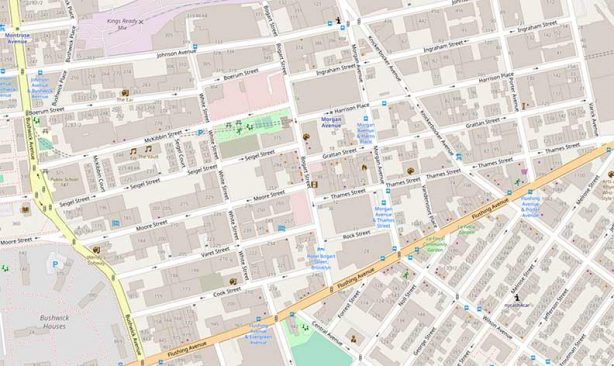

EARLY in October 2021 I decided to walk around a tight little enclave of streets located between Bushwick and Varick Avenues on the east and west and Johnson and Flushing Avenues on the north and south, in the area known as East Williamsburg for loack of a batter name. The region should have its own moniker, but within these bounds only a few streets such as Grattan have any longstanding residences, with the rest of the buildings given over to manufacturing and warehousing in the old days and thus it never really required a name. Many of these loft buildings are now being populated by residents now, so the area retains a fascinating mix of industrial and residential. Culturally this area seems to be what the western region of Williamsburg was in the 1990s, a recently industrial area now being populated by students and artists, who often serve as the canary in the gentrification coal mine; today, Williamsburg proper has turned into a ritzy region as a 2005 zoning change allowed large luxury towers to be built along the waterfront.

I have been here before, but perhaps discovered something I hadn’t noticed then.

Luxury waterfront towers aren’t in the cards for East Williamsburg unless the English Kills, out of this map excerpt on the north, ever attracts serious residential development and that area’s still heavily industrial, with Marjam, the building materials conglomerate, splayed along its western shore.

Geographically, Bogart Street separates two street systems, with streets coming in from western Williamsburg ending their runs at Bogart and streets totally contained within East Williamsburg beginning, such as Ingraham, Harrison Place, Grattan, Thames, and Rock. As for north and south streets, Knickerbocker Avenue was extended north to Morgan from Flushing Avenue early in the 20th Century; perhaps to support a streetcar right of way. Bogart Street is indeed named for the Dutch colonial immigrants whose later descendants included famed actor Humphrey Bogart. I’m not sure “Bogie” was aware of this.

Harrison has been about a “Place” since the 1890s at least, because there was already a Harrison Street in Brooklyn. Where is it? The question is, where was it. In Cobble Hill, Harrison Street was renamed Kane in the 1920s. However there is a Harrison Avenue, in western Williamsburg.

With your webmaster it’s always something and I made a mistake while importing photos from my camera into my computer and lost 20-25 of them, because I deleted them from my camera before I realized some didn’t make it into my machine. Thus about an hour’s work was lost. (This wouldn’t have happened over a century ago when I would have had to lug around heavy photographic plates to do this kind of work.) Fortunately Street View is my friend and I was able to get the best bits from my last hour of walking that way.

I enjoy taking the L train out to this realm, as its station mosaics are among the best found anywhere. The L, or the Canarsie BMT as it was known, was built between 14th Street in Manhattan and East New York in stages between 1924 and 1928 and was the last lengthy BMT line to see any major construction; in fact the new IND was already under construction in 1928. Knowing perhaps that the BMT-IRT mosaic tile sign plaques were going to not be a part of the new IRT, designer/architect Squire Vickers went “all out” and expanded the palate from the earth tones favored on previous BMT/IRT stations and the Canarsie Line got riotous color, with robin’s egg blue and pink added to the palette.

Montrose Avenue is interesting in its own right, and received the Forgotten NY treatment in 2015.

Street art is plentiful in East Williamsburg, here shown at the subway exit at Bushwick and Montrose.

The Topaz was a tapas bar (no, not a topless bar) at #251 Bushwick that replaced a bicycle repair shop. Its Yelp reviews go back to 2015, but it’s only present as a ghost sign now.

Another ghost bar, Barra Brava, is next door at #253 Bushwick. Its “bar” sign can still be seen as well as the rollgate artwork.

I turned onto Johnson Avenue, named for Jeremiah Johnson, an early 19th Century Brooklyn mayor, opponent of Brooklyn’s absorption into NYC (which was apparently under discussion as early as the 1830s and 1840s) and a Brooklyn historian. It forms the northern boundary of East Williamsburg as few streets run north of it as they are blocked by the LIRR Bushwick Branch, which serves freight exclusively.

There’s some colorful street art here, but notice the #236 Johnson Avenue Kendi Ironworks, in business since 1995. The identifying letters themselves are wrought iron.

