QUEENS Village, centered at Springfield Blvd. and Jamaica Avenue, was known originally as Little Plains, then Brushville, after a local landowner, until about 1920. The present elevated station was constructed in 1924. Interestingly you can still see the remnants of a layup track here. In 1856, residents voted to change the name of the town to simply “Queens” and that name persisted until at least the 1920s, when the Long Island Rail Road added the word “Village” to the station name. Before the 1898 consolidation the village of Queens was located in the county of Queens, which may have led to some confusion. However, people have seemingly adjusted to saying “New York, New York” for over two centuries.

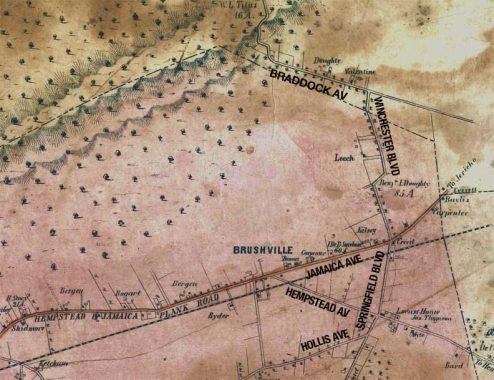

The wavy lines at the top of this Dripps map made in 1852 depict the glacial moraine that bisects Brooklyn and Queens from east to west and forms a line of high hills. The Cemetery Belt, consisting of 17 separate graveyards along the Brooklyn-Queens line further west in Cypress Hills, was just starting to form at about this time. Today, the Grand Central Parkway runs along the moraine, which marks the southernmost limit that a glacier pushed south during the last Ice Age several thousand years ago.

Only a few roads were built through these high hills. One of them was called Rocky Hill Road. I’ve done a FNY feature on this ancient road, which is still in place today, consisting of parts of 46th Avenue, Bell Boulevard, Springfield Boulevard and Braddock Avenue; only a short two-block stretch in Auburndale retains the old name.

The Creedmoor Rifle Range was later built on the lands north of Rocky Hill Road/Braddock Avenue. Today’s Creedmoor Psychiatric Hospital was later built on its grounds.

The west of the map was a flat, swampy plain in 1852 with only a few scattered dwellings and no roads traversing it. However, several roads still in use today can be found near the bottom of the map: Hollis Avenue, then known as Old Country Road before Frederick W. Dunton, a native of Hollis, New Hampshire, began to develop the area in the 1890s. Hempstead Avenue branches off from Jamaica Avenue as it did then, only today it is called Hempstead Turnpike in Nassau County, part of NYS Route 24.

The major plank road through the region was the Hempstead and Jamaica Plank Road. As the name implies it took horses, carts and stagecoaches to and from the town of Hempstead, then in Queens, but after 1899, Nassau County. It evolved into Fulton Street in the town of Jamaica and the Jericho Turnpike east of that. The whole stretch in Queens was renamed Jamaica Avenue around 1920, and the section in Queens east of Cross Island Parkway was renamed Jericho Turnpike in 2005, matching the Nassau County name the road is known as. The entire stretch is also now NYS Route 25.

Springfield Road ran through the Queens town called Springfield; the name survives in the boulevard and the Springfield Gardens neighborhood. The road was later extended north through the hills, assuming part of the old Rocky Hill Road route, and today ends at Northern Boulevard in Bayside.

I have previously posted a more recent trip I made to Queens Village in 2020. However, looking through the backlog, I have some photos from 2017 I haven’t yet used (to my best knowledge), so I’ll present here. I have over 120 images, so I’ll split it into two entries.

I began this trip at Jamaica Avenue and Springfield Boulevard, where the Queens Reformed Church (Eglise de Bethesda) dominates the NE corner of Jamaica Avenue and Springfield Boulevard. The “old white church” opened in 1859 as the Reformed Protestant Dutch Church. The columned portico was added in 1947. The coat of arms, which can be seen in the sanctuary, features two foreign-language phrases: Nisi Dominus Frusta (Latin, ‘Without the Lord all is in vain”) and Eendracht, Maakt, Macht (Dutch, “Union Makes Strength”).

