In early February 2025, a month that was generally cold with at least some snow, unlike recent winters, I took advantage of a relatively mild Saturday and walked Jamaica Avenue from the Van Wyck Expressway east to 165th Street, the heart of Jamaica itself, a town founded by the Dutch (as Rustdorp. “peaceful village”) in the mid-1600s. Jamaica, an English transliteration of “Jameco,” the Indian tribe that lived near what is now called Jamaica Bay. Jamaica originally included all lands south of the present Grand Central Parkway (which explains why Jamaica is so far away from Jamaica Bay). “Jameco” comes from the Lenape word for “beaver” and the rodent, much prized for its fur, was frequently found in the area. Beaver Road in Jamaica was named for the road leading to the now-infilled Beaver Pond.

Jamaica Avenue has been well-covered in Forgotten NY, both in Brooklyn and Queens, but today I decided on making a “one stop shopping” page for its most celebrated stretch.

I took the E train from Roosevelt-74th Street to the Jamaica-Van Wyck station. It is one of only 6 11 new MTA subway stations opened between 1950 and 2017 (see Comments). Jamaica-Van Wyck, Sutphin Boulevard-Archer and Parsons-Archer opened in December 1988, while 63rd Street, Roosevelt Island and 21st-Queensbridge on the F line opened the same year. These stations began construction in the 1960s and 1970s and exhibit 1970s design esthetics, such as burnt orange coloration, all the rage in that era.

The station is an eastern extension of the E, where it branches from the F at the Van Wyck Boulevard-Briarwood station, and the J/Z, east from 120th Street ten years after the Jamaica El east of that station ended service.

The 1988 station did receive a brick stationhouse that serves mainly to shield the down escalators. Street-level escalators are still a rarity with NYC subways; when I visited Washington DC, I was surprised to find so many on the Metro. I did like the Type B park lamp that was added and holds a number of traffic signs.

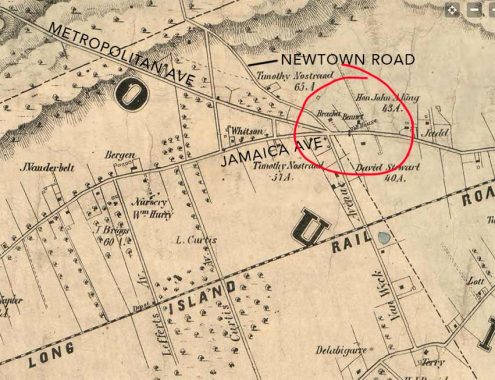

The stationhouse is at a (surprisingly) unnamed intersection at which you will find four of Queens’ oldest roads. They had already been in place for decades when this Dripps 1852 map was drawn up. The Jamaica Plank Road (Jamaica Avenue); Williamsburg(h); Jamaica Turnpike (Metropolitan Avenue); Whitepot Road/Newtown Road (Kew Gardens Road); and Van Wyck Avenue (since lengthened and upgraded to a Boulevard and then an Expressway, all converge here.

Amusingly the tire shop on Kew Gardens Road is called “The Cats”; there must be a story there.

The newest street fixtures the Department of Transportation has trotted out are these pedestrian light controls. Some are painted yellow, some gray, as you see, and some are black. Like the pushbuttons of old, they don’t actually change the lights. Meant to help the visually impaired, pressing the button activates a “wait” voice when the signal is red.

Jamaica Hospital, Jamaica Avenue and Van Wyck, was founded in 1891, with this building (since rebuilt and expanded) opened in 1924. The most celebrated birth is one Donald John Trump.

I am always on the hunt for classic NYC storefronts and signage. Pehnke Insurance qualifies; this sign has likely been in place for decades, as it gets the job done. According to one source, Pehnke has been in business since 1952.

I am so fasacinated with Queen’s House, Jamaica Avenue at Queens Boulevatrd, I shot it three times.

Queens Boulevard is possibly the fastest and furious-est, most pedal to the metal grade level road in Queens, other than an expressway. It roars from the tangle of elevated train tracks at the east end of the Queensboro Bridge through Sunnyside, Elmhurst, Rego Park, Forest Hills and Kew Gardens, finally petering to a close as a modest two-lane road at Jamaica Avenue after running ten lanes for much of its route and having acquired the nickname the “Boulevard of Death” for its pedestrian-unfriendliness.

