GUSTY winds and occasional showers are not my ideal walking conditions, but on the weekend, I’ll take what is offered, as I am working fulltime at home during the week. Luckily the plan was to walk all of Leonard Street in Tribeca, turn around and then walk all of Franklin Street going back, both easily done in a couple of hours. The street, whose house numbering runs east from Hudson to Centre Streets, is named for Leonard Lispenard (1714-1790), one of three sons of Anthony Lispenard, a wealthy 17th-century landowner who has his own street.

According to the Tribeca West Landmarks Preservation Commission report,

Leonard Street was laid out around 1797 as a twenty-seven-and-a-half-foot-wide street by Effingham Embree and ceded to the city in 1800. It was widened to its present fifty-foot width in 1806 and immediately developed with frame and masonry residences, none of which remain. By the 1850s the spread of commerce from downtown locations had transformed this street. Many houses were adapted for commercial occupants at the first story and received ancillary structures at the rear of the lot; other houses were replaced by small commercial structures, such as the brick building at No. 17 erected in 1855-56 for the Knickerbocker Ice Company.

Before jumping onto Leonard Street, take a look at this scene looking south on Hudson. One World Trade Center dominates, and the venerable New York Mercantile Exchange, built in 1886, can be seen at right. But my eye immediately went to a much-faded painted ad on the building on Hudson and Harrison Street. I can make out the top line, Geo. (for George) F. Wagner, but not the rest. Luckily, the Indispensable Walter Grutchfield has the answer. Wagner was a butter and egg wholesaler whose business was there between 1932 and 1949, so the painted ad, while old, isn’t as old as many of these ghosts around town. Southern Tribeca was home to many dairy wholesalers near the long-gone West Washington Market until the Swinging Sixties.

Even at its increased with of 50 feet, Leonard Street is still pretty narrow between Hudson and West Broadway, especially with parking on both sides. The incongruous, outrageous #56 Leonard (The Jenga Building) lords over all. I have complained about it but here’s a secret. I’m beginning to like it, especially seen from a distance. Right next to it? Not so much. Also, the Department of Transportation has vouchsafed to allow Leonard Street to keep its Belgian block paving on this block.

#7-9 Leonard Street is actually the back end if #155 Franklin Street. According to the LPC report, it’s an

irregularly-shaped building used as a provisions warehouse designed by prolific architect George W. DaCunha for Augustus C. Beckstein, a meat packer and real estate developer.

The building on the right, #11 Leonard, in 2015 replaced a pair of nondescript industrial workshops that had become garages.

#19-21 Leonard Street began its existence in 1868 as a police precinct and prison and was designed by Nathaniel Bush, who designed most of NYC’s police precincts in the era. Since 1918 it has been a commercial building used by Standard Rice Co., the Ronald Paper Co., the Hailer Elevator Co. (for storage and assembly of elevators), and the Empire Elevator Corp. and is presently residential. No doubt none of its occupants know it was once a precinct. The building has three entrances, #19, #19 1/2 and #21.

Much more from the reliable Tom Miller, the Daytonian in Manhattan.

#18 Leonard Street between Hudson Street and West Broadway has a relatively new painted sign advertising it as The Juilliard Building. It was built in 1883 and at one time was occupied by H.B. Claflin & Company, the country’s largest wholesale dry-goods store; its retail store on West Broadway is long gone. The building was originally owned by Helen C. Juilliard, the wife of Augustus Juilliard, a millionaire made rich by his dry goods and banking businesses. Mrs. Juilliard was a philanthropist who was especially interested in the plight of poor and malnourished children. She helped fund the first Floating Hospital:

The Floating Hospital was a revolutionary concept in the late 1800s, turning the routine occurrence of quarantine barges into a health excursion that combined medical care, healthy eating, and entertainment into one experience. Aboard the Floating Hospital, patients and visitors enjoyed puppet shows, dancing, sing-a-longs, art classes, games, celebrity appearances and movies. They snacked and lunched as they spied breathtaking views of sea and city. No wonder it was nicknamed the Happiest Place on Earth. In the wake of the success of the first Floating Hospital, the first Helen C. Juilliard ship launched on May 4, 1899. [Granby Drummer]

The Juilliard School of Music in Lincoln Center was established in 1905 and was funded in large part by a bequest from Augustus Juilliard.

The New York Law School‘s glass tower addition (2009, SmithGroup) dominates the SW corner of West Broadway and Leonard. There are four underground floors.

The school was founded by Columbia law school professors in 1891. The main school is at nearby 57 Worth Street.

The smallest diner I have ever been in, and the smallest booths I have ever sat in, can be found in the Square Diner at Varick and Leonard Streets. The building is actually an uneven rhomboid, not a square. Though a diner has been on this plot since 1922, the diner building itself was built in 1947; still fairly venerable. I was glad to see it open after a closure during the Pandemic.