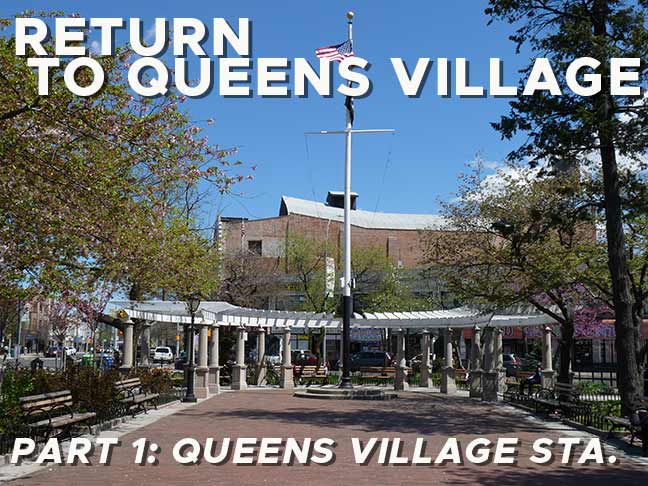

Something that Queens and Staten Island do, and I wish the other three boroughs would, is place identifying signboards in the center of their neighborhoods. Of course neighborhoods used to be small towns, and Queens and Staten Island still maintain traces of those days of small villages and towns connected by roads and railroads.

The Queens Village signboard is especially handsome, with lettering in the classic fonts Goudy Bold and Zapf Chancery.

The intersection of Jamaica and Springfield is marked by a public park, Queens Village and Bellerose World War II Veterans Memorial Plaza. The plaza contains a handsome colonnade and a memorial to area Queens Villagers killed in WWII, Korea and Vietnam. The memorial stone was dedicated in 1949 but oddly, NYC Parks does not identify the sculptor.

Parks is now phasing out the brown park signs with the generic leaf and gold leaf Palatino font; I’ll miss them.

There has been a railroad station on the site of today’s Queens Village station since the beginnings of the LIRR in 1837, when trains of the Brooklyn and Jamaica Railroad, later acquired by the LIRR, made occasional stops here. Regular service began in 1879 as the region began to be more greatly settled and these tracks became part of the LIRR main line. The present Spanish Colonial station was built and the tracks placed on an embankment from 1923 to 1924 (as was my familiar local Bayside station, as the railroad was striving to eliminate grade crossings at least within the five boroughs). The station was renovated from top to bottom in 2013 with new elevators and station lighting. I happened upon it on a weekday and that was fortuitous as the waiting room on the Manhattan-bound side is open from 5 AM to 2 PM, and I was able to scuttle around inside.

Most trains bypass the station, which has hourly stops, most heading east to Hempstead or west to Penn Station or changing at Jamaica for Brooklyn or Grand Central.

The LIRR has been slow to adopt LED lighting on its platforms (for example, my station at Little Neck still has sodium lamps, which I think do the trick just as well) but these new lamps came with the 2013 renovation and are now a decade old.

The Queens Village station has always had this curious single track behind the eastbound platform. It may have always been used to layup work trains or it may have been used for freight. (Again, at Little Neck, the station parking lot stands on what was once a third track spur).

If you look carefully at the tower, just east of the station, you see the single word “Queens.” The tower name is a relic of when Queens Village was simply known as “Queens.” As stated earlier, “Village” was likely tacked on when western Queens became a NYC borough in 1898.

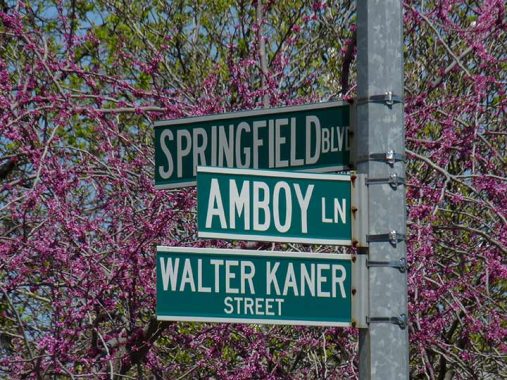

Amboy Lane is a dogleg connecting Jamaica Avenue and Springfield Boulevard around Veterans Plaza, mainly used for auto shortcuts and bus terminals. If you read the NY Daily News in the 1970s and 1980s, you know Walter Kaner (1920-2005), who also wrote a showbiz column for the Long Island Press and Western Queens Gazette. His career began during World War II as he made radio broadcasts as “Tokyo Mose” to counter the anti-American propaganda of the erstwhile Tokyo Rose (a group of female propagandists, not one single broadcaster). In the 1950s, he would occasionally sub for Ed Sullivan (who was also a showbiz columnist by trade) on his Sunday night variety show.