Before the arrival of the Queensboro in 1909, Queens Boulevard was a modest country road known as Thomson Avenue and then Hoffman Boulevard, and before the coming of the white man to Queens it was likely a trail used by the original residents. The bridge brought new residents to the borough, and finally the overwhelming popularity of the auto spurred its widening and redevelopment in the Roaring Twenties, development which was also applied to Trotting Course Lane (to become Woodhaven Boulevard) and Kings Highway in Brooklyn. The country lane became a 10-lane megaroad.

Between Hillside and Jamaica Avenues at the edge of Briarwood and Jamaica, Queens Boulevard is reduced to much the same condition as its ancestral roads, narrowing to two lanes. It’s mostly a nondescript stretch with collision and auto body shops.

A handsome apartment house, with Flemish-style steps on the roofline and a rounded corner, would seemingly put it more at home on the Bronx. But an inscription on the Jamaica Avenue side makes it indubitably clear that we’re not in the Bronx … Queen’s House. Are we looking at a marvelous coincidence — was the building constructed before Hoffman Boulevard became Queens Boulevard? Or, was the house at the end of Queens Boulevard built and inscribed with an apostrophe the name of the boulevard doesn’t have?

The mists of time have obscured the answer.

El Reconcito Paisa, Jamaica Avenue at 139th Street, is decked out in Colombian flag colors.

I lied the sky blue exterior panels on this BMT subway powerhouse on 144th Place south of Jamaica Ave.

Rows of storefronts along Jamaica Avenue between 144th and Sutphin Boulevard in brick and terra cotta may have had the same developer. That laundromat sign appears several decades old. You can find an Irish dive bar anywhere in NYC and “The Blarney” is in the middle of South American-Caribbean-African-American Jamaica.

Like the Ridgewood Savings Bank at Queens Boulevard and 108th Street, the Jamaica Savings Bank (now a Capitol One branch) at Jamaica Ave. and Sutphin Blvd. is a prime piece of limestone-cladded Moderne architecture. It was constructed in 1939, designed by architect Morrell Smith and still has its simple bas relief eagle and stars on the exterior. Unfortunately its original brass door has been replaced. I haven’t been inside; I always seem to be here on the weekend, but inside is a mural painted by Earl Purdy depicting a scene at Jamaica Avenue and Parsons Boulevard a few blocks to the east. (If you can sneak a photo of the interior without getting the bum’s rush from the guards, please pass it along.)

A completely different design esthetic was applied to another Jamaica Savings Bank in Elmhurst.

I think this pair of storefront blocks on both sides of Jamaica at 148th Street are spectacular molded terra cotta. As you can see zoning went haywire in Jamaica and buildings of incongruous size are springing up like tulips in spring. The high rises are giant residential buildings on Archer Avenue next to the busy Jamaica LIRR station, where most lines converge as well as the AirTrain to JFK Airport.

C.H. Martin is a chain of discount stores in the NYC metropolitan area. Information about the company, including who C.H. Martin is, is apparently held close to the vest by the owners. The company website appears to have been constructed in the mid-1990s.

