HOPING I’ll be able to return to lengthy walks sometime soon but fortunately, I do have a backlog of photos such as the 133 I got during a June 2024 walk from Brooklyn Heights to Prospect Park, primarily using Hicks, Columbia, Union, Sackett Streets and Berkeley Place. As with the previous post from Sunset Park to Maspeth, I’ll need to divide things among multiple posts. As with all my forays, I seek out bits of infrastructure and architecture I find interesting, as I hope that’s what you’re seeking as well.

GOOGLE MAP: BROOKLYN HEIGHTS TO PROSPECT PARK

Initially I’ll reference the work of architectural historian Clay Lancaster (1917-2001), who I know little about but his books “Old Brooklyn Heights: New York’s First Suburb” (1979) and “Prospect Park Handbook” (1967) were influential on Forgotten New York. A girlfriend I had at school gifted me for my birthday in 1982 with “Old Brooklyn Heights,” so, even then, I must have been going on about infrastructure. (I haven’t talked to her in decades; she is married and living in western NJ, and I hope and assume she is doing well.)

Since Brooklyn Heights is so brownstone-heavy I’m attracted to its remaining frame or brick buildings, such as #166 (left) and 164 Hicks Street, south of Clark Street. These Greek Revival buildings have retained their pilastered (half-columned) doorways and were built as early as 1840. Both were re-sided in spite of the region’s Landmarks designation in 1965.

Skipping south to Remsen street, where my alma mater St. Francis College was located until a few years ago, here’s #58 Remsen on the corner, one of a trio of brick row houses built in 1844. The mansard roof on #58 was likely added in the 1870s or 1880s as French Second Empire slanted roofs were very popular in that era. A pair of chiseled streets signs above the first floor date back to the era before street signs were common.

Grace Court Alley proceeds east to a dead end from the east side of Hicks Street south of Remsen. It is not exactly on the same line as Grace Court and the two may have developed independently of each other. I’m not sure when it acquired its awkward name, but there are a couple of other Brooklyn streets that follow the same pattern: Shore Road Lane, on Shore Road just south of Ft. Hamilton High School in Bay Ridge, and Shore Road Drive, built in about 1940 to connect 4th Avenue and 66th Street with the Belt Parkway (it does not intersect Shore Road, and I’m not sure if it ever did).

Like Manhattan’s Washington Mews and Macdougal Alley, it was a lane that originally held stables serving buildings on parallelling streets. Long ago the stables were converted into carriage houses, and today fetch prices unimaginable to the artisans who built them in the 19th Century. Most of Grace Court Alley’s north side and all of its south side are given over to these carriage houses.

Oddly the term “mews” originally had nothing to do with horses:

The term mews is plural in form but singular in construction. It arose from “mews” in the sense of a building where birds used for falconry are kept, which in turn comes from birds’ cyclical loss of feathers known as ‘mewing’ or moulting.

|

Though the term originated in London, its use has spread to parts of Canada, Australia and the United States (see, for example, Washington Mews in Greenwich Village, New York City).

|

From 1377 onwards the king’s falconry birds were kept in the King’s Mews at Charing Cross. The name remained when it became the royal stables starting in 1537 during the reign of King Henry VIII. It was demolished in the early 19th century and Trafalgar Square was built on the site. The present Royal Mews was then built in the grounds of Buckingham Palace. The stables of St James’s Palace, which occupied the site where Lancaster House was later built, were also referred to as the “Royal Mews” on occasion, including on John Rocque’s 1740s map of London. wikipedia

The AIA Guide to NYC (White and Leadon, 2010) makes note of the “crisp, contrasting brownstone quoins” on #2 and 4 on the south side of the alley. Even for stables, great care was given to detail and workmanship in the 19th Century. Note that Grace Court Alley has no sidewalks and owners walk in directly from the roadbed.

I always check on the alley’s wall bracket lapm. In my memory it has carried an incandescent, sodium and LED lamp fixture.

Here’s a detailed look at Grace Court and Grace Court Alley.

