In August I went on a “ramble” from the Canal Street A/C/E subway up through SoHo, Greenwich Village, and the East Side, getting as far as East 59th where I caught the N train to Queens. I’m intending to chop up this walk, for which I got 128 photos, into a number of shorter pages in keeping with my new policy of doing shorter Sunday feature pages—I found those 100+ photo descriptions were getting just a bit tedious.

My feature pages tend to be of two separate types: either I’ll describe disparate items all over town with the same theme, or I’ll just walk along one route and describe what I find there. I sort of prefer the former, but during the past few years, the latter has become more dominant, and I place it in STREET SCENES or WALKS, which are now heavily populated; I’ll just have to find more themes.

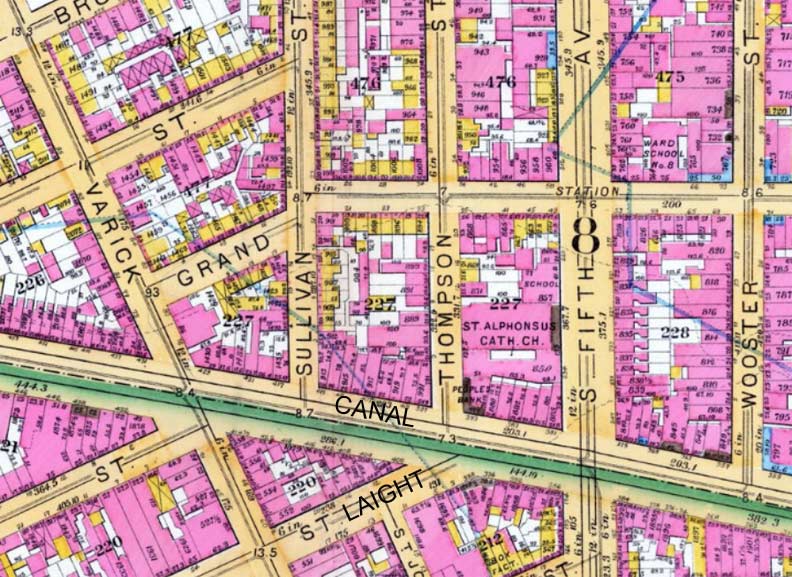

I got off the train at West Broadway and 6th Avenue, an intersection that didn’t exist in 1891 when this map was produced. 6th Avenue south of Carmine and Bleecker came into existence when the IND Subway was constructed in the late 1920s, with the original line opening in 1932. When this map was made, West Broadway was called South 5th Avenue; the route has also done time as Laurens Street. Thompson Street, where I wound up walking, began at Canal opposite Laight. Today, it’s one-way south and in the 1980s, traffic engineers eliminated its intersection with Canal, creating what’s essentially a U-turn onto traffic going north on 6th Avenue.

Both Sullivan and Thompson Streetsare named for Revolutionary War generals on the patriot side. Gen. William Thompson, an Irish immigrant who settled in Pennsylvania, led a patrol of sharpshooters to Massachusetts and repelled a British attack after the Battle of Bunker Hill. He got in trouble with Congress after he was captured by the British in Canada in 1776. After his return, he accused Thomas McKean, a Declaration of Independence signer, of hindering his release. Congress sided with McKean and censured Thompson.

The American Thread Company building, 260 West Broadway, NW corner of West Broadway and Beach Street, was constructed in 1896 as the Wool Exchange Building by an architect with one of my favorite names for any of the architects I find in my research, William Tubby. It was acquired by American Thread in 1907, which remained until 1964. 260 West Broadway converted to residential fairly early on by Tribeca or SoHo standards, in 1981. It has a rounded corner, a feature found much more frequently in the Bronx.

Here’s the story of one of the American Thread mills in Milo, Maine. A personal note–in this era when I have to find piecemeal copy editing and writing work, I miss the era of factory towns where it seemed that anyone who wanted one could get a job at one of these factories. Work was tedious, underpaid and in less than optimal conditions, but it was steady work, and many were eventually unionized. ATC was, and suffered from a number of strikes at various locations.

A bit of green on the east side of 6th Avenue south of Canal, interspersed with linden trees, is called “Yoya’s Park.” I’ve been unable to ferret out who Yoya is or was, so if you know, Comments are open.

