By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

HAVING documented post-millennial changes to the streetscapes of Melrose and Mott Haven, one would not expect much to change on the Grand Concourse, the boulevard of stately prewar apartment buildings.

But on the lowest part of this road much has changed in recent years, transforming a once-industrial strip of car repair shops to high-rise residences and hotels. A half-century before they arrived, Hostos Community College was the transformative institution on this stretch of the Bronx’s defining roadway. And more than a century ago, it was a collegiate gothic public school that had the same visual effect.

At the corner with East 149th Street, the landmarked Bronx Post Office did not need a sizable building in this century and it was sold to developers, with a smaller postal presence inside the building. The facade sculptures by Henry Kreis and interior murals by the married couple Ben Shahn and Bernarda Bryson are safe for future generations to admire. One positive element of the building’s privatization is that the rooftop is open to the public as it hosts the restaurant Zona De Cuba with its tropical ambiance that offers views of the city.

On the opposite side of the Grand Concourse was a Dunkin Donuts that has been paying the rent at this corner from 2016 until 2024. The rooftop billboard has been here for decades, promoting lawyers, phone plans, and insurance, among other things. During my visit, it’s the injury law firm Harris, Keenan & Goldfarb with a slogan inspired by hip-hop trio Naughty by Nature. I don’t know if attorney Seth Harris raps, but his career had its start in this borough where he represented poor clients and taught law to seventh graders.

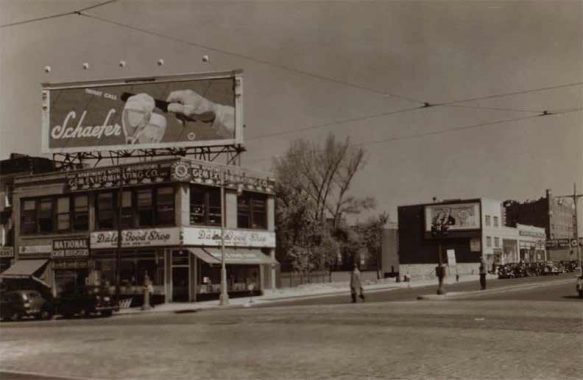

A tax photo from 1940 shows this corner having a public clock, courtesy of Gem Exterminating company. The ground-level storefront was a bakery at the time, a role later fulfilled by Dunkin Donuts. On the billboard is an ad for Schaefer, the beer brand that was brewed in Brooklyn until 1974. Further back is a wall ad for Esso, the forerunner of Exxon, whose name was an abbreviation of Standard Oil that made the Rockefeller family astronomically wealthy. In its place during my visit was a fading mural ad for an injury lawyer. It is partially covered by a retail strip built in 2007 that deserves points for using bricks instead of the boring concrete or glass that predominates in this period.

On the southeast corner of this busy intersection is a preserved wall of the old entrance to the 149th Street-Grand Concourse station, marked as “Mott Avenue,” the old name for the section of the Grand Concourse between 138th and 161st streets. Good that it was renamed to prevent confusion with another Mott Avenue station in Far Rockaway. Don’t feel bad for its original honoree, as he has the neighborhood of Mott Haven carrying his name. Inside this subway station, Kevin found mosaic lettering of its old name and a sign for a commuter train station next to it that was never built. This station was a popular hangout among graffiti artists during their heyday of vandalizing subway cars.

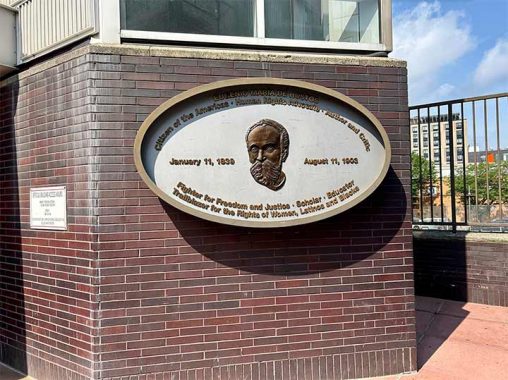

Behind this old wall is the main building of Hostos Community College. A product of the civil rights movement, it was founded in 1970 following demands by Puerto Rican activists to create a college in the heart of their community, similar to the mission of Medgar Evers College in Crown Heights that has a similar role in that historically Black neighborhood. Namesake Eugenio Maria de Hostos was a Puerto Rican patriot who promoted independence from Spain and a union of its former Caribbean colonies as a federation. He died in 1903 in Santo Domingo with the final wish to be reburied in Puerto Rico upon its independence. It’s unlikely to happen but since then he’s become a hero on the island and its diaspora for his activism and role as an educator.