Grace Court is named for Grace Episcopal Church on the southwest corner of the court and Hicks Street. There’s a number of historic Grace Churches around town, from the one at the bend of Broadway and West 10th Street in Greenwich Village (1846, James Renwick) in downtown Jamaica, Queens (1862; also accompanied by a Grace Court) Canarsie, Brooklyn (now called the Church of the Rock, but the tallest steeple in the neighborhood) and City Island, Bronx (1867). All are, or were, Episcopalian or Anglican, as preferred these days.

Brooklyn Heights’ Grace Church was the work of Richard Upjohn and was completed in 1849, a few years after his NYC masterwork, Trinity Church at Broadway and Wall Street, and it resembles that building’s British Gothic Revival style. (Trinity, Grace and what was originally the Church of the Pilgrims at nearby Remsen and Henry Streets have all held up well among Upjohn’s churches; but his St. Saviour’s Church in Maspeth, Queens is a sad story.) It was actually built so Brooklyn Episcopalians wouldn’t have to ferry over to the Renwick church in Manhattan.

Built of red-gray New Jersey sandstone, the building has many vertical projections in the form of pinnacles and finials, gables and parapets. An enormous and beautiful traceried window dominates the eastern wall behind the altar. The alabaster altar, stained glass windows, mosaic tile floors and stone columns create an interior of rich design. Grace is set among large trees, with a charming courtyard, giving the impression of an English parish church within the city. Grace Church

Brooklyn Church Uncovers a Long-Hidden Celestial Scene [New York Times]

Grace Church [American Guild of Organists]

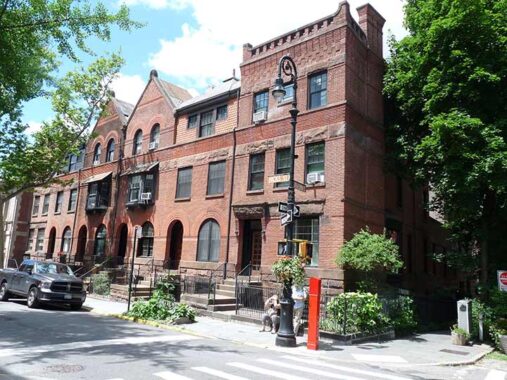

Now we’re talking..this grouping of attached brick houses at #262-268 Hicks and Joralemon Street are up my alley, architecturally, if not my affordability. Oddly Lancaster is silent about them in his book, but my guess is that the Queen Anne-style buildings went up in the 1880s. In 2025 a one bedroom in #262 sold for $465,252, but with an $874 maintenance, less than my own in Little Neck.

According to the reliable Suzanne Spellen in Brownstoner, the Renaissance Revival Engine 224 at #274 Hicks was built in 1903 by the firm of Adams & Warren which actually makes it one of the newer buildings in the immediate area. It has Beaux Arts touches that weren’t yet fashionable on the older structures.

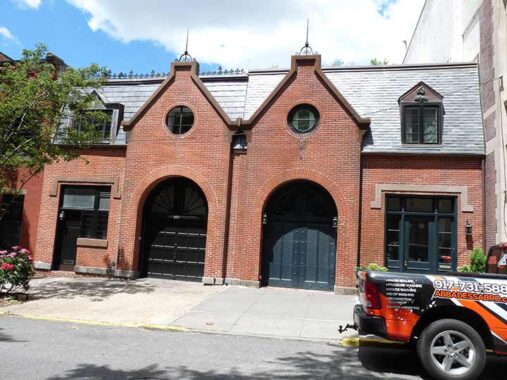

Next door to the firehouse are a pair of brick Queen Anne carriage houses, #276 and 278 Hicks. What’s amazing to me about carriage houses is that they sell for fantastical figures in the 202s, but when built in the 1880s they were where horses were stabled, hayed and fed.

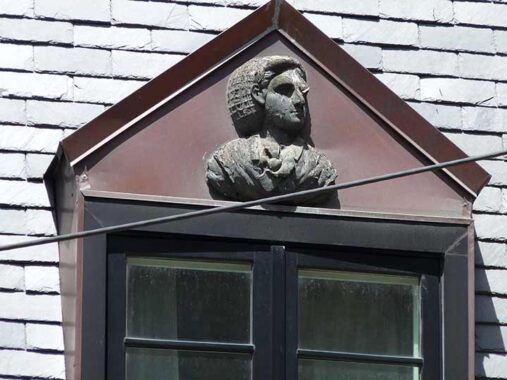

Despite this prosaic use, in the 1880s detail wasn’t to be denied and the figure of a woman was placed on one of the dormers. The owner, or wife of the owner, perhaps.

