There are still some parts of Manhattan I haven’t been in with regularity since I began photographing this website in 1998, and the area in the West 140s from St. Nicholas Avenue west to Riverside Drive has been one of those. Funny because I’ve spent a lot of time in the City College area, to its south, and Washington Heights, which begins at West 155th, to its north. However as you will see, there are a couple of items I have covered extensively before, and I just can’t help myself, I’m attracted to them the way I’m attracted to pizza.

The area was named for Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Treasurer and co-author of the Federalist Papers, who built his home, known as Hamilton Grange, in the area in 1802. I passed by the place on this walk, but I have previously published a lengthy page on the Grange in 2012, so I’ll blithely pass it over on this occasion. It looks better than ever now that it has been moved to St. Nicholas Park.

GOOGLE MAPS: My route for Hamilton Heights to Harlem

When I left off in Part 1, I had arrived at Riverside Drive and West 149th Street; I walked down Broadway a couple of blocks, then zigzagged southeast.

Hey, I forgot to mention this building at the NE corner of Riverside Drive and West 150th, across from the Ralph Ellison Memorial. It’s one of hundreds, or even thousands, of apartment buildings in upper Manhattan designed, as I call it, with “casual elegance.” Ornamentation, considered gtawdry and a waste of money by modern architects, was a big part of the design in the early 20th Century and this building features some design “Easter eggs” on the corner, circular bas-reliefs depicting, I think, owls, seahorses and other creatures. I didn’t initially notice them and so I didn’t zoom in on them, but they’ll be there next time you’re in the area.

I zigged down Broadway before zagging east and south. This is, unfortunately, what’s left of the once-piquant Bunny Theatre at West 147th. “Bunny” had nothing to do with Bugs or Hefner; it was named for Silent Era actor-comedian John Bunny, who appeared in hundreds of films and is buried in Evergreens Cemetery. The Bunny in its glory can be seen on this FNY page.

This is a new-ish (placed in 2001, replacing a 1909 original sponsored by the Daughters of the American Revolution) plaque in Broadway’s traffic median at West 147th commemorating the Battle of Harlem Heights in September 1776, in which Gen. George Washington forced a British retreat.

The old Hamilton Theatre, with its collection of mermaid-ish caryatids, is on the NW corner of Broadway and West 146th Street. It was built in 1913 (Thomas Lamb, arch.] and operated as an 1850+ seat vaudeville hall and movie theater until 1958; since then, the building has served as a boxing ring, a church and, as the Hamilton Palacio, a disco. The theatre itself has been left to ruin for the most part but a private investor, Ben Ashkenazy, purchased it in 2013. So far there’s been no word of restoration, though with the high-profile restorations of the St. George in Staten Island and the Loew’s Kings in Flatbush, perhaps it may be in the cards for the future. The bones are still in place. The NY Daily News has some interior photos.

Because of hilly topography, there are just three streets in Manhattan that run from the Hudson to the East Rivers, or from Riverside Drive to the Harlem River Drive, north of 125th Street: 145th, 155th and 181st. The stretch of West 145th between Broadway and Amsterdam includes some gems and reclamation projects, such as the old PS 186 at #521, which is being gutted and converted into a new home for the Boys & Girls Club of Harlem, along with a mix of low-income, ‘affordable’ and market-rate apartments.

A pair of nearly identical hotels, the Hotel Caribe and the 511 Hotel (a.k.a. Casablanca Hamilton Heights Hotel), are separated by two walkup apartment buildings. The awnings are in the same style but in different colors, so they likely share an owner.

A Hotel Caribe yelp.com review…

Let me preface this by saying I only walked into the lobby as I was passing through the neighborhood. If you are looking for a place to stay for really cheap (like less than $90/night), this place has rooms that share a common bathroom. Rooms with their own bathroom were $95/night, I believe.

But the kicker…you can rent a room for 2 hours for like $65. Yes, this rate card was on the bullet proof plastic window at the front desk. I did not see a room, but I thought this was hilarious. I had never been in a hotel that rents by the hour before.

