FORT Washington Avenue is one of the major north-south routes in Washington Heights, running from Broadway and West 159th to Fort Tryon Park at West 190th, running past NY Presbyterian Hospital, the uptown Port Authority Bus Terminal, and approach roads to the George Washington Bridge. Fort Washington Avenue, Washington Heights, the neighborhood, and the bridge itself were named for the Revolutionary-era fort constructed by the patriots but then captured by Hessian and British troops in November 1776. The fort was located in today’s Bennett Park at West 183rd, which is the highest point on Manhattan Island.

Some Sundays ago, I decided to walk its entire length, since I have never done that before. A few years ago, I was scanning and labeling postcards for the Greater Astoria Historical Society collection, a process that took me about 5 years (mind, I was only doing it 2 times a week at their HQ, three days at most) and I noticed something. Much of Washington Heights today looks pretty much like the postcards, which were produced between 1900-1920, at least on Broadway. Fort Washington Avenue is a bit different, but a good deal of it is unchanged for at least 80 years. Most of the differences have come from bridges and their approach ramps.

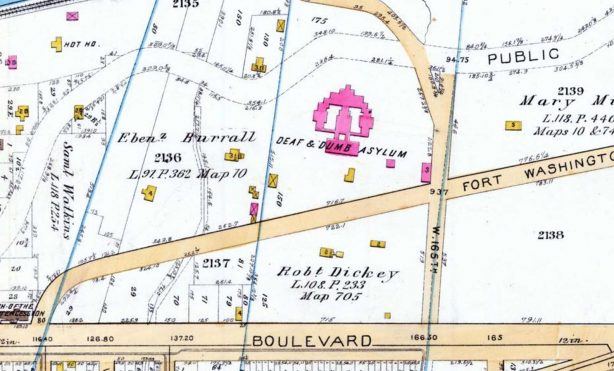

The southern end of Fort Washington Avenue can be seen on this map from 1895, with north on the right. (I checked an earlier map from 1867, and the avenue is missing there.) In 1895, it ran through open property. The “Deaf & Dumb Asylum” was located just south of West 165th, with today’s massive NY-Presbyterian Hospital north of that. The asylum, now known as the New York School for the Deaf, was founded in 1817 and acquired the Washington Heights property in 1853 from James Monroe (not the 5th President, but his nephew; the property was nicknamed “Fanwood” for his daughter Fanny). The school relocated to Westchester County in 1938, selling the Washington Heights property to Presbyterian. A large parking garage stands there now.

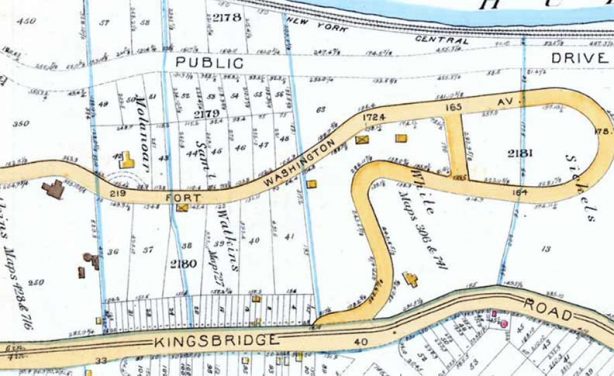

This is the northern end of Fort Washington Avenue in 1895, looping through what is now Fort Tryon Park. The traffic loop is still there, now known as Margaret Corbin Drive, with the Metropolitan Museum’s Cloisters now occupying the top of the loop. This is by far the hilliest part of Manhattan. In 1895, Broadway was still part of Kingsbridge Road.