Lancaster apparently didn’t care for carriage houses, as he is silent about #291 and 293 Hicks. He is quiet about #295 on the right, as well he should be, as it was built in 2024 in a remarkable imitation of its two predecessors to the north! If you had an extra $26M lying around you could have jumped on top of it.

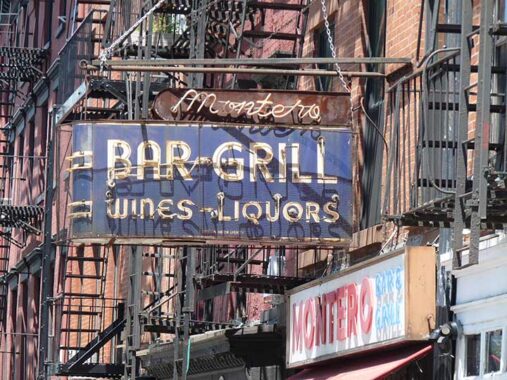

Montero Bar and Grill, 73 Atlantic, has been part of the Atlantic Avenue scene since 1940. It relocated to 73 Atlantic from 56 in 1947 after the BQE condemned its first locale.

Every single inch of Montero Bar and Grill is crowded with stuff, mostly gifts that sailors and seamen brought the original owner, Joseph Montero, since he opened here in 1947. Some of it dates from even earlier, when his bar was across the street. Thirty-four ship models, dozens of shipping prints and a veritable family album of the Montero family’s lives are just a sample of the items hanging from the walls and packing the alcoves. But this is not a museum: it is a living, breathing bar. It has remained raffish and even a little intimidating as the neighborhood around it has grown wealthy and precious. Wendell Jamieson, “A Raffish Reminder, Landlubbers, of Saltier Days,” NYTimes, May 9, 2003

Co-founder Pilar Montero died in 2012.

A bit of past nomenclature can be seen at the NW corner building, 75 Atlantic, at Hicks Street near Montero’s: Atlantic Avenue was Atlantic Street. In the 1700s, the avenue was a path to Ralph Patchen’s farm at the East River waterfront (Ralph and Patchen are now Bedford-Stuyvesant avenues); by 1816 it had become District Street; by 1855, Atlantic Street. In a year either side of 1870, it had become Atlantic Avenue–by then Long Island Rail Road tracks extended east to Jamaica and the right-of-way assumed its name. So, this building is quite old; it goes back to at least 1870.

I was attracted to Montero’s ancient neon sidewalk sign, manufactured by Corvin Neon Sign Co. The neon still works and lights up red at night.

I can’t resist getting a photo of the craftsmanship of a curved storefront window, like I. Weiss and Sons Plumbing at #71 Atlantic Avenue exhibits. The window looked about the same in 1940 when the location was a drugstore.

One of NYC’s remaining iron trolley poles remains at Atlantic Avenue and a Brooklyn Queens Expressway off ramp, Exit 27. It one supported wires providing electric power to surface lines #15 (Crosstown) and #28 (to Erie Basin in Red Hook). Trolley service ended here in 1951. Currently the pole conveniently carries “Do Not Enter” and One Way signage.

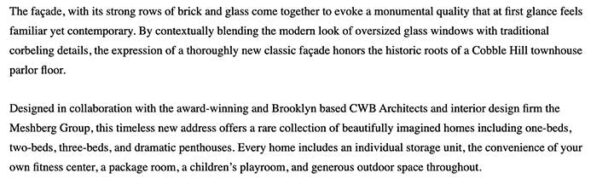

Many who read Forgotten NY think I have nothing good to say about new architecture. Nonsense. Here’s a new building I like, at #78 Amity Street, on the corner of Hicks. It employs classic brickwork and large, rectangular windows to hark back to a classic brick building esthetic. Though the Cobble Hill House, as it’s called, doesn’t permit copying the text on its website (I won’t link to it as this is not a plug for the condo), there’s more than one way to skin a cat.

