. The Wallabout market was condemned in favor of Brooklyn Terminal Market in Canarsie. On June 14, 1941, a ceremony marked the closing of Wallabout Market with a procession of the trucks to its new location.

Very quickly the old market was demolished, the section of Washington Avenue between Kent Avenue and Flushing Avenue was closed to the public, and the portion of Wallabout Creek upstream from the drawbridge was filled in. Further inland in Williamsburg, Wallabout Avenue follows the phantom course of this creek. The remaining portion of the creek has an abandoned train gantry. If such things interest you, there’s an active train gantry at Brooklyn Army Terminal, and preserved ones at Riverside South Park, and Gantry Plaza State Park.

The hospital operated until 1948, and then repurposed as offices until its abandonment in 1989. This campus inside the navy yard has a much-needed green space, the Naval Cemetery Landscape. Between 1831 to 1910, more than 2,000 people were buried here, mostly members of the armed forces. In 1926, the Navy relocated the dead to the Cypress Hills National Cemetery. An archeological study in the 1990s determined that hundreds of bodies remained buried beneath the grass. This inspired the construction of the wildflower meadow and elevated walkway. A honeybee colony feeds off the plants of this green space.

I exited the Brooklyn Navy Yard through the gate at Clymer Street and Kent Avenue. Unused shipping containers have been creatively repurposed here as a wall for Steiner Studios. In the background are apartment buildings designed for the hasidim of Williamsburg. Satmarchitecture where every balcony is under the open sky so that the Sukkot tents can stand under the stars.

As with my previous essays on neighborhoods, historic maps tell the story of the changing landscape. On the 1766 Bernard Ratzer map, we see Wallabout Bay as a sizable indentation on the Brooklyn side of the East River. I highlighted the roads crossing Wallabout Creek, including Washington Avenue.

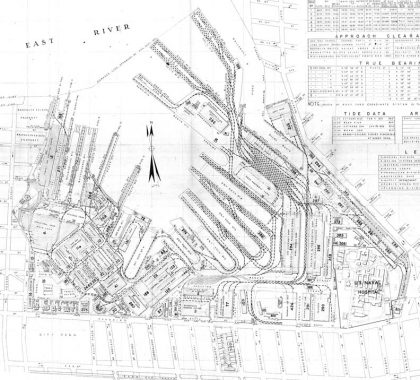

A 1943 map of the navy yard from Turnstile Tours, the official tour provider of Brooklyn Navy Yard, shows the present shoreline of the site with finger-like piers reaching into Wallabout Bay. I could write more about Wallabout Bay and its former artificial island, Cob Dock, but there’s a blog for such things. I can’t name every battleship built here from 1817 through 1965, but there is one that wasn’t which spent the last 37 years of its career at Brooklyn Navy Yard. In old postcards it looked like a floating building.

The USS Vermont was constructed in 1848 in Boston. Considered obsolete for combat as soon as it was completed, its career was spent as a storage and receiving ship, transporting goods and servicemen, never firing a shot. During the Civil War, it sheltered runaway slaves. Brooklyn Navy Yard served as its home for the last 37 years of its service. In this photo we see the Williamsburg Bridge under construction in the background. It was retired in 1901, sold and likely scrapped. I can imagine had this ship survived to our time it would have been repurposed as a floating restaurant or hotel.

If you wish to see more Brooklyn Navy Yard history on Forgotten-NY, see Kevin’s 2008 page on the yard’s historic buildings, and the condemned buildings of Admirals’ Row.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

2/7/21

8 comments

Fascinating.

Brooklyn had at least two additional Market Streets. One was Downtown; this was a short block extending from (old) Fulton Street to James Street; it appears to have been consumed by the Brooklyn Bridge approach. The other was in Cypress Hills/East New York, renamed in 1896 to Euclid Avenue.

I did a little bit of research into Fleeman and Metz Streets. It seems that their namesakes were Brooklyn politicians who were deeply involved with Wallabout Market.

William H. Fleeman was an independent Democrat who served as a member of the Kings County Board of Supervisors from the mid 1870s to the early 1880s when he was named City Treasurer by Mayor Seth Low. He went on to serve as Commissioner of City Works during the Low Administration, and in that job oversaw the construction and operation of Wallabout Market. Fleeman died in 1897, and when the market was expanded west of Washington Avenue that year, one of the new streets was named in his honor. Other streets included in the 1897 addition were four “fruit” streets; Lemon, Pear and Peach Streets, and Apple Avenue, along with an extension of Clinton Avenue. The “fruit” streets were in reference to the produce that went through the Market.

Herman August Metz served as New York City Comptroller 1906-09 during the Mayor George McClellan Administration, and would later serve a term in the U. S. House of Representatives. As City Comptroller Metz was responsible for leasing space at Wallabout Market. He had received complaints from merchants who did not wish to transact business on a street called “Lemon”, and applied to the Sinking Fund Commission to have the name changed. After teasing Metz over his proposal, the Commission authorized Metz to rename Lemon Street as he saw fit.

Thanks! you deserve a star!

The Navy closed the shipyard in 66 but still operated a reserve base there until the 1990s

Well done. Hope you were able to see one of the graving docks that can trace its heritage back to Thomas Jefferson (it would have been just behind you at Building 21)The “train gantries” are actually transfer bridges. these structures supported The bridges that allowed rail cars to roil from car floats (Barges) to the landslide tracks.

I now feel the need to use “Satmarchitecture” in conversation. Thanks, Sergey!

My paternal grandfather was a steamfitter at the Navy Yards from the 1910s onward through the second World War. The mixture of historic and current views is very much appreciated, as the combination helps provide a fuller sense of the evolution of the facilities.