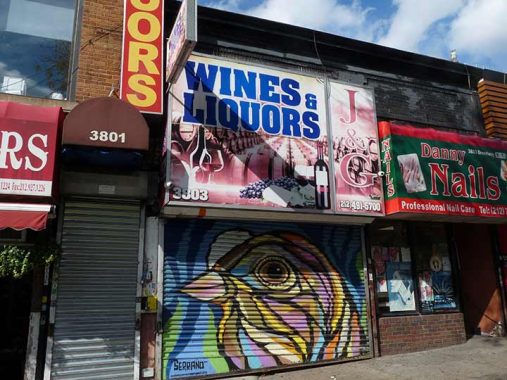

If you get off the #1 train at the 157th Street station and start walking around, you’re going to see a lot of painted birds. The 19th Century King of Birds, John James Audubon, lived in the area and is buried in Uptown trinity Cemetery.

A naturalist, ornithologist, and a painter who depicted birds so accurately that his works resemble photographs. Audubon lived and worked here beginning in 1841 when northern Manhattan was fields, forests, and streams. Jean-Jacques Audubon was born in what is now Haiti on his sea captain father’s sugar plantation, and grew up near Nantes, France, emigrating to the USA in 1803 to avoid serving in the Napoleanic Wars, becoming a citizen in 1812.

He had always expressed an interest in nature and the outdoors and especially in birds; in 1820 he traveled to the American South to begin his massive project of painting every native bird species in America. At first he could not find a publisher in the States, but his drawings became a sensation in Britain and Birds in America, today an unparalleled classic of its genre, gradually found release between 1827 and 1839.

The Audubon Mural Project is a public-art initiative of the National Audubon Society and Gitler &_____ Gallery that draws attention to birds threatened by climate change. It started in the Harlem and Washington Heights neighborhoods of northern Manhattan, where pioneering bird artist John James Audubon once lived and is buried; dozens of birds now perch on doors, walls, and security gates in a several-block radius. The project is informed by Audubon’s groundbreaking science report “Survival By Degrees,” which found that climate change will threaten 389 birds species—at least half of all North American birds—with extinction, and that no bird will escape the impacts of climate-change-related hazards like increased wildfire and sea-level rise. The project commissions artists to paint murals of these species, and it has been widely covered in the media, including The New York Times. [Audubon Mural Project]

Fort Washington Avenue proceeds north-northwest from Broadway and West 159th Street. Right off the bat, you can see some history. It’s hard to read the sign on the corner bar, but the sign says “Hilltop Park Alehouse.” It commemorates a former Major League Baseball park that stood in the region between Broadway, 165th Street, Fort Washington Avenue, and 168th Street from 1903 to 1912. The park was built in 6 weeks and sat just over 15,000 people. It was the home park of the New York Highlanders for most of its years of operation, and the New York Giants (the National League Giants) played in the park in 1911 while the Polo Grounds was rebuilt after a fire.

In what is called today the “dead ball era” when baseballs were manufactured differently and flyballs were tough to hit over fences, Hilltop Park was even more challenging as its initial dimensions were 540 feet to center and 400 feet to right! An inner fence was later added to give batters more opportunities for extra bases.

After the Highlanders left to play in the Polo Grounds in 1913 and changed their name to the New York Yankees, Hilltop Park was demolished. The Yankees rented the Polo Grounds from the Giants until 1923, making the 1921 and 1922 World Series the only ones two of the four played in one park, with the Giants defeating their tenants. The Yankees inaugurated Yankee Stadium with a World Series victory in 1923 (just as they would the New Yankee Stadium in 2009).

Note: the St. Louis Cardinals beat the St. Louis Browns played the Series in Sportsman’s Park, St. Louis, in 1944, and the Los Angeles Dodgers beat the Tampa Bay Rays at Globe Life Stadium in Arlington, Texas in 2020.

One question that perplexes me is, when was the “dead ball” changed? It wasn’t an immediate reaction to Babe Ruth, whose raw power sent baseballs over fences while he was still pitching with the Red Sox. Even after he joined the Yankees he continued to out-homer many major league teams for several years.

Fort Washington Avenue is on a curve between Broadway and West 160th Streets. In an unusual situation, two apartment buildings on the west side of the street are actually built perpendicular to the other. Named the Rio Vista and the Rio Grande, possibly because the upper floors have views of the Hudson.

The only other situation like this in Manhattan I can think of is on Commerce Street in Greenwich Village, which is shaped like an “L.”