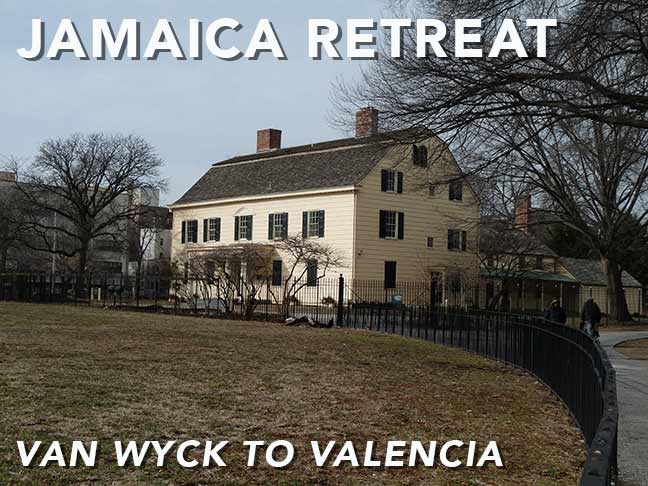

King Manor

Are we really in Jamaica? Yes, we are. The Rufus King Mansion, more properly, King Manor, stands on Jamaica Avenue and 153rd Street. It was originally built in 1730 along the main route to Brooklyn Ferry at the foot of today’s Fulton Street. In 1805, Rufus King (1755-1827), who was born in what is now Maine but was then part of Massachusetts, bought and expanded the property to its present appearance. A bona fide Founding Father, he was a youthful representative at the Continental Congress from 1784-1786, a US Senator from New York in 1789, a Minister (Ambassador) to Great Britain from 1796-1803 (where he impressed the still-hostile Brits after the close of the Revolutionary War), a US Senator again from 1813 to 1825, and ran unsuccessfully for President as a Federalist against James Monroe in 1816.

King, an ardent opponent of slavery, argued: “I have yet to learn that one man can make a slave of another and if one man cannot do so, no number of individuals have any better right to do it.”

After Rufus King’s death in 1827, his son, John A. King, a congressman and NY State Governor, occupied the property, and it stayed in the family until the death of Rufus King’s granddaughter Cornelia in 1898. The Manor subsequently passed into City ownership in 1898, but it wasn’t until 1992 that it became a full-fledged museum. Presently, King Manor features historically active period room settings, including some objects owned by the King family, and public events and concerts are held periodically. Archeological digs on the grounds have revealed much about life in Jamaica in the early 1800s. New interactive exhibits and maps tell the story of Jamaica Village and its people in the early 1800s.

King Manor’s docent, Roy Fox, now well into his 80s, continues to handle tour duties in King Manor and has lived there for years! He has entertained two separate Forgotten NY tours. FNY first toured King Manor and nearby Prospect Cemetery in 2004, and that time NY Times reporter Robert Worth tagged along and filed an article.

Given an uptick in crime in recent years, the manor is fenced off from King Park (the largest in the immediate area) during off-hours.

Directly across Jamaica Avenue from King Manor is the former First Reformed Church of Jamaica, Jamaica Avenue and 153rd Street: the building has stood since 1859, with the congregation in existence since 1715. The original church was located at the present day Jamaica Avenue and 162nd Street, and moved to this location in 1833 and that church burned down in 1857. The First Reformed moved to Jamaica Estates and this building stood empty for much of the 1990s, after which it was reborn in 2008 as the Jamaica Performing Arts Center, now the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, after a $22 million renovation. Architect Sidney Young was a member of the congregation.

I always find it a bit difficult to photograph Grace Church as the sun shines on it only early in the day, long before my schedule permits me to get there, but it’s a bit better when it’s overcast. This high-steepled church on Jamaica Avenue off Parsons Boulevard dates to 1862, replacing an earlier edifice dating to 1822 that burned the year before. The parish itself goes back to 1702 and the surrounding churchyard to 1734.

Rufus King and his descendants were enthusiastic parishioners. His son, NY State Governor John King, contributed a marble baptismal font to the old church in 1847 and an organ to the new in 1862; later, the family provided an Oxford Bible, 4 prayer books and a bishop’s chair. Rufus King and his wife Mary are buried in the Grace churchyard.

Once again, recent conditions have prompted the cemetery fence to be locked much of the time, but I was able to enter in 2018 and photographed the churchyard as part of a Jamaica ancient cemetery post.

Jamaica, once a town in its own right in Queens County (which included Nassau County until it broke away in 1899) once had a magnificent town hall at the NE corner of Jamaica Avenue and Parsons Boulevard (which, along with Kissena Boulevard, was once the only route connecting Jamaica and Flushing). The town hall was built in 1869 and razed in 1941. It’s a McDonalds now. Photo from Greater Astoria Historical Society postcard collection, all of which are available for purchase in hi-res versions.