From New York Magazine:

As if it dropped into town right out of Central Casting, the Square Diner is a den of mid-century, blue-collar charm in the midst of 21st-century Tribeca. The chrome-age exterior, like a train car or a World’s Fair ride, is the first indication that the diner will have you stepping back in time. Inside, the restaurant takes on a bit of an Art Deco nautical theme, with polished wooden bead-board on the ceiling and porthole-like mirrors along the back wall, just below the row of celebrity headshots that all look like they date from the mid to late eighties.

For interior views and some more history, see this FNY page.

I spotted this painted ad in a classic chunky type font from 1996 at #175 West Broadway, south of Leonard. I assumed New York Design Architects was long out of business, but they are still going strong and own the building.

If you have never heard of Finn Square, that’s perfectly understandable. In NYC parlance, a “square” can be any shape, and Finn Square is a triangle in Tribeca formed by the intersection of West Broadway and Varick and Franklin Streets. Officially, there’s no actual neighborhood called Finn Square, but in my opinion there’s enough distinctive architecture and unusual surviving artifacts to designate it as a distinct region.

On the Lower West Side of Manhattan, there are two separate street grids, one that hews to a general east-west-north-south orientation (though Manhattan Island runs a little northeast against true north) and a diagonal grid that begins just north of Canal and runs north to West 14th. This grid is positioned so it runs perpendicular to the Hudson River shoreline. (There are variations in orientation of this diagonal grid in he West Village, especially between Christopher and Bank.)

Where these two grids meet, there are interesting intersections and streetscapes. West Broadway acts as the barrier between the two from Chambers north to Canal, with 6th Avenue dividing the two grids from Canal north to West 8th since it was extended south from Carmine Street beginning in 1928.

Finn Square actually honors two Finns. The first was a Tammany Hall politician, Daniel E. Finn (1845-1910), known as “Battery Dan” for his success as an assemblyman in the First District for helping block a plan to build piers along the west shore on Manhattan in Battery Park. The piers were not built and Battery Park remains to this day a much-needed open space relief from the beetling towers of lower Manhattan. As a judge, Finn was known for protecting the public against Police Department excesses.

Although in actuality Finn Square was named for “Battery Dan,” officially it is named for his son, Philip Schuyler Finn, a member of NY’s Fighting 69th Regiment, who perished in World War I. The square itself was created shortly after the war, when Varick Street was given a southern extension past Franklin Street to meet West Broadway.

Every year, a new modern artwork makes its way to the tip of Finn Square at Leonard Street; in March 2024 it was Joan Benefiel’s “Hoodoos.” I don’t mean to make fun. OK, maybe I do. Most modern art to me looks like something I can do. But, if you have made a name in modern art circles, you can create things that nearly everyone can do.

I am a Philistine.

Some free advice on a dumpster on Leonard east of West Broadway.

Church Street, which runs from Liberty north to Canal, skirting the east edge of the World Trade Center complex, has retained the look it had decades ago (with one glaring exception below), with stolid, neo-Renaissance office buildings. This one, #66-70 Leonard at Church, has been known as the Textile Importers’ Building and the Textile Building, was constructed in 1901 and designed by the prolific Henry Hardenburgh.

That exception is #56 Leonard, affectionately called the Jenga Building; it appears to have been designed by Monty Python’s Royal Society for Putting Things On Top Of Other Things

The 57-story skyscraper boasts 145 condominium residences priced between $3.5 million and $50 million and was designed by 2001 Pritzker Architecture Prize winning Swiss architects Herzog and deMeuron (see interior photos at the link). It was built in stages between 2008 and 2014. In 2023, a replica of the Chicago sculpture by Anish Kapoor, “Cloud Gate,” popularly known as The Bean, was installed on the Church and Leonard Street entrance. Kapoor himself owns an apartment in the building.

I had never heard of Lorenzo da Ponte. Then again, I wasn’t a classical music fan, so I had no knowledge of the Italy-born poet, opera scorer and Mozart collaborator (1749-1838). The musician later moved to New York, where he was when he passed away. My question is, his name is on a street sign here, but with no “Place,” “Way” or any other street identifier.

However this seems to be an error by the Department of Transportation sign shop because an earlier sign did indeed have a “Way” on it. da Ponte’s final resting place is in Calvary Cemetery in Blissville, Queens.

I haven’t yet tried Two Hands Restaurant, on Church just north of Leonard; it’s favorably reviewed. I’m featuring it here, though, to express my frustration with restaurant gutter sheds, as I cannot get a decent picture of this place and hundreds of others around town because of the sheds, which arose as indoor dining was limited during the Pandemic. Do restaurants still depend on them in the postpandemic era?