This view on Springfield Boulevard shows the rear of the long-shuttered Queens Theater. The theatre, designed by architect Thomas Rau, opened December 29, 1927 and while it was originally a vaudeville theater featuring stage shows, it converted to films early on. Almost to the end of its run, though, the Queens was unable to show first-run pictures, which were available in Jamaica, anyway, and switched to porn before it closed. In 1938, two of the projectionists, Nathan Klein and Solomon Schulman, got into a fight; Klein was killed, and Schulman was convicted of manslaughter and received a 15-year sentence. The theatre eventually became the New York Deliverance Gospel Church, but it’s now shuttered and awaiting the next chapter.

FDNY Engine 302, Hook & Ladder 162, 218-44 97th Avenue off Springfield Boulevard. Engine 304 was organized in 1923. Ladder 162 in 1928. The firehouse was constructed in 1927 during the Jimmy Walker administration and is typical of firehouses constructed between 1925-1935.

South of the railroad Springfield Boulevard gains a couple of lanes and becomes an important local route bringing traffic south to the Belt Parkway. It is one of the oldest roads in the area and predates the map from 1852 shown above.

This relatively unadorned private house at the corner of Springfield Blvd. and 100th Avenue, like many of its compatriots along the boulevard, was once much fancier. Most of its exterior decorations, as well as its porch, have been stripped off as witness this photo of the building in the 1960s from the Greater Astoria Historical Society photo archive.

Another house along this stretch of Springfield Boulevard that has had aluminum siding added, but has kept more of its old architectural elements.

Nassau County residents know all about Hempstead Turnpike, one of its main east-west auto routes, synonymous with NY 24 for its entire length from the Queens line to East Farmingdale. Some of Nassau County’s chief attractions are arrayed along its length, from Belmont Park to Hofstra University to the Islanders’ former home, the Nassau Coliseum, to RXR Plaza, where I work (as of 2023) for publisher Marquis Who’s Who (but I work from home and have never traveled to headquarters, at least not yet!)

There is some dispute over where the name Hempstead comes from; like Gravesend, some say it’s Dutch in origin, some English. When the region was settled by Europeans in the 1640s, proponents of the Dutch origin say the name comes from the town of Heemstede in Holland; while English boosters say it comes from the home town of co-founder John Carman, who came from Hemel Hempstead in Hertfordshire.

While Hempstead Turnpike is entirely contained in Nassau County (after leaving off its NY 24 designation at Broad Hollow Road in Farmingdale, it continues east as Conklin Street and Long Island Avenue as it pushes into Suffolk County), its Queens leg is little remarked on. The busy road begins at Jamaica Avenue and 212th Street at Litchhult Square, to be discussed presently, and pierces through Queens Village until attaining Turnpike status at the Cross Island Parkway and Belmont Park.

Unfortunately we have a couple of “Sick transit, Gloria” locations in Queens Village to talk about, as I like to call venerable buildings getting town down. The first is the Queens Lyceum at 99th Avenue and 218th Street, constructed in 1890 and used by social, cultural and political groups for over a century. In recent years it had been used by Veterans of Foreign Wars and as an Elks Lodge; but the building went up for sale and was razed in 2022, leaving only its flagpole; the latest Street View shows the flag raised next to en empty lot.

The Episcopal parish of St. Joseph’s was founded in 1870, with the present country church classic at 99-10 217th Lane dedicated in 1913. In recent years as the church building reportedly became unsafe, church leaders have wished to demolish the church, while preservationists want to repair it. At present, the church is holding online services while the building’s fate is in dispute.

217th Lane (there’s also a 217th Street and 217th Place) was Raywick Street until a few decades ago, but the tendency in Queens to number as many streets as possible won out.

This classic car appeared as if in a vision, as I staggered down Hempstead Avenue at 217th Lane. Anyone want to take a crack at identifying it? Comments are open.

Continuing on 217th Lane to the LIRR embankment wall, there are a couple of interesting things such as long ago artwork and a faded sign that says “Dump of New York,” but was there ever a dump here?

At many railroad overpasses the date of construction is cut into the embankment wall. This is very handy because those dates mark the time when the grade crossing was eliminated and the railroad was bridged over the cross street, as here at Hempstead Avenue.