As I have mentioned much of Washington Heights still looks as it did decades ago. Many of the apartment buildings have a similar design with brickwork below and intricate stonework on the upper floors. This stuff tends to weaken and break off after several decades, thus, many are scaffolded while repairs are effected. This is likely a factor — besides cost — why most buildings have plain or even glass fronts. If they had a vote, the birds that Audubon painted would have a problem with glass fronts.

We have seen that this part of town has long been associated with institutions dealing with afflictions, from the NY School for the Deaf mentioned above. Nearby in the same era was the Institution for the Blind. Today, the massive complex of New York-Presbyterian Hospital occupies the area from West 165th to West 168th from Riverside Drive to Broadway, with Fort Washington Avenue running up the center.

NY-Presbyterian had its origins in 1771 as New York Hospital and chartered by King George III, with Presbyterian Hospital founded in 1868 by James Lenox, the philanthropist for whom 6th Avenue above Central Park was named. Presbyterian and Columbia University affiliated in 1920 with the combined institutions building the current complex beginning in 1928. The New York and Presbyterian Hospitals association is relatively recent, going back only to 1998.

Though I almost always never get to use them because they’re on private property I like building-to-building skywalks, whether older ornate ones like the Gimbels Skywalk on West 32nd or the more modern ones. The one at NY-Presbyterian irks me, though. You build a skywalk to let people look up and down the avenue and then… put a large ad on it.so no one using the bridge can see out of much of it. Jeez.

This photo leaves out a much higher skywalk on the top floor.

This was the first curbside electric vehicle charger I have seen in NYC. I have seen one or two since. As electric-powered vehicles become more common you will likely see more. I favor the proliferation of electric-powered vehicles, as it blunts the attack of people who want to eliminate fossil fuel-powered vehicles: however, their objections are more philosophical than practical, so you won’t get rid of such objectors anytime soon.

The 22nd Regiment Armory was built in 1911 and was one of the prominent structures in the area then, along with the health institutions and Hilltop Park. Unfortunately the exterior has had sidewalk scaffolds since 2017 (!) so here’s a Street View from 2014. The 22nd has long been merged and disbanded with other National Guard units so today the building is called simply the Fort Washington Avenue Armory. It is famed today for its large running track on the third floor, the home of the National Track and Field Hall of Fame, and the site of the annual winter Millrose Games.

When I first saw Haven Avenue on the Manhattan map many years ago, I thought it because of the “haven” offered by NY-Presbyterian and possibly the other health institutions in the region. Instead it is named for John Haven, who purchased land in the area in 1834 and whose family owned it until 1895. Formerly continuous to West 181st, where the Haven farmhouse was located, the avenue now runs continuously from West 169th to 177th, with the remained either eliminated when the George Washington Bridge and its ramps were built beginning in 1930. The short section near 181st is an offramp of the Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Drive, which entwine like lovers in the Bridge area.

Haven Plaza is the pedestrian-only walkway between Broadway and west 169th. Joe Hintersteiner (1949-1995), meanwhile was a popular educator and artist in the Washington Heights area.

Wright Park

Speaking of former property owners, here’s a park I had no idea existed and had never been in before this walk. (I always say that if a week goes by and I’m not in a part of NYC where I’ve never been, I’m doing it wrong.) J. Wright Hood Park, between Haven and Ft. Washington Avenues and West 173rd and a bit short of West 176th, was named for a wealthy banker and financier from Philadelphia who made large anonymous contributions to what is now the Washington Heights Branch of the New York Public Library. His mansion was located nearby.

The park consists of a large play area for the kiddies, with a replica of the GWB, and grassy knolls in the back where you can see the real bridge. It was established in 1925 and also has handball and basketball courts.

There’s more: an elevated plaza on the park’s west end above Haven Avenue with a prime view of the Bridge. Unfortunately, my images were dimmed by a cloudbank that arrived just as I was shooting here.