#72-78 Leonard, handsome grouping of loft buildings developed in the mid-1860s. Note the rows of Corinthian columns in the front.

Once you get past midblock on Leonard between Church and Broadway, you’re out of the Tribeca West Landmarked district, meaning the buildings you see here are unprotected. I don’t know why, though, they’re from the same era or thereabouts, and have a unity of appearance.

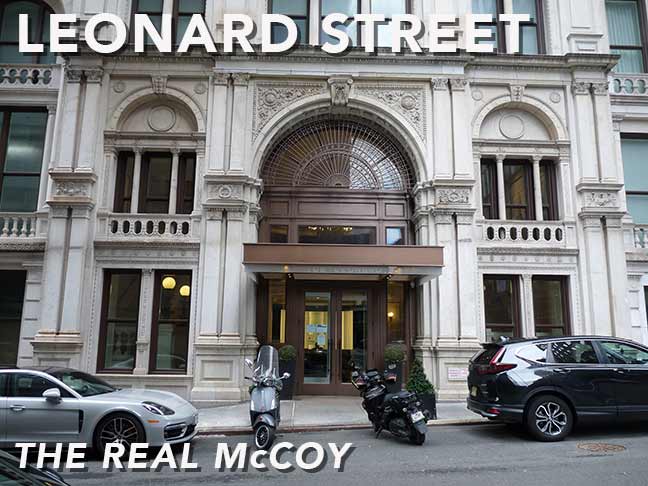

A magnificent building from any era, the New York Life Insurance Building (completed in 1898; now known as the Clock Tower Building) is one of Tribeca’s magnificent structures. It occupies an entire city block, an uneven rhomboid between Broadway, Leonard and Lafayette Streets and Catherine Lane. From the LPC Designation Report:

The home office of the New York Life Insurance Company, organized in 1841 and one of the oldest life insurance companies in America, was constructed between 1894 and 1898. A monumental freestanding skyscraper in the neo-Italian Renaissance style, it was designed by Stephen D. Hatch and McKim, Mead &White. The design history is extremely interesting, and somewhat complicated. In a sense, the building was constructed “backwards”. The eastern rear section designed by Hatch was originally intended to harmonize with the old New York Life building of 1868-70, then located at the western end of the block. When Hatch suddenly died, the commission was turned over to McKim, Mead &White and under their supervision the project took on new dimensions; the old building was demolished and the new building, now culminating in a palazzo-like tower on Broadway, was carried to completion. Thus two separate campaigns resulted in the unified and impressive structure we see today.

Among the building’s “Easter eggs” are a flock of eagles on the roof, mostly invisible to all except those in opposite floors of neighboring buildings. The clock on the roofline has to be wound by hand twice per year to gain or lose an hour.

After 20 years, the public finally gets a llok at what Catherine Lane looks like. The alley connects Broadway and Lafayette Street on an angle along the south side of the New York Life Insurance Building. There’s nothing to write home about here, though, save the entrance to a parking garage, and maybe one of the griffins on the ground floor of 344 Broadway. Before the scaffold was installed in the 1990s, I recall a scrolled wall lamp, but that has disappeared in the interim.

I’m attracted to alleys. Benson Street used to be a dead end on Leonard east of Broadway, but a narrow part was built through to Franklin Street and it was rebranded “Benson Place.” Likely an error by the Department of Transportation sign shop. I cover it, as well as Catherine Lane, a bit more fully in FNY’s One and Done series.

Here’s the impressive side entrance of the New York Life Insurance Building at #108 Leonard Street.

This neo-Classical building just north of Foley Square at Lafayette and Leonard (with a Worth Street address) houses the New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, and the New York City Sanitation Department. It’s a somewhat stolid and boxy, and was originally simply the Department of Health Building when it was completed in 1935 (Charles B. Meyers, architect). It’s easily ignored unless you need a copy of your birth certificate, since the NYC Office of Vital Records is also located here.

Yet, you have to give it a chance – keep looking up, as optimists say, and you’ll be rewarded with some unusual sights. The building, which takes up an entire block, is ringed with stop-sign shaped spandrel ornaments depicting people engaged various forms of work, some of which is associated with the medical profession. In one, a man tends to a presumably experimental rat in a cage; another shows another fellow mixing a prescription in a mortar; another shows a woman wrapping a wound on a child’s thigh. A man harvests wheat, while another catches fish with a net.

