SEVEN years after walking up Thompson Street, which runs north in Manhattan from Broome Street to Washington Squarein Soho and the Village, I walked north on its brother, Sullivan Street, one block east. I have to confess I do enjoy walking the ultra-urbanized streets full length more than the natural or pastoral ones in eastern Queens or Staten Island; to me urbanity is more engaging though I recognize the worth of pastoral. I choose to live in a garden apartment complex in Little Neck, far away from the hustle; I can get a LIRR train two blocks away into all the urbanity I can stand. I think I’ll do more of this, if the street in question is interesting enough for my infrastructural bends.

Streets in the area are named for Revolutionary War generals, in this case John Sullivan (1740-1795) who commanded in the Battles of Long Island, Trenton, Brandywine and Germantown. Controversially he also waged brutal war against Native American tribes who had supported the British in what is known as “Sullivan’s March.”

Beginning my trip at the Franklin Street station at Varick Street, a very interesting part of town architecturally as noted in FNY’s Finn Square page, you encounter Hook & Ladder 8 at North Moore and Varick, more popularly known as the “Ghostbusters firehouse” as this was the firehouse where the ambulance used by the spook-chasing comics in that 1980s 2-film series was headquartered. It is a functioning firehouse, though budget cuts had the 1903 masterpiece on the chopping block in May 2011. The next month, its continuation of service was announced.

Scouting NY revisits Ghostbusters scenes

I couldn’t resist stepping back a bit and getting the firehouse in the same shot as 56 Leonard, known to many as the Jenga Building. Few can afford an apartment in it.

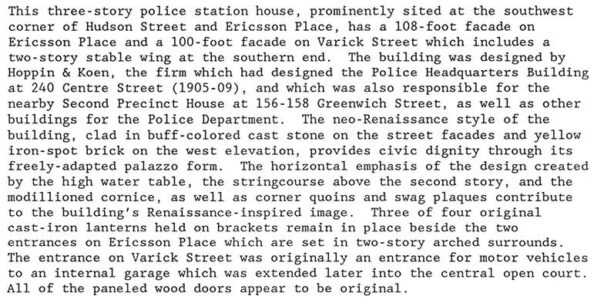

I seem to recall the 1912 NYPD 1st Precinct (originally 4th Precinct building (architects Hoppin & Koen) at Varick Street and Ericson Place still being used as a stable, but I could be wrong. From Landmarks Preservation Commission Tribeca West report:

Amazing how many shots I get, without trying, of stoplights on yellow. It’s only yellow for a second or so!

When in this part of Tribeca, I check on St. John’s Lane, an Belgian blocked alley that runs between Beach and Canal Streets west of 6th Avenue. Happy to see the block paving still there, and no obscuring scaffolds, at least in 2026. FNY wrote about it extensively in 2022, and can’t add any more than that here.

St. John’s Lane has a tiny tributary, York Street, that connects it to 6th Avenue. It is the only street in Manhattan named for its original British namesake, James, then Duke of York, the second son of King Charles I, who was in the royal family when Britain took control of New Netherland in 1664 and renamed it New York. (York Avenue on the east side was named for World War I hero Alvin C. York.) Until 1823, York Street was the eastern extension of Hubert Street, and until 1928 it extended through to West Broadway. The southern extension of 6th Avenue for the new IND subway that year cost York Street about 40 feet now occupied by the 6th Avenue roadbed. York Street, between 6th Avenue and St. John’s Lane north of Beach Street, is only 103 feet long, making it Manhattan’s second-shortest “one and done,” second only to Edgar Street. More “One and Done” in Lower Manhattan here.

Sullivan Street

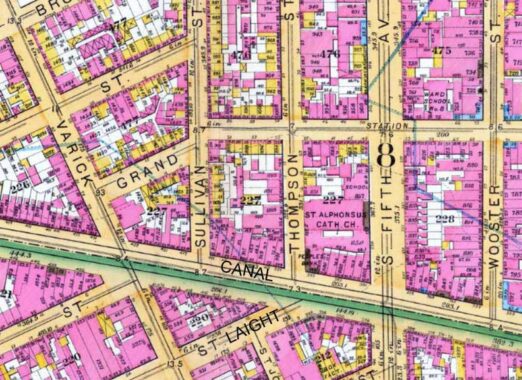

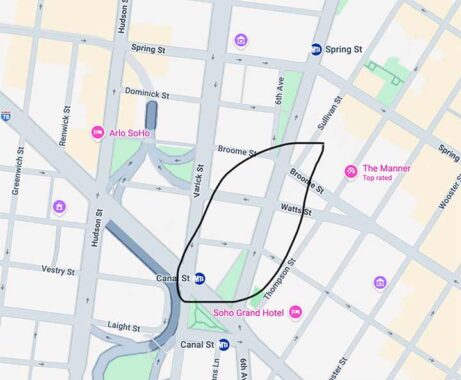

Through traffic used to extend south on Sullivan Street as far south as 6th Avenue until the mid-1920s, when 6th Avenue was bruited through the area atop the IND 6th-8th Avenue line built in that era. When this map was made, West Broadway was called South 5th Avenue; the route has also done time as Laurens Street.