The Joseph P. Addabbo Federal Social Security Administration Building, completed in 1988 (the same year the nearby Archer Avenue subway line finally replaced the Jamaica Avenue El after 11 years). With its alternate brown shading, which reflects the sun nicely, it isn’t the “Ministry of Love” that some federal buildings occasionally resemble.

With U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Congressman Joseph P. Addabbo , Greater Jamaica Development Corporation assisted in the site selection, development coordination and urban design of the new home for the Social Security Administration’s Northeastern Program Service Center. The building, with 1 million square feet of floor space and employment of 3,000, opened in 1989. It serves New York State, New Jersey, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands—which comprise U.S. Region II. Greater Jamaica Development Corporation

Now is as good a time as any to mention that this stretch of Jamaica Avenue was shadowed by an elevated train until 1977 (it was razed the following year). It took 11 years, but subway service as far east of Parsons Boulevard was restored in a new underground tunnel that opened in December 1988.

Detour 160

I wanted to check on a pair of buildings on 160th St north of Jamaica Avenue that I thankfully found intact. The three story brick walkup building with the date of construction on the pediment, 1912, remains, as does the marvelous Art-Moderne streamlined building frontat 90-33 160th Street. It was built in 1934, when Jamaica was an entertainment hub, as La Casina, a nightclub when the country was emerging from Prohibition. Its two stepped pyramids flank a marquee-like overhang. For some years, it was the production office for Roxanne Swimsuits then home for the JBRC (Jamaica Business Resource Center), which aids small local businesses; and now a dental office.

These handsome guidepost signs are found on streets in downtown Jamaica.

On the left at 161-02 Jamaica Avenue is another branch of Jamaica Savings Bank . The present Beaux-Arts structure (Hough and Deuell, architects) went up in 1898. The building is marked by pilasters (half-columns on a building exterior) and two ornamental balconies. The ground floor is currently occupied by Filipino-based fast food franchise Jollibee. To its right was the 12-story Title Guarantee Building, constructed of yellow brick and limestone with a large arched entrance. It was torn down in 2016-2017 to make way for the present glass-fronted structure. The old building still shows up in Street View from years ago.

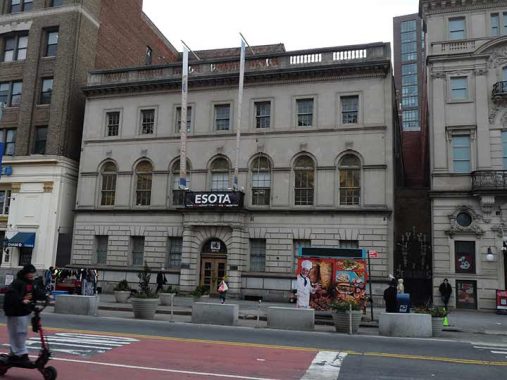

Next door at 161-04 is a dance academy, the Edge School of the Arts (ESOTA) also built in 1898 (A.S. Macgregor, Architect), a NYC Landmark, originally the Jamaica Register Building. The Italian Renaissance building is a somewhat somber companion for the more exuberant Jamaica Savings Bank on the right.

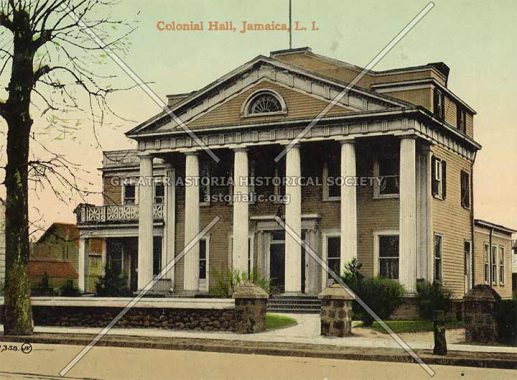

A classical, Doric-columned-fronted building at Jamaica Avenue and 161st that was razed in the 1920s was Colonial Hall, which hsoted a historical society as well as other functions.