For nearly 20 years (as of November 2018) Forgotten NY has been at its heart an infrastructure site, so here’s a pair of choice pieces at 6th and Canal: a “torch” fire alarm whose basic design was introduced in 1912, and a stanchion marking a nearby subway entrance/exit. The design was first used for the IND, though these are now used for all three (former) subway branches, IRT, BMT and IND. The red cap means it’s an exit only.

The south end of Thompson, where it jogs to 6th Avenue. A small parcel was used to place a couple of basketball courts; Henry Stern, former Parks Commissioner, playfully named it the Grand Canal Court since the north and south ends are on Canal and Grand Streets.

This is the back end, or service entrance, of James, the high rise hotel/restaurant at 6th and Grand. The James Hotel (architect: Eran Chen) replaced the Moondance Diner at 6th and Grand in 2009 . It is part of a chain of luxury hotels with franchises in Chicago and New York. Of interest is its rooftop pool and bar, “The Jimmy”:

[T]he roof bar [offers] some pretty stunning views stretching from river to river, as well as a great vantage point to watch the World Trade Center development in real time. [Eater]

Back in 2007, I celebrated the “victories” of saving both the Moondance and Victory Diner in Staten Island, but my end zone celebration was premature.

Maison Close, Thompson and Grand. I’ve been looking over those newly downloaded 1940s tax photos on the NYC Municipal Archives, as a lot of people have, and one thing that strikes me is the frequency of women’s hosiery and “foundations” stores in the business district. These days it all seems concentrated in Century 21 or Victoria’s Secret, as you don’t see so many storefronts dedicated to that anymore. There are some specialty shops, like this.

The “supertall” residential tower, 432 Park, pokes its nose above the skyline, looking north on Thompson Street. Though many decry the new domination of tall towers like this because many of their apartments are real estate investments for out-of-towners and remain unoccupied, they are popping up all over, from Hudson Yards to Long Island City, and the boom seems to be sustaining itself at least in the short run.

Both Watts and Broome Streets, despite being relatively narrow routes, are nonetheless traffic-choked as both funnel traffic to the New Jersey-bound Holland Tunnel. The buildings on Thompson between Watts and Broome serve as billboards for both huge advertisements (here featuring the CBS fall TV offering, a new version of FBI, as well as a canvas for street artists.

In the 1950s, traffic czar Robert Moses thought he had the perfect traffic solution: an elevated expressway along Broome, called the Lower Manhattan Expressway, that would link both the Williamsburg and Manhattan Bridges to the tunnel. That propsal was defeated, paving the way for Tribeca’s conversion from industrial/commercial to high-end residential, but the traffic problems have remained.

Perhaps the city could have built a traffic tunnel under Manhattan connecting the bridges and the Holland, but space in Manhattan is so tight it would still have necessitated a lot of real-estate teardowns and displacements.

After what seemed like an endless period of construction, the chi-chi luxury rental building 55 Thompson has arisen in its place, replacing the old Tunnel Garage, which stood for decades at Thompson and Broome. The contours of the new building, especially the rounded corners and paneled windows, are somewhat echoic of the old garage.

The Tunnel Garage’s old medallion showing a 1920-1921 Marmon Model 34 running through the Holland Tunnel has been saved, though not in an area open to the public. In the words of the online real estate website, Curbed, the medallion “hangs on the residents’ roof deck like a stuffed moose head in a hunter’s cabin.”

Brilliantly-colored street art has flourished in the last couple of years as never before including this piece on Thompson between Broome and Watts.

Across the street, Watts St. meets Broome at a triangle park. It’s another result of latter-day street engineering, as prior to 1905 or thereabouts, Watts ended its eastern progress at Sullivan, but then it was extended to meet Broome just west of W. Broadway, creating the triangle.

I first started visiting this part of Soho in 1981, when my friend Steve Graziano, who managed such bands as Certain General and Band of Outsiders—both still playing today—and who passed away in 2005, was living nearby on Thompson St. In the triangle formed by Thompson, Broome and Watts, I saw what seemed to be a whole pile of metallic junk strewn on what was then a plain concrete surface. It’s come a long way since, as Robert S. Bolles’ (also known as Bob Steel) creations now reside in a landscaped garden stuck between three streets that are absolutely jammed with cars honking their horns at 150 db.

40 Watts St. could stand up to the Tunnel Garage in original grandeur. It was constructed in 1928 as a power company substation, but was apparently meant to echo the garage’s appearance. Like the old garage, it’s now used as a big billboard ad holder. A succession of bars and clubs have held down the ground floor.