Look further up, and just below the seventh floor, the building is ringed with carved last names (or single names) of important names in medical research throughout the centuries: on the Worth Street side is found (Edward) Jenner, 18th Century vaccination pioneer; (Bernardino) Ramazzini, 17th-18th Century discoverer of quinine’s use in treating malaria; Hippocrates, 4th-Century B.C. founder of the Hippocratic School of Medicine in classical Greece; Paracelsus, the 16th Century German founder of toxicology; (Philippe) Pinel, the 18th Century French “father of psychology”; and (James) Lind, the 18th Century Scottish physician who used citrus juice to treat scurvy, which was rampant aboard British naval vessels.

Among the other names carven into the faced are those of (Florence) Nightingale, recognized as the founder of modern nursing; (Joseph) Lister, developer of antiseptic surgery; (Louis) Pasteur, vaccination pioneer and developer of pasteurization to prevent contamination of milk products by bacteria; and (Major Walter) Reed, who discovered that yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes.

Seen from Lafayette Street, the forboding weather seems fitting for a look at 100 Centre Street, The NYC Criminal Courts Building and House of Detention, the erstwhile “Tombs.” In 1838, the first of the buildings known as “The Tombs” was constructed. The original Tombs was the setting for the last scene of the Herman Melville classic short story “Bartleby the Scrivener.” This building was built 100 years later in an Art Moderne style.

Collect Pond was a large, freshwater pond just north of today’s Foley Square later made brackish by local industry; it was drained after 1816 by a canal that is now located in a sewer beneath Canal Street). The name is another instance of the British wrangling a Dutch term into something nore euphonious to English speakers; “collect” came from “kalck,” or lime, referring to the oyster shells that were found when it was a freshwater lake. Plaques tell the story of the pond as it was when colonials found it and its subsequent degredation and disappearance.

Collect Pond Park was reconstructed in 2011 and the ever-ready Sergey Kadinsky had the story.

In 1980, the easternmost section of Leonard Street between Centre and Baxter Streets was renamed (not subnamed) for Frank Hogan, Manhattan district attorney who died in 1974 after 34 years in office. The street is located between the Louis J. Lefkowitz State Office Building and the Manhattan Criminal Courts Building.

Next time, Franklin Street

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

3/17/24

5 comments

I left this comment on the Facebook post, but it probably wouldn’t hurt to leave it here, either.

Always good to see another post from you — and one which mentions not one, but TWO works of Charles B. Meyers, architect! Both the former NYC Dept of Health building AND the Criminal Courts/Tombs building were designed by Meyers — although the latter was designed in collaboration with Harvey Wiley Corbett.

I’ve done some considerable research into Meyers’ body of work, going so far as to make a map of extant and demolished structures to his name per the old records. The oldest building of his still surviving is at 274-276 Mott, just south of East Houston Street, built in 1898, whilst his last construction was in 1957, a year before his passing: a Nurses’ Home and Training School at 1918 First Avenue, part of the modern Metropolitan Hospital. That building, too, still stands, albeit its façade has changed and it’s been expanded in recent years. The most productive span of time in his career, I’d say, lasted from 1908 to 1913, averaging about 24 building plans (off his designs) approved per year over that five-year span.

Funny little quirk I’ll mention, though — there’s a considerable cluster of buildings along 35th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues — 212, 224, 240-246, and 248-252 West 35th Streets — as well as 462-468 Seventh Avenue, 472 Seventh Avenue, AND nearby 202 West 36th Street — which were all designed by him within a four-year span, between 1921 and 1924. All within extreme proximity to one another, and probably some of his tallest buildings to date, to my knowledge.

Addendum that I didn’t leave on the FB comment version of this — I know this isn’t really the focus of this post of yours; the beautiful buildings of Leonard Street are, and oh-how-lovely is this history. But I just figured I’d share with you some of my own research, frankly inspired by your works. My parents picked up a copy of your book back when it was new back in 2006, and I think it ingrained within seven-year-old me a sense of utter wonder about the history of the city. Did a whole bit of history on my own building just this past December — one of Meyers’ works, itself, which is how I learned about him in the first place — that I shared with the other residents, in which I acknowledged you as a key inspiration in this journey of research. Frankly, I’m thankful that you’re still writing these posts and going on these walks, all in all. Thanks, Kevin, for keeping this city’s history alive in our minds.

It’s interesting that this street was named after a person’s first name when it’s usually after their last name.

I always thought they had closed the Tombs down since that bad riot around 1970.Apparently

they didnt

While attending college in the mid-60’s, I worked summers at Western Union 60 Hudson St. on 2nd shift. Frequently I worked overtime at time-and-a-half (a big $3.75/hr!). Since I’d eaten my lunch sandwich at 8PM, I would take my 3AM break and walk down West Broadway to the Triangle Diner to get something to eat.

Collect Pond eventually was taken over by the Five Points.