It’s become something of a series.

A few years ago I set off under the Westchester Avenue El between Parkchester and Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx, and finished off my journey “under the 6” some time later. Then, Sergey wrote about Livonia Avenue and I walked the length of New Utrecht Avenue, both of which are mostly covered by elevated trains. I had previously done Fulton Street in Cypress Hills and Jamaica Avenue in Woodhaven. My very first ForgottenTour in June 1999 explored the underside of Brooklyn’s Broadway. Part of my Myrtle Avenue extravaganza was under the section that still had an elevated train.

I have yet to do the other “elled” section of Westchester Avenue under the #2 train, as well as White Plains Road that supports the #2 and #5. Had there been a Forgotten New York in the 1930s, there would have been pages on the 2nd, 3rd, 6th and 9th Avenue Els. As it is now, only a very small section of el still stands in Manhattan, but it runs over three separate streets — that will be the subject of a walk I did recently in Manhattan and the Bronx.

Why els? When you were a kid, I’m sure you used to upend rocks or logs in the park to see what scurried out when you did — ants, worms, etc. that are sources of endless fascination for kids. For me, now writing in my 50s, fascination has always come from seeing anomalies and leftovers from previous eras that somehow have survived under els where city agencies can’t see them such as signs, lamps and even unchanged stores and businesses. Thus, I walk in darkness, under the els.

Recently I traveled under the Astoria El between Queens Plaza and Ditmars Boulevard. The Queens and Queensboro Plaza areas — the latter is used only on the joint platform serving #7 and N trains — have been so named since about 1910, when the Queensboro became the first bridge to connect Manhattan and Queens. It opened up vast areas of western Queens for development and what had been a relatively quiet area on the edges of both Hunters Point and Dutch Kills became a transportation mecca. Construction for elevated trains to Astoria and Corona (eventually Flushing) was under way by 1915. Manhattan’s Second Avenue El was extended over the Queensboro to meet those lines at Queensboro Plaza, which filled two separate platforms over Queens Plaza North and South which had renamed from Jane Street.

Businesses were attracted to Queens Plaza and its environs, as cars and even airplanes were produced at the Brewster Building, which still stands though its corner clock was taken down in 1950. In Sunnyside, across the vast trainyards serving railroad lines passing through Penn Station, a vast manufacturing district sprang up

Trolley lines also fed the elevated train traffic. In the 1930s, the city’s Independent Line created an express subway stop at Queens Plaza (though no transfer was made available to the three elevated lines at Queensboro). By 1942, the first cessation of public transportation occurred as the Second Avenue El ended service, though by then the Flushing Line IRT and 4th Avenue BMT lines were well-established. The end of the 2nd Avenue El did bring some sunlight to the plaza, as half of the elevated complex was razed.* Trolleys were eliminated gradually throughout the late 30s to the mid-50s, though one of NYC’s last trolley lines stopped midspan on the Queensboro at an elevator that took visitors to patients on Welfare (now Roosevelt) Island’s many hospitals and institutions, most of which have now vanished.

*See comment below.

For decades, while el traffic remained busy, Queens Plaza languished as the manufacturers vanished and were replaced by fast food joints and “gentleman’s clubs.” While Queens Plaza was home to a vast parking lot called “JFK Commuter Plaza,” one of NYC’s ugliest buildings, a Brutalist-come-Jetsons parking lot, was built at Queens Plaza and Jackson Avenue (it can be seen in all of its “unglory” on this FNY page). Something had to give.

Queens Plaza, a maze of traffic and elevated trains located at the foot of the Queensboro Bridge, has recently undergone a $45 million makeover. Its traffic patterns have been rerouted, a bike path has been added, and its landscape has been redesigned. The largest new addition to the plaza is a park named Dutch Kills Green, which is located atop [the former JFK Commuter Plaza] on the plaza’s eastern end. This 1.5-acre park is an island surrounded by elevated subway trains and a nonstop flow of cars, buses and trucks. It borders several abandoned and empty buildings. The park houses a native-plant wetlands, a collection of artist-created benches, a small amphitheater, and two Dutch millstones from the 1600s. — curbed

As part of its makeover, Queens Plaza traffic patterns were rearranged and its traffic medians decorated with broken stones. Pedestrian footpaths lead through jagged rocks between multiple lanes of traffic. After complains from locals, most of the ugly rocks have been removed.