A look east from the eastern end of the triangle park to West Broadway and Broome. Kenn’s Broome Street Bar has operated under a number of names here since the 1850s, in a building that goes back to the 1820s. It has been a haven for truckers and later, SoHo artists like Claes Oldenberg, Willem de Kooning, and Keith Haring. I’ve never been in—perhaps if I do a Tribeca/SoHo tour in 2019.

Real estate site 6 Sq Ft makes the argument that 514 Broome, off Thompson, is the only freestanding residence in SoHo. Whether that’s true or not, the site shows off some dazzling interiors while the building was for sale in 2015 for nearly $7M.

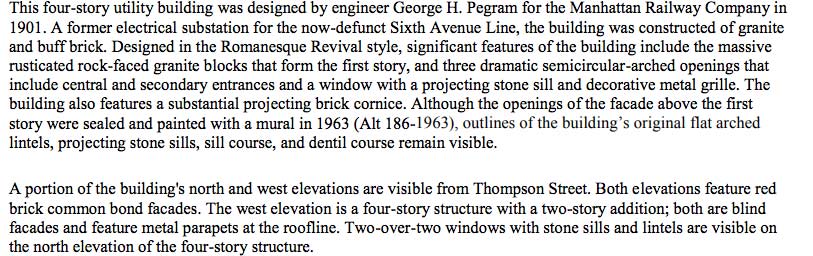

I’ve aways been curious about this massive building at 175 Spring Street, just east of Thompson, and it turns out it’s one of the last remnants of the old 6th Avenue El, eliminated in 1938. From the Sullivan-Thompson NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission report:

The corner building, 86 Thompson, goes back to 1878.

Iconic German designer Karl Lagerfeld’s offerings are available at 96 Thompson. I also found him on a Queensboro Bridge exit ramp in Hunter’s Point, Queens, in July 2018.

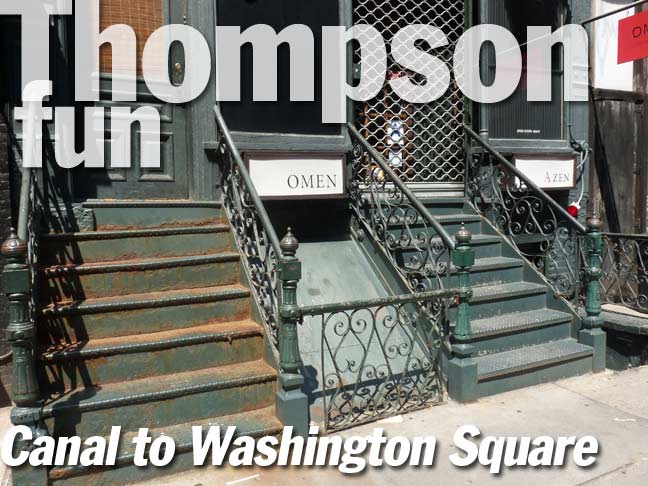

113 Thompson, between Spring and Price, looks relatively little changed from when it was last renovated in 1901—though the building itself is much older, dating to the early 1840s. The metalwork on the ground floor dates to its 1918 incarnation as a factory. Currently it is the home of Japanese restaurant Omen Azen.

Chalked-in hearts on Thompson, possibly left over from a street fair.

Looks can be deceiving. Though this rectory at 147 Thompson for the nearby St. Anthony of Padua Church was built in 1914, it was completely remodeled in 1949, and bears that date on its cornerstone.

This is the magnificent 1886 friary for St. Anthony of Padua Roman Catholic Church, which fronts a block away at Sullivan Street at West Houston. It is of French Second Empire design; the architect was Britisher Arthur Crooks. A friar is a male member of a religious order; they’re called Brothers, and they differ from monks in that they are not cloistered, but interact with society.

Arturo’s Pizza at West Houston and Thompson was founded by Arturo Giunta in 1957 (the year that I was founded). Some rate the fare among the best in the city.