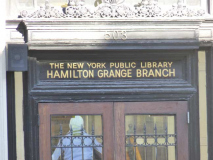

The Hamilton Grange Branch of the NY Public Library was completed in 1906 [Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White, arch.] was paid for by Scottish industrialist/philanthropist Andrew Carnegie’s $5 million donation (in 2015 that would be real money!) The AIA Guide to New York compares it to an Italian palazzo. I liked that hand-gilt lettering on the transom.

The building next door is a product of a different architectural philosophy; the inscription “Phase: Piggy Back” is a drug treatment center. The menorah at the top tells me it was built as a synagogue, and may still be used for that purpose for an uptown Jewish congregation.

Mishkin’s Pharmacy, southwest corner of W. 145th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, has been an old-school staple for many years. It has recently streamlined its interior, but kept the tower neon sign and hand-lettered signs on the corner doorway pillar. Scouting New York arrived in 2013 and shot the interior before its renovation:

According to the store’s website, Mishkin’s was started in 1890 by a Russian Jewish immigrant. Later, it appears that Mishkin’s became a New York chain, with a location at 116 W 14th Street by 1964 and another on Columbus. A third Mishkin’s still exists in Brooklyn at Broadway & Kosciusko Street. The Mishkin’s at 145th was purchased by its current owners, Mr. & Mrs. Yoo, around 30 years ago.

In 2014, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Mishkin’s still looked reliably old-school on the outside, with painted signs and a neon “Cut Rate Drugs” sign with a vessel with the pestle.

Heading south on Amsterdam there’s an example of how the Department of Transportation has combined new styles with old. The massive, guy-wired stplight design shown here debuted in 1952 or 1953 and for many years was used at only the busiest intersections. Starting in the 1980s, though, it began to assume much more of the traffic control load. Had traffic massively increased in those thirty years?

The “Corvington” style of long-armed “boulevard lamp” debuted in 1902 and, after using a somewhat simplified scrollwork (ornamentation between the mast and shaft) proliferated mightily on NYC streets before a phaseout began in 1950.

When the DOT re0introduced the style in the 1980s, along with the Bishop Crook and Type F styles, the guy wired stoplights posed a problem. The DOT had no intention of returning to the ornate “Wheelie” style stoplights, and anyway, there was no provision for a streetlamp in addition to the stoplight on them. What the DOT did was leave the guy-wired stanchions in place, and place new versions of the old designs on top of their shafts, creating hybrid versions. Purists may holler about these hybrids, but I rather like them.

Speaking of hybrids, we have another one here — it’s nothing new. This monumental Twinlamp post stands at the northern peak of the Triangle formed by Amsterdam Avenue, Hamilton Place and West 144th Street. At first glance you can tell there’s something different about this Twin. I’ve featured it before in FNY, and led tours past it, but till recently I figured out something new about it.

The top resembles the classic Twin in most ways, but there is more ornamentation and rosettes around the connectors that hold the lamps (unfortunately, still some ugly “bucket” sodium lights left over from the Easy Eighties). The finial is different, too; I call it a “German helmet” because of the spike. There’s also a short version of a ladder rest on the shaft.

Meanwhile, the bottom of the shaft is a different creature entirely. No surviving Twin, or any other old castiron post in town, has this amount of heavy ornamentation on it; it seems truly over-the-top. I’d have to say that all this metal prevents it from tipping over in case a vehicle ran into it; but when the post was built, likely the 19-ohs or 1910s, the pole had to fear horses and carts and not many vehicles bigger than that.

However, I’ve got evidence that this, too, is a hybrid lamppost. Here’s a page from a 1936 NYC lamppost survey I have in my possession. The name of this post is a “Type 24 Twin, Variation 3.” The variation is in the crossbar, which has the extra ornamentation and German helmet spike seen on the Amsterdam Avenue post. The bottom, though, is the familiar castiron post seen on thousands of lamps around town.

Meanwhile…from the same survey… here’s a Type 6 Twin post. The base is the massive on that we see on Amsterdam Avenue, but the crossbar is a type that no longer exists. It’s gone extinct.