Once Long Island’s sole “skyscraper,” the 15-story Bank of Manhattan building, was finished in 1927…something The Fountainhead’s Howard Roark himself may have conceived of. That year, American architecture was shedding Beaux Arts and adopting the more streamlined techniques of the Machine Age. That didn’t stop the Bank’s architects from adding all kinds of Easter eggs way up high, like the 4-sided clock, the water bearer, fish and shell.

Long Island Star- Journal, October 1925: The Bank of Manhattan’s new building for Queens Plaza will set the pace for the Long Island City skyline. The building will tower far over the present buildings. The projection is that Bridge Plaza will be the new Times Square of Queens [italics mine-KW]. The 14 story building is to be graced with a four faced clock. The Plaza is expected to become the business and financial center of Queens. Transit facilities give it access to the South Shore as well North Shore.

In 1650, Dutchman Burger Jorissen constructed a grist mill that today would be on Northern Boulevard between 40th Road and 41st Avenue. The mill existed on the site for about 111 years, until 1861 when it was razed by the Long Island Rail Road. The Payntar family by that time owned the mill property (40th Avenue was called Payntar Avenue until the 1920s) and had placed millstones that had been shipped in by Jorissen around 1657 in front of their house. When Sunnyside Yards, Queens Plaza and the elevated were constructed, the millstones were fortunately preserved and embedded in the traffic plaza; after being removed for a time while Dutch Kills Green was constructed, they were replaced here, unfortunately open to the elements.

Thus far, efforts to move them indoors to a protected environment, such as the Greater Astoria Historical Society, have proven unfruitful.

The 21-story, 662,000-square-foot Gotham Center office tower (near background) replaced the Queens Plaza Municipal Parking Garage (the ugly one mentioned earlier) at the corner of Queens Plaza and 28th Street and has more than 180 parking spaces and 9,400 square feet of retail space on the ground floor.

4,000 employees of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene started moving in from locations in Mid- and Lower Manhattan moved in when the building opened in 2011.

Queens Plaza continues its transformation from destitution to whatever future awaits it. You can be sure of one thing: lower and middle class residents are not part of this intended transformation; they never are. (End of rare FNY editorial).

The el complex splits in two at Queens Plaza, with spurs headed to Astoria and Corona. The Astoria spur actually travels over Northern Boulevard for a few blocks; rare is the lengthy NYC roadway, excluding those in Manhattan, that do not have an elevated train over part of its route. As Route 25A, Northern Boulevard, under a variety of different names, continues out to the end of the northern fork of Long Island, Orient Point.

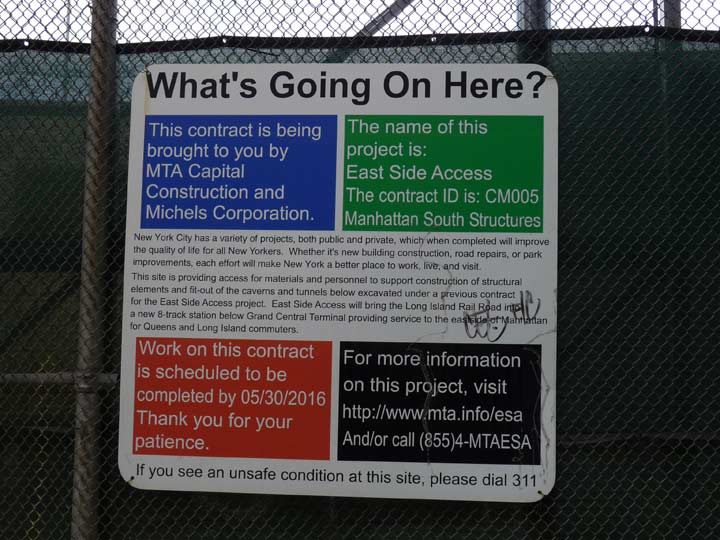

Here, Northern Boulevard passes over a large hole in the ground where a tunnel is being dug for “East Side Access” or a plan to route some Long Island Rail Road trains into Grand Central Terminal; a simultaneous plan is for some Metro-North trains to go to Penn Station. The plan has run into innumerable delays, the latest being the location of the water table under Sunnyside Yards, which was constructed on swampy ground in the first decade of the 20th Century.