The building, constructed in 2018, brings back the old practice of showing the cross streets on the building corner. The nly drawback is the thrumming traffic of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, in an open cut on Hicks.

Amity Street (the name means “peace”) runs three blocks between Court and Hicks Streets a block south of Pacific. Possibly its greatest claim to fame is #197, where Jennie Jerome was born. Who was Jennie Jerome? Her father was financier Leonard Jerome, who organized the American Jockey Club and built the Jerome Park Racetrack in Kingsbridge Heights in the Bronx in 1865. Jennie Jerome worked as a magazine editor in an age when few “respectable” women worked and wedded three times; her first marriage, to Lord Randolph Spencer Churchill in 1874, whom she met on a visit to Britain, produced Winston Churchill, who became the wartime Prime Minister of England, and his brother John.

Cobble Hill is named for Cobble Hill Fort in the U.S. Revolutionary era, from where George Washington monitored troop movements in the unsuccessful Battle of Brooklyn campaign. The hill has since been leveled. “Cobbles” were smooth rocks used for ship ballast and street paving.

A relatively new quintet of brick apartment buildings, #112-120 Congress Street at Hicks, were constructed in 2014. They strive to adhere to an older brick walkup esthetic but don’t quite succeed especially with the wraparound bay at the corner. They were built within the Cobble Hill Historic District, one of NYC’s oldest (1969).

Forgive me, there are better photo ops for Van Voorhees Playground, Congress Street between Hicks and Columbia Streets. The name sounded familiar:

This park honors Tracy S. Voorhees (1890-1974), an attorney and decorated World War II veteran, and his family’s early contributions to the City.

The Van Voorhees family traces its lineage to Steven Coerten Van Voorhees who settled in Brooklyn in the mid-17th century. He established himself in the neighborhood of Flatlands, became a magistrate, an elder in the Dutch Reformed Church, and the head of a formidable clan. His ten children bore 20 grandchildren. The grandchildren amassed 85 children themselves, among them Tracy Voorhees, to carry on the family name. The “Van” was eventually dropped from the name. [NYC Parks]

It’s quite possible Voorhies Avenue in Sheepshead Bay was named for the family. It’s one block south of Avenue Z (they were fresh out of letters).

Before the early 1950s, Hicks Street was the same one-lane street its parallel companions Henry and Columbia Streets are, but it was selected for the route of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway by Robert Moses, who put it in a trench that separated one side of Cobble Hill from the other. It’s bridged only by Congress, Kane, Union and Sackett Streets until joining the Gowanus Expressway at the Brooklyn-Battery (Hugh Carey) Tunnel. Hicks runs in one-way sections alongside the BQE.

Columbia Street, Columbia, South Carolina, Columbia University, the country of Colombia, the District of Columbia, the military hymn “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean” and many other place names all derive from Christopher Columbus, whose name in Italian, Cristoforo Colombo, can be said to translate to “Christ-bearer Dove” after the Latin has been turned to English. Columbus, it is said, rarely wrote anything in Italian, as he learned to read and write in Portugal.

Columbia Street begins its run at Atlantic Avenue just west of the Brooklyn Queens Expressway overpass and Furman Street. At one time, Columbia Street continued northeast past Atlantic Avenue as Columbia Place. The BQE makes a bend toward the waterfront here (in the 1950s, Brooklyn Heights residents petitioned highway engineer Robert Moses to swerve the road to the industrial waterfront to spare their buildings) and Columbia Place between Atlantic Avenue and State Street was then eliminated. The BQE also took out Emmett Street, which ran between Atlantic Avenue and Amity Street east of Columbia.

Meanwhile, yet another Columbia, Columbia Heights, can be found in Brooklyn Heights, overlooking a steep cliff that looks down on the East River, Furman Street, and by the 1950s, the BQE.

The stretch of Columbia Street in Cobble Hill hosts one of the final vestiges of the Brooklyn working waterfront as the Port Authority Brooklyn Marine Terminal can be found here.