Litchhult Square

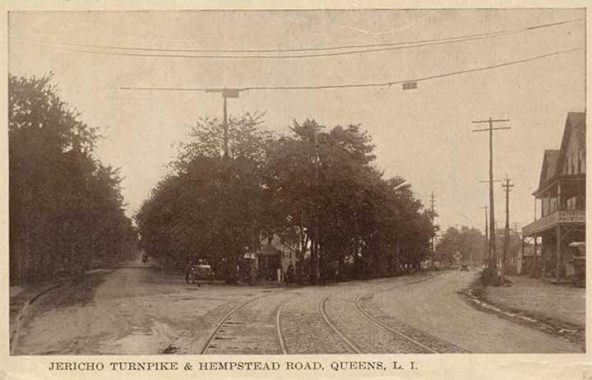

Here’s a look east at the junction of Jericho Turnpike and Hempstead Road in a postcard view between 1900 and 1910. Long Island Electric trolley tracks seen in the roadbed supported service until 1933. These two routes were narrow two-lane roads at the time. Look carefully and you can see a railroad crossing signal at right: this is the main line of the Ling Island Rail Road, which was placed on an elevated trestle in 1923.

At this point Jamaica Avenue from this point east was still known as Jericho Turnpike, for the mid-Nassau County town where it originally ended; it has since been extended to Middle Country Road in Smithtown, Suffolk County. From the early 1800s, Jamaica Avenue and Hempstead Avenue were known as the Hempstead and Jamaica Plank Road and was a toll road paved with wood planks. From the point today’s Hempstead Avenue diverged from Jamaica Avenue, the latter was called Jericho Turnpike.

About 1920, these roads received their current names, with Fulton Street in Woodhaven and Jamaica as well as the Hempstead and Jamaica Plank Road becoming Jamaica Avenue, and also Hempstead Avenue in Queens and Hempstead Turnpike in Nassau County.

From 1920 to 2005 the stretch of Jamaica Avenue between 225th Street and 257th Street that existed halfway in Queens County (the north side) and halfway in Nassau (the south side) went by two names: Jamaica on the north side, Jericho Turnpike on the south. After some years of pushing by the local organizations such as the Bellerose Community Civic and Community Board 13, the NY City Council decided to rename the north side Jericho Turnpike, and Mayor Michael Bloomberg signed the bill June 5, 2005; street signs were changed within a couple of months, giving NYC its second modern-day “turnpike” (after Union Turnpike.) The turnpike attained its present width in 1962.

Today Hempstead Avenue continues to diverge from Jamaica Avenue at the same point, and you can see the elevated LIRR trestle on the right. Hempstead and Hempstead Turnpike form NYS Route 24 and runs out to Route 110 in western Suffolk County. The triangle formed by Jamaica Avenue, Hempstead Avenue and 213th Street is now known as Litchhult Square, named for Lieutenant Andrew Slover Litchhult (1895-1936). He was a WWI veteran who fought in France and died years after WWI as a result of complications from encephalitis he contracted while fighting overseas during the influenza outbreak in Europe.

I found this classic VW “Bug” (with a bad paint job) at one of the many auto repair shops found long the eastern Queens stretch of Jamaica Avenue.

A cluster of yellow-bricked older buildings can be found on the north side of Jamaica Avenue between 212th Place and Hollis Court Boulevard. After many years, Village Plumbing still has its venerable plastic-lettered sign. If it works, why change it?

One thing has always perplexed me. The route of the Q36 bus, which runs from Merrick Boulevard to Jamaica, makes a north-south move to Hillside Avenue here, and buses use the narrow one-way 212th Street and 212th place. A block away, there’s the somewhat wider Hollis Court Boulevard (albeit with a center median.) Why don’t buses use it? Comments are open.

Hollis Court Boulevard exists in two separate parts, one in Flushing and Auburndale, running from 46th Avenue and Utopia Parkway southeast to Francis Lewis Boulevard and the Long Island Expressway, the other a 4-lane road with a center grassy median running from Hillside Avenue’s junction with the Clearview Expressway and Grand Central Parkway southeast to Jamaica Avenue. An intermediate section between 73rd Avenue and 86th Avenue adjoining Cunningham Park was renamed Hollis Hills Terrace in the 1970s.

At its southern end, it hosts some of the neighborhood’s more bespoken houses, as well as a Harley Davidson dealership at Jamaica Avenue, meaning it fits in with the motor vehicle theme. A larger dealership, New York Motorcycle, can be found further east at Jamaica Avenue and 222nd Street near the Cross Island Parkway.

The remains of the former Long Islands Rail Road Bellaire station can be seen on 211th Street just south of Jamaica Avenue. On the concrete embankment, you can see ghosts of the handrail supports for the staircase that went to the platform, as well as the supports for the platform on the trestle above 211th Street. )Similar supports can be seen at the former Elmhurst station at Broadway and Whitney Avenue.)

The Bellaire station was open between 1897 and 1972, so it lasted into modern history. It was elevated in 1924 as its grade crossing was eliminated.