Though some of the tunnel had already been built in the 1960s and 1970s (there is a “secret” second level to the Roosevelt Island and Lexington Avenue stations opened in the 1980s that had been planned for rail service to eastern Queens and has been added to the East Side Access Project), the plan, first announced in the 2000s with a “completion” date of 2013, now runs into the 2020s. Obviously this sign is way out of date but really, what’s the sense of updating it since no one really knows when ESA will be finished.

Remember what I mentioned about signage and lamp anomalies found under els? Here’s one at Northern Blvd and 40th Avenue where there’s an original fire alarm lamp designed for the modular Donald Deskey posts still in place. The Deskey posts first appeared in 1958 and by 1965 were seen in the thousands on main and side streets as well as expressways.

The post’s fire alarm lamp cover never fit too well, and by the late 1960s many were being held in place with string and tape, and that fate befell this one, too. Beginning in 2000 the city installed new fire alarm lamps and stopped maintaining the older ones.

A number of automotive services on Northern Blvd. under the el. Note the laughing bear for Bear wheel alignment tools.

These bear signs were produced by Bear Manufacturing, a nationwide chain. Shops used these signs to indicate that they were trained by Bear and used Bear wheel alignment tools. The yellow bear logo has been used by the company since the 1920s. He is often referred to as the laughing bear, the happy bear, or the dancing bear. The Grateful Dead rock band used the bear logo later, without permission. In the 1960s or 1970s, when Bear Manufacturing became part of Automotive Diagnostics, the company stopped producing the signs. However, they are now being produced again. Most of the remaining bear signs have been painted over numerous times. I believe these were all built in the 1960s and that the big ones all had neon. Roadside Architecture

I had noticed the bear years before when walking around what became Pacific Park, formerly Atlantic Yards (known by me as Ratnerville). But I had first noticed the bear in my grade school years since it turned up as a design element on the back cover of Allen Sherman’s My Son, the Folk Singer!

The Pennzoil logo is also rather venerable, as the company originated in 1963 when South Penn Oil merged with Zapata Petroleum and has used a variation of this logotype since then.

This post-top luminaire with a “cottage” style luminaire, as I term it, became quite prevalent under els, at least Queens’ Roosevelt and Liberty Avenues, beginning in the 1970s, but have gradually been changed out over the years till only a few isolated examples are left such as here on Northern Boulevard.

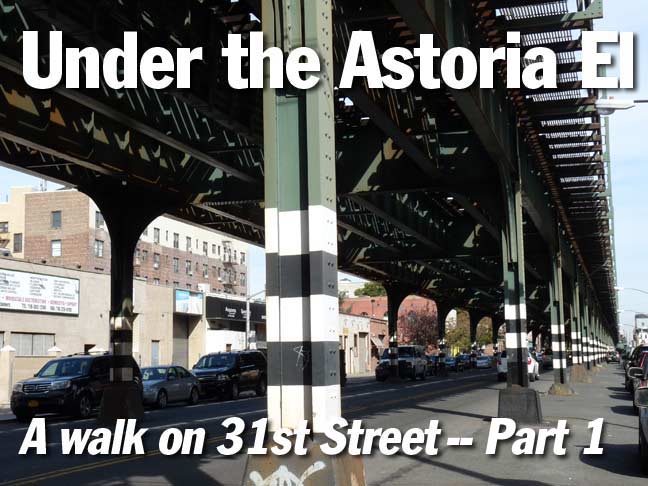

Here Northern Boulevard escapes into the light and proceeds east in an unshrouded fashion to the east end of Long Island. The el, meanwhile, continues up 31st Street, as did I.

The Universal Building, Northern Boulevard just east of 31st. This was a Ford dealership between 1913 and 1969, and I know this because in 2013 I spotted an incredible script Ford painted ad here while going past on the el.