The Act One Thai restaurant at Columbia and Kane Streets has closed since I got this photo in June 2024, but I took note of its side wall mural. Along this stretch of Columbia Street I took note of some interesting artwork and signage.

Until 1928 Kane Street was known as Harrison Street, but the name was changed to honor election commissioner, alderman (today that would be a City Councilman) and police sergeant James Kane (1839-1926). There was a different philosophy then about renaming streets. Until the 1980s or so, the name was changed, and that was that, but following the 1980s a street was not so much renamed as subtitled., i.e. both names would appear. I think the last time street names were just changed, with the old names wiped out and the new ones replacing them, were in the 1970s when 7th Avenue and 8th Avenues became Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, Jr., and Frederick Douglass Boulevards.

One recent exception is South Road in Jamaica renamed as Tuskegee Airmen Way, for the African American WWII military aviators and support personnel.

This stretch of Columbia Street takes on a distinct bohemian vibe. At #119 is Ruby’s House of Crystals. I’ll let Mindtrip explain what is available here:

Ruby’s House of Crystals is a charming store located in Brooklyn, specializing in a variety of crystals, gemstones, and holistic healing items. Visitors can explore a diverse selection of products, from raw crystals to polished specimens, along with handmade jewelry and spiritual tools. The shop fosters a welcoming atmosphere, often hosting workshops and events that focus on crystal healing and mindfulness practices. Its unique offerings make it a treasured spot for both locals and travelers.

My attitude about this kind of thing is “you do you.”

Next door, the Hop Shop has an interesting sidewalk shingle sign. From the name I thought it was a cannabis dealer, but instead it’s a craft beer bar.

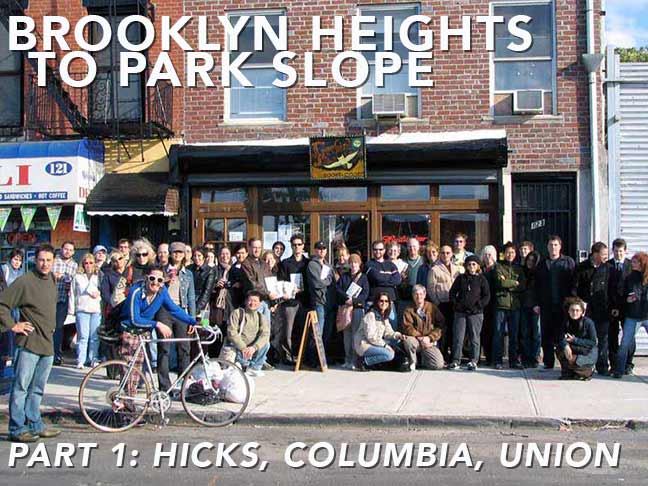

I remember Freebird Books, a venerable used bookstore that also sells new titles, at #123 Columbia very fondly, as it hosted the very first book event for Forgotten NY the Book, arranged by my publisher Harper Collins, in October 2006. The crisp clear weather couldn’t be beat as over 50, including some lifelong friends, turned up. After the book signing I led a short tour in Cobble Hill and continued to do similar short tours in locales like Greenwich Village and New Springville, Staten Island that fall, winter and spring for other book signings as well.

You never know how these events will turn out. When Forgotten NY The Book was number one on (the late lamented) Book Court on Court Street’s Christmas best sellers list in 2006, I arranged with them for a book signing. At which no one showed! I’ve had tours for which 3 people showed up, and tours that attracted 50 and over. It’s impossible to predict.

Looks like Grown & Sewn, #165 Columbia. offers “clothes, coffee, records, dogs.” Quite an eclectic selection! it’s actually a menswear shop.

A confession: I was never keen about getting clothing for Christmas, and to this day, I still wear items I bought 30 years ago. When my clothes get holes in them I finally throw them out.