Many neighborhoods now have new street clocks construted in a classic style, but this one at Jamaica Avenue and Union Hall Street is the real McCoy. It originally stood at 161-11 Jamaica Avenue and was likely built around 1900. It was restored and moved to its present location in 1989, directly across the street from the former site of Gertz, one of Jamaica’s largest department stores. It too was declared a NYC Landmark in 1981 (and so can’t be legally removed). The clock was manufactured by the The Self Winding Clock Company, a NYC based manufacturer of mechanical clocks from 1866-1970. Interestingly the most famous clock made by the company is the central brass clock in Grand central Terminal. The clock numbers are in the Hobo font, but I am uncertain if they are original.

One more handsome bank building, now harboring a Chase branch but formerly the Bank of the Manhattan Company. It sits on the corner of Jamaica Avenue and Union Hall Street. I had previously suspected that the name was retained because of the prevalence of trade unions in New York City, but I was incorrect. Instead, it preserves the name of the Union Hall Academy, opened in 1792, that occupied property on the street close to the Long Island Rail Road, in 1873 running on the surface at the present day Archer Avenue.

In 1791, the prestigious Union Hall Academy was built in Jamaica Township by residents of the three towns of Queens. An amount of $2,000 was pledged for the construction of the academy and it was an immediate educational success. Within four years after the original construction of the academy, it required expansion. At that time, in addition to a regular staff, there were five assistants to the principal as well as a library and research facilities. Some of the educators were well known such as Henry Onderdonk, the famous Long Island historian who taught at Union Hall between 1832 and 1865.

In 1841, a fire nearly destroyed the academy while Walt Whitman was on the staff. As early as 1816, it became so popular that a female school was added to the standard academy. However, the rise of the public school system provided too much competition for the fashionable educational establishment. Although other schools were being built such as the Maple Hall Institute, a private boarding school for boys, the Union Hall Academy was closed in 1873. — Kathleen Lonetto, Long Island Heritage

In 2012, Jamaica Avenue was given a set of “Triboro” lampposts, which the Department of Transportation designed in tribute to the lamps in use on the Triboto Bridge since its opening in 1936. They can be painted black or gray and appear on various routes in Queens and the Bronx, but Union Hall Street is the only place I see shorter “mini-me” versions.

The former Gertz Department Store formerly occupied the 5-story buff brick building on the south side of Jamaica Avenue between Union Hall Street and Guy Brewer Boulevard. The store, established by Benjamin Gertz as a stationery store in 1918, lasted until 1981 when it was consolidated under the Stern’s banner and later, the Macy’s flagship banner. The Gertz Mall occupied the basement for several years. The building was home to Conway, another discount department store, and presently fashion retailer Primark.

Gertz was the reason for my first excursion into Jamaica in 1968. My father purchased a wall unit for his tape recording equipment and bookshelves that remained with him until his death in 2003. Meanwhile, I acquired my first Hagstrom map of Brooklyn. We must have taken the J train on the Jamaica El to get there but I remember nothing of that.

Another pair of Jamaica Avenue edifices at 162nd Street. 161-11 has a pair of Greek gods, one of them Hermes with a winged cap, carved into the exterior.

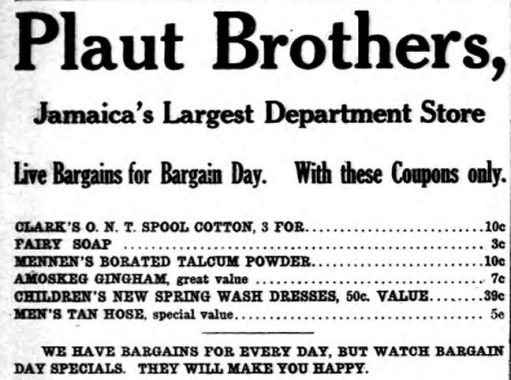

Simon, Louis and Moses Plaut opened their first department store in Newark, NJ in 1870, and had a branch in Jamaica in the early 20th Century. The Jamaica branch closed in 1935.

It must have galled both Gertz and J. Kurtz & Sons that two retailers with such similar names were close neighbors. The joyfully Art Deco building at the corner of Brewer Blvd. and Jamaica Avenue went up in 1931 (architects Allmendinger & Schlendorf –easy for them to say). It was designated a NYC Landmark in 1981. Kurtz distinguished itself from Gertz by specializing in furniture. Jacob Kurtz had founded the company in 1870, and the furniture store occupied the building until 1978, coinidentally the same year the Jamaica el closed (it was rerouted under Archer Avenue in 1988).