The W train has been reactivated (it was previously retired in 2010) and will proceed on part of its old route: it will run between Whitehall Street and Ditmars Boulevard on the Broadway and Astoria lines, which also carry the N, Q and R lines. W service begins in November while the Q is due to be routed up the new 2nd Avenue line by year’s end. We’ll see.

Thank You for Your Service: Retired Subway Letters [FNY]

Coptic Church of St. George, 31st Street and 39th Avenue.

The Copts are an ancient Egyptian Christian sect. The Coptic Church predated the arrival of Islam in Egypt by several centuries; presently, there are 9 million Copts in Egypt in a population of nearly 60 million.

The Coptic Church is based on the teachings of Saint Mark who brought Christianity to Egypt during the reign of the Roman emperor Nero in the first century, a dozen of years after the Lord’s ascension. He was one of the four evangelists and the one who wrote the oldest canonical gospel. Christianity spread throughout Egypt within half a century of Saint Mark’s arrival in Alexandria as is clear from the New Testament writings found in Bahnasa, in Middle Egypt, which date around the year 200 A.D., and a fragment of the Gospel of Saint John, written using the Coptic language, which was found in Upper Egypt and can be dated to the first half of the second century. The Coptic Church, which is now more than nineteen centuries old, was the subject of many prophecies in the Old Testament. Encyclopedia Coptica, linked in above paragraph

39th Avenue (Beebe Avenue) station as seen from 39th Avenue. In the 1990s I was fascinated by this particular corner since the telephone pole still held a Westinghouse OV-25 Silverliner lamp; most had been changed out in favor of sodium lamps 20 years earlier.

For tradition’s sake alone, several stations along the Astoria Line still have secondary names harking back to when the streets were named, such as Beebe, Washington (36th Ave.) and Grand (30th Ave.)

Ghosts of the Subway: A Subway Street Necrology [FNY]

Another way of indicating a nearby fire alarm. These “top hat” red lights are usually attached to the photocell on a luminaire, but under the el it would be invisible there — so it’s affixed to the top of the cylindrical lamp shaft, very poorly. Like the Deskey alarm lamp they don’t really fit well here.

This example shows the new and old methods. The J-shaped bracket once held a cylinder-shaped orange plastic fixture covering a lightbulb. The city has stopped servicing them and installs red cylinders now.

The Marblette Corporation, on 30th just south of 37th Avenue. The company produced a molded colorful plastic as a competitor to Bakelite, used notably in radios and kitchen utensils. Its painted identification still survives here. Marblette was located on 31st Street from 1931 to 1982, but this sign appears to have been painted early on. Bakelite was named for its inventor, chemist Leo H. Baekeland, while Marblette was supposed to resemble actual marble.

I like shooting photos under els from across the street. The curved brackets used as supports on the el pillars make the scenes look like they have been framed with curved corners.

Long-abandoned building on the east side of 31st Street between 36th and 37th avenues. It had a partner on the corner of 37th, but that one was bulldozed about 4 years ago, leaving an empty lot that has yet to be built on.

While walking on 31st Street you will see a number of private standalone residences that were built during the years preceding the arrival of the el. Some have been aluminum sided into anonymity, but some have not…

…such as this one, that has retained the roof corbelling and porch pillar brackets it must have had for the better part of a century. Its next door neighbor may be similar in age but has had a ground floor addition and a stucco job on the second floor.

See what I mean about framing?

Here’s an across-the-street neighbor, which may have had several neighbors that looked like it before the two industrial buildings that surround it arrived.

The American Elevator building, 36-26 31st, is nothing to write home to mother about, but it still boasts a plastic letter sign dating back to the 1960s, at least. The still-active company (now American Elevator & Machine) has been in business since 1902.

Elevated station at 36th (Washington) Avenue. I spotted some interesting buildings on 36th, which I had never or rarely walked on, so I decided to have a look…

A collection of bay-fronted attached brick buildings on 35th between 32nd and 33rd Streets. These are more reminiscent of mid-Brooklyn locales like Windsor Terrace or perhaps Sunset Park.