The first of a number of concrete plants I encountered on this trip was Kings Ready Mix, on Johnson Avenue and Bushwick Place. Brooklyn is coterminous with Kings County, established in the 1670s; formerly, Kings County consisted of six separate towns that eventually coalesced into the City of Brooklyn before it joined NYC in 1898.

Bushwick Place, just east of Bushwick Avenue between Meserole and Boerum Streets, is actually an orphaned band in the road that, in the postcolonial era, became Bushwick Avenue. Here, we can see the brick tower belonging to the Hittleman Brewery.

The Hittleman Brewing complex is still more or less intact along Meserole Street and Bushwick Place. The building dates to about 1885 and was originally the Otto Huber brewery, one of Brooklyn’s largest, which at its peak turned out 10,000 bottles of beer per day. Huber had purchased the Hoerger brewery in 1866. Huber passed away in 1890 and in the 1920s, the Huber family sold to Hittleman, who operated the brewery until 1951. More recently, this building was where one of Williamsburg’s only remaining beer production plant and one of Brooklyn’s prime tourist attractions, the Brooklyn Brewery, was founded in 1988 before later moving operations to their present building on North 11th Street near Wythe Avenue. In the recent past the building has been used as a ginger ale bottling plant and currently hosts a gymnasium as well as a food wholesaler. More on this FNY page.

I liked the painted sign for Supreme Digital, a fine art digital printing and finishing studio at #3 Knickerbocker Avenue just south of where it meets Morgan and Johnson Avenues.

At Johnson and Porter Avenues I noticed a newly painted building sign for the Peter Jay Sharp Center in snappy black and white with the Copperplate font, an FNY favorite. It turns out that this is a homeless shelter, albeit one that has designs for being a cut above the usual:

The Porter Avenue shelter, called the Peter Jay Sharp Center for Opportunity, was built as the first step in replacing an 800-bed men’s shelter near Bellevue Hospital Center, currently the primary entrance point for single homeless men into the shelter system. That facility, in the original Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital, is an authentic piece of Gotham Gothic, with dark hallways smelling of industrial cleaners and bedrooms with rickety beds and ratty wool blankets.

Unlike the Bellevue shelter, the Porter Avenue shelter will be operated not by the city but by an independent nonprofit contractor, the Doe Fund. The Doe Fund runs a 150-bed shelter in Harlem, but that is only for homeless men who have decided to be part of Ready, Willing and Able, a work and lifestyle training program of the Doe Fund. The new shelter will have 100 beds for assessing the needs of men right off the street, 150 beds for men awaiting placement in programs elsewhere, and 100 beds in the Doe Fund’s work program. [NY Times, 12/7/03]

Across the street from the Jay Sharp Center are a pair of massive street vents that appear to be a variation on the Percheron (FRBL XL-5) model, as listed on FNY’s Street Vents page.

This massive rock on Varick Avenue north of Jefferson Avenue, according to Greater Astoria Historical Society director Bob Singleton, is more of a candidate to be the famed colonial-era “Arbitration Rock” placed at the border of Kings and Queens County than the one that is generally accepted to be the actual rock. Some historians believe the rock in the back yard of the Onderdonk House on Flushing and Onderdonk Avenues, seat of the Greater Ridgewood Historical Society, is the actual rock.

These nearly embedded tracks behind a chainlink fence at Varick and Johnson Avenues, as well as a few fenced-off rights-of-way, are all that remain of the Long Island Rail Road’s Evergreen Branch, which at its longest in the 1880s ran from the waterfront in Greenpoint to a connection with the LIRR Bay Ridge Line several miles to the southeast. Originally a passenger line, it survived as a freight conduit until the 1980s. When I began shooting photos for FNY in earnest in the late 1990s, there were several Evergreen trackways remaining as well as a few RR crossbuck signs.

The reliable RR historian Art Huneke has the full story.

Johnson Avenue east from Varick. You can see some Evergreen Branch tracks on the lower right. The building on the right was home to Goldberger Dolls, which produced the Eegee brand, from 1917 to 1980.

Factory building, Johnson and Stewart, formerly home to Englander Spring Bed Corp.

Caffe Vita, #576 Johnson between Stewart and Gardner, is described as a “Pacific Northwest chain serving house-roasted coffee in hip, relaxed surroundings.” That’s quite the snake they have there.

At Johnson and Gardner, street art is attaining a verisimilitude I thought exceeded capability with near-photographic quality. Are the artists tracing from actual photos? If so who are the people shown here? Comments section is open.

I’ll be honest. When I do Forgotten NY tours, which will resume when Covid subsides, I always wanted to wear one of those orange reflector jackets. Now I know where to get one.