I was puzzled by a very tall thin shaft of metal in the plaza, thinking it to be a cell phone relay tower of some kind. No, it’s Art. It was installed in 1974 by Terry Fugate-Wilcox using bolted magnesium and aluminum and titled 3000 A.D. Diffusion Piece, as that is the time period when the magnesium and aluminum will diffuse or amalgamate. Modern thinking, though, is that the area will be mostly under water by the 31st Century.

The park also hosts one of the Independent Subway (IND)’s “nonstandard” stations. This particular station was built in 1932 and the Manhattan-bound entrance is incorporated into the park’s exterior stone wall. The IND is usually thought of as being very mass-produced and rote as far as decor goes but as we’ll see there are occasional surprises: after all, Squire Vickers, who designed the busier late IRT and BMT stations, was still in charge of subway design at this point. (I’m not sure what came first, the park’s stone wall or the IND’s stone entrance; one may have imitated the other.)

This Moderne building across the street from the subway likely dates to 1932 or thereabouts, as well.

I haven’t spent a great deal of time in NYC’s Port Authority bus terminals. All to the good, I suppose. I think I was last in the GWB bus terminal on one of the late Bernard Ente’s “hot dog walks” to two locales in Fort Lee and that was back in the early to mid-2000s. I was last on the 42nd Street counterpart in 2015 at 6 AM, meeting Lisa J., a friend from out of town. I remember a job interview in Hackensack in the 2000s. That’s it for relatively recently. When I was a kid we’d take summer vacations in the Troy, NY area and we’d get a bus from the Port Authority, and there were rides to Palisades Park on the Orange and Black line, remember those?

There must be something in the contracts that bus terminals, like parking garages, have to be ugly so that people will not be eager to spend much time in them. I don’t think that was on the mind of Italian architect Pier Luigi Nervi when he designed the GWB terminal constructed in 1963. The midtown bus terminal is supposed to be completely overhauled within the next decade. But the intrinsic problem is that the people who use it don’t keep it clean and neither do its managers. Wealthier people travel by car or plane, and time and experience have proven that if you don’t have pride of place, whatever place that is will eventually be junked.

The overpass does have some interesting Holophane “buckets” that have LED bulbs but have kept their diffuser bowls; I wish most modern LED would do the same.

Going Holyrood: The Gothic Episcopalian Holyrood Church, Fort Washington Avenue, and West 179th, was built between 1911 and 1914. The congregation itself dates to 1893. The name means “Holy Cross.” The building is shared with the Spanish speaking Iglesia Santa Cruz.

I liked the entrance lamp stanchions on this Ft Washington Avenue building just south of West 181st.

Fort Washington Collegiate Church, built in 1909 at Ft. Washington Avenue and West 181st, is a descendant of the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church. It was constructed on the former property of James Gordon Bennett, publisher of the New York Herald (cf. nearby Bennett Avenue).

181st Street is a fascinating mix of cultures and cuisines. This market takes its name from the 1984 Robin Williams vehicle written/directed by Paul Mazursky about a defector from the Soviet Union.

I do not know who has been posting these pamphlets showing historic images of Washington Heights on Fort Washington Avenue, but whoever it is…bravo! They are protected from elements and vandals by plastic and who can tell, some of the more curious residents will see what their neighborhood looked like decades ago and learn a little history.

I know it’s the home of the highest hill in Manhattan and has a nifty plaque showing Fort Washington’s original location but I was underwhelmed by Bennett Park, between Ft. Washington and Pinehurst Avenues and West 183rd and 185th Streets. I found it somewhat blah compared to Wright Park a few blocks south. It was named for James Gordon Bennett Senior, a Scottish immigrant who founded the New York Herald in 1835 and purchased land in northern Manhattan in 1871. Bennett Avenue is also named for him, and he has a plot in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. The Herald merged with the New York Tribune, founded by his staunchest rival Horace Greeley, in 1924 and the paper continued on until 1967.

Another unusual subway entrance at the north end of the West 181st Street station can be found here, bearing the earmarks of its 1932 construction date. To my knowledge this is the only NYC subway station that uses wood entrance doors. Another similar entrance can be found at Overlook Terrace and West 184th, amid a thicket of Manhattan schist outcroppings, also with wood doors.