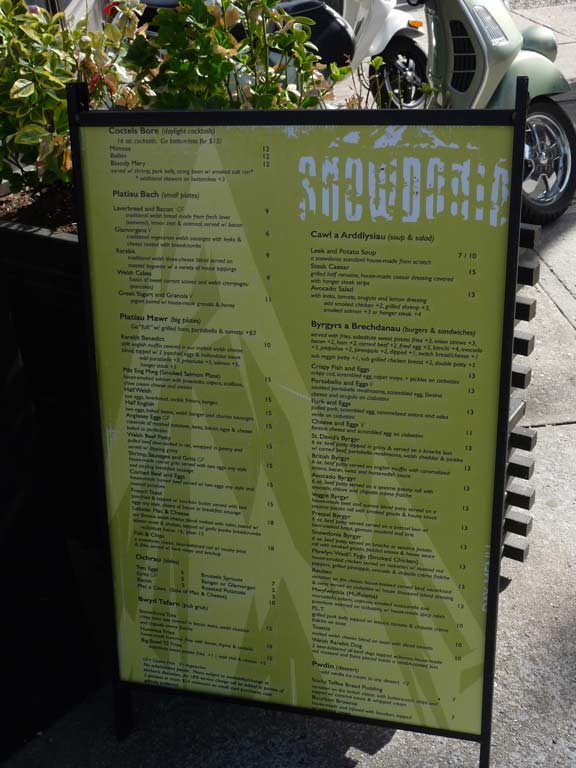

A corner building on 35th and 32nd has apartments on the top three floors and a restaurant called Snowdonia on the ground floor.

At first I thought it was named for information smuggler Edward Snowden, but then I noticed the different spelling. Instead, it is named for a mountainous region in eastern Wales.

The pub sells meals found in Wales, which is a great deal more than Welsh rarebit. The menu shows the names of their offerings in Welsh, which uses “w” and “y” as mid-word vowels a lot more than English does. (In Wales, a burger is called a “byrgyr.”) It has gotten decent yelp reviews and gets business from visitors to the nearby Museum of the Moving Image.

One of the reasons I enjoy Astoria so much is the varied housing stock. Here is an Art Deco apartment building (1925-1940) catercorner to Snowdonia on 32nd and 35th.

(In NYC, sidewalk scaffolding is forever.)

A matched pair of brick dwellings on 32nd that except for the doorways looks as if they must when they were constructed, likely around 1915.

Angry light bulb street art at 31st Street and 35th Avenue. Look carefully and see a shoutout to 5 Pointz, the graffiti artists’ collective building demolished in 2014.

The city has recognized the importance of frequent paint jobs on el lines to forestall rust, much more than in the past. 31st Street recently received a fresh coat with safety stripes, here continuing almost to the vanishing point on the horizon.

Taxi maintenance shops, recognized by their yellow paint jobs, between 34th and 35th Avenues.

As stated, there are still a number of private dwellings on heavily industrial 31st Street. This one has a plant trellis in the front yard, with just enough sun to maintain it. It had long ago received an aluminum-sided makeover.

I detoured west on 34th Avenue to see a house I had only previously glimpsed from the el. This isn’t it, on the corner of 34th and 30th Street, but I was taken by the contrast of the deep brick red and bright white window sills and lintels, as well as the special treatments give to 2nd floor windows on both sides.

As NJ 105 oldies DJ Don Tandler says, “They don’t make ’em like this any more and they don’t even try!”

Here’s the building in Question. It could be very old — it still has a slanted “mansard” roof popular in the 1870s — but frankly I was more impressed from the train. Aluminum siding has a way of homogenizing everything into architectural Velveeta.

I liked the doorway treatment across 30th Street a lot better. This looks to be a recent installment, though it has the same verve as doorways of decades ago. And, it’s hard to mess up an arched doorway.

These two-story, lengthy brick dwellings at 34th Ave. and 30th, likely built to fit to a narrow available plot, are among the handsomest I saw on today’s walk.

Second Donald Deskey post encountered on 31st Street, this one between Broadway and 34th Avenue. “Dwarf” Deskeys were made with shorter masts and shafts that could illuminate streets under elevated trains.