Guy R. Brewer Boulevard, which runs from Jamaica Avenue south to Rockaway Boulevard at Kennedy Airport, is one of eastern Queens’ oldest roads. On mid-19th Century maps it shows up as New York Avenue, became New York Boulevard by the 1920s, and was renamed along its entire length for 5-term State Assemblyman Brewer in 1982.

NYC naming conventions have changed. If the street was being renamed in 2025, it would have likely remained New York Boulevard, with second street signs for Guy R. Brewer added beside them.

Advertised as “Jamaica’s Largest Playhouse,” the Merrick Theatre had its grand opening on January 15th, 1921, with a two-day engagement of Paramount’s “Conrad in Quest of His Youth,” starring Thomas Meighan. The feature movies were presented with live prologues with “concert soloists and scenic effects.” Music for the entire program, including short subjects and a newsreel, was played by a symphony-sized orchestra, supplemented by a “magnificent” pipe organ. The Merrick had a complete change of show every Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. Its next feature attraction was Paramount’s “Life of the Party,” with Roscoe (Fatty) Arbuckle. cinematreasures

Stuart Building, 163-18 Jamaica Avenue, is a reminder of what office buildings looked like before the exteriors were made of metal and glass. I heard someone calling me after I snapped these photos, and it was one of the fellows milling around outside. I had to reassure him I wasn’t trying to photograph him; I wonder why he was concerned about that…

I am quite surprised that the First Presbyterian Church of Jamaica complex, 164th Street north of Jamaica Avenue, which includes the church, Magill Memorial Building and parish house, isn’t in the conversation of Queens’ most venerable church buildings. Jamaica’s Presbyterian congregation, founded in 1663, may be the oldest continuous one in the United States. The church is housed in three buildings on 164th, two of them very old.

The original congregation’s stone church stood from 1699 to 1813 at what is now Jamaica Avenue and Union Hall Street; during the Revolutionary War, the British commandeered it and imprisoned patriots there. In 1813, it was replaced with what is now the church sanctuary in a location at Jamaica Avenue and 163rd Street: it was placed on logs and pulled by mule to its present location in 1920. The First Presbyterian’s manse, or staff living quarters, was erected on Jamaica Avenue in 1834 and it was moved to a location just to the north of the sanctuary, well back from the street, that same year. In 1925, the Magill Memorial Building, a combined church, auditorium and library that also included a gym and bowling alleys(!) was built just north of the manse.

Decades before the Emancipation Proclamation, First Presbyterian had been a force in the struggle to eradicate slavery. It issued a proclamation in 1787 recommending that all people under the church’s care should work toward abolition; during the Civil War several members volunteered for duty, and the church hosted a regiment of Connecticut soldiers when their Long Island Rail Road train broke down in Jamaica.

Two relics in one at Jamaica and 165th Street. I don’t know what the corner tower originally was; but on the ground floor is a recently shuttered Boston Market. Originally Boston Chicken, its claim to fame was fresh cooked rotisserie chicken you could eat off the bone. I would buy a quarter breast, wing and two sides and set on it like a jackal till just the bones and some chicken fat remained; but bad management doomed the chain.

One of the boons of the Jamaica elevated being torn down in 1978 is that the Loew’s Valencia, at 165-11 Jamaica, can now be better viewed from this very busy stretch of the avenue. The theatre, designed by John Eberson in a Baroque Spanish style, opened in 1929. It has an intricately fashioned brick and terra cotta façade designed to be viewed from up close: the platforms of the Jamaica el were a few feet away. You really have to tarry for several minutes to take in all the cherub heads, seashells and other decorative elements. Unfortunately, it must not have been easy to examine it from anywhere except the elevated! It was one of five Loews “Wonder Theatres” that opened in 1929 and 1930, with the others being the Kings in Flatbush, the Paradise on Grand Concourse in the Bronx, the Jersey in Jersey City, and the Loews 175th on Broadway in Washington Heights.