The map of the area has been quite different since then, as Sullivan is now open to traffic only as far south as Broome Street. If you look carefully at the 2025 map, you see a thin line where Sullivan used to be, and that portion of Sullivan is still there, though it’s been open only to pedestrians for decades. The lot east of Varick and north of Canal has been empty for years, but the city is reconstructing the Canal Street Pumping Station in it.

I’ve been accused by some of not linking new styles of architecture: but I oppose new unimaginative architecture, like Fedders Specials or glassy facades. There are a number of buildings around town with oblong spaces architects have to fit buildings into, and one is #10 Sullivan at 6th Avenue and Broome. It was designed by architect Cary Tamarkin and built from 2014 to 2016. It replaced what was a car detailing shop and before that, a car wash. As a nod to the past it employs brick construction. It is the tallest building in SoHo. Interiors can be seen on StreetEasy.

It was possible to call that new tower #10 Sullivan because the developer wanted an easy to rememcer building number, and could do so because, as you recall, the lower two blocks of Sullivan were eliminated in the 1920s for the new IND subway and southern extension of 6th Avenue. #55 Sullivan, croner of Broome, conforms, as do the buildings north of it, to Sullivan Street’s original numbering. It’s another new building whose imaginative design I don’t mind with its large squarish windows and off white paneling. You can definitely see a contrast between residential architectural philosophies over two centuries apart. In 2009, the building replaced an auto repair shop which before that had been an empty lot.

Next door, #57 Sullivan Street was built from 1816-1817 (a third story was added in 1841) and is protected by its inclusion in the Sullivan-Thompson Historic District. It is also an individual landmark. As with most LPC reports, settle in not only for a history of the house, but a detailed description and history of the neighborhood.

Apologies, because of the sun position, I was unable to get complete shots of #83 and #85 Sullivan, further north on the block, without quite a bit of glare, so I concentrated on the ground floor. From the LPC report:

No. 85 Sullivan Street, and the adjacent 83 Sullivan Street, were built c. 1825 after a fire destroyed an earlier 1819 building on this site. The owner of 85 Sullivan Street, Drake Crane, was a carpenter. This three-story Federal row house features a Flemish-bond brick pattern with simple stone trim and six-over-six windows. The leaded transom over the entry door, the reeded molding, and the blocked corners of the molding surround are typical of the Federal

style.

#195 Spring Street, on the NW corner of Sullivan, is a Renaissance Revival building from 1902, built as a “new law” tenement permitting light and a new innovation, bathrooms with flush toilets. It’s been hard to make a restaurant on the ground floor succeed as both the Bombay Bread Bar and Bandone have failed in recent years.

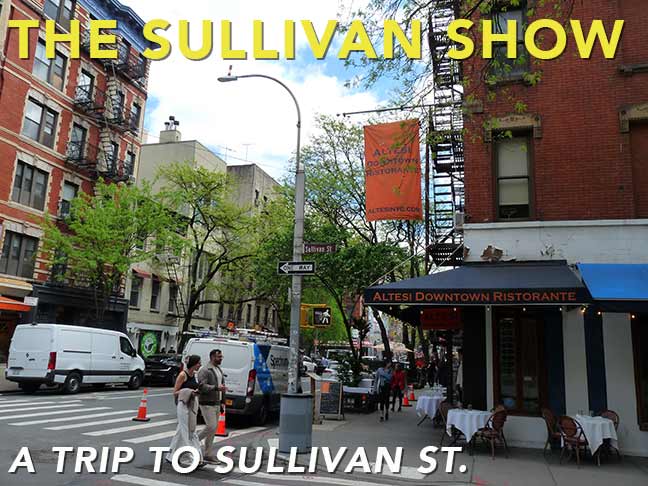

On the SE corner I noted the 1960s-era Donald Deskey lamp still hanging in there with its original design fire alarm indicator cone at the shaft apex. They were notoriously hard to keep attached. This is the edge of Little Italy and restaurants like Altesi Downtown, on the corner, are numerous.