Ok, what happened? Well, here’s a crude composite of the two that I made up. At some point, decades ago, the top of the original Type 6 Twin post fell off. Maybe a truck ran into it, and it’s hard to imagine anything other than a big bomb dislodging that base, but the narrow shaft was toppled.

The city had no remaining versions of the original Type 6 Twin to replace it, so the city turned to another design it still had some examples of… the “Variation 3” Twin.

In so doing, it preserved parts of two classic lamppost designs, but couldn’t preserve complete versions of both!

I discover new things about this post very time I go past it. On the base is a light bulb, the company logo of the NYE (see the notation on the above example)– he New York Edison Company, a Con Ed predecessor. NYC’s earliest castiron lampposts bear this motif on their bases. That marks this particular base as old indeed: 1905 to 1915 kind of old.

The triangle on which the lamppost is located is called Johnny Hartman Plaza:

Johnny Hartman (1923-1983) was a distinguished vocalist who is best remembered for his recordings of romantic ballads. Born and raised in Chicago, John Maurice Hartman began studying voice and piano at the age of eight, sang in his church choir and for his high school glee club, and won a scholarship to study voice at the Chicago Musical College. After serving in the army in World War II, Hartman returned home where he won an amateur singing contest which led him into a professional singing career, working with pianist and bandleader Earl “Fatha” Hines. In 1949, when Hines’ band folded, Hartman was recruited to sing with jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie; their collaboration was memorable because of the contrast between Gillespie’s ‘hot’ trumpet playing and Hartman’s smooth ‘cool’ baritone voice. Hartman sang briefly with the pianist Errol Garner and his trio. NYC Parks

A Johnny Hartman recording with John Coltrane:

For reasons known only to WordPress developers, no longer is the actual YouTube video linked. Simply cut and paste the URL onto a new tab or window.

“There’s nothing you can do with a good song but sing it” — Johnny Hartman.

A doorway goddess, West 143rd east of Amsterdam.

At the bottom of the steep hill at West 141st Street and St. Nicholas Avenue is the Gothic Revival St. James Presbyterian Church, built in 1904 as the Lenox Presbyterian Church, opposite St. Nicholas Park and a bit east of the Hamilton Grange.

St. James moved to its present home in 1927. Located on the northwest corner of 141st Street and St. Nicholas Avenue, the church was designed by Ludlow & Valentine and built from 1904-05 for the Lenox Presbyterian Church (later known as St. Nicholas Avenue Presbyterian Church), which remained there until they merged with North Presbyterian Church on West 155th Street.

During St. James’s first decades on West 141st street, it was led by the Rev. William Lloyd Imes, described by the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., as having ‘the mind of a scholar, the soul of a saint, the heart of a brother, the tongue of a prophet, and the hand of a militant.’ St. James is also noted for its music. Dorothy Maynor, soprano soloist and wife of the pastor, The Rev. Shelby Rooks, was an operatic soprano who was barred from a career in opera because of her race, although she was a famous recitalist. In 1964, she founded the Harlem School of the Arts in the basement of St. James, teaching piano to a dozen children. The school is now housed in a building north of the church and attracts about 3000 students annually. NYCAGO

Mount Calvary United Methodist Church, Edgecombe Avenue at West 140th Street, constructed in 1897 as the Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Atonement. Mount Calvary was established in 1920 and is now one of the largest Methodist congregations in Harlem.

“Edgecombe” comes from an Old English word meaning “edge of the hill.” North of here, Edgecombe Avenue is the western border of High Bridge Park, on a bluff overlooking the Harlem River.

Looking west at Edgecombe and West 139th Street imparts a majestic view of CCNY’s Shepard Hall.

Shepard Hall is the anchor building of the campus, occupying a plot between Convent Avenue, St. Nicholas Terrace and West 140th Street. It is anchor-shaped with two wings proceeding from a central section. The 185′ x 89′ x 63′ Great Hall, which can host over 1,000 people, is the centerpiece of Shepard Hall and is dominated by twelve massive columns and Gothic peaked windows. Shepard Hall hosts CCNY’s Schools of Architecture, Urban Design and Landscape Architecture, the department of Humanities, a music library, the college’s alumni association as well as several other offices.