The Valencia seated nearly 3,600, featured goldfish pools in the lobby, wrought iron railings, an auditorium resembling a festive Spanish garden, air conditioning as early as the 1950s, and pipe organ music until 1965. As with many Loews theatres, clouds and twinkling stars were projected across the dark theatre ceiling. The theatre presented elaborate stage shows until 1935, when they were replaced by double features. The Valencia’s first feature film presented was MGM’s “White Shadows in the South Seas,” a semi-documentary filmed on location in Tahiti; the last, in 1977, was Columbia’s“The Greatest,” the first Muhammad Ali biopic, starring Ali himself along with Ernest Borgnine and Robert Duvall.

A rival theatre not nearly as ornate, the Alden, stood directly across the street; no trace remains of it. The Valencia is now a church, the Tabernacle of Prayer, which thankfully has retained most of Eberson’s detail inside and out.

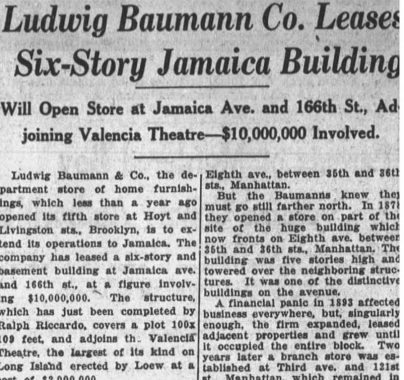

Adjoining the Valencia is this handsome 6-story building, stores at street level, emblazoned with the name Ludwig Baumann. Who was Baumann? The answer was surprisingly easy to discover.

The Baumann family was a furniture and home goods retailer active in the early to mid 20th Century. The newspaper clip from the Brooklyn Daily Times, 11/25/1928, is too big for me to screen capture, but you can read it here.

Before heading west along Liberty Avenue and Sutphin Blvd to Jamaica station, I wanted to see what’s going on with the aggressively Moderne 104th Army Field Artilley, constructed at Archer Avenue and 168th Street from 1933-1936. It’s relatively bereft of detailing, but how about those wrounght-iron “104”s on the railings!

Looking over the greater Queens community, Jamaica Armory was designed and built to be a fortress, providing training and protection during emergency responses. Construction began in 1928 when the Armory Board found the land and hired esteemed architect Charles B. Meyers whose Art Deco vision cost $1.5 million to build.

The Armory was completed in 1936, and the 104th Artillery became the first unit to occupy it. Soldiers shared the space with 138 horses, used to pull their 75-millimeter guns left over from World War I, and a harness repair shop. Other spaces included a gymnasium, offices, a lounge, locker rooms, recreation areas, a pistol range, and a bowling alley. OGS

As it happens, the NY State Office of General Services has a detailed account of its renovations, including some interior shots!

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

4/13/25

12 comments

The former Gertz Department Store was on the corner of Union Hall St. & Jamaica Avenue. Eventually the entire chain of stores closed. As part of an urban renewal scheme that ended a few careers, I believe, NY State leased space there (it was renamed Gertz Plaza). A few years later, the Social Security Administration built the red brick monstrosity on the corner of Jamaica Avenue & Parsons Blvd was just a few blocks west of Gertz Plaza. Since the New York State agency where I was employed serviced the Social Security Administration my colleagues & I were obliged to attend pointless meetings there occasionally. You have to enter this huge lobby & approach a raised reception desk. Protocol required that you not get too close to the reception desk; if you did, the angry, arrogant receptionists would scold you & demand official identification & the reason for your visit. Eventually, you were told where the meeting was. When the meeting began, another angry federal female was alternatively condescending & hostile. When the meeting ended, we were ushered out of there & I hoped that I never had to return. I was granted my wish. I retired in 2004. Almost exactly a year later, I was invited back to Gertz Plaza to attend a decommissioning party for Gertz Plaza. After many years of “decentralization,” the powers that be in Albany decided to “recentralize operations” & move back to lower Manhattan. By then, I was committed to relocating to Arizona. I brought along photos of the house I had just purchased near Queen Creek. I said my goodbyes to former colleagues & by July I had become a citizen of The Grand Canyon State. “Sic transit gloria mundi”

Great posting. You brought back lots of memories of the days I worked for LIRR at Sutphin and Archer, and when time permitted took a lunchtime stroll along Jamaica Ave. Many of those businesses are still there. The elevated structure remained unused atop Jamaica Ave. between Sutphin Blvd. and 121st St. for many years after the trains stopped running on that stretch in 1985 – it was not razed till the early 90s as I recall. I would occasionally stop for lunch at the Wendy’s (at Queens Blvd.) or the McDonald’s (at Parsons Blvd); good to see that both are still there.