[Arturo’s] retains a raffish, scruffy charm that most of Greenwich Village lost long ago. It’s not just that the ceilings are tin and battered; that there are countless signed celebrity head shots on the walls; that bad oil paintings by amateur artist Arturo occupy the spaces not taken up by actor photos; that nobody can remember who painted the large fading murals, or what scene they’re supposed to depict; or that they used to perform plays in the back room in the ’70s. It’s more that, in very Old School Villagey style, Arturo’s still has live jazz music every day. It’s that the staff all seem to be ancient or bohemian or somebody’s underperforming relative. This is a classic New York staff, and they’re part of the place the way ivy’s part of a wall. The young waitress wears cat-eye glasses and a leather skirt. The manager looks like a librarian at an alternative-reading library. When the genial greeter in the baseball cap introduced me to the owner, she sized me up and said, “Who is this?” A customer, the greeter said. “Oh, mystery man!” [Brooks of Sheffield, Eater]

A palimpsest neon sign. Carbone Liquor’s letters were superimposed on a much oder neon sign for a former restaurant at the same premises.

Now edging into Greenwich Village, Thompson Street becomes more overtly commercial but still retains a number of singular establishments. My guess was that this was a restaurant featuring pork but the NY Times reports that pig is hardly the only thing on the menu. I just liked the straightforward gray and white sign.

Reviews for Generation Records, 210 Thompson between Bleecker and West 3rd, are mixed, but it’s one of the few pure record/CD stores left. Among my old favorites were Tower, Broadway and East 4th; Sounds, 20 St. Mark’s; Venus, East 8th. Oddly Bleecker Bob’s was not one of my haunts though other shops on Bleecker were. I always found Goody’s overpriced. At least one Sunday per month I would go record hunting and go home to Bay Ridge with stacks of wax, nearly 7 or 8 per trip as LP’s were still held to $7.99 or under.

I have many regrets. One of them is that I have not learned how to play chess. Though the game is anything but simple, I have always been attracted to the purity of the black and white board and pieces in different shapes. Chess is essentially war played out in miniature–some of the greatest generals have been chess masters as well.

It turns out that the area south of Washington Square has been a “chess row” for several decades, with shops selling chessboards and pieces. There is a game or several always going on in Washington or Union Squares and you can try your luck with the players you find there, but watch your back, these guys are hustlers just as much as the three card monte guys, and they have more advantage than your average casino.

Chess Forum, Thompson between Bleecker and West 3rd, is the lone surviving store dedicated to chess.

For well over a century the campanile of Judson Memorial Church, at Washington Square South and LaGuardia Place has dominated the view south from Washington Square. The church is also the work of architect Stanford White, and features stained glass by John LaFarge and sculpture by Augustus St. Gaudens, and went up in 1896; it was designated a NYC landmark in 1966. Adoniram Judson was the first American baptist missionary in Asia, working primarily in Burma. Like a lot of property in the area, most of the complex now belongs to New York University.

Over the years, befitting its location in the heart of Greenwich Village, the church has been the epicenter for both the arts and ‘social consciousness.’

These lamps, which use electric LED bulbs but imitate gaslamps, have dominated Washington Square Park for the last decade or so.

They replaced these L-shaped lamps with square shafts, which dominated the park beginning in the 1970s. this is probably one of the last remaining ones.

Looking north past the fountain (which was installed in 1872, replacing an earlier one from 1852), to Stanford White’s memorial George Washington Arch (1892) and One Fifth Avenue, a hotel built in 1926, with a restaurant called One Fifth on the ground floor I would frequent in the 1980s.

If roads czar Robert Moses had got his wish, the circle around the fountain, which was once used to turn 5th Avenue buses and was open to motor traffic when the Queen of Avenues was one-way, and the fountain would be moved to make way for a connector road between 5th Avenue and LaGuardia Place. Locals fought Moses tooth and nail (as they did against his proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway on Broome Street) and after a lot of vitriol, the Master Builder backed down. However, the fountain was moved anyway between 2007-2011, but not without a hue and cry I mostly failed to understand.

White, therefore, has monuments at both the north and south ends of the park, the Judson Memorial Church and the arch. When ground was being cleared for the arch, human remains were found underground, a reminder that Washington Square had once beena potter’s field. When further renovations were done from 2007-2012, a tombstone was found.