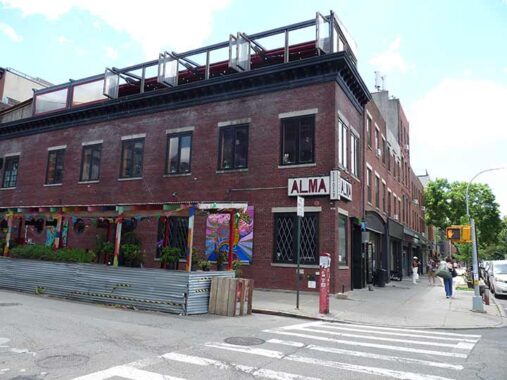

South of DeGraw Street Columbia Street abandons the waterfront and becomes a modest restaurant row. Alma is a well-regarded Mexican restaurant at Columbia and Degraw Streets noted for its rooftop deck, open to the air in spring and summer.

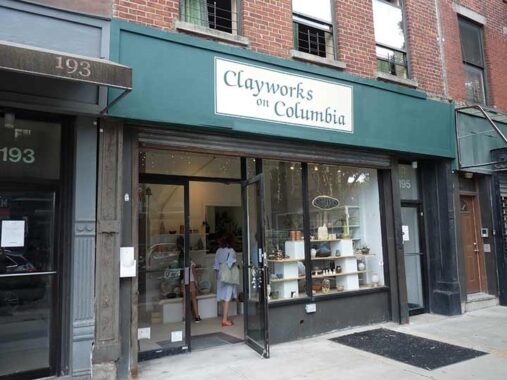

I recognized the font on the sidewalk sign at Clayworks on Columbia, #195 Columbia, right away; it is of course ITC Zapf Chancery.

At this point I wanted to turn east and explore Union and Sackett Streets. Here, Union and Columbia are the main axis of the business district in Carroll Gardens west of the BQE. I have been paying more attention to honorific street signs; each one has a story:

Jose “Tuffy” Sanchez (1933-2005) was a Korean War veteran and a community leader in Red Hook. In the early 1960’s, he became co-owner of the 3&1 Social Club in Brooklyn. He was a pioneer in promoting Latin music, in clubs and concerts in many of NYC’s dance hall venues. In the late 1960s, he established the Teen Canteen which provided neighborhood youth with jobs and opportunities. He helped organize street concerts on Baltic Street in 1965, 1970 and 1976. He founded the nonprofit Puerto Rican Waterfront Corporation, funded under President Johnson’s War on Poverty, as well as the Neighborhood Youth Corps., a city -funded summer program. He helped create the Independent Neighborhood Democrats in Red Hook and campaigned against the destruction of the Columbia Waterfront neighborhood for a proposed Port Authority container port. [Red Hook Water Stories]

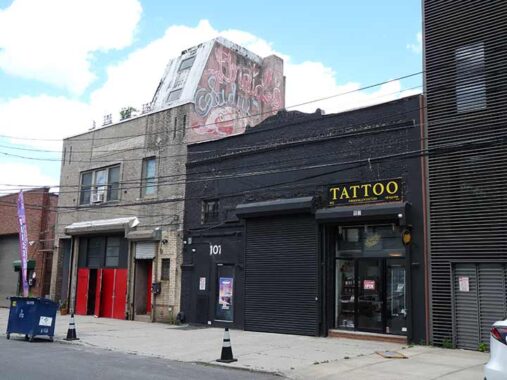

I have never been able to decipher the artwork on the “penthouse” at #99 Union Street west of Columbia. Some months ago, I remember receiving an explanation, but I can’t find it now. Next door, #101 Union is the former event and concert space Union Street Star Theater.

Former theater owner George Fiala:

The story of the Star Theater is that it began as a stable and around 1892 was converted into an Italian Marionette theater. I found an interesting 1899 Brooklyn Eagle article about it in their archives. Afterwards it was mostly an auto-repair shop, and then, for a few years a place where marble countertops were cut. I rented it last year, a sloppy mess, and fixed it up. Not knowing about the theater, I built a stage for my band to practice, and was then delighted to find out it was the place’s second stage. I host a weekly music jam every Thursday from 8-11 pm – the musicians play for free and I give out beer for free – a good deal for me I must admit because the music has been sometimes pretty amazing. On other nights you’ll often find bands practice there – actually three bands that have formed out of the jams (in one of them I’m the drummer).

Between Columbia and Hicks Union Street, in addition to the 25′ lampposts, is illuminated by some Type B park posts, as is Atlantic Avenue further north.