Note the stenciled lettering above the standard black and white metal sign.

A pair of buildings serving the Jewish faith can be seen along Bennett Park. Their stone facades look similar but the buildings are about 25-30 years apart in age. The Fort Tryon Jewish Center was founded in 1938 and built this edifice that is a match for the subway entrance adjoining it in 1950. Meanwhile, the Hebrew Tabernacle was founded in 1906 and moved to this building constructed in 1931-32 for the Fourth Church of Christ, Scientist, in 1973.

For a contrast I decided to hit Pinehurst Avenue for a block. Good thing I did since I found the unusually-named Pandering Pig near West 187th. I immediately assumed with was a gut bucket dive but nothing could be further than the truth, as the menu is something on the haute side, though admittedly I’m used to diners. I’d bring a date in here.

Paterno Castle stood at what is now Cabrini Boulevard and West 181st Street in Washington Heights. Italian immigrant Dr. Charles Paterno (1877-1946; no relation, as far as I know, to deceased Penn State coach Joe Paterno) built it between 1907 and 1909. It contained a mushroom cellar, a swimming pool surrounded by birdcages, and a 20′ by 80′ master bedroom. Its seven-acre site was surrounded by woods and greenhouses.

Charles Paterno and brother Joseph built many of the grand apartment buildings in the area, and by 1918 he owned 75 buildings housing about 28,000 people. In that year he built 270 Park Avenue, which takes up the entire Park-Madison-47th-48th Street block, which stood until 1960. By 1938, Paterno had demolished Paterno Castle and built Castle Village, five thirteen-story towers containing 580 apartments. But the old Castle’s retaining wall can still be seen along Henry Hudson Parkway.

“Trivium” is a compound Latin word meaning “three roads.” Cabrini Boulevard, Pinehurst Avenue, and West 187th Street meet here, opposite Castle Village at what the Parks Department has named Paterno Trivium.

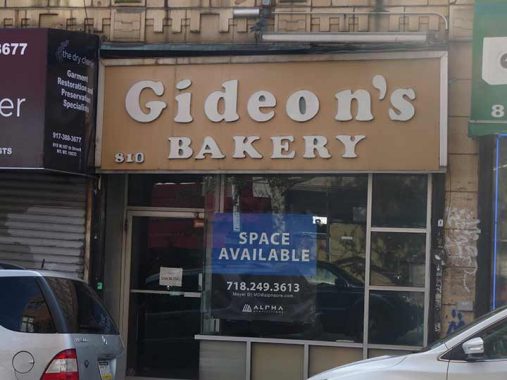

I haven’t hung around bakeries except for holiday gifts; I dearly wish I could eat more cookies, pies, cakes etc but high normal blood sugar and cholesterol keep me away. Thus, I notice the sidewalk signs. The closing of Gideon’s Bakery on West 187th and its sign with Cooper Black letters in 2016 wasn’t lamented in the press quite like Glaser’s closure was in 2018. Nevertheless it was noted as the last kosher bakery in Washington Heights. Both had super-basic signage, the kind I like.

To me it’s incredible this space hasn’t been leased in 5 years, but the owner is likely charging astronomical rates and wants a franchise.

I keep saying I’m going to photograph every NYC step street. They are found in every borough, with the most in Manhattan and the Bronx, the fewest in Queens (where I have only seen one!) I also keep saying I want to photograph every platform lamp specimen on NYC subway elevateds. I doubt I can complete either. West 187th between Fort Washington Avenue and Overlook Terrace is particularly steep. The “Patriot” artwork commemorating the Prison ship Revolutionary War martyrs seems to have vanished, or I can’t see it from here. I did not want to clamber down to see if it is mid-step flight.

To me #689 Fort Washington Avenue did not look like it was always an apartment building. I was right. St. Elizabeth’s Hospital opened at 225 West 31st Street in 1870, moved to 415 West 51st Street by 1905, and moved to its last location here in November 1927, closed in 1981, and was renovated as co-op apartments.