Between 99th and Hollis Avenues, 211th Street gains a center median and has a clutch of twin double-mast lamps, which are getting rare in NYC.

Queens Village: Way-out Wayanda

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

6/25/23

12 comments

Old car looks to be a ’28 Hooter. Hooters were lousy cars and as the saying

goes you didnt have to worry if you saw one coming at you,as it would most likely

conk out before it hit you..

The photographer Walker Evans would have loved the Dump of New York sign.

He collected old faded metal signs,some so rusted and faded it was hard to make

out the lettering.He loved the beauty of decaying things

In the early 20th century brand names & emblems appeared on radiator shells, so if you don’t have that view cars of that era are difficult to identify. As a many-year subscriber to “Hemmings Classic Car” I can confidently tell you I’ve never encountered the brand name “Hooter”. However, here’s a photo of something that appears similar to what’s posted (but it’s located in New Zealand):

https://www.bing.com/images/search?view=detailV2&ccid=ml%2FoRO3O&id=597C4A5381EC8B19E5F804C43E2BDB067645B605&thid=OIP.ml_oRO3OG3WF84HP4L_B-wHaDt&mediaurl=https%3A%2F%2Fi.pinimg.com%2Foriginals%2F8d%2F04%2F26%2F8d0426dbd15eaf5e491885d15a2acdf2.jpg&exph=512&expw=1024&q=1928+hooter&simid=607995115666221497&form=IRPRST&ck=6E85D0E67DC09248BAA0E228D0C08C9B&selectedindex=7&ajaxhist=0&ajaxserp=0&vt=0&sim=11&cdnurl=https%3A%2F%2Fth.bing.com%2Fth%2Fid%2FR.9a5fe844edce1b7585f381cfe0bfc1fb%3Frik%3DBbZFdgbbKz7EBA%26pid%3DImgRaw%26r%3D0

It might be a slang term for a horn.

Thanks for the reminder of how difficult it is to read a FNY essay when you have domestic audio terrorists constantly going through my neighborhood streets with their illegal after market & modified parts on their noise machines. I’m typing this during a quiet moment.

Walter Kaner used his reputation and connections to a noble purpose. He created the Walter Kaner Children’s Foundation back in the 1970’s to assist disadvantaged children. The big event was always a Thanksgiving holiday party, where children were treated to a meal, a gift and entertainment. While he passed away in 2005, the foundation he started goes on. They have continued to host the Thanksgiving event, but also distribute grants to many local organizations, mostly in Queens, to further their work with economically and physically challenged children.

The National Rifle Association bought the Creed Farm in 1872 and held shooting competitions there until the early 1890’s.

They soon after moved to NJ because of development in Queens.

The area still holds some streets named Winchester and Springfield Boulevards and others.

The old car is a Ford Model A from 1928 or ’29. Great shape for a car pushing 100 years.

Old car looks to be a Ford Model “A”. Incidentally, the Green with Silver fenders paint job on the Volkswagen was an advertising gimmick for Kool cigarettes. They paid for the paint job and you had to drive it around for a couple of years with the Kool logo on the side.

Sure,Hooters were so obscure nobody has ever heard of them.The last Hooter

rolled off the assembly line(some would say towed off)in Saginaw Mich. in 1931.

They had a owl for a hood ornament whose eyes lit up at night when you turned

on the headlights.

The car in the photograph looks too large to be a Model A. However, the solution to its true identity would be an enlargement of the picture so that it would be possible to see the script/emblems on the center caps

Note to Chris: Please produce a picture & more information about the history of this mysterious brand “Hooter”. My search produces information about the famous bar/restaurant chain & a New Zealand limousine service, but nothing about a motor vehicle by that name. Only you can resolve this mystery.

Some swear that the Hooters marque really did exist while others scoff at

them and say that they are full of feces.

Whatever the case may be the old timers say that in darkest might and when

the Moon be bright the hills above Saginaw can still be heard to resound with

the clashing gears of old Hooters.

On Art Huneke’s site, that extra track on the eastbound side of the Queens Village station appears as a “drill track”. That is, an extra track off the main line with industrial sidings running off of it, so cars can be switched in & out of the sidings without fouling the main line. The 1924 blueprint there does show 3 siding tracks off the “drill track”, but I haven’t found a period street map to see what businesses they might have served.

See the bottom of this page: http://arrts-arrchives.com/BRUSHVILLE.html

Huh. Looking at Google Maps, the sidings are still there, a few blocks west of the station.

https://www.google.com/maps/@40.716835,-73.7393198,17.75z?entry=ttu