I still have hundreds of vinyl recordings and a turntable to spin them on but I’ll be frank and tell you that I haven’t done so in years, what with my hundreds of thousands of MP3s I have collected on various drives. But vinyl still racks up big sales. The days of Sam Goody and Tower Records are gone but here, on the outskirts of the outskirts at #599 Johnson between Gardner and Scott, is the Brooklyn Record Exchange and I have to say, the selection looks interesting. On this page there’s a 12″ by Hugh Cornwell. Hugh who? The former Stranglers singer, that’s Hugh.

I detoured up Scott Avenue because I wanted to check out some things. Here at Randolph Street and Scott Avenue (yes, the corner is Randolph Scott) is a pair of metal Quonset huts, one housing the New Yorker Cheese Company, and the other, one of the area’s myriad auto repair shops. The Quonset hut by definition is a lightweight structure made of corrugated steel built with a semicircular cross section. It was developed during WWII at Quonset Point, in a naval construction area near Kings Point, Rhode Island; it is actually a variant of the Nissen Hut first used during World War I.

You may have thought only Vikings drank mead, which is wine produced by fermenting honey. But mead can be found in East Williamsburg, at the corner of Randolph Scott. In 2016 Enlightenment was NYC’s only “meadery” and I’m not sure if it still isn’t the only one.

To be honest, I had no idea the remote Scott Avenue footbridge over the LIRR freight-only Bushwick Branch had been recently replaced. I first spotted the older bridge it had replaced back in …. well, I don’t rightly remember the year; it could have been on bicycle forays to these realms back in the 1970s. I was aware of it when I got a series of photos beginning in 1999 that culminated in this FNY page describing it. That 1952 bridge was difficult to navigate because the stairs were steep and unforgiving. This new version somewhat addressed that flaw and it’s easier to ascend. The neighborhood youth have already gotten busy with their inevitable, vandalistic work. The walkway has been completely canopied, no doubt to make it difficult for neighborhood youth to throw objects on passing freights. The slots in the metal are enough to shoot a camera lens through…

…and thus obtaining views of the Bushwick Branch tracks are still possible. The line runs from Bushwick Place and Montrose Avenue in Bushwick, Brooklyn to its junction with the Long Island Rail Road Montauk Branch near Flusihng Avenue and Rust Street in Maspeth, Queens. At some points it’s smooth and well-maintained, but at others, it’s overgrown with weeds. It still sees a decent amount of freight trains.

From the Scott Avenue Bridge, the Shining City can be glimpsed.

I wandered up Randolph Street to take care of a little “housekeeping.” The single block of Seneca Avenue between Randolph Street and Flushing Avenue is the only part of Seneca that is at least partially in Brooklyn, as the undefended border of Brooklyn and Queens runs down the center of the street. The avenue (I’m not sure if it’s named for the Seneca Nation of Indians or Seneca The Younger, the Roman philosopher; it was renamed early in the 20th Century from Covert Avenue) is noncontinuous and its other sections are entirely in Queens.

This piece of Seneca is quite busy. Wholesalers Gotham Pipe Supply, Super Win Paper and Plastics Supplies, Aramsco restoration, remediation, environmental services…

…and I couldn’t not show you King Iron & Steel Works in this Building of 1000 Windows.

As Jen Psaki would say I “circled back” down Flushing Avenue. At #1160 Flushing, opposite Stewart Avenue I found this whopper of a ghost sign, raised metal lettering for Metropolitan Millwork, hidden by foliage during warm months.

Millwork is any type of woodwork or building product that is produced in a mill. This could include anything from doors, molding, trim, flooring, wall paneling, crown moldings, etc. However, millwork does not include flooring, ceilings or siding. [watchdogpm.com]

Next door on the left in this photo is another right of way for the Evergreen LIRR, now used as a driveway.

What do you see on Stewart Avenue? Some see garbage, barbed wire and a Peloton ad, but I see sloped walls that correspond to the old Evergreen LIRR right of way. Often when you see oddly shaped buildings, it’s a indicator of a former road or railroad.

Some of the rare residential buildings in East Williamsburg built as such can be found on Grattan Street, west of Varick. According to Benardo and Weiss’ Brooklyn By Name, Grattan was named for a 18th Century Irish Parliamentarian, Henry Grattan (1746-1820), who argued for Irish independence and the civil and political rights of Catholics. In the short run, he was unsuccessful, as the 1800 Act of Union merged the kingdoms of Ireland and Great Britain. The Irish Free State would not come into being until 1921.

In an interesting circumstance, the longtime tenant of this building at #117 Grattan at Porter Avenue, Venus Knitting Mills, retained that name long after the actual “knitting mill” moved out. The building was home to a company that mass produced knitted clothing, as were a number of others in the region.

An example of “two different residential building philosophies” as I call it, on Grattan between Porter and Knickerbocker; the late 18th-early 19th esthetic called for lots of (unnecessary but interesting) ornamentation like decorative brick and stonework, and the other 21st Century, flat and glassy, the glassier the better.