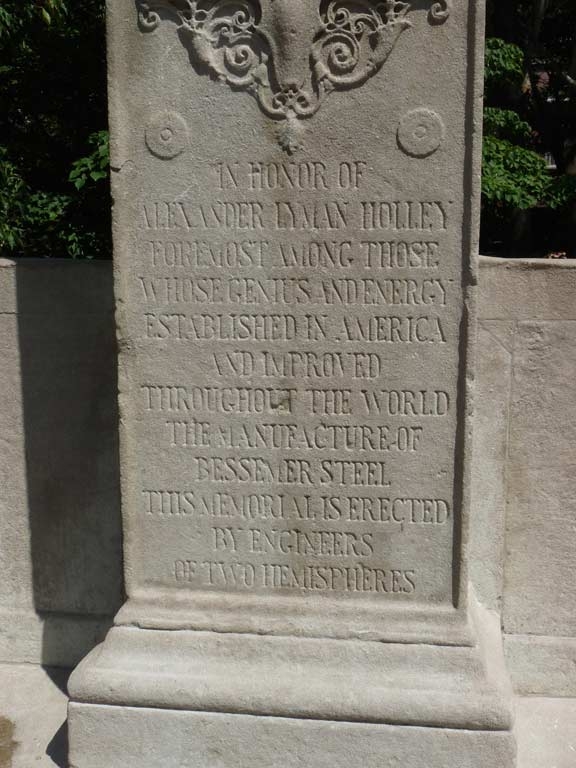

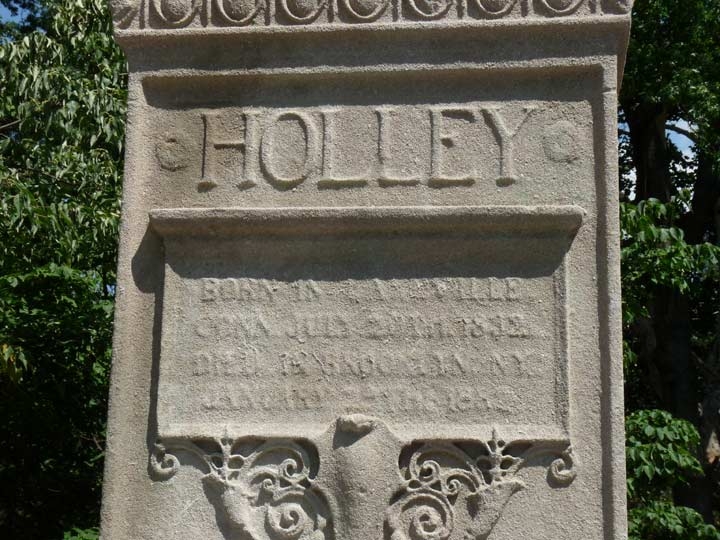

I don’t know if a present-day industrialist would rate a memorial in Washington Square today, but Alexander Lyman Holley is here, and his 1889 bust by John Quincy Adams Ward isn’t going anywhere.

While traveling in Europe, he observed the Bessemer process for making steel and realized its practicality and efficiency. When he returned to the states, he convinced his employer to buy the American patents for it and he became the foremost designer of steel works in the country.

The monument was dedicated Oct. 2, 1890, a gift from three professional engineering societies, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers and the American Society of Civil Engineers, though money was raised from related professional groups around the world.

Not everyone was thrilled by the gesture. Many critics, including the editorial boards of several New York newspapers, complained that Holley was hardly a household name. Dianne Durante, author of “Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan,” records the NY Times’s indignant (and rather tortured) thesis from April 24, 1890: “The time is coming … when sites for statues in the Park will be too scarce to be assigned to effigies from which the general public will derive its first knowledge that the originals of them have existed.” NYC Statues

After fighting in South American wars of liberation, using what today would be called guerrilla tactics, Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882) organized and led insurgencies leading to conquests of Sicily and Naples which ultimately produced the unification of Italy in 1860. Abraham Lincoln offered Garibaldi a command in the Civil War, but Garibaldi asked for the post of commander-in-chief, which Lincoln was unwilling to consent.

Garibaldi resided in a house on Rosebank, Staten Island’s Tompkins Avenue from 1851-53 with his friend, Antonio Meucci, who invented the telephone before Alexander Graham Bell received his own patent for it. The house is now used as a museum.

From the Washington Square Arch, 5th Avenue proceeds in nearly a straight line north to Mount Morris (Marcus Garvey) Park at 120th Street.

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

11/25/18

2 comments

Did you happen to notice the older looking gates beside 40 Watts st on your walk? Do you happen to know if there is any history to them? They look incredibly out of place there.

My best friend lived at 211 Thompson all through the 1980s, starting as a grad student at NYU. There was a musty, exotic little store down the street that sold the most incredible-smelling glycerine soap. We loved the Rain and China Rain scents the best. Neither one of us can remember the name of that store! Any idea? Thanks in advance.