It’s a good thing I got this photo of #114 (left) and #116 Sullivan, since the owners have requested that Google Street View place its Blur of Anonymity in front of it. Both are protected by the Landmarks Preservation Commission as part of the Sullivan-Thompson Historic District, and #116 has been awarded a Landmark all its own as early as 1970. #114 is a “three-story Federal row house was built in 1832 for Charles Starr, a prosperous bookbinder and real estate developer of seven houses in this former row on Sullivan Street. The building was constructed of Flemish-bond brick with brownstone trim. The building is known to have had a slate pitched roof prior to being raised from two to three stories with running bond brick in 1898.”

For its part, LPC says of #116:

“The glory of I16 Sullivan Street is the elaborate enframement of the front door within its simple round -arched masonry opening. The opening itself is flanked by plain brownstone pilasters, and by a flush-faced semi-circular band of brownstone defining the arch. The treatment of the side! ights was rare in its own time and is unique today. It is of great significance to New York domestic architecture. They are flanked by slender wood Ionic columns, backed by wood carved to resemble stone rustication. The columns in the corners are cut in half where they meet the masonry. The handsome entablature is broken back beyond the columns to form a recess over the door. The wood soffit of the arch, outside the fanlight, is paneled and trimmed by a carved molding. But it is the sidelights that are particularly worthy of note. Instead of the leaded glass treatment, typical of the time, each sidelight is divided into three superimposed oval sections. The ovals are formed by a richly carved wood enframement that simulates a cloth sash curtain drawn through a series of rings.”

Thus, LPC’s landmark award largely, er, hinges on its door treatment. Had I known this before researching it, I would have gotten a better shot of the door but rest assured it’s indeed impressive.

#107-109 Sullivan is a new law tenement (airier, with more light, etc) built for Michael Briganti by Horenburger & Straub in 1905. If you look carefully, the date of construction is in an entablature next to the 3rd floor windows.

#186 Prince Street at Sullivan is older than it looks, having originally been built in 1831 and attaining its present size and appearance after numerous alterations by 1869. The Dutch, a restaurant serving American fare, has been on the corner since at least the early 2010s. I have been attracted to Prince, Spring, and other SoHo east-west streets and have covered Prince on a number of occasions.

I was attracted to the SE corner building at Prince and Sullivan because of its awning sign. Anyone remember the SoHo News, a rival of sorts as a weekly counterculture/advocacy paper to the Village Voice? I do: it was well distributed. I wasn’t a regular reader but picked up a copy at a Bay Ridge newsstand around 1980 or so, when DEVO was on the cover. Their coverage of rock/R&B/pop was comparable to that of the VV and New York Rocker, one of whose editors was a college friend, Steve Graziano (RIP).

A brick building with an oval window will get my attention such as #138 Sullivan. LPC report: “This Greek Revival row house appears to have replaced a previous house on this lot in 1841-1842. The building was constructed of brick laid in running bond and features projecting brownstone sills and flush lintels. The house appears to have originally included a horse walk that provided access to the rear of the lot. A significant feature of the house is the oval window at the first story.” That window shows up in a 1940 tax photo, so it’s not a new addition.

Sullivan, like other N-S streets in SoHo, has a lively storefront scene. Atelier d’Emotion (“Emotion Workshop”), #137 Sullivan, sells handcrafted jewelry as well as objets d’art and perfumes. The building “was designed by architects Horenburger & Straub and built in 1904 for Isaac Grossman and Charles Michael, then president and secretary of the Peto Realty Co.”

St. Anthony of Padua Church, 155 Sullivan Street, was dedicated in 1888 and originally couldn’t be seen from Houston Street, as it was widened in the 1930s for the IND subway and properties on the south side of the street were condemned and torn down. The church, founded in 1859, was originally located a couple of doors south at #149 Sullivan before the present church went up. According to the New York City Chapter of The American Guild of Organists it was the first parish in the United States created to serve the growing number of Italian Catholic immigrants. Street View shows you better detail; once again because of sun angle, I was unable to get non-glary photos.

I discussed the MacDougal-Sullivan Gardens Historic District previously, on FNY’s MacDougal street page, so quoting here:

I had never been on the stretch of MacDougal between Houston and Bleecker, so I had never before seen this handsome grouping of attached brick buildings painted in tasteeful, unobtrusive colors. They are part of another Landmarks Preservation Commission designated historic district, MacDougal-Sullivan Gardens, which as you may expect extends a block east to the west side of Sullivan. The district is also one of NYC’s oldest, designated in 1967. The houses were constructed between 1844 and 1850, but had become run down within a few decades until they were purchased by William Sloane Coffin Senior of W&J Sloane Furniture, who developed them into what was, at the time, affordable housing; today, of course, space here is very expensive. Coffin Senior’s son, W.S. Coffin Jr., became a well known clergyman and peace activist.