It wasn’t named Overlook Terrace for nothing as it’s built on a high scarp “overlooking” Washington Heights and the Bronx as well as what appears to be an abandoned swimming pool. At West 190th, we see a building that has what I call the “Bronx curve” as many corners in the borough do not meet at a 90-degree angle and architects gave buildings sweeping curves to engineer better views.

Northern Avenue’s renaming decades ago as Cabrini Boulevard is hardly arbitrary. Frances X. “Mother” Cabrini has been associated with Washington Heights since 1890, when she purchased a parcel of property above West 190th Street; a school was established there soon after. In 1933, her remains were moved from her burial place in West Park to the chapel of Cabrini High School as part of the process of making this a national shrine to the saint’s memory. A new Shrine was constructed in 1957, and her remains can be seen in a glass case beneath the chapel altar: a wax replica of her body contains the saint’s bones.

These full size stanchions used to be a lot more common for the IRT, BMT and IND but this seems to be the only one remaining in the city. I’m surprised the MTA hasn’t removed it because of their nonending quest for station ID uniformity. Today there’s an illuminated green globe indicating the entrance is open 24/7, but formerly there were incandescent bulbs lighting up the cutout “SUBWAY.” It’s just waiting for a delivery truck to make quick work of it, but it’s made it now for nearly 90 years.

Today one of the bulbs was lit up! I check on this post at least twice a year.

Nearby stands a couple of freestanding IND lamp stanchions also from when the station opened in 1932. this is the only station in the subway system that sports these. They give an intriguing look at what IND elevated stations’ platform lighting may have resembled, if the IND Second system, which included some elevated stations, had ever been built. To me they definitely look weird, with cowls that make them look like Martians. Some of them still have greenish-white mercury bulbs. They are well-protected by fencing.

Here Fort Washington Avenue ends and Margaret Corbin Drive begins at the south end of Fort Tryon Park, named for a woman who “manned” a cannon after her husband was shot during a battle in the war for independence. I clambered around Fort Tryon Park — one of the few places in NYC commemorating a Loyalist — and got plenty of pix, but will need to do more research to get a handle on the place; I did a preliminary post some years ago. I was planning an exterior tour here in 2020 before a certain virus changed the world.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

11/21/21

17 comments

Here’s an answer to the baseball question, plus some additional stuff:

(1) The dead-ball baseball era ended with the 1920 season, as described in the Wikipedia article that can be read via this link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Live-ball_era The changeover was due to a number of factors, not just Babe Ruth’s hitting prowess (he hit 54 home runs in 1920). Another reason was to prevent future batter deaths because of the previous practice of keeping a game ball in play for an entire game (hard to believe). Such practice led to the death of the Cleveland Indian shortstop Ray Chapman in a game against the Yankees at the Polo Grounds on August 16, 1920.

(2) A third World Series was played in one stadium in 1944, when the St. Louis Cardinals defeated their hometown rivals, the Browns. Both teams shared Sportsman’s Park, long since razed. The Cardinals had better teams from the 1920s onward; the Browns were perennial doormats. Since the Browns owned the park, the Cardinals were the tenants; the Browns won the 1944 American League pennant because of the dearth of many baseball stars because of World War II, when many served in the military services. Eventually the Browns could not survive financially and became the Baltimore Orioles in 1954, selling Sportsman’s Park to the Cardinals in the process. The park was renamed Busch Stadium in deference to its new owners, the Anheuser-Busch brewery, and was closed and razed in 1966.

(3) The GW Bridge Bus Station (official name) in 1963 replaced a series of small, street-level commuter bus terminals at 166th-167th Streets and Broadway, opposite the Medical Center complex. Commuter buses to/from Bergen County NJ and Rockland County NY also stopped at 177th St. and Fort Washington Avenue to permit easy transfer to and from the A train at 175th St. Station.

I’m curious … Where is the only Step Street in Queens that you have seen?

Two, now that I think of it, 53rd Avenue between 65th Place and 64th Street and 48th Ave at 59th St.