The Greek flavor of Astoria has been diluted in recent years. However, in some places it’s still quite strong. Also known as the Pancretan Association of America, the organization housed here benefits US residents who hail from the island of Crete.

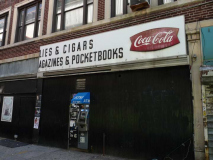

A pair of decades-old signs on 31st just off Broadway. Both date at least to the 1960s, one for a real estate office, the other for a corner candy store. The candy store sign once read “School Supplies and Cigars.” My guess is that Hurricane Sandy reduced it to just “Lies & Cigars.”

A very interesting building can be found at the NE corner of Broadway and 31st Street that likely predates the el. The roof treatments feature a number of caducei, or two snakes entwined around a staff. The symbol is associated with Hermes, the Greek messenger god (the Romans called him Mercurius) and it was generally found on commercial buildings from the 18th and early 19th Centuries. It was also used as a symbol for speed — a caduceus can be found on remaining stations or overpasses of the NY, Westchester and Boston Railroad in the Bronx, much of which is now the Dyre Avenue line (#5 train).

It’s a commonly made mistake equating the caduceus with the medical profession. In medicine the symbol is the Rod of Asclepius, which has one entwined snake, not two.

A second artifact can be found on the 31st Street side, where there is a remaining 2nd Avenue sign.

Long Island City, Queens, which once encompassed all of western Queens west of Woodside from the East River south to Newtown Creek, was once a city on its own (beginning in 1870) before Queens was absorbed by Greater New York in 1898. Even after the coagulation, LIC loomed large in Queens affairs, as its first Borough Hall was housed in the Long Island City Courthouse (finished in 1876, rebuilt 1904 at Jackson and Thomson Avenues. That courthouse is still used frequently for hearings.

Like the rest of Queens, Long Island City’s streets were once named, not numbered, except for 30th through 50th Streets, which were once 1st through 20th Avenues. And even they had names before they became numbered avenues. The “original” numbering began at today’s 30th Street, which was 1st Avenue; why the numbering scheme began so far away from the East River is unknown.

Before the numbered avenues, though, they had names, as shown on the LIC Forgotten NY Street Necrology page. 1st Avenue was Lockwood Street, while 2nd Avenue was Debevoise Avenue, and so on. The original names were changed to numbers around 1900, and then to a different set of numbers in the 1920s. Queens is complicated.

Next week: 31st Street from Broadway to Ditmars Boulevard

Have I messed up bigly? kevinjudewalsh@gmail.com

11/5/16

2 comments

lived at 30- 59 31 street (gone now)

ps # 5 , jhs 126, bryant – on to bklyn and then binghamton, n.y.

nice job of capturing some to the old buildings and the character of the area.

thanks for your effort. love to see what grand ave looks like today.

Great article. It brought back memories of 60 years. However, the statement:

“The end of the 2nd Avenue El did bring some sunlight to the plaza, as half of the elevated complex was razed..”

is a bit misleading, since it implies the razing was done shortly after the 2nd Avenue El ceased operation. The northern half of Queensboro Plaza station wasn’t removed until the mid-1950s. For the rest of the 1940s, the tracks were used as follows: (I’m labeling them 1-4, south to north, and U and L for upper and lower levels):

L1; IRT trains from Flushing to Manhattan (as now)

U1: IRT trains from Manhattan to Flushing (as now)

L2: IRT from Ditmars Blvd. Astoria to Manhattan

U2: IRT from Manhattan to Astoria

L3: BMT to Manhattan

U3: BMT from Manhattan. Queensboro Plaza was the end of the line, and trains switched to L3

L4: BMT shuttle from and to Flushing

U4; BMT shuttle from and to Astoria

Astoria and Flushing line platforms were wooden, and made for IRT-width cars, so the BMT cars were IRT width. (Cars of this type are displayed in the New York City Transit Museum.) In 1949, BMT extended through service to Astoria, and the Astoria line platforms were literally sawed to accommodate the wider cars.Track usage at Queensboro Plaza became what it is today, but the (now surplus) northern 4 tracks and steelwork were not removed for years.