The mural of Hostos in the entrance lobby was by artist Rafael Rivera Garcia on the sesquicentennial of his birth. It was recreated in the lobby for the college’s 50th anniversary in 2020 by alumna Alice Curiel Baldonado.

The present building dates to 1988, when CUNY had an ambitious master plan for Hostos: twin buildings connected by an enclosed footbridge. In this regard, the design is reminiscent of Hunter College on the Upper East Side and Midwood High School in Brooklyn. Hostos’ bridge was not only designed to connect buildings, it was to function as a “campus quad,” with seats on the bridge for students to take breaks.

Designed by the firm Gwathmey Siegel Kaufman, the campus has the standard amenities of a respectable college: a swimming pool, gym, cafeteria, art gallery, theater, labs, classrooms, and offices. It was a welcome improvement compared to the original facility of the college.

Its first classrooms were inside a former tire factory and when the city was on the brink of bankruptcy in 1975, the college nearly closed if not for the activism of the Puerto Rican community. Since then the college has expanded to 11 buildings within a short distance from each other.

Evelyn Antonetty Playground predates the establishment of Hostos Community College but it is now enveloped by its buildings in the same manner as Washington Square Park is the center of New York University. The park’s name was assigned in 2011 in honor of a Puerto Rican-born political and labor activist who founded United Bronx Parents. It had a reconstruction in 2020 that replaced most of its paved space in favor of more greenery.

The park was built in tandem with the Lexington Avenue subway line, in which the uptown 5 train departs from Grand Concourse and makes a jughandle turn to 149th Street. The parcel above the split in the tracks became parkland. Its prior name was Garrison Playground, in honor of the famed abolitionist whose name also appeared on the adjacent P.S. 31. Don’t feel bad for William Lloyd Garrison as his name still appears on an avenue in Hunts Point.

The high-rise at 425 Grand Concourse is the tallest building on this queen of Bronx roads, completed in 2022. It contains market-rate and reduced-rate apartments, and offices for Hostos Community College. It is as much a symbol of the area’s post-millennial transformation as the Bankside complex in Mott Haven and the new Yankee Stadium.

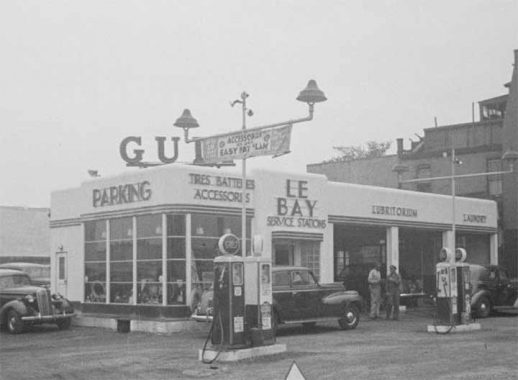

Older Bronxites remember this site for its “Castle on the Concourse,” the long-abandoned public school designed by the great C.B.J. Snyder in 1899. Designated as a city landmark in 1986, its future seemed certain but instead it continued to deteriorate and was closed in 1997. In early 2013, one of its walls collapsed, with bricks falling onto the neighboring playground. Its fate was then sealed, with the landmark status removed and the demolition approved. In this old photo from the NYPL Digital Collections, we see the school, playground, and a Tydol gas station on the future site of Hostos college. Tydol was an abbreviation of Tide Water Oil Company, a brand that fell into disuse by the 1950s.

This high-rise is not open to the public but that hasn’t stopped me from trying so I went in to explore this postmodern giant. At the Hostos advisement office on its ground floor is an artifact of P.S. 31 that was salvaged during its demolition. The Landmarks Preservation Commission recommends that when a building is delisted and razed, that remnants of it be incorporated into the new structure. Perhaps there are other artifacts from C.B.J. Snyder but I did not see them on my visit.