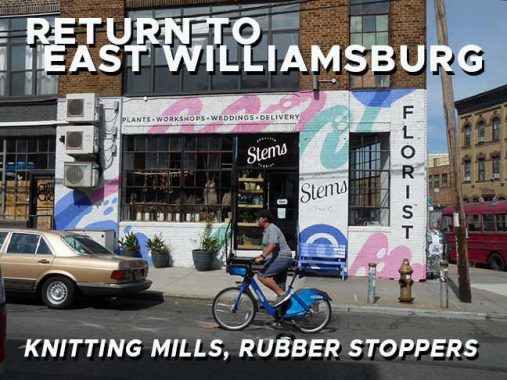

#92-96 Knickerbocker Avenue, NW corner of Thames, is another one of the area’s many massive brick, many-windowed buildings that was probably used for manufacturing as its original purpose but now is populated by many small businesses and perhaps some artists’ lofts, that include Knickerbocker BBQ Bar, Stems Florist and Standard Grooming.

When I was coming up, the trend was, grow your hair and beard as long as possible, and while some East Williamsburgians grow their beards as long as possible, many would never leave the loft without looking fastidiously styled, hence the plethora of “grooming studios,” i.e. barbers. (Me, I go down the street and she trims it into a manageable length every 6 weeks or so.)

Street art and just plain graffiti liven up another brick manufacturing building across Thames Street from the previous one.

The handsome PS 88, #48 Thames, used to hold down the corner of Vandervoort Place, but now there’s a one-story brick garage there at present.

Here’s where my cache of photos leaves off. I was far from finished walking though, and so will turn to Street View for the more interesting sights the rest of the way.

Engine 237, #43 Morgan Avenue just south of Grattan.

I’d do more FNY pages on northern Brooklyn firehouses, since no two seem to be the same and since most were built in the early part of the 20th Century, so they’re architecturally interesting. The Fire Department of New York has a website entry on all engines and H&Ls (here is Engine 237’s page), but seems to be resolute about not talking about the buildings or architects, preferring instead to concentrate on the important work conducted from them. However, the basics can be seen on those pages. Engine 37 was established in the Brooklyn Fire Department in 1895, became part of FDNY in 1898, and was renamed Engine 237 in 1913.

Especially in northern Brooklyn, many firehouses bear evidence of their former membership in the BFD. Engine 237 has this marvelous concrete trigraph with the most amazing letter “B” you’ll find anywhere. I challenge designers to run up a typeface based on these three letters.

The BFD was established in 1869 and continued until 1898, when Brooklyn became part of Greater New York and the BFD was absorbed into the FDNY.

This massive brick building at the west end of Grattan at Bogart has been “decorated” by the locals. At one time it was the factory Williamsburg Stopper Company which I presume produced the rubber stoppers that formerly held water in sinks and tubs.

I have no idea what’s behind the wall on the SE corner of Grattan and Bogart but what I do know is that there a pair of glorious wrought iron lampposts behind it, one of which is seen here. This style ws never used in NYC, so they must have been brought in from elsewhere.

Roberta’s, on Moore Street near Bogart, doesn’t look like much to write home to mother about from the exterior, but inside, there’s a gourmet pizzeria, outdoor picnic tables, and, surprisingly a radio station where I was interviewed by Mike Edison and Judy McGuire on their Arts & Seizures show on Sunday, July 17, 2011. Can so much time have passed since then? Sick transit, Gloria! Here’s my show.

I went down Moore to Bushwick, snapped the Bushwick Public Library and PS 147 (both pics lost) and inspected both Seigel and McKibbin Streets heading east. Here’s a lengthy, 3-story brick building, #221, built as a factory for Laitman & Laitman Traveling Bags. Presently, it is the Greenpoint Manufacturing and Design Center.

As a recipient of the Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit, 221 McKibbin Street has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The renovation and restoration plan for the building was approved by the New York State Historic Preservation Office and the National Parks Service. The historic rehabilitation process included a complete restoration of the building’s brick façade, the restoration and replication of the building’s steel windows, and the restoration of the original Columbia Products show room. [GMDC]

Seigel and McKibbin Courts appear to be slices of suburban tracts plopped unceremoniously into gritty East Williamsburg. They are semiprivate and have their own street signage and street lighting.

One of the two Morgan Avenue L train station’s entrance/exits, at Bogart Street. this is apparently the main entrance, but in spite of that, the MTA Bushwick map doesn’t even show a staircase here!

At #56 Bogart at Harrison Place is The Bogart or more precisely, The BogArt, a large artists’ workspace (no residential areas). Galleries within are open to the public.

The other end of the subway station, at Morgan Avenue, is in a thicket of concrete plants. I describe this fascinating yet desolate area on this FNY page.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

10/10/21