Ferdinando’s at #153 Union just off Hicks was a testimony to Carroll Gardens’ and the Columbia waterfront’s Italian heritage. It was in business since 1904 before abruptly closing in March 2025. Sicilian specialties were the forte, especially the flat bread panelle. The storefront’s venerable glass painted lettering is still there and the now-fading handpainted sign, with an unusual triskelion cherub.

ForgottenFan Robert Oppedisano: the panelle at Ferdinando’s are chick pea flour croquettes, fried, sometimes served in a Sicilian seeded bun with shaved provolone and ricotta (great). The name refers to the croquettes, not the sandwich.

The restaurant was due to reopen under new ownership and a new name, but I have yet to see or hear anything regarding this.

Noting #134 Union Street for its raised-lettered sign in brass or wood in the ITC Garamond Bold font.

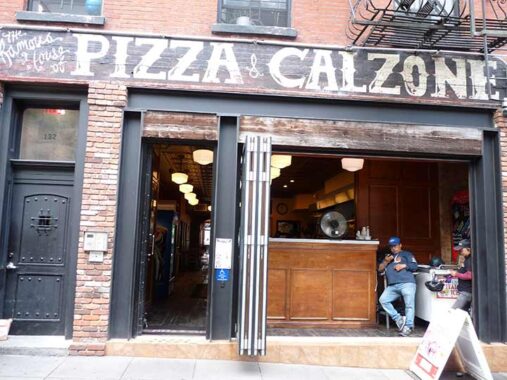

Not sure how long the hand lettered sidewalk sign has been there but House of Pizza and Calzone at #132 Union, founded in 1952, is the second oldest establishment, after Fernando’s, on the block. Brooks of Sheffield has the whole story on Lost New York.

Between Columbia and Hicks, Union Street is the main shopping drag of the Columbia waterfront district, at least for practical stuff, and the city has placed some type B Henry Bacon park lampposts on the sidewalks.

I was wondering about 131-133 Union, which appeared to have some importance in decades past. Again, Brooks of Sheffield at Lost City has come up with the answer:

This is the most imposing building on the block between Hicks and Columbia (note the double address), and one quick glance at it will tell any free-lance historian that it was once a bank. Note the faux marble pillars, the vaguely classical architecture, the high doorway, the fake balconies. Of course, in the isolated Italian ghetto that this neighborhood once once, it wasn’t a bank the way you and I think of them. It was a private banking house, owned and run by one Antonio Sessa and his son Joseph…

|

The Sessas were obviously major community leaders. I was once told a story by a local that, during the Depression, the bank was the subject of a run, but that Sessa, George Bailey style, talked all those who had money in the bank out of withdrawing their funds. The Sessas were also arts supporters. They invited Guglielmo Ricciardi, the founder of the first Italian-American theatre troupe in Brooklyn, into the back of his bank, where he and various amateurs thespians would rehearse various comedies. Sessa provided financial support. And a bank clerk named Francesco De Maio helped the company rent the Brooklyn Athenaeum, which used to stand at the corner of Atlantic and Clinton, and was a cultural beacon for the area.

|

Banco Sessa was absorbed by Bancitaly in 1927. Joseph Sessa still ran the bank, though. Then in 1928 Commercial Exchange Safe Deposit Company bought it. The address was First National City Bank by the 1950s, with Sessa still there. At some point it became Citibank, which eventually decamped to its present location on Court Street near 1st Street.

The Salvator Mundi Museum of Art, 144 Union Street, entrance on Hicks, has one of the most inauspicious exteriors of any museum I’ve seen. I may stop in next time I’m around.