If you’re from Flushing you know the clock-towered W&J Sloane Furniture Building on College Point Blvd., which became a Serval Zipper factory and is now a U-Haul center.

Once again, a contrast in residential building styles through the centuries, with #181 Sullivan, converted in 2006 by ADG Architecture and Design in the site of what was once the Sullivan Street Playhouse (longtime home of “The Fantasticks”) (earlier speakeasy Jimmy Kelly’s), and #179 Sullivan, built in 1834 and enlarged to its present size in 1879 on what was once called Varick Place. We’re sitting in the South Village Historic District, so how did #181 get such a radical alteration? The reason is simple. The historic district wasn’t awarded until 2013.

The huge, Beaux Arts Mills House No. 1 looks somewhat out of place on Bleecker Street, filling the south side of the block between Sullivan and Thompson Streets. As ornate as it is, it was built in 1892 to provide housing for the destitute. Ernest Flagg, who built Bay Ridge’s Flagg Court and a vast estate on Staten Island, was one of the architects. The apartments descended into decrepitude before the building was converted to more upscale housing in 1976.

Concert producer Art D’Lugoff opened the Village Gate in the Mills House in 1958 and it lasted until 1993. The musical “Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well…” premiered here in 1984. Over the years, the Village Gate has hosted concerts by Harry Belafonte, Pete Seeger, Dizzy Gillespie, Charles Mingus, Thelonius Monk, John Coltrane, and Aretha Franklin, and hosted “Macbird,” “One Mo’ Time” and “Scrambled Feet,” among others. The concert space is now used by a performance space/bar called Le Poisson Rouge. “Scrambled Feet” is the only stage show I ever did the Irish exit on, though I’m not really a musicals guy and didn’t “get” the satirizations.

I liked #214 Sullivan, between Bleecker and Washington Square South, built in 1900 as a paper box factory. Ancient factory buildings have been converted to handsome living spaces around town.

My eye wandered across the street to the handsome brick structure across the street with the Flemish gables, #209 Sullivan. The LPC report has this:

The 1891-92 building, formerly known as the Sullivan Street Industrial School, was one of a dozen structures built by the Children’s Aid Society during the 1880s and 1890s.The C.A.S. was founded by Charles Loring Brace, a Protestant minister, abolitionist, and member of a group of New York reformers. At the schools of the C.A.S., children learned woodworking, metalworking, sewing, cooking, and hygiene, in addition to traditional academic subjects (with an emphasis on civics and patriotism). This site was intended to serve the children of the heavily Italian neighborhood. By the 1930s, the schools began to focus instead on recreation and health, transferring academics to the New York City public school system. According to [longtime NY Times architecture columnist] Christopher Gray, all the C.A.S. structures of this era were similar in appearance, featuring red-brick facades, towers, and gables. The trade schools were typically free-standing with classrooms receiving light and air from all sides. Renowned architects Calvert Vaux & George Kent Radford were selected to plan for and design the various buildings (Vaux previously designed a country house for Brace in Dobbs Ferry, NY). The design of this Sullivan Street school, however, was apparently reworked prior to construction by Nicholas Gillesheimer, a partner of Vaux’s son Downing.

That’s indeed the same Calvert Vaux who co-designed Prospect and Central Parks, and many more parks, with Frederick Law Olmsted.

Vanderbilt Hall, between West 3rd Street, Washington Square South, MacDougal and Sullivan, which houses New York University’s law school, was completed in 1951 and looks older than that: it was built during an era when architects and developers still often strived to create contextual architecture that attempted to fit in with its neighbors. Nevertheless, during its development there was a considerable effort to derail it because several older buildings on West 4th and MacDougal were demolished to make way for it including former residences of authors and playwrights Willa Cather, Theodore Dreiser, and Eugene O’Neill, for which it was known as “Genius Row.”

While many buildings in New York are named Vanderbilt, most are named for transportation and real estate magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt. However, Vanderbilt Hall was named for New Jersey State Supreme Court Justice Arthur T. Vanderbilt.

This one, though, sticks out like a sore thumb. Speaking of noncontextual architecture, here’s #50 Washington Square South, NYU’s Hagop Kevorkian Center for Near Eastern Studies, the only building on Washington Square South east of Sullivan Street included in the South Village Historic District. That’s likely because it was co-designed by architecture giant Philip Johnson and completed in 1972, when Brutalism was in full “flower.” FNY readers know I’m not a fan of the genre, but it does have its proponents.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

1/29/26