The seating, artworks, and lampshades in this lobby are worth a stay. It felt like a living room rather than a semi-public space.

In the elevator bank are a photo of the late P.S. 31 and three Bronx-themed collages by artist Johanna Goodman, titled New York Botanical Garden, Birthplace of Hip-Hop, and Local Subway.

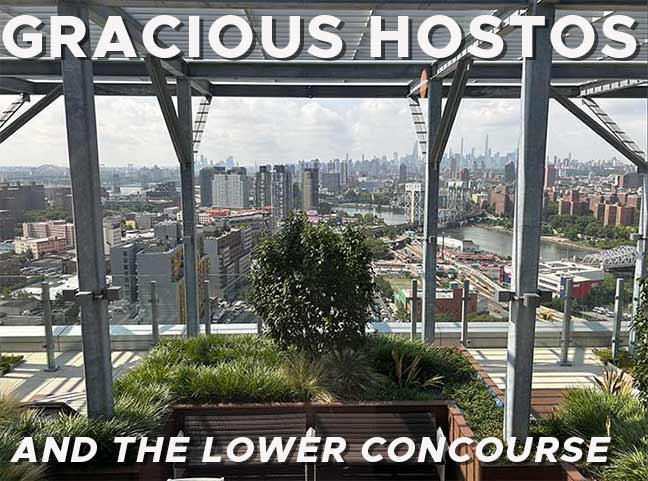

Paraphrasing local rapper Fat Joe, I took the elevator “all the way up,” and was rewarded with a view looking downtown underneath a massive pergola. The greenery here had an impressionistic feel and with recognizable elements like the Park Avenue railroad bridge, it was like a Daniel Hauben painting.

Old architecture that once accompanied P.S. 31 can be seen in the tenements across the street that frame the two-eyed transit substation. It is likely that when these buildings were constructed in the early 20th century, their addresses were on Mott Avenue before it was incorporated into the Grand Concourse. Coming from Queens, the street layout is reminiscent of Queens Boulevard, which runs at its full width from Sunnyside to Queens Borough Hall, and is then reduced to one traffic island for its final mile. With the Grand Concourse, its southernmost mile is relatively narrow but then at Bronx Borough Hall it widens significantly. Kings Highway in Brooklyn also begins with two lanes and then becomes wider on its way east.

The rowhouse at 382 Grand Concourse is an architectural holdout. If it could come to life and speak, it would describe how much the streetscape here has changed, from being the northern outskirts of the city, to a manufacturing district with a railyard behind it, to its current transformation with residential high-rises.

Teddy’s Place Auto Repair is also the last of its kind on the Concourse, harkening to the recent past when nearly every business south of 144th Street was a garage, storage facility, or a gas station. I don’t expect it to survive this decade. It is sandwiched between a hotel and a luxury rental tower.

On this stretch of Grand Course are street signs of the Bronx Walk of Fame honoring local greats. Dion DiMucci was the frontman of The Belmonts who emerged from Arthur Avenue and helped make doo-wop popular in the late 1950s.

John “Jellybean” Benitez is the deejay who made New York synonymous with freestyle music. There was a time when WKTU radio seemingly played this genre nonstop. Can you feel the beat? But now it’s Silent Morning as the station mostly plays other things. Jellybean is best known for his 1984 breakout hit The Mexican, an early freestyle chart topper.

The residential towers here were so new that they haven’t yet hired doormen so I walked in to check out the art and views. 310 Grand Concourse has an Escher-like cityscape in its lobby. For the post-Covid work-at-home residents, this building has a “business” room for printing, meetings, and quiet work. It also has a lounge, gym, game room, and yoga room. 24 of the units here were offered at below-market by lottery.

From its unfinished rooftop, I looked north at the Melrose Wye where the Hudson and Harlem lines diverge. The hulking brown structure is Lincoln Hospital. On the horizon are the Concourse Village apartments that were built for members of the meat cutters and butchers union.

Looking southwest towards Manhattan, below is the ramp connecting the Grand Concourse to the Major Deegan Expressway and cleared lots next to it that will soon have their own luxury towers to block my view.