From its website: Taking its name from the world’s most expensive work of art, the purported lost masterpiece by Leonardo da Vinci, the Salvator Mundi Museum of Art is dedicated to exploring all aspects, implications and ramifications from the Salvator Mundi story and art history.

|

On November 15, 2017, history was made when a painting titled Salvator Mundi, attributed to the great renaissance artist Leonardo da Vinci, completely shattered all records by selling at Christie’s auction house in NYC for just over 450 million dollars. The painting, dated from around 1500 and lost for many years, was thought to be rediscovered in 2005 underneath multiple layers of overpainting, torn and decayed by worm holes. Over the next 6 years it was meticulously reworked and restored led by conservation expert Diane Dwyer Modestini at New York University.

|

This museum houses one of the largest private collections of art and ephemera surrounding the Salvator Mundi story and regularly mounts exhibitions on a multitude of related areas of study.

|

The Museum is approximately 45 sqft. in total and is viewable through the exhibition space glass area. Private tours are available on request.

The Museum is open daily from 9 AM to 10 PM.

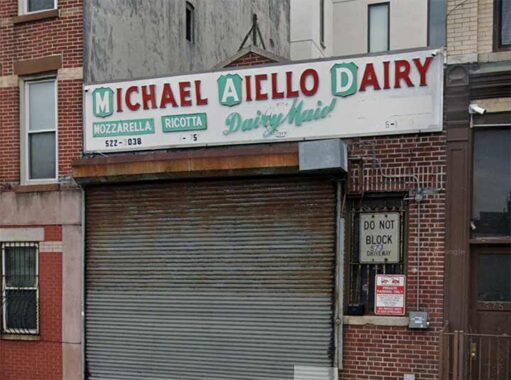

Speaking of inauspicious, the Michael Aiello Dairy sells Italian dairy goods out of a garage on Hicks Street south of Union on the east side of the BQE. What attracted me was the plastic-lettered sign in the red, white and green of the Italian flag.

In Part Two: Sackett and Berkeley

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

12/28/25

8 comments

Voorhees is actually preceded by Jerome Avenue and NOT Avenue Z! Yest it is named for the Jerome family who had horse racing interests in Sheepshead bay.

Jerome Avenue is a diagonal pathway. It was originally the south boundary of the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack

The Voorhies family were large landowners (farmland) in that part of Brooklyn. Hence, the name. Original spelling may have been Voorhees.

I used to pop into the Montero bar once in a while when I was in

the national maritime union,some of the antiques have disappeared

over the years,legend has it that the writer Frank McCort used to live upstairs

As I live in Brooklyn Heights, I have shared the link for this with numerous people and blogs across three continents!

A bit of Atlantic Avenue history: The original section of Atlantic Street, as was then known, was laid out in 1829 on a map of property of Ralph Patchen. This, along with Pacific Street, soon made the earlier District Street redundant and led to its closure. Atlantic Street was subsequently extended eastward. As Atlantic Street, intended in 1835 to extend east to Clove Road. (The Long-Island Star, Thursday, February 12, 1835)

“The Street Committee reported adverse to changing the name of Atlantic street to Broadway. Accepted and adopted.” Common Council, August 27, 1836, reported in the Long – Island Star, September 1, 1836

Section west of Flatbush Avenue originally known as Atlantic Street; renamed (for continuity as it was already an avenue east of Flatbush Ave.) to Atlantic Avenue by the Common Council on November 29, 1869, effective December 13, 1869.

The section east of Bedford Avenue was originally laid out on the Commissioners’ Map of the City of Brooklyn, 1835 – 1839 as part of the former Schuyler Street, named in honor of Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, American Revolutionary War hero.

Kane Street was originally a part of Butler Street. Butler Street between Court Street and the East River was renamed Harrison Street by the Common Council on June 21, 1841, likely in honor of President William Henry Harrison, who had died on April 4th of that year after having served only a month in office. (The Brooklyn Evening Star; Wed, June 23, 1841; page 2) Changed to Kane Street in April 1928. (The Brooklyn Citizen; Thu, Apr 26, 1928; page 6)

As I had also once been intrigued by seemingly unusual images similar to the “triskelion cherub” in the picture regarding Fernandino’s, I endeavoured to learn more, and as it turns out that symbol is called the “Trinacria” and features prominently on the Sicilian flag. (Sorry if duplicate comment here — went through absolute reCaptcha hell to bring you this important message…)

Van Voorhees Playground is the site of Kelsey’s Alley, which was probably wiped out when the BQE was built. My great-great grandfather, David Cuddy, was listed in the Brooklyn City directory of 1850 as living there.

Bill W.