If I may correct another item, there are four other new MTA subway stations that opened between 1950 and 2017. List is below. First one is on the Queens-Brooklyn border; other three are in Manhattan.

• 1956: Grant Ave A train (replaced an older elevated stop directly adjacent)

• 1967: Grand St B D trains

• 1968: 148-Lenox Ave. #3 train

• 1968: 57th St-6th Ave F train now; other routes prior to 20

Also, I did not count the stations inherited from the LIRR in Rockaway.

Thank you for noting that. I deliberately left those 13 ex-LIRR stations off the list of post-1950 new subway stations because they remained rail transit stations and never moved their locations. The station adjacent to Aqueduct Racetrack that only serves Manhattan-bound trains does qualify as a new station because it was added in 1959 when the racetrack re-opened after a rebuilding. Now, 66 years later, looks like the racetrack will close once Belmont Park re-opens, but the Resorts World Casino will likely remain, perhaps as a full service casino.

Also, the last sentence needs to be corrected to read “1968: 57th St-6th Ave F train now; other routes prior to 2001”. I inadvertently left off the last two digits – no doubt a senior moment.

And I left out still another one – 34 St. -Hudson Yards on the #7 – opened in September 2015. My bad once again!

!

The Magill Memorial Building. Home to Keglers for Christ, or the Holy Rollers.

Boston Market’s whole schtick was that their chicken was a healthier alternative to most other chicken joints because it wasn’t fried, however its monstrously high sodium content made these “healthy” claims meaningless.

As for C.H. Martin, within the past year it’s closed stores in New Jersey and Westchester, so I suspect that vintage website may never get updated.

I remember radio commercials for “Ludwig Bauman and Spears” in the 1960. I thought it was three partners: Ludwig, Bauman and Spears.

The mystery tower at the corner of 165th Street: it was a building that serviced the BMT Jamaica line (back in my day, it was the “15” train. It was connected by a bridge to the el towards the rear end of the 168th Street station. If you look at the second and third floors you will see bricked over portals. The upper one was an access bridge for subway employees. It did not reach the station platform. One had to walk across the track to access the ramp. The lower one was apparently for powerlines or some other conduits which ran under the bridge. See: https://www.nycsubway.org/perl/show?60474 and https://www.nycsubway.org/perl/show?43028

That corner building at Jamaica Avenue and 165th Street was an exit from the last stop of the Jamaica Avenue elevated. The tower contained the “tower” that controlled the interlocking west of the station.

I grew up in South Ozone Park, near Aqueduct race track. We often shopped in Jamaica — I remember taking the Q-41 Green Bus Lines route to a terminal on Jamaica that served several lines. I think it was on New York Avenue. In addition to Gertz there was a Macy’s department store and a May’s. The Macy’s store had parking space on the roof that I loved seeing on those rare occasions when my mother drove there rather than taking the bus. For my Confirmation in 6th grade, we went to the Robert Hall store in Jamaica (on Parsons Blvd maybe?) to get a suit jacket and slacks for my Confirmation. My mother let me pick what I wanted and I got a red blazer and black pants that I wore with a white shirt and black tie under my Confirmation gown. That would have been about 1966. Shopping in Jamaica went rapidly down hill not long after that as department stores in malls and a new Macy’s store a few miles away on Queens Blvd in Elmhurst drew customers away. Rising street crime in Jamaica also hurt. My mom also had a part time job at Gertz for a couple of years in the mid-60’s.

Why does the street clock you posted look different from the one from Google Streetview (a recent photo)?