At these vacant lots the bedrock of the Bronx protrudes the surface, as this is the rockiest of the boroughs and the only one on the continental mainland. Soon enough, these rocks will be blasted and covered by more buildings.

These towers are creative inside but the outside walls are relatively uninspiring. At 276 Grand Concourse the bricks spell out the name of this road, a small measure of creativity by the architect. Come inside and gawk at the interiors. You won’t believe that this is in the South Bronx!

Grand Concourse is better known for its underpasses as it runs atop a ridge for most of its route. At its southern beginning, the ramp connecting it to the expressway is a long stone-covered arch spanning 138th Street with the heraldic symbol of The Bronx.

Also at 138th Street is the subway station next to an opioid clinic run by the nonprofit Samaritan Village. Mosaic tiles on the platforms indicate the neighborhood as Mott Haven. In 2021, Squire Vickers’ tiles were cleaned up and a new artwork was added to this station, Amy Pryor’s Day Into Night Into Day, a set of five mosaics relating to the four seasons of the year.

Prior to the popularity of cars and the arrival of the subway to the Bronx, this corner hosted an elaborate train station on the New York Central lines. Completed in 1886 it shared the Richardsonian Romanesque design of Albany City Hall and the New York State Capitol. Its earthy masonry also reminded me of the LIRR station in Forest Hills. Had this station house survived to this day surely it would have been landmarked.

It was sold by the financially strapped railroad in 1964 and unceremoniously demolished within two years. The platforms here picked up their last passengers in 1972.

It felt ironic that I had access to two high-rise rooftops on that day, but not the skybridge at Hostos Community College. Having documented the architecture of the CUNY community colleges in eastern Queens and southern Brooklyn, I hope to return and see more artworks inside this campus.

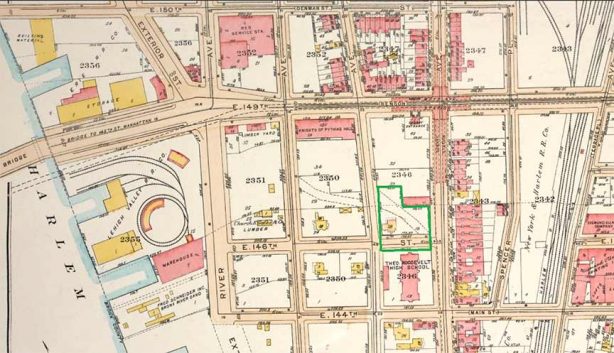

As with some of my previous essays, a map tour into the past reveals how much the vicinity of Hostos Community College has changed. On this 1921 Bromley atlas, I outlined Evelina Antonetty Playground in green. To its east are a few remaining wooden houses from the 19th century and docks along the Harlem River. 149th Street had the Bronx chapter of the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization. Snyder’s Castle on the Concourse was Theodore Roosevelt High School which moved uptown to Fordham Road in 1928.

Finally, Spencer Place, which was renamed in 1936 after Anthony J Griffin.

A final photo that speaks of the transformation is the 1940 tax photo of the Gulf gas station at 490 Grand Concourse, which was later developed for Hostos’ B Building. It was a beauty of Art Deco design. Note that it had a lubritorium and laundry.

You can learn more about this neighborhood by visiting each of the hyperlinks posted in the essay above.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

8/3/24

3 comments

The Bronx Central Post Office has a footnote in one of New York’s most notorious crime stories. David Berkowitz, the infamous Son of Sam who killed or wounded at least a dozen people in his 1976-77 crime spree, worked for the US Postal Service at that very location when he was captured in August 1977 – exactly 47 years ago this week. At the time I, my wife, and then-toddler son lived in Queens near some of Berkowitz’s crime scenes. It was a scary time, for sure. My wife and I breathed a sigh of relief when Berkowitz was arrested. He remains in prison to this day.

1) “For the post-Covid work-at-home residents, this building has a “business” room for printing, meetings, and quiet work.”

2) “cleared lots next to it that will soon have their own luxury towers to block my view”

Alas, the existence of 1) likely means that 2) won’t happen.

I’m surprised that you were just able to go up to the rooftop of those apartments for views considering that they are private property.