A whimsical touch imparted by Post is the presence of stone grotesques and gremlins on the exteriors. One of them holds a model of Shepard Hall!

St. Mark’s Methodist Church, West 138th between St. Nicholas and Edgecombe Avenues, constructed between 1921 and 1926. “With its stone facing and massive square central tower, the edifice harmonizes with the Collegiate Gothic buildings of the City College campus, located up the hill across St. Nicholas Avenue. St. Mark’s building includes a large sanctuary that is very wide with a large curved gallery, and an attached community house. The cornerstone was laid on September 9, 1924, and the completed church was dedicated on December 5, 1926.” –NYC American Guild of Organists

West 138th Street between Frederick Douglass and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevards (8th and 7th Avenues in the old days) is one of two streets, along with West 139th, that form the St. Nicholas Historic District, consisting of various groupings of attached houses (146 in all plus 3 apartment buildings) commissioned by developer David King (he built the first Madison Square Garden, which was actually at Madison Square, and the base of the Statue of Liberty). The famed architectural form McKim, Mead and White was one of three such who worked on the project.

King was able to assemble the buildings relatively cheaply, by buying in bulk, and sold them to working class and middle class buyers; hence, the two streets became known collectively as “Striver’s Row.” Most were built between 1891 and 1893 but it wasn’t until about 1919 that the houses were sold to African-Americans when they began to move to Harlem from points further south. Various homes in the district belonged to architect Vertner Tandy, boxer Harry Wills and musicians W.C. Handy, Eubie Blake and Fletcher Henderson.

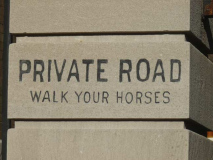

Perhaps King’s most notable addition to the district are the service alleys, or cross streets, protected by iron gates. Originally, horses were walked to the rear of the houses using these alleys and a couple of the signs reflecting this have survived.

On the same block, the Victory Tabernacle Seventh Day Church holds forth in a converted real estate office.

This rather elaborate structure was built as the office of the Equitable Life Assurance Co. (1896-1923), the mortgage holders for the King Model Houses who had repossessed the properties in 1895. After selling off the houses to black families after 1919, they closed this office. It became home to the Coachmen’s Union League Society of New York (1923-28). The CULS was founded after the Draft Riots in 1864 to promote equal rights and provide sick pay and funeral benefits for black coachmen. Since 1942, it has been home to the Victory Tabernacle. — Matthew X. Kiernan

“Kings Court” is a nod to original developer David King.

This brick building on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Blvd. between West 137th and 138th Streets was a major mecca of Harlem nightlife in the 1930s in its incarnation as the Renaissance Ballroom. The “Renny” offered dancing, cabaret acts and the finest bands of the era, including those of Vernon Andrade, Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb. Its builders were William Roach and James Sweeney, from Antigua and Montserrat in the Caribbean Sea.

The adjoining Renaissance Casino was the home court of the 1920s Harlem Rennies, the first all-black professional basketball team, which racked up a 2588-592 record against other local competition in the pre-NBA era.

Unfortunately the buildings have been deteriorating for decades and soon may be “transformed” into a residential complex:

The new owner of the crumbling 1920s hall and theater plans to transform the dilapidated venue into an eight-story building with 134 apartment units, according to records BRP Development Corp. filed with the city’s Buildings Department.

The proposed mixed-use complex will also include more than 22,000 square feet of community space and about 18,000 square feet for retail shops.

It will be named “The Renny” after the historic ballroom, which was constructed and operated by black businessmen before it closed its doors in 1979. NY Daily News

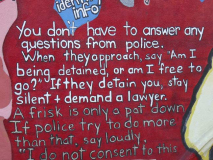

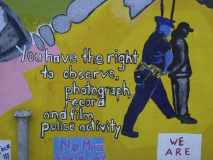

This wall mural at Powell Blvd. and West 138th Street opposing overaggressive police tactics dates to 2013, a full year before the Eric Garner incident or the events in Ferguson, MO.