How about 125th St. between 5th Ave. and Lax Ave. in College Point?

When I went to school in Manhattan, took the #21 bus on the Red and Tan Lines to Bergen County, The terminal, with Tan brick and Red trim on the East Side of Broadway at 166th was at the top of the subway stairs and included a Cushman’s Bakery, Always brought goodies home.

Fort Washington Avenue was already laid out and mapped and was known as Fort Washington Ridge Road. Plates 31 and 32 of the 1879 G.W. Bromley Atlas of the entire city of New York. It followed the exact same route as it does today, from Eleventh Avenue (Boulevard) and West 160th Street and ending at St. Nicholas Avenue (also called Kingsbridge Road on these plates) and West 198th Street.

The “Dead ball Era” ended after the 1920 season during which shortstop Ray Chapman of the Cleveland Indians was killed by a submarine pitch from Carl Mays in the 5th inning of a twilight game against the New York Yankees. This was the only death which ever occurred during a MLB game. Rather than change the construction of the balls, which remained consistent between the transition from the “dead-” to “live-ball eras”,[1] rule changes were instituted around how the balls were treated. Starting in 1920, balls were replaced at the first sign of wear, resulting in a ball that was much brighter and easier for a hitter to see. Additionally, pitchers were no longer allowed to deface, scuff, or apply foreign substances to the ball.

Thank you for this entry! A couple of small additions: J. Hood Wright Park was featured prominently in a portion of the movie “In The Heights,” and was the setting for a love song and dance. I hope you have seen or soon see the film! Also, I should mention that the 190 St. station for the A train also has wooden doors, both on the upper entrance at Ft. Washington Ave. and the lower entrance at Bennet Ave. Good work, I love reading this site!

Would 32nd Street between Astoria Blvd. North and 24th Avenue qualify as a step street?

It should, technically, but it’s not very impressive as step streets go.

One thing that Audubon could not have predicted is that the famous ivory-billed woodpecker would end up extinct thanks to Singer sewing machines. By the 1930’s habitat loss had greatly reduced the large showy birds’ population over almost all of its former range in the south. Its last stable population was in a 125 square mile Louisiana forest known as the Singer Tract, the company having bought it many years earlier as a source of wood for sewing machine cabinets. So long as the Singer Tract remained undisturbed the bird was in no danger of extinction.

Unfortunately, in the late 1930’s Singer decided it really didn’t need all that much land and sold off the logging rights to the Singer Tract. The National Audubon Society pleaded with the company to reconsider, to no avail, and as there were no endangered species laws at the time nothing could stop the logging. The last confirmed sighting of an ivory-billed woodpecker was in 1944, and after decades of careful searches turned up nothing the federal Fish and Wildlife Service just recently declared the species officially extinct.

Thanks for nothing, Singer.

I’m not sure this counts, but due to the pandemic, the 2020 world series was also played in one park – Globe Life Field, In Arlington, TX. The LA Dodgers beat the Tampa Bay Rays in 6 games.

How soon I forgot

A few blocks east of Fort Washington Avenue, Audubon’s namesake avenue runs north-south between 165th and 193rd Streets. Years ago, when telephone numbers had alpha-numeric exchanges, AUdubon 3 was an Manhattan phone exchange – in Harlem, Washington Heights, and Inwood.

Those Kosher bakeries make the best rye bread,the ones that have the union stamp

pasted on the side of the loaf.I could eat slice after slice just plain with nothing on it.

Doug Douglas mentioned Cushman’s bakery. I lived at 49 W. 135th Street – the current site of Harlem Hospital. I remember Cushman’s very well, especially the aroma once you walked inside. I am always reminded of that same aroma when I walk into Lord’s bakery at Nostrand & Flatbush Avenues in Brooklyn. Ahh, memories.

Oops. I forgot to mention that Cushmans was located on the SE corner of 135th & Lenox – just a few steps from 49 W. 135th Street.

Thanks for the bit about Haven Ave! (John Haven is my ancestor). Loved your entire post, and your project to preserve/recapture the fascinating history of Gotham. Please keep it up!