It was kick it in the head for the day time, and I headed to the 135th Street subway station at Lenox Avenue, one of the stations decorated in Beaux Arts style by Heins and La Farge in the 19-ohs, featuring handsome terra cotta plaques festooned with tulips.

2/22/15

11 comments

.

.

Nice tour Kevin.

Some beautiful churches up there.

.

>> Because of hilly topography, there are just three streets in Manhattan that run from the Hudson to the East Rivers, or from Riverside Drive to the Harlem River Drive: 145th, 155th and 181st.

Huh? Maybe you mean in that section of Manhattan (145th to 181st), but there are certainly others elsewhere in the borough. 34th St. is the one that came immediately to mind, as it directly intersects both the West Side Highway and (service roads of) the FDR drive, and runs without interruption between them. 14th, 23rd, and 42nd come damn close too. Plus 96th (if you count the transverse road as part of it) and 125th, and further north, Dyckman St. I’m sure there are others.

Actually, not 14th, I forgot about the Con Ed plant at its east end. Based on a check of Google Maps, the following streets do run uninterrupted between the FDR Drive (service road intersection or interchange) and the West Side Highway: 20th, 26th, 30th, 34th, 42nd, 48th, 49th.

Okay, but READ THE DAMN HELL *AGAIN*!!: the webmaster said that their are just three streets in Manhattan that run east-west from river to river *north of 125th Street*. So he DOES mean in that section of Manhattan.

I meant, “…there are just three streets…”, of course.

The Type 24 Twinlamp shown in the catalog reproduction above was in every Upper Broadway median between 60th and 168th Streets, until the early 1960s. Remember them well.

I have always viewed upper Manhattan neighborhoods as feeling as if they sometimes feel as if they aren’t even part of the borough considering that most of their blocks look like something you would probably in most of the boroughs excluding Staten Island.

There is bad news for you regarding Mishkin’s Pharmacy: http://www.scoutingny.com/mishkins-is-gone-forever/

The bad news is they removed a lot of the interior but did retain the original tile floor and tin ceiling, both of which were covered up.

As a former resident of the neighborhood, I appreciate your visit. Some sites you missed include the once-grand former synagogue on 149th Street between Broadway and Riverside, that is now a church and is masked by an apartment building apparently raised over its lobby area. I wonder what they did with the basement mikvah (ritual bathing pool).

There was also a small brownstone (no stoop) once-synagogue just across Broadway, possibly on 148th Street, with its name still inscribed over the door.

I nearly took an apartment in the grand building at 150th and Riverside (I would still be there if I had, but I was driven out of the neighborhood by the rampant Dominican drug dealers and crooked cops), and was told by the super that it once had a casino for residents on an upper floor, and that Senator Jacob Javits had lived there. The one-bedroom apartment I saw was formal, and had, in addition to a formal living room and dining room, a maid’s suite off the kitchen, and a butler’s pantry hallway parallel to the actual hallway, inside the apartment. It was too amazing for me at the time.

I sincerely hope you still monitor these comments. I must tell you that I got very emotional, literally teary eyed reading this and looking at the incredible photos. I am in my

60s, and left NYC in 1976. But I lived at 400 Convent Avenue (at 147th Street) as a teen into my early twenties. You have truly done a wonderful job here and some of your pictures brought back such memories. I still miss New York, though I love L.A. I always knew our Hamilton Heights/Sugar Hill neighborhood was special. I loved to often

walk down to City College and just explore. It was just a lovely neighborhood and it shocked me that somehow it always stayed better maintained (like Strivers Row) and

never became as run down as other parts of Harlem. It still pains me deeply that our apartment on Convent was stolen from us when the building went condo. The

apartments are in the $1,000,000 range now. Anyhow, really great job. Have you ever done 555 Edgecombe Avenue. My dad used to live there. You probably know it’s a

very famous building with National Historic Landmark status now and many jazz greats lived there. By the way, Butterfly McQueen (Gone With the Wind) lived on 147th

street between St. Nich and Convent for awhile. I was coming home from work one day, heard her shout out to someone and knew who it was before I saw her about to

enter her building.

and Convent for a time.